Artists: Elina Alekseeva, Johanna Bruckner, Penelope Cain, Wim van Egmond, Lizan Freijsen, Escuela de Garaje, Aslı Hatipoğlu, Marit Mihklepp, Natalia Sorzano

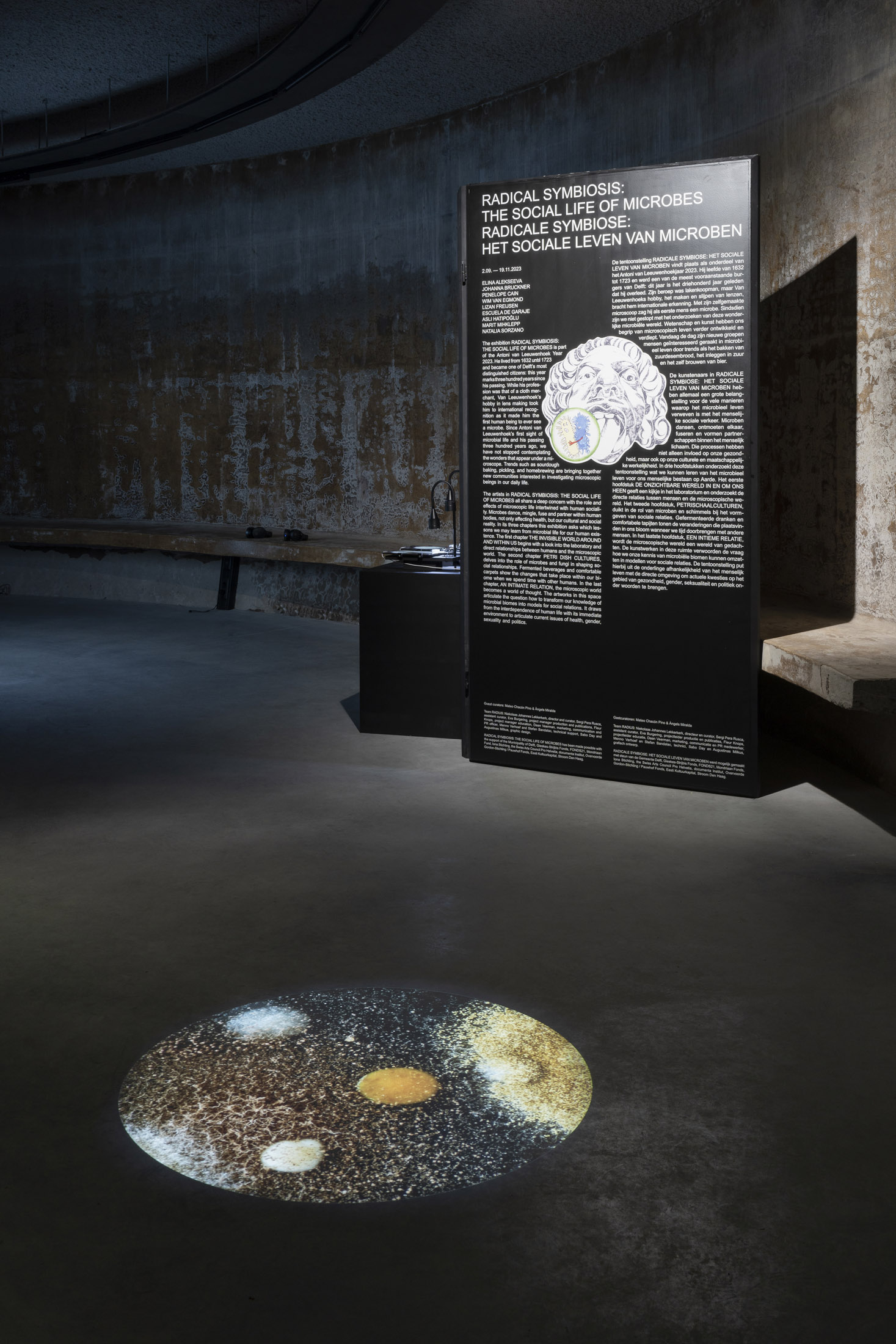

Exhibition title: Radical Symbiosis: The Social Life of Microbes

Curated by: Mateo Chacón Pino & Àngels Miralda

Venue: RADIUS Center for Contemporary Art and Ecology, Delft, The Netherlands

Date: September 2 – November 19, 2023

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and RADIUS Center for Contemporary Art and Ecology

Note: Exhibition’s booklet is available here

The exhibition RADICAL SYMBIOSIS: THE SOCIAL LIFE OF MICROBES takes place as part of the Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Year 2023. This Delft researcher, city official and cloth merchant lived from 1632 to 1723 and is regarded as a pioneer in the study of microbial life and microscopic structures and processes. Since Antoni van Leeuwenhoek’s first sight of microbial life and his passing three hundred years ago, we have not stopped contemplating the wonders that appear under a microscope. Ever since science and art have developed further and deepened our understanding of microscopic life. After the years of pandemic and the trends of sourdough bread and home-brewing, it is time to look at the imaginaries that inform our relationship to the microbial world.

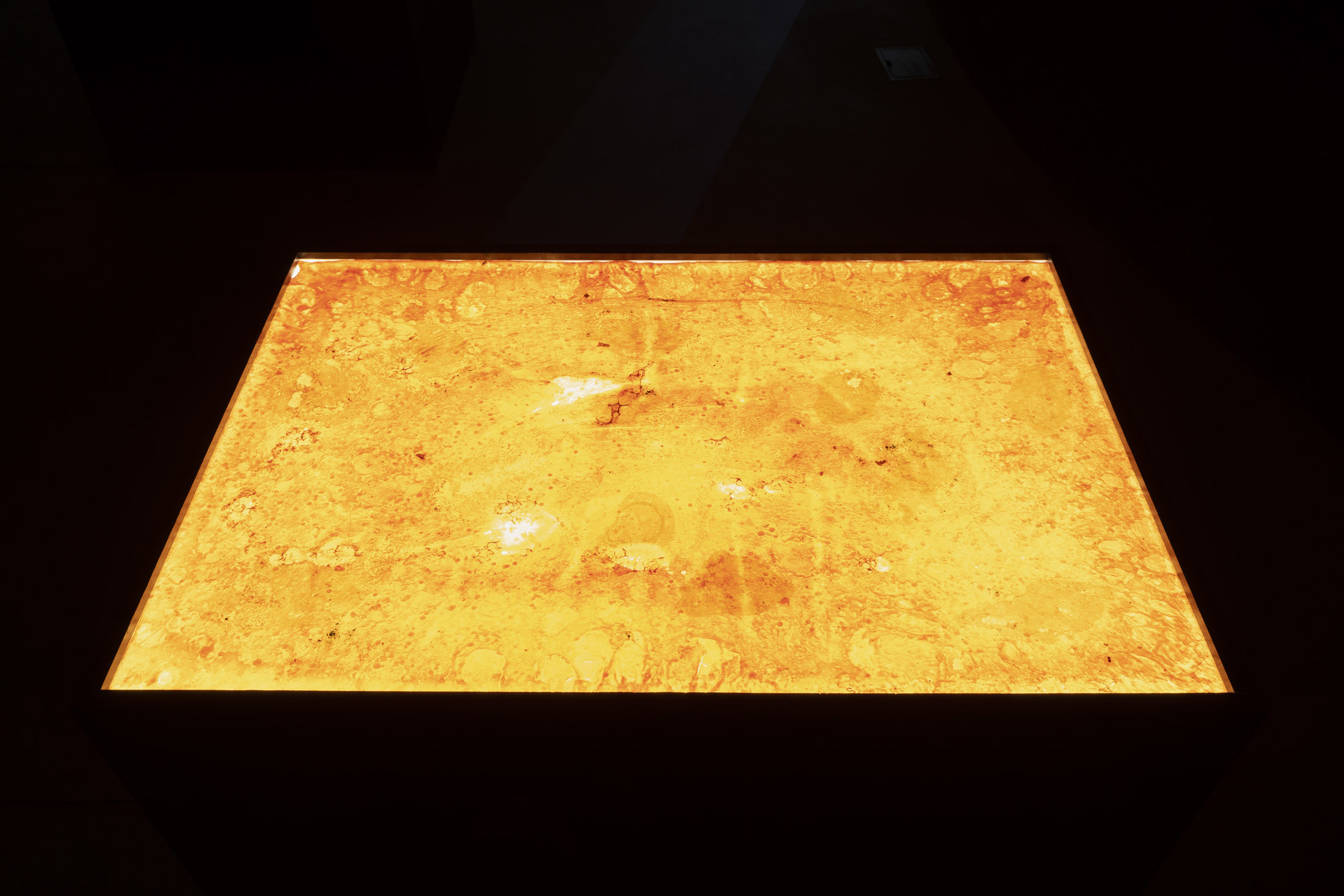

This exhibition gathers a group of artists who engage with bacteria, yeasts and microbes. In the three chapters THE INVISIBLE WORLD AROUND AND WITHIN US, PETRI DISH CULTURES and AN INTIMATE RELATION this exhibition asks which lessons we may learn from microbial life for our human existence on earth. The first chapter begins with a look into the laboratory and direct relationships between humans and the microscopic world. Most of the time, these perspectives are built upon scientific findings and the production of spectacular images. The second chapter, PETRI DISH CULTURES, invites the audience to interact more closely with the exhibited works and communal artistic practices. This space delves into the role of microbes and fungi in shaping social relationships. Fermented beverages and comfortable carpets show the changes that take place within our biome when we spend time with other humans. In the last chapter, AN INTIMATE RELATION, the microscopic world becomes a world of thought. The artworks in this space articulate the question how to transform our knowledge of microbial biomes into models for social relations. It draws from the interdependence of human life with its immediate environment to articulate current issues of health, gender, sexuality and politics.

Imagine how wondrous hundreds of tiny moving beings must have appeared to a perplexed Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, when he first spotted microscopic life through his self-made, handcrafted lens. On the 7th of September 1674 he wrote a letter in which he described a sample of a white layer floating on the lake that we now recognise as a bloom of cyanobacteria. In this first glimpse, he spotted various different lifeforms and continued to find not just some new animalcula, but thousands upon thousands. He wrote many such letters to peers from the academic field, detailing the unusual shapes and movements of various different microbes which he observed, the tiniest of which were over a thousand times smaller than the cheese-mites he had previously been able to observe with his naked eye.

Van Leeuwenhoek’s microscopic world confronted our scientific understanding with fundamentally different dimensions of life and forms of coexistence and cohabitation, compared to what was previously known to be the relationship between humans and their world. In this microscopic universe, life develops different strategies for survival. What van Leeuwenhoek described in his letters were winding and turning bodies of microbes pivoting through liquids with each other in complex interrelations. These microbes were everywhere, and human beings had never been able to see them before. He started to take samples from his own body, from his teeth and gums which resulted in the realisation that even our bodies are filled with these tiny creatures. Not only was his body brimming with microbes, but that of his wife, daughter, and every inhabitant of Delft as well.

This astonishing discovery took nearly a century for scientists to develop into the field of microscopy, and even more for microbiology to fully develop into a scientific discipline. For many years, microbes were believed to cause only disease and aggressive methods were applied to remove them from all surfaces and from within our own bodies, this was later shown to be incorrect since our microbiota are an important part of our digestive and health system. Today, we are still discovering the abilities and consequences of the microbial worlds that live within us, affecting our health and culture.

Trends such as sourdough baking, pickling, and home-brewing are bringing together new communities interested in investigating microscopic beings in our daily life. Scientific analysis is one way to approach microbes, but artists bring a different knowledge of microbial sociality. The artists in this exhibition all share a deep concern with the role and effects of microscopic life intertwined with human sociality. Microbes dance, mingle, fuse and partner within human bodies, not only affecting health, but our cultural and social reality. With help of these tiny agents many cultural expressions are made possible, such as through fermentation that expresses a synthesis between local resources and microbiomes. The attentive consumption of fermented or microbially altered goods, such as wine and cheese, gives feedback on the health of an environment. Cultural ties are more precisely expressed by similarities in the gut biome than through DNA: a life together within a shared space and shared food, intimacy and hygiene slowly foster the same interior microbiome.