Artists: Athanasios Argianas, Zbyněk Baladrán, Thomas Bayrle, James Benning, Bureau d’études, Steven Claydon, Tyler Coburn, Philippe Decrauzat & Alan Licht, Harry Dodge, Juan Downey, Cécile B. Evans, Judith Fegerl, Melanie Gilligan, Peter Halley, Channa Horwitz, Geumhyung Jeong, David Jourdan, Barbara Kapusta, Konrad Klapheck, Běla Kolářová, Nick Laessing, Mark Leckey, Tobias Madison & Emanuel Rossetti, Benoît Maire, Mark Manders, Daria Martin, Shawn Maximo, Régis Mayot, Wesley Meuris, Gerald Nestler, Henrik Olesen, Julien Prévieux, Magali Reus

Exhibition title: The Promise of Total Automation

Curated by: Anne Faucheret

Venue: Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna, Austria

Date: March 11 – May 29, 2016

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Kunsthalle Wien

Note: Exhibition booklet can be found here

What shall we do next? That’s what Julien Prévieux calls his video piece that demonstrates the range of gestures that modern, technological gadgets demand. The video shows a group of male and female dancers engaging in movements used to handle smartphones and tablet computers. The gestures they present were the subjects of patents filed by companies producing these devices. But who owns the movement of the hand once it is patented? Are people still users of these devices or are they already components of them?

Transcending our general fascination with technology, The Promise of Total Automation explores which kind of hopes and fears, utopias and dystopias, arise alongside the notion of automation. This debate is tremendously current, even though at present the issues raised are mostly discussed in the domains of technology and the natural and social sciences. Kunsthalle Wien injects itself into this debate and adds to it a multiplicity of voices from the field of contemporary art.

The promise of total automation was the battle cry of Fordism. The optimization and automation of the processes of production had an impact not only on the global economy, but also signaled the arrival of massive socio-political change. Automation brought forth machines and devices that were not only suitable for producing and circulating commercial goods, but also contributed to making communication and information global.

The transfer of labor from people to machines constituted an important component of civilization’s progress as well as of social distresses during the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Digitalization then launched the definitive dematerialization of the physical world, consolidating the idea of domination of mankind over nature and the whole ecosystem, consecrating the human use of human (and non-human) beings. The most recent wave of automation, which is based on the communication between machines and our reactions to this phenomenon, demonstrates once again how variously humans understand the promise that accompanies the notion of automation. While technology has brought about huge improvements to labor and standards of living, the ruling economic and political system of financial capitalism has benefitted the most. Functioning as an abstract machine in this technological system, technology is instrumentalised as a way to increase benefits and therefore to model perfect liberal subjects living in forecasted scenarios of consumption and entertainment. Other practices and architectures are taking form.

Five objects in the show function as historical anchors in the exhibition and in the history of automation: A programmable Jacquard-loom is representative of the Industrial Revolution and the far-reaching social and economic changes it brought about, as well as representing the origins of the binary code and the separation between hardware and software. An arithmometer, once used to automate mathematical calculations, is recognized and included as a precursor of the modern computer. A Morse code apparatus, which revolutionized communication; a cybernetic model from 1956 (an experimental device trying to define an algorithm forecasting orientation in space) and finally a computer as such represent the final three of the technical devices which are presented among artworks. They find a new possible mode of existence within a broader cultural, anthropological and aesthetical history.

These days, machines and devices have their own means and ways to process information. They communicate with one another and with their environment without a human agent. This autonomy as well as the disappearance of their technologically defined appearance moves them into the vicinity of ritual artifact bearing their own meaning, and – whether people intended them to or not – seem to live a life of their own.

Daria Martin’s film Soft Materials conveys the relationship between humans and machines as an act of mutual getting-to-know-one-another by touch. On the part of the machine, there are no programmed actions; instead, what occurs is a learning process launched by means of interactivity.

In his work Kleiner koreanischer Wiper, Thomas Bayrle explores the aesthetics of mechanical production and lends it a certain aura. His machine-fragments feature running engines as metaphorical stand-ins for the rhythm of life characterizing modern large-scale societies – all the while revealing our fascination with technology-driven, functional aesthetics.

It was during the mid-60s, that Běla Kolářová engaged with her surrounding technical objects, without reducing them to their function but making them the vibrant matter of her work. In Alphabet hooks, eyelets, chains, steel tubing, or hex keys are configured as a mysterious alphabet, reinscribed in the world of significations.

Magali Reus’ padlocks sculptures from the Leaves series, in turn, play with the aura of technology in that they remind us of complex technological apparatuses. Equipped with sprockets, metal pipes and valves, they seem to measure and process data while the actual determination of the object lies in the imagination of the beholder. Unlike technological devices, they exhibit their interiors and the precise way they are built as a stratification of various materials and textures. Still, these sculptures thus remain just as fascinating as incomprehensible.

Peter Halley hints at abstract, technological systems. His paintings seem to suggest simplified versions of cybernetic models and technological processes but at the same time remain autonomous abstractions. Working on large-format canvasses and using fluorescent colors, he creates geometrical compositions of cells and network structures, at the same time psychedelic and dystopian. In constant connection, the individual is still isolated.

Contemporary human and non-human existence is dependent on technology. This is enriching as well as threatening. Resistance to technologized society and the questionable nature of its promises takes form in James Benning’s video Stemple Pass in which he projects four landscape shots lasting 30 minutes each. Pictured are the changing seasons around the log cabin where Unabomber Ted Kaczynski took refuge in the woods of Montana. The philosophy informing Kaczynski’s terrorist deeds lies in his rejection of a specific form of technological progress which serves to permanently expand the influence and regulatory control exercised by social elites over the individual.

Tyler Coburn’s 3D print piece Sabots is using another symbol of resistance against automated labor. As such, Coburn references the wooden footwear (sabots) worn by French laborers who, apocryphally, saw sabotage – for instance, throwing shoes into the machine, thereby causing its destruction – as a legitimate means of resistance against the automation of production threatening human labor.

In The Promise of Total Automation, artists examine technology in its complexity. They point out our fascination with technology as well as the rational and irrational fears and expectations that arise alongside automation. Production machines, technological devices, videos, pictures, sculptures and installations are set up to relate to one another in the exhibition space. In the interplay of all the objects, the exhibition itself becomes a narrating machine that reports on an archaeology of the digital age and the utopias of a technological future.

The Promise of Total Automation, Kunsthalle Wien 2016, Photo: Stephan Wyckoff

The Promise of Total Automation, Kunsthalle Wien 2016, Photo: Stephan Wyckoff

Magali Reus, Leaves (Amber Line, May); Leaves (Harp January), 2015, Courtesy the artist, The Approach, London and Rubell Family Collection

The Promise of Total Automation, Kunsthalle Wien 2016, Photo: Stephan Wyckoff

The Promise of Total Automation, Kunsthalle Wien 2016, Photo: Stephan Wyckoff

Melanie Gilligan, The Common Sense, 2015, Courtesy the artist and Galerie Max Mayer, Düsseldorf

The Promise of Total Automation, Kunsthalle Wien 2016, Photo: Stephan Wyckoff

Peter Halley, Electric Slide, 2014, Courtesy Jablonka Maruani Mercier Gallery, Brussels

Athanasios Argianas, Silence Breakers, Silence Shapers (Aberrations on Percussion) No. 9, 2015, Courtesy the artist and Aanant & Zoo, Berlin

The Promise of Total Automation, Kunsthalle Wien 2016, Photo: Stephan Wyckoff

Harry Dodge, fuck me/who’s sorry now; love fuzz/many mr. strange (consent-not-to-be-a-single-being series), 2015, Courtesy the artist and Beth Rudin DeWoody

Wesley Meuris, Case R-Y3.001, 2016, Courtesy Annie Gentils Gallery, Antwerp and Galerie Jérôme Poggi, Paris

Steven Claydon, Orion (prepared spinet), 2012, Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London

The Promise of Total Automation, Kunsthalle Wien 2016, Photo: Stephan Wyckoff

Athanasios Argianas, Silence Breakers, Silence Shapers (Aberrations on Percussion), No. 9 (Detail), 2015

Song Machine No.7 (Detail), 2007, Courtesy the artist, Aanant & Zoo, Berlin and Daman Sanders; Barbara Kapusta, Die Klammer und das O, 2016, Courtesy the artist

The Promise of Total Automation, Kunsthalle Wien 2016, Photo: Stephan Wyckoff

Harry Dodge, fuck me/who’s sorry now; love fuzz/many mr. strange (consent-not-to-be-a-single-being series), 2015, Courtesy the artist and Beth Rudin DeWoody

The Promise of Total Automation, Kunsthalle Wien 2016, Photo: David Avazzadeh

Mark Manders, Finished Sentence (August 2010), 2010, Courtesy the artist, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Steven Claydon, Antenna, 2015, Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London

Konrad Klapheck, Der Chef, 1965, Courtesy Collection of the Museum Kunstpalast Collection, Dusseldorf, © VG Bild Kunst Bonn / BILDRECHT GmbH Wien

Peter Halley, Total Recall, 1990, Private Collection, Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Běla Kolářová, Alphabet, 1964, Courtesy Kontakt. Die Kunstsammlung der Erste Group und ERSTE Stiftung

Daria Martin, Soft Materials, 2004, Filmstill, © Daria Martin, Courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Cécile B. Evans, How Happy a Thing Can Be, 2014, Videostill, © Cécile B. Evans, Courtesy Radar/LUA, Wysing Arts Center, Cambridge

Richard Eier, Kybernetisches Modell Eier: Die Maus im Labyrinth, 1956, Courtesy: Technisches Museum, Vienna

Konrad Klapheck, Der Chef, 1965, © VG Bild Kunst Bonn / BILDRECHT GmbH Wien, Photo: © Museum Kunstpalast – ARTOTHEK

Wesley Meuris, Biotechnology & Genetic Engineering, 2014, Courtesy the artist and Annie Gentils Gallery

Régis Mayot, JEANNE & CIE, 2015, Courtesy the artist and CIAV Centre International d’Art verrier – Meisenthal France, Photo: Guy Rebmeister

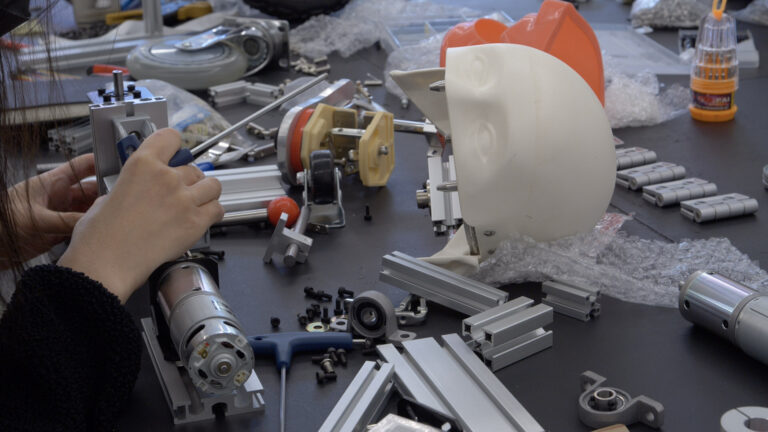

Geumhyung Jeong, CPR Practice, 2015, © Geumhyung Jeong, supported by Arts Council Korea, Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture, Akademie Schloss Solitude (Stuttgart/Germany), Co-produced by SPIEL ART FESTIVAL Munich, 2013, Photo: Jiwoong Nam

Henrik Olesen, how do i make myself a body? (Detail), 2008-2016, © Henrik Olesen, Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York

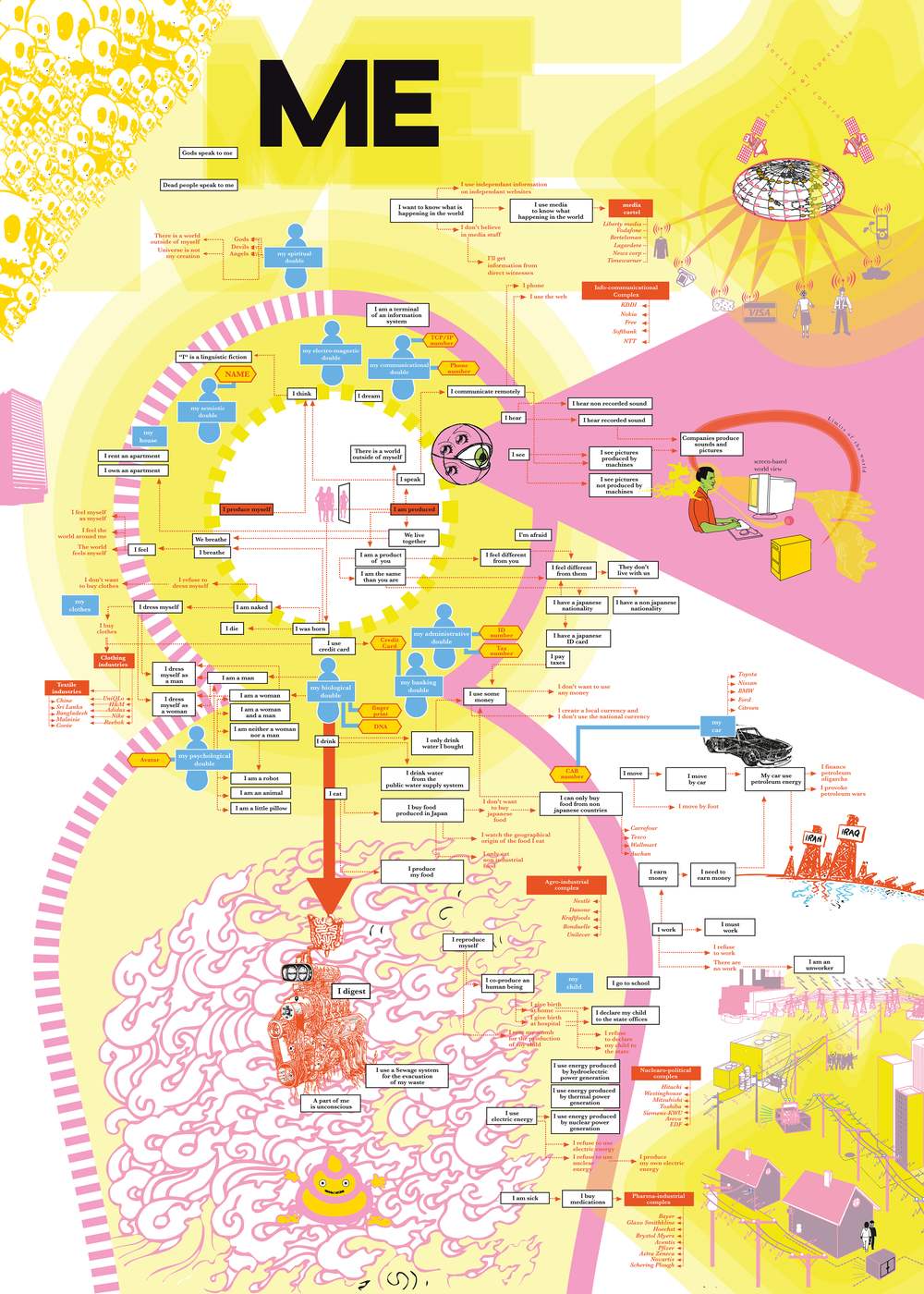

Bureau d’études, ME, 2013, © Léonore Bonaccini and Xavier Fourt