Artist: Phuong Nguyen

Exhibition title: The Wind Returns to the Soil

Venue: Tap Art Space, Montreal, Canada

Date: January 20 – February 27, 2022

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Tap Art Space, Montreal

Note: The exhibition’s checklist is available here

TAP Gallery is thrilled to announce the debut solo exhibition of one of its represented artists, Phuong Nguyen.

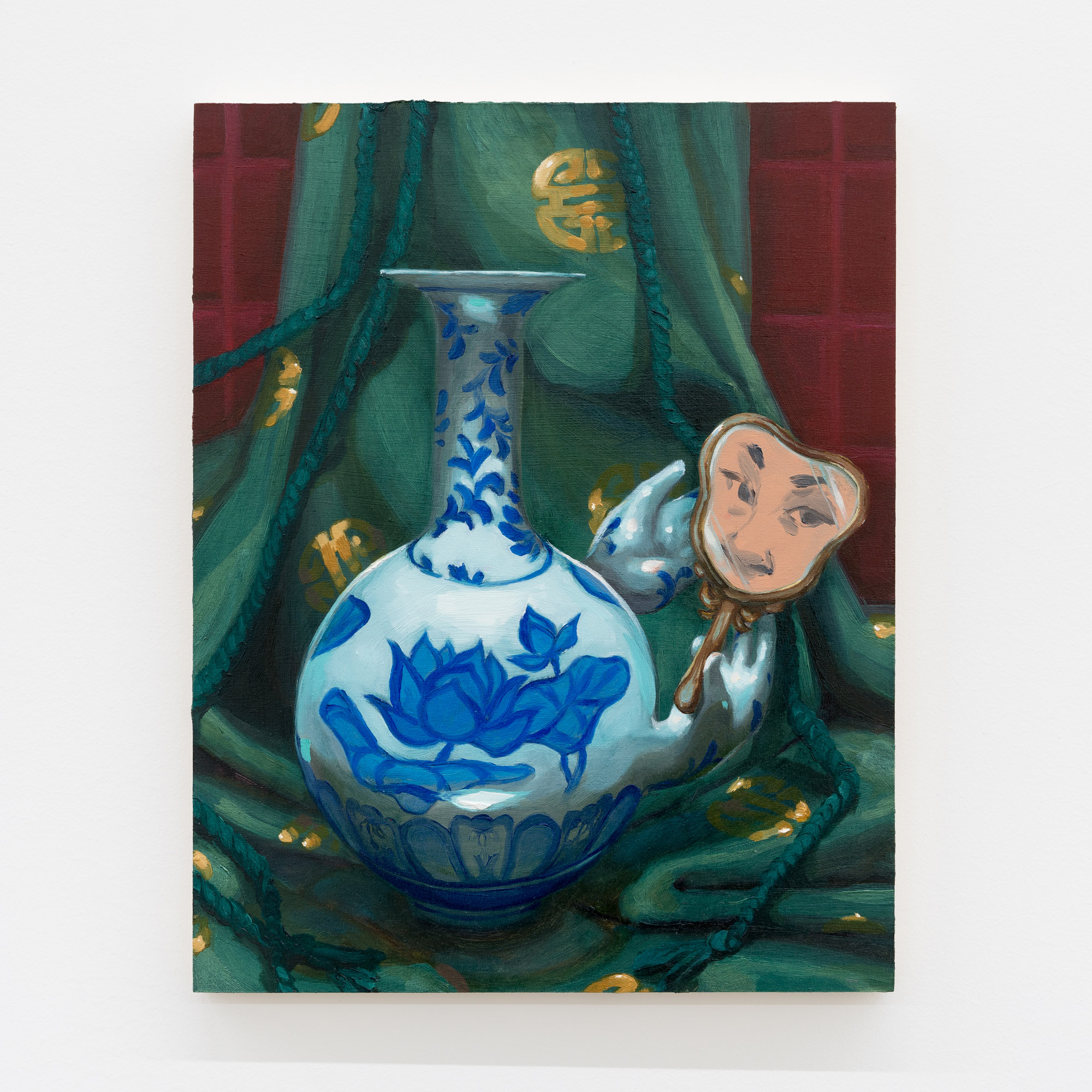

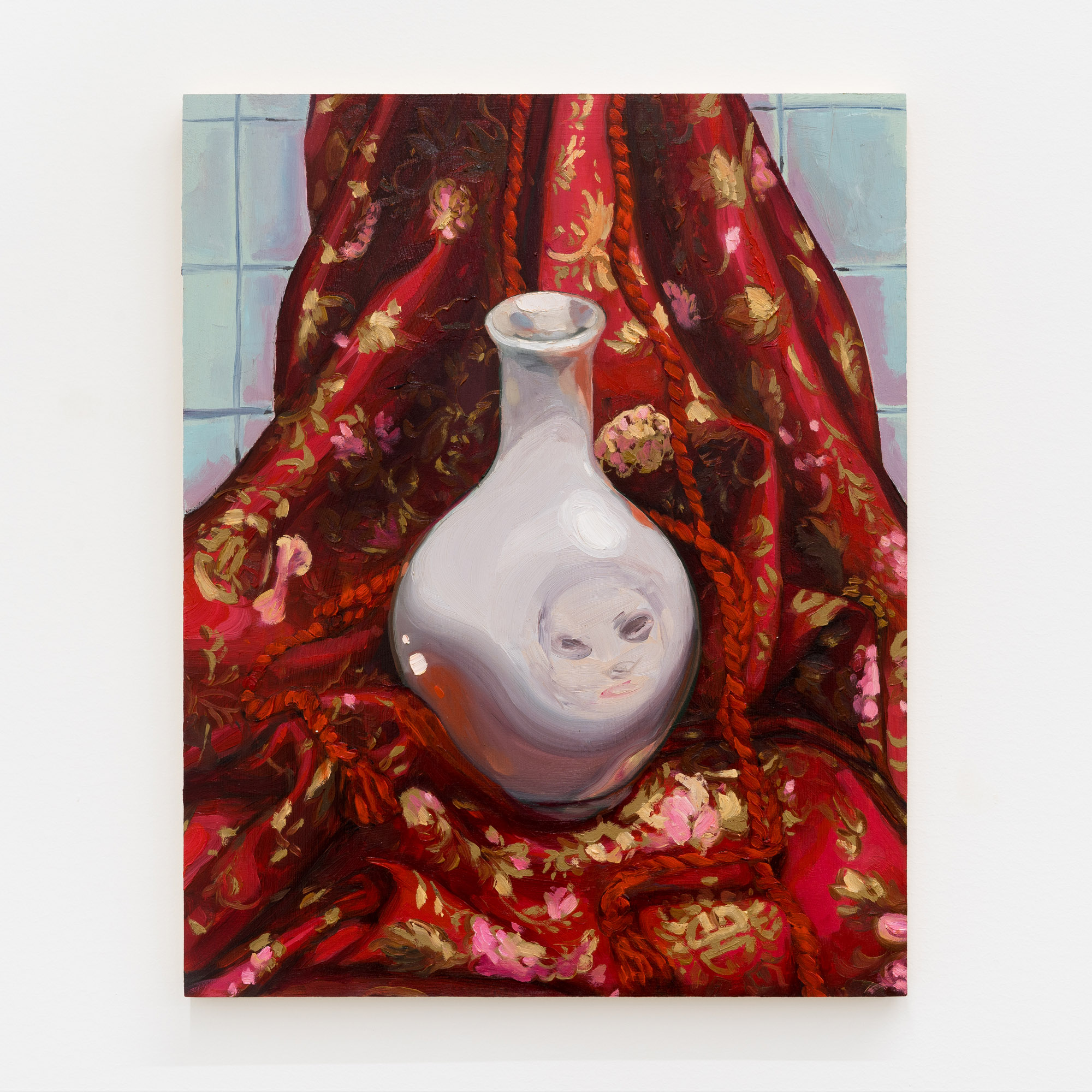

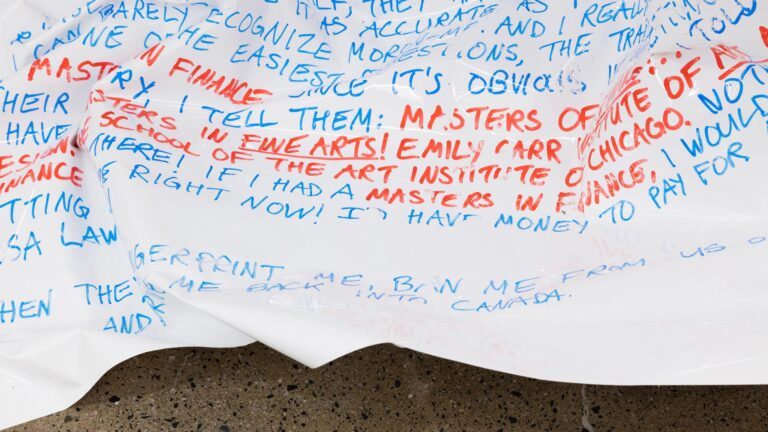

Phuong Nguyen uses imagery of broken ceramics in her paintings and mixed-media pieces. These elements serve as a time-traveling vehicle for transporting personal and familial traumas. Born in so-called Canada as a second-generation Vietnamese refugee, Nguyen’s work is deeply shaped by the themes of trauma, healing, and questioning concepts of self-tokenism. In her most recent body of work, imagery of hands and faces reflected in ceramics have started to appear alongside symbols of protection and longevity. Through her art, Nguyen explores the complexities of healing, and the idea that “Sometimes we never heal from our pain- and we never return to the version of ourselves that had existed before trauma. Sometimes we don’t ‘heal’, we only change”.

Shattering the Fantasy of the Self

By Amelia Wong-Mersereau

“The use of the adjective ‘diasporic’ […],” write art historians Alice Ming Wai Jim and Alexandra Chang, citing cultural anthropologist Lok C. D. Siu, “emphasizes ‘the processual nature of producing diasporic subjectivities.’”[1] Since the first issue of the Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas journal was published in 2015, exhibitions, events, and scholarship highlighting Asian diasporic artists have continued to grow steadily. That growth, which began several decades prior, has been slow and part of an ongoing tokenization by museums and galleries of ethnically diverse artists. The city of Vancouver only recently saw the opening of the country’s first Chinese Canadian Museum at a temporary location in 2020, and besides perhaps the odd Sobey Art Award winner, it is far too uncommon to see an Asian diasporic artist offered a major solo exhibition by Canada’s larger-scale institutions.

This discouraging context imbues exhibitions like Phuong Nguyen’s The Wind Returns To The Soil with importance. Since their move back to Montreal, TAP Art Space now represents Nguyen along with three other emerging artists. The gallery aims to support and grow alongside their artists, as well as their other collaborators. My approach in writing about this exhibition considers that processual nature that Jim and Chang so intentionally underscore in their use of the adjective diasporic. Through embroidery, painting, weaving, and a combination of the latter two to create mixed media sculptures, Nguyen articulates the complex subjectivity of a second-generation Vietnamese, born and raised in Toronto, Canada.

As the daughter of a Hong Kong immigrant myself, I am drawn to a number of the themes in Nguyen’s work, and even more so to how she unpacks them. For example, the vessel is the most prominent throughline in The Wind Returns To The Soil. At times the vessel is literally reaching out with human-like hands, and in other instances it is a mundane object transformed by ornamentation. But the majority of the works feature a broken vessel, either shattered completely or simply cracked on one side, which is the main key to understanding Nguyen’s art as an expression of a subjecthood that is becoming, hybrid, and not fixed.

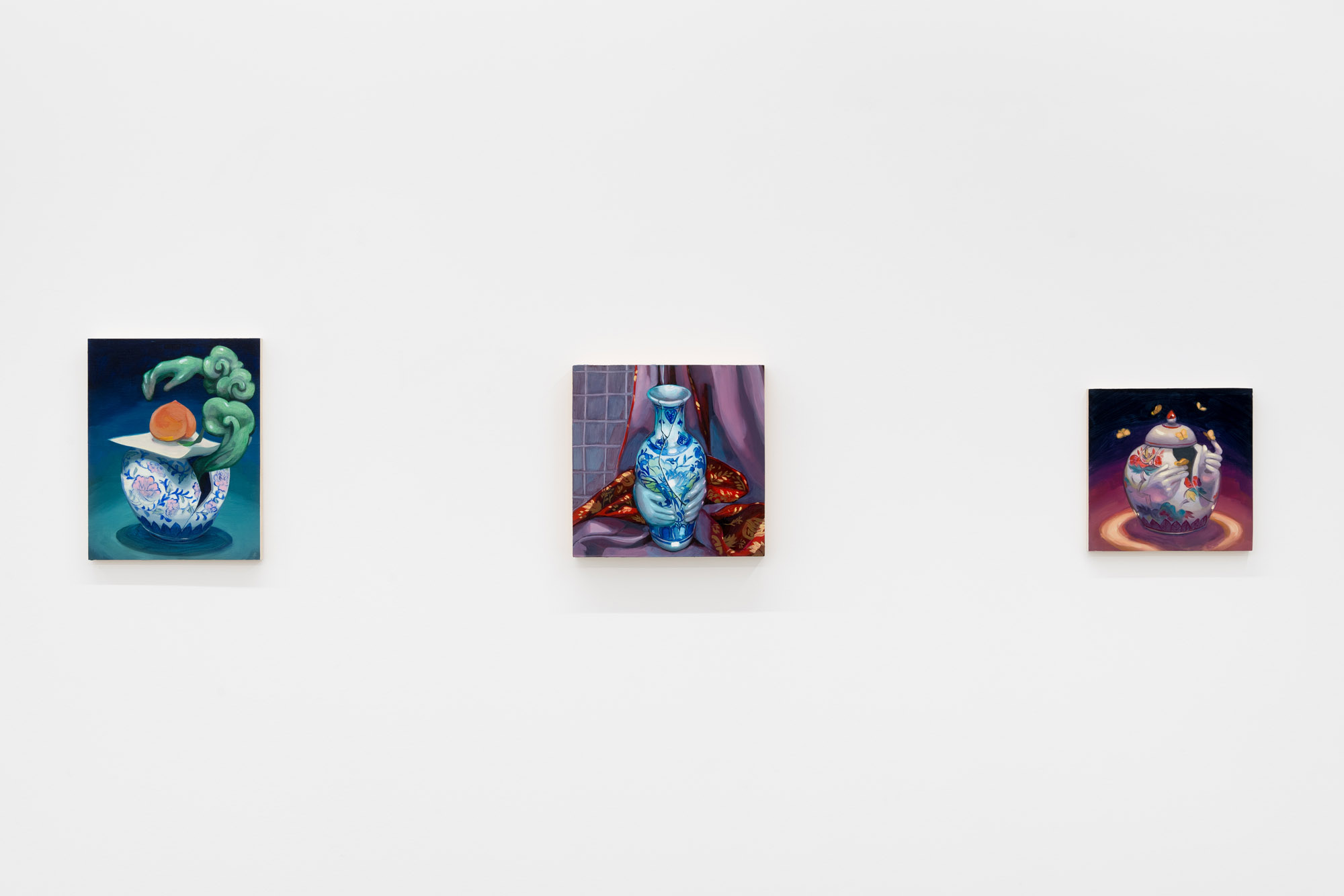

“Looking back on my work prior to this body, I was interested in the history of Chinoiserie,” she writes.[2] Culturally specific yet recognizable references such as the pagoda or lantern, auspicious colours and foods, or the blue and white motif of Chinoiserie, are all access points for western audiences to enter into an artwork’s subject matter. These references simultaneously function as opportunities for diasporic artists to bring contemporary and personal experiences into conversation with discourses of race, history, and culture. Chinoiserie has either been strategically referenced or directly incorporated into the work of diasporic artists across North America, like Sin-Ying Ho, Mary Sui Yee Wong, Patty Chang, Jennifer Ling Datchuk, Karen Tam, and Lan Florence Yee, to name a few.

The pieces of blue and white dishware were collected by Nguyen from friends, family, shops, and other various sources. Though she does not depict, as Ai Wei Wei famously did in 1995, the act of destroying any ceramic vessels, the shattering of each dish is present in the remains that make up the works. Each piece of dishware alludes to the violent act of its breaking, and thus their stitching back together a poetic and poignant gesture. In All The Light We Cannot See (2022) and A Separation of Self (2022), the artist incorporates small paintings of vases into a wooden frame with the jagged bits. She stitches them together using a brightly coloured twine that appears pulpy when it catches the light. Following the metaphor of the vessel as body, the red twine in Weaving Study (2022) looks as though it is growing organically within the frame, in patches the way a scab would over a wound.

The frame adds an intimate and voyeuristic quality, like peering in on a person’s attempt to pick up the pieces, dust them off, and embellish. These are defiant representations of the difficult experiences from Nguyen’s life, whether inherited or first-hand. For her, “pain can travel through generations but so can healing.”[3] American ceramics artist Jennifer Ling Datchuk’s Truth Before Flowers (2019) is similarly aimed at empowering women in the face of traumatic histories. In a photograph, she covers her abdominal scar with broken pieces of porcelain, a striking use of material to comment on resilience and fragility.

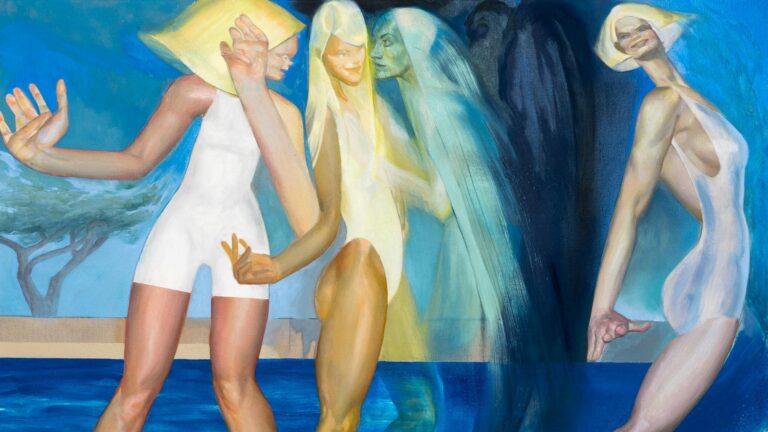

The warmth and softness of Nguyen’s paintings like Holding It Together (2022) and Ghost of Peaches Past (2022) contrasts starkly with the mixed media sculptures. Rich colours abound and butterflies flutter, creating a Disney-like fantasy, particularly with An Exorcism (2022), where a cloudy jade hand ominously reaches for a peach, or Sweet Baby Mango (2022) where the anthropomorphised fruit is sleeping. The ‘cute’ aesthetic of these still-life paintings is significant given their context as self-healing and self-protection for their maker. Asian women are characterized as easily consumed or existing for the pleasure of consumption, a racist viewpoint that has its roots in Orientalism. In my Master’s thesis I used cultural theorist Sianne Ngai’s conceptualisation of an aesthetic of the ‘cute’ to read artworks by East Asian women artists who work against their objectification and obfuscation. So while Nguyen’s paintings appear unthreatening in their softness, they are loaded with power, agency, and intention.

Finally, the vibrancy from the sculptures and paintings carries through to her series of embroidered plastic baskets. Peace Offering V and Peace Offering VI (2022) encapsulate all the themes of the show, as vessels from a distinctly domestic setting decorated through a technique traditionally associated with the feminine. They remain perforated however, much like human bodies, though we may try to plug up, cover, and repair every breach. The Wind Returns To The Soil presents a reparative art practice that reflects back to Asian diasporic subjects, and likely other marginalised groups, the experiences that link us together and make us whole again. In the artist’s words, “sometimes we never heal from our pain, and we never return to the version of ourselves that had existed before trauma. Sometimes we don’t ‘heal’, we only change.”4

[1] Alexandra Chang and Alice Ming Wai Jim, “Asia/Americas: Converging Movements” in Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures in the Americas 1, nos. 1-2 (2015): 1-2.

[2] Artist’s notes.

[3] Artist’s notes.

4 Artist’s notes.