Artist: Tom Evans

Exhibition title: Eye and Mouth

Venue: Freddy, New York, US

Date: June 10 – July 1, 2017

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Freddy

This essay first appeared in a catalogue published by The New Museum for its exhibition, New Work/New York, which was on view January 30th – March 25th, 1982. New Work/New York was curated by Lynn Gumpert and Ned Rifkin. It featured work by Tom Butter, Tom Evans, John Fekner, Judith Hudson, Peter Julian, and Cheryl Laemmle.

Three years ago, Tom Evans was a painter in his mid-thirties who was affiliated with a well-known New York gallery. An artist from Minnesota who had lived in Manhattan for less than ten years, Evans had, by most standards, begun to “make it.” He was becoming known as a painter of finely brushed color field abstractions, each controlled stroke a luminous tessera woven into a surface of radiant color. There was, however, one problem. “I felt I had exhausted the direction. It became tedious; I was getting bored. I realized that, while the paintings were definitely changing, they were not getting better,” Evans confesses. “They lost intensity and were becoming too introverted.”

Even for the artists of modest reputation, the style they evolve and with which they are identified can become an albatross. Those who sell their work are faced with additional problems of esthetic renewal in the face of an already commercially successful look or technique. While this is not necessarily confining for all artists, Evans was stymied by it.

He made one important change immediately. He put away his sable brushes and broke out the palette knife. “The new paintings evolved very fast. At a certain point there was a clear suggestion of images forming and I thought, ‘Why not carry that out to its logical conclusion?’” Evans realized that he had been harboring grave doubts about abstract painting for some time. “They don’t have the force that they once had. People are tired of them,” Evans claims. “I began to ask myself, ‘If I were the only person painting, what would I do?’ It always disturbed me that it required a cultivated or conditioned eye to see these [earlier] paintings.” At about this time, it occurred to Evans that had he placed one of his older paintings on the sidewalk, few passers-by would take notice. He vowed to create paintings people would be forced to respond to–positively or negatively–in a decisive way.

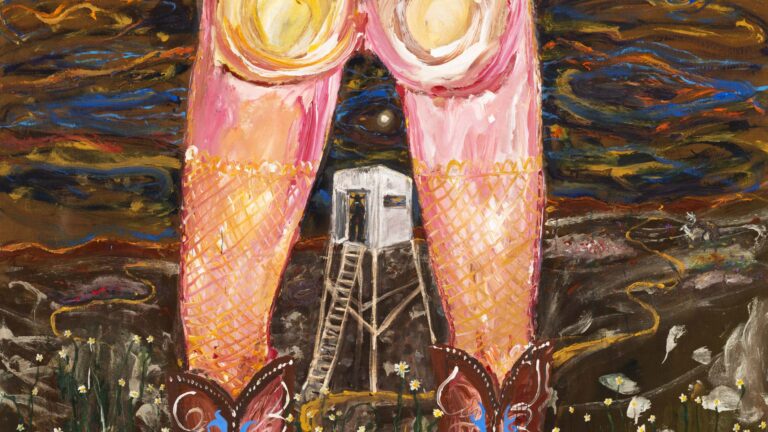

Asked if there is anything that reveals his background, having been born, raised, and educated in Minneapolis-St. Paul, Evans replied, “I don’t shout.” While it is true that he is soft-spoken (albeit out-spoken), Evans allows his new paintings to do his yelling for him. Since he left his gallery and the quiet abstractions of a few years ago, his new work is clamorous, aggressive, and eccentrically image-based. Seething with gargoyles and other monstrous creatures with bulging eyes and serpentine tongues, muscular lips, and jack-o’-lantern teeth, Evans’ paintings have been radically transformed.

These powerful paintings are curiously ambivalent. They pulse and rumble with basstone thunder. The beings that populate the images are ominous, menacing, and threatening at times, yet they are sumptuously painted and somewhat comical with their robust, toothy grins, and insatiable appetites. Their forceful drive is deliberate and undeniable. Whereas Evans’ earlier works were passive and serene, aloofly drawing the viewer into the comfort of orchestrated repetition and chromatic resonance, the new work is brash, provocative, and raucous. The tumult of these unleashed dynamic forms and bold range and combinations of colors dominate the viewer, actively seizing hold of our attention and bruising more refined retinal sensibilities.

Nevertheless, these are masterfully composed and crafted paintings. The tactile richness of the thickly applied paint, along with the undulations of the forms and sheer intensity of Evans’ palette, attracts us as much as the imagery may repel us. “I think about the images for quite a while before I paint them,” states Evans. He works out the composition, often in completed drawings and has a definite idea of the colors he plans to deploy. Though these will occasionally change as the painting process ensues, the adjustments he makes are not major ones.

Composition is crucial to the impact of the works. Cropping is used to enhance the imagery and to evoke a giant scale for the creatures. “I definitely think of them as larger than life,” the artist explains. We never see an entire monster, and most often they are in the process of benignly devouring each other so that the viewer never knows where one begins and another ends. They exist in a non-specific place without references to gravity. At times it is difficult to distinguish up and down since there is no ground plane and the eyes, mouths, and tongues converge from many directions. The pervasive disorientation is intended. Evans insists, “Antaeus always wins. The idea that gravity will prevail is inevitable. . .Only in our dreams and myths can we overturn this.”

These beings do, indeed, have an unspecified mythic quality. Though Evans reads mythological literature and is particularly fond of the Babylonian myths, he believes that these references are not directly translated into the paintings. They are nonliterary in character. “These images could only have been made by a painter. It’s extremely difficult to describe in words something people have not already seen,” Evans claims.

Various visual sources for Evans’ imagery come to mind. Brazilian carnivale, Mardi Gras masks, Mexican murals, doodles, low-rider auto paintings, Chinese dragons, African sculpture, some of Francisco de Goya’s darker paintings, as well as the apocalyptic visions of Hieronymous Bosch and Pieter Bruegel. Indeed, Evans acknowledges that, when he was younger, Bosch was his favorite artist. However, for him, these paintings no longer have the presence that he seeks in his own current work.

Whatever sources can be traced to Evans’ new work, they resound as thoroughly original paintings of integrity, arresting and compelling in their uncompromising vitality. There is a heroic element present, not only in the imagery, but also in Evans’ determination to throw off self-imposed limitations of style in order to forge a consistent vision which is extremely personal yet exceedingly accessible.

–Ned Rifkin

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth, 2017, installation view, Freddy, New York

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth, 2017, installation view, Freddy, New York

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth, 2017, installation view, Freddy, New York

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth, 2017, installation view, Freddy, New York

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth, 2017, installation view, Freddy, New York

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth, 2017, installation view, Freddy, New York

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth, 2017, installation view, Freddy, New York

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth, 2017, installation view, Freddy, New York

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth, 2017, installation view, Freddy, New York

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth 1, 1980, Pencil on paper, 8 x 9.5 inches

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth 2, 1980, Colored pencil on paper, 8 x 9.5 inches

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth 3, 1980, Colored pencil on paper, 8 x 9.5 inches

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth 4, 1980, Colored pencil on paper, 7.5 x 11 inches

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth 5, 1980, Pencil on paper, 6.5 x 9 inches

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth 6, 1980, Colored pencil on paper, 8 x 9.5 inches

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth 7, 1980, Colored pencil on paper, 8 x 9.5 inches

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth 8, 1982, Colored pencil on paper, 8 x 9.5 inches

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth 9, 1980, Colored pencil on paper, 7.5 x 9 inches

Tom Evans, Eye and Mouth 10, 1982, Colored pencil on paper, 8 x 9.5 inches

Tom Evans, Source, 1981, Oil on canvas, 60 x 72 inches

Tom Evans, Thrust, 1981, Oil on canvas, 60 x 72 inches

Tom Evans, March, 1981, Oil on canvas, 44.5 x 60 inches