Artists: Juliette Blightman, Max Brand, Michaela Eichwald, Rochelle Goldberg, Yannic Joray, Veit Laurent Kurz, Benjamin Saurer, Ben Schumacher, Stefan Tcherepnin, Hanna Törnudd, Mark van Yetter, Miriam Visaczki

Exhibition title: Zur Rebschänke

Organised by: Veit Laurent Kurz

Venue: Weiss Falk, Basel, Switzerland

Date: June 14 – July 29, 2017

Photography: Gina Folly, all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Weiss Falk, Basel

In 1846, an issue of the British literary magazine Athenaeum featured a column signed off by Ambrose Merton (the nom de plume of William Thoms, 1803-1855). Written as a letter to the editor, the piece, called for a new term – ‘Folk-Lore’ – to describe the manners, customs, observances, superstitions and proverbs referred to, unto that point, as ‘popular antiquities’.

In the subsequent years, a group of antiquarians and enthusiasts would submit the collected oral tales to the periodical, establishing a regular exchange of lore for Britain’s foremost science, fine art and literature magazine. Not unlike today’s message boards, most of them were hiding behind ciphers or initials, only a few have been identified.

The Folk-Lore Column fought, in its own words, ‘against the extinction of fairies’. These gentlemen-correspondents paraphrased a panoply of local customs and superstitions before steam-engine, cotton mill or mail coach could exercise their detrimental business. They understood themselves as the very rivals to the Wise Men of Gotham.

In their view, one could not be satisfied by the beauty of a scenery without some savvy localism to evoke it. But at the time, the presentation of folk was blurred with mannerism and, instead of critical translation or retrieval, it became a literature of its own.

For his first seminal article, Thoms ardently referred to Jacob [James] Grimm’s extensive second edition of the Deutsche Mythologie (1835) – a book that failed the nationalistic agenda its title proposed. With the exception of a few Roman shreds, written records of a “German” mythology were scarce; Grimm’s account was essentially, an embellishment of orally passed-down tales combined with Christian-Icelandic and Scandinavian writings.

Along with Des Knaben Wunderhorn, (Brentano and Arnim, 1805-08) the Grimm Brother’s Kinder- und Hausmärchen (1812), is one of the first books concerned with oral folk tales and lyrics. Instead of empirical portrayals, the Heidelberger circle indulged their audience (children) with romantic expressions of the “peasant’s soul” – the trick was to claim the very same status for the romantic tale itself: an immaculate and innocent lore.

Athenaeum detailed the affairs of a disenchanted generation, one that started to dream up its very own local history. The fairies of this past – hidden people who refuse to come forward – are well aligned with the romantic reaction. In a last stand against the rational and secular, they resisted the religious imposition of virtue and vice and the bleak doctrines of an enlightened order. They were morally ambiguous, unpredictable. The most malevolent not incapable of bestowing gifts; the friendliest capable of bitter revenge. They were shunned for defective offspring and mouldy crops, quietly admired for their silent, overnight craft.

The early folklorists pleaded for a future with a “British” Grimm, but the Olden Time mythology went unnoticed. Eventually, their antiquarian interests gave way to a scientific pursuit.

Meanwhile, and with great diffusion, revivalists and eccentrics like William Beckford gave rise to a dark romanticism: the gothic novel. Rather than search for authentic primary sources to adapt into their narratives, these new romancers embraced an all-out false history. Feigned folklore – same as it ever was.

Their breeds are descendants of fairies evolved with experiments of rational science. Gothic horror pushed reason to its extreme and summoned irrational powers: frame-tale narrations, demonic alter egos, trap doors to Piranesian libertine-dungeons and a slew of unreliable sources provocating a reason sacrificed for the dawn of Promethean individualism.

It doesn’t help to abandon one hundred and fifty years of folklore because of its historical or figurative ambiguity. Rest assured, scores more are yet to conjure their own horror-versions of horror, while others dither over whether show titles should be in English or German.

Zur Rebschänke: a thirst quenching parlour to have a word with fanged folklore.

–Yannic Joray

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel

Veit Laurent Kurz, Untitled (Herba-4 series), 2016, Acrylic, coloured pencil, resin, ink, digital print on wood, 112 x 60 cm

Benjamin Saurer, Figure on Park-like Land (F), 2017, Cardboard and gouache on canvas, 60 x 46 cm

Yannic Joray, Weinpresse, 2017, Plaster, cardboard, wood, textiles, 60 x 45 x 80 cm

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel

Rochelle Goldberg, Nest, 2017, Feather, nylon, acrylic, lamp fossil, 160 x 180 x 100 cm

Rochelle Goldberg, Nest, 2017, Feather, nylon, acrylic, lamp fossil, 160 x 180 x 100 cm

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel

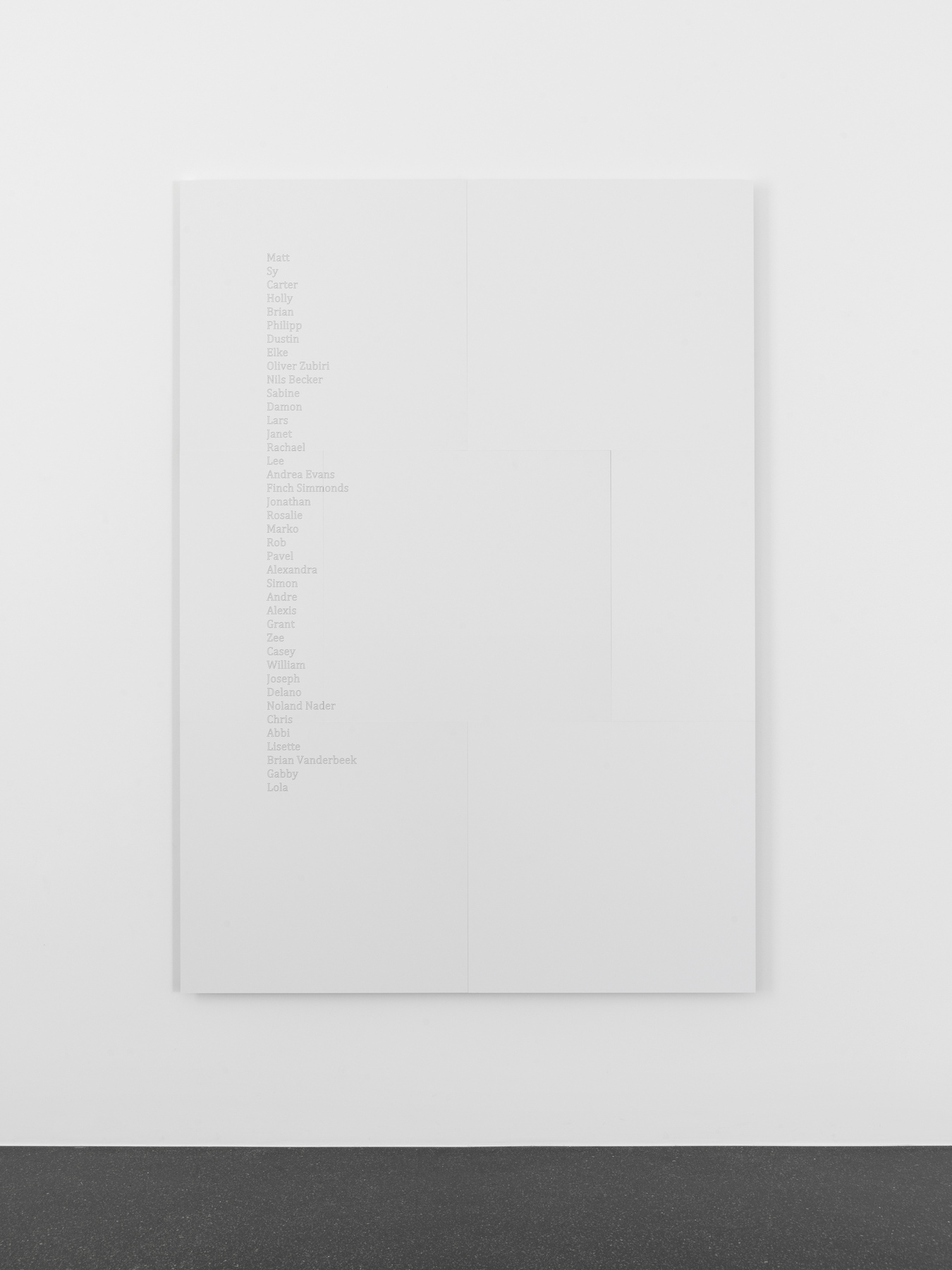

Juliette Blightman, Day 149, 2016, Pencil on canvas, 70 x 50 cm

Benjamin Saurer, Figure on Park-like Land (I), 2017, Cardboard and gouache on canvas, 60 x 46 cm

Hanna Törnudd, Musk Ox, 2016, Plaster, litter, acrylic, wood, metal, 120 x 120 x 60 cm

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel

Juliette Blightman, I Want to Live in the Country (And Other Romances), 2016, Pencil, gouache and acrylic on canvas, 40 x 50 cm

Stefan Tcherepnin, The Crying Machine, 2017, Crying Machine, 32 x 14 x 14 cm

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel

Veit Laurent Kurz, Untitled, 2015, Acrylic, coloured pencil, resin, ink, digital print on wood, 56 x 80 cm

Veit Laurent Kurz, Untitled, 2015, Acrylic, coloured pencil, resin, ink, digital print on wood, 56 x 80 cm

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel

Miriam Visaczki, Perl, 2017, Felt, wood, 60 x 80 cm

Ben Schumacher, (M.d.m.m.d.k.i.d.) Mother, The Man With The Coke is Here, 2016, Aluminium, corduroy, cotton, pins, foam, vinyl, hardware, inkjet on paper, frames, acrylic, 178 x 80 x 33 cm

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel

Veit Laurent Kurz, Herba-4 Scepter #7 (Herba-4-Series), 2014-2015, Wood, acrylic, gel wax, plastic flowers, plastic tube, electrical parts, 120 x 15 x 15 cm

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel

Stefan Tcherepnin, Shrooms, 2017, Paint on wood, Each: 6 x 4 x 4 cm

Max Brand, Untitled, 2017, Acrylic paint, chalk, crayon, water color, ink, marker, fine liner, fabric on canvas, 180 x 140 cm

Stefan Tcherepnin, Spatula, 2017, Steel, plastic and leather, 60 x 8 cm

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel

Juliette Blightman, Day 193, 2016, Pencil and gouache on canvas, 70 x 50 cm

Stefan Tcherepnin, Night Light, 2017, Stain glass lamp, 34 x 27 x 6 cm

Max Brand, Untitled, 2017, Marker, oil pastell and crayon on paper, 58 x 40 cm

Mark Van Yetter, Untitled, 2015, Oil on paper, 74 x 54 cm

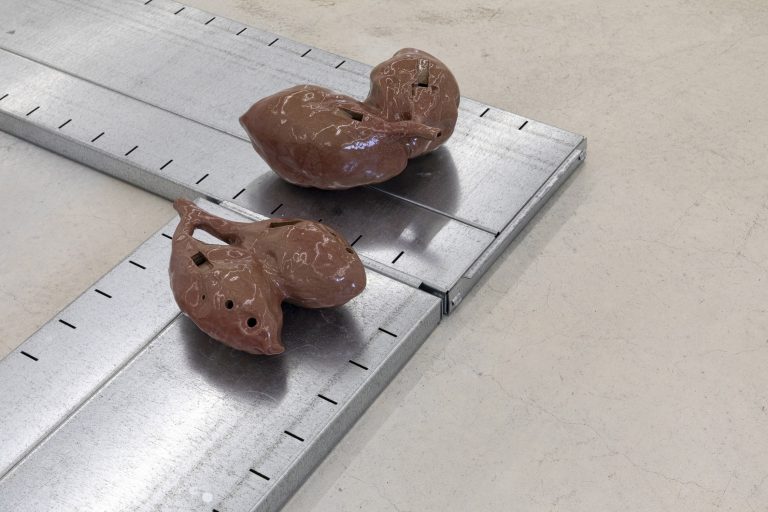

Michaela Eichwald, Ohne Titel, 2008, Epoxy resin, ceramic, wire brush, tea bags, 30 x 30 x 20 cm

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel

Benjamin Saurer, Shape of You, 2017, Cardboard and gouache on canvas, 45 x 36 cm

Benjamin Saurer, Transhuman Housewife, 2017, Cardboard and gouache on canvas, 42 x 33 cm

Benjamin Saurer, Pied Mystique, 2017, Cardboard and gouache on canvas, 45 x 36 cm

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel

Veit Laurent Kurz, Untitled (Herba-4 series), 2016, Acrylic, coloured pencil, resin, ink, digital print on wood, 45 x 60 cm

Veit Laurent Kurz, Untitled (Herba-4 series), 2016, Acrylic, coloured pencil, resin, ink, digital print on wood, 36 x 49 cm

Mark Van Yetter, Untitled, 2015, Oil on paper, 74 x 54 cm

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel

Ben Schumacher, The Album as a Short History of Mental Health, 2017, UV print on oil on canvas, 100 x 140 cm

Zur Rebschänke, 2017, exhibition view, Weiss Falk, Basel