Artists: Sol Calero, Susi Gelb, Anna Schachinger, Sara Sadik

Exhibition title: Various Others

Nir Altman hosting: Crévecoeur, Paris und Sophie Tappeiner, Vienna

Venue: Nir Altman, Munich, Germany

Date: September 10 – October 30, 2021

Photography: Dirk Tacke / all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Nir Altman, Munich

Working in a small college art collection in England, one day the curator came to tell me that she had discovered a lost painting behind a bookshelf in the library. The painting depicted a woman from behind, sitting at an easel, painting. It belonged to a genre in which men once painted domestic or intimate scenes, mostly in the industrial North of England. I was especially interested in this woman’s painting, the one in the image, which had not been retrieved with the curator’s discovery. The painting woman and her canvas were still left to dwell in this picture of domesticity, while the dusty frame in which they were confined could now demarcate a work of art once more.

It’s perhaps a strange anecdote to introduce the exhibition of Sol Calero, Susi Gelb, Anna Schachinger, and Sara Sadik for Various Others. However, I am reminded of this painting, the painting within the painting, the painted woman and the painting woman whenever I observe differently gendered constructions of domesticity, sociality and intimacy and their depictions across genres in the arts. In the collaboration with Galerie Crèvecœur, Paris and Sophie Tappeiner, Vienna, NIR ALTMAN brings together four artists whose highly personal processes produce various “movements of life”, as Carla Lonzi once put it: “to develop a creative condition in people, to live life in a creative way, not in obedience with the models that society proposes over and over.” That is to say, their works each reorientate the traditional axes of genre – in all of the word’s overlapping meanings.

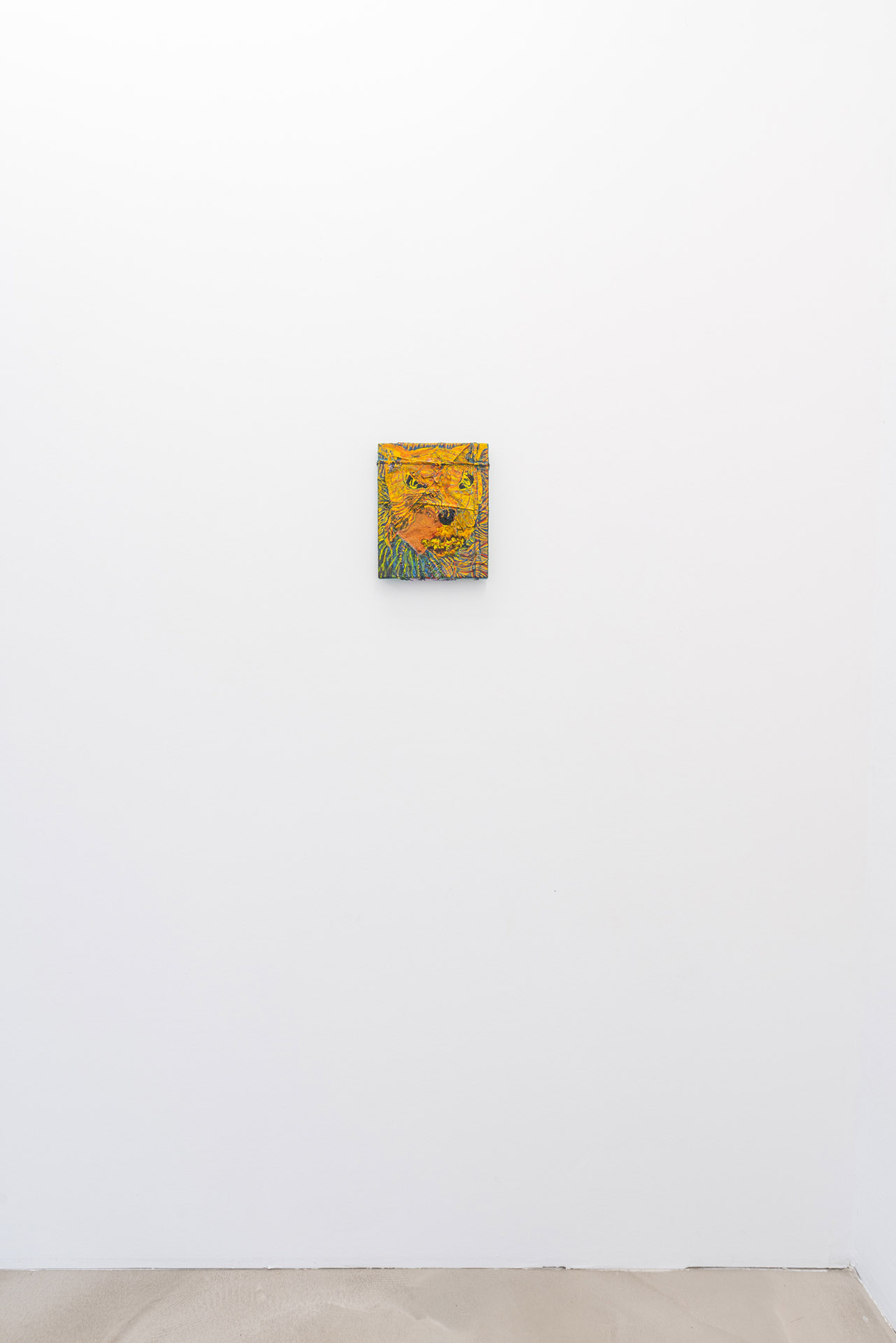

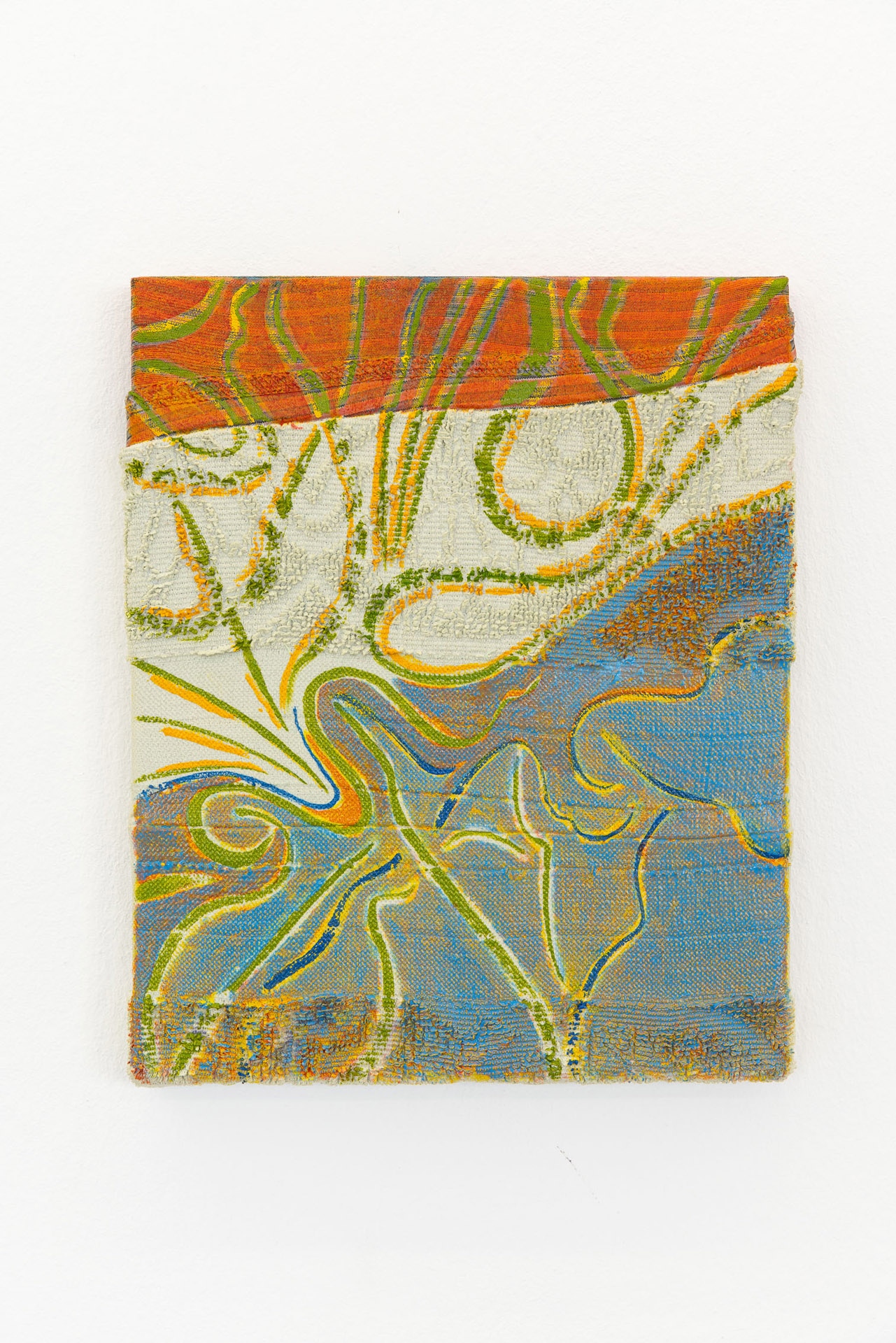

Rather than routine, which always seemed to me to neutralise the transformative power of steadfast repetition, the notion of iteration accommodates the incremental changes that take place when we perform the same gestures over and over again. The gradual accumulation of meaning in the expanding collection of fabrics, for instance, is implicit within Anna Schachinger’s paintings, becoming more apparent as the different materials enter into dialogues, contradicting and celebrating one another as they act as the picture planes of her paintings. The figurative elements that emerge – the lion, the kitten – do so with the same inevitability as the expressive gestures that appear in lines and bleeding pigments. Working diligently with the frayed edges and the slackness of certain fabrics, Schachinger superimposes an absurd rationality onto the miscellany of errant surfaces, creating objects whose components do not shy away from their origins as “stuff” while taking up a revalorised role at the same time.

The iterative qualities of collecting objects, putting them on display over and over again, can also be observed in Sol Calero’s paintings for the exhibition, transposed from another installation where they formed part of an imagined restaurant setting. I am in awe of the gastronomy industry and its commitment to a certain scenery, which makes it possible for us to take up a temporary stance set apart from responsibility, a sociality uninhibited by pragmatism – aside from the small matter of the bill, of course. These paintings, now framed and hanging on the walls, seem to extract the imagery we are accustomed to seeing as backdrops to our outings. Their recontextualisation in this exhibition is bittersweet, insofar as it also gestures towards the time in which restaurants have been restricted in their activities, due to the pandemic. The dreams of a slumbering restaurant unfold in sketches made as quick as thoughts, which have fled those deserted spaces to seek their viewers in galleries.

Sara Sadik’s video Khtobtogone gives an intimate account of Zine, a working-class member of the Maghrebi diaspora in France. The narrative, inspired by stories from Ahmed Ra’ad Al Hamid and Brian Chiappeta, sees Zine faced with the agonising and contradictory expectations that shape his future. Sadik’s portrayal of Zine is attentive to the tensions exerted by racial, class-based and gendered norms, and how these norms differ contextually. The love that Zine feels for his male friends is incompatible with the love he feels for the woman Bulma, although the words he uses to describe his feelings are not dissimilar in each instance. Created using Grand Theft Auto V, the graphics have an impersonal quality that makes Zine’s vulnerability seem transferable to other identifications, in spite of the specificity of the language, the cultural markers and his personal relationships. The slight glitches in the imagery skip over the hypermasculine behaviour and machoistic violence of typical GTA narratives, as Zine describes nights weeping over heartbreak and his imperative to be better, wanting to be seen by others in a positive light.

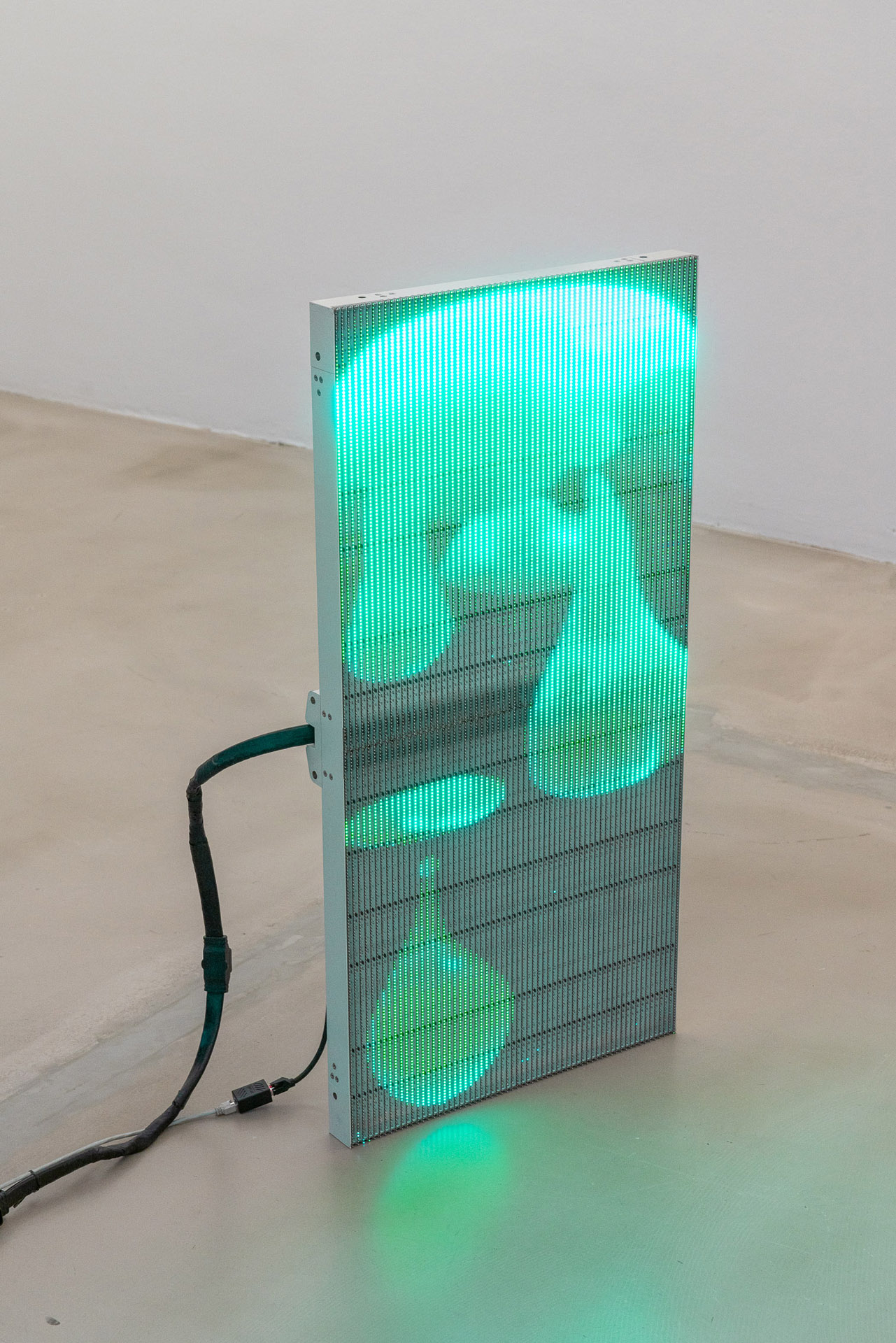

Recounting how she came to art criticism, the Italian feminist Carla Lonzi says, “I arrived at art when, having passed through my religious experience, I found in the artistic experience an activity that didn’t require belief … but satisfied an analogous need.” The ambiguous relation between art and belief seems to animate Susi Gelb’s works for the exhibition, especially in terms of their alchemical references. If belief is not satisfied by art, what is the analogous need that is? Perhaps the suspension of disbelief. The notion that “reality is a fake” seems to me a good prerequisite for making one’s own magic. Casting liquid shapes that float before photographic seascapes, Gelb creates fluid bodies that appear to have emerged from beyond the horizon. A holographic video sculpture observes the hypnotic movements of floating lava, flowing continuously and creating new forms. The schema of visual references in Susi Gelb’s works is permeated with liquids; the inevitability of change encapsulated in the image of waves invokes the sublime quality of repetition, its capacity for creation and destruction – regardless of what we believe.

In writing about these artists’ respective positions, I cannot help but feel as though I have taken up the role of the man painting the woman, quite literally behind her back. Carla Lonzi, who eventually rejected art criticism in favour of more explicitly political feminist activism, bemoaned critics who were “phony” in their relation to art: he or she “trespasses onto things that humanity has toiled at much more and much more deeply, and says his [sic] piece and then he [sic] returns to his [sic] small-minded things.” The more I write, the greater the danger appears that she was right. It is only when the repetition of a certain praxis folds back on itself that we might see the scope for some reinterpretation the second, third or fortieth time around. It is thus that this exhibition reveals the importance of living life in a creative way: while repeating, maintaining and enduring, always allowing oneself to be surprised by the things that happen today, purely because they happened yesterday, and they might well happen tomorrow, too.

Text by Miriam Stoney