Artists: Rosa Aiello, Lena Henke, Benjamin Hirte, Dozie Kanu, Mira Mann, K.R.M. Mooney, Markus Saile

Exhibition title: Our Porcelain Thoughts

Venue: DREI, Cologne, Germany

Date: May 23 – July 27, 2024

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and DREI, Cologne

Our Porcelain Thoughts compiles works by seven international artists, born in the 1980s and 90s, who have contributed and continue to contribute in different ways to the expansion of the landscape of object making. Considerung it a personal picture of the current moment, the exhibtion seeks to open a dialogue between multifaceted artistic approaches and asking questions around aesthetic considerations in the context of conceptual strategies.

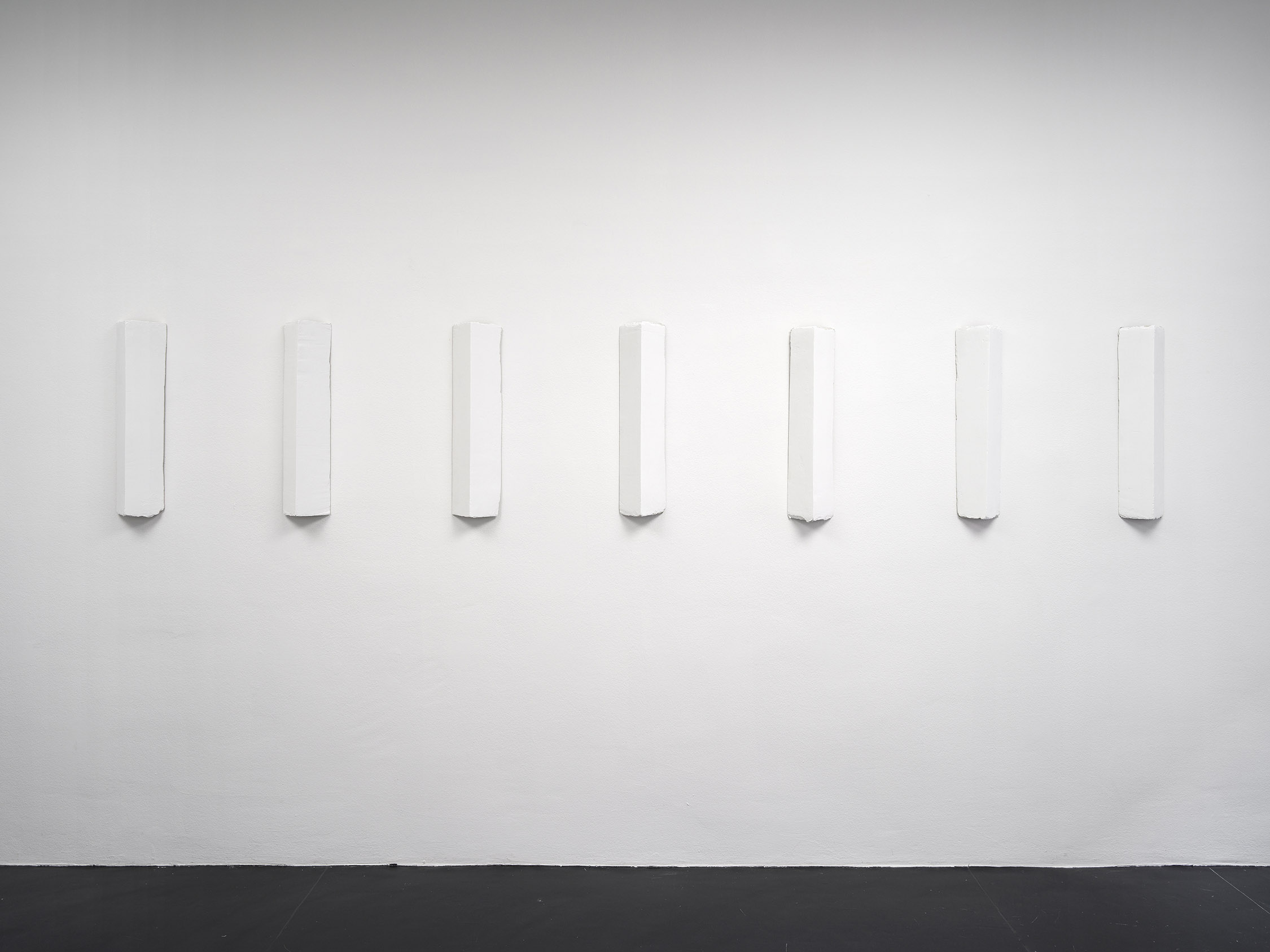

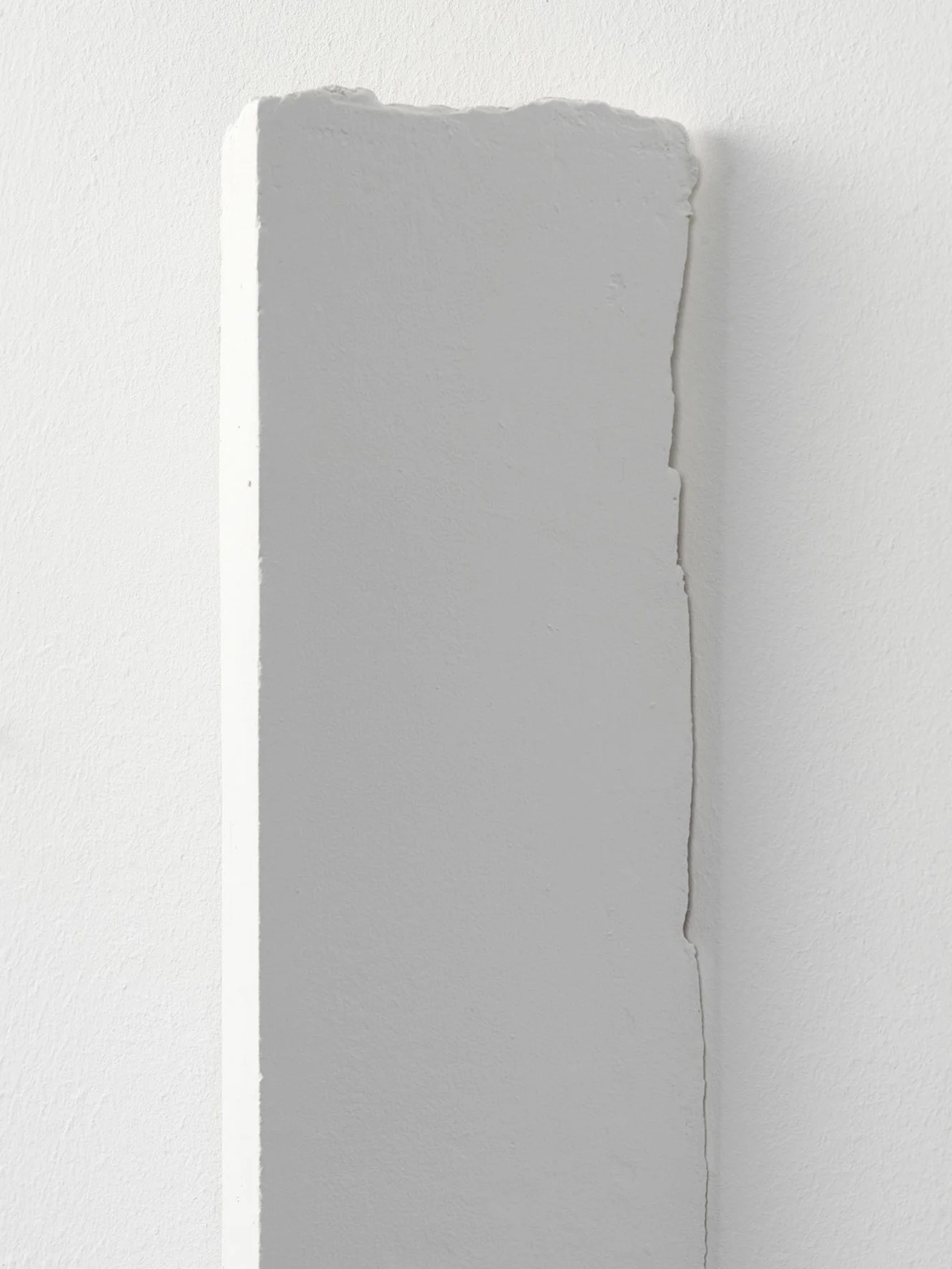

Rosa Aiello’s (b. 1987, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; lives and works in Berlin) works, whatever the material or genre, deal with narrative and time: most often moving image, image series, architectural interventions, sound works, and here, sculptural series. She takes an experimental approach and gathers material from what is at hand, in her domestic space, in her relationships, on her habitually used streets. She is interested in observing structures, social constructs like the family, and the built world of architecture and city infrastructure Lifesize (1-9) (2024) are in the tradition of minimalist sculpture. In this series, the artist exhibits a material problem: her acquisition of the skills involved in building and finishing walls with plaster. Each of the sculptures, whose dimensions are based on the length of the artist’s arm —a necessary size limitation which allowed her to make them without outside assistance or apparatus—represents an instance of an ongoing practice in search of a standard, and follows her desire to create a perfect corner, an ever receding absolute edge.

Throughtout numerous international exhibtions, Lena Henke (b. 1982, Warburg, Germany, lives and works in New York) has created her own dense cosmos of autobiographical and art historical references that imbricate sculpture, intimacy and feminism, in which multilayered narrations become distorted, details are projected into far horizons, micro and macro perspective interlace, melt into each other, mingle and alloy. Her practice is engaged with the complex power dynamics of identity and gender, interfacing with histories of art and architecture through appropriation, control, and submission. With the series of fictious New York street signs – one absend work of this series lent its title to the exhibtion – Henke turns outside in and inside out and the gallery space into a psycho-geographic projection, scaling the personal into a cityscape. Her interest in spaces is not limited to presentation or intervention in existing architecture; it is also revealed in a broader sense in the appropriation of objects, urban situations and psychological spatial constellations. Recurring motifs include interventions into the classic working methods of sculpture, recourse to anthroposophical methods, often through a biographically motivated approach or the control of “architecture“.

Sculpture in public spaces oscillates between works with explicit artistic aspirations, decorative architectural elements and aesthetically exaggerated infrastructure. It can take on representational tasks and reformulate traditional iconographies or reach into the social sphere to create identity. It is often integrated into larger programs and ideologies, for which the individual work is as much a means to an end as an independent artistic manifestation. It articulates its implicit function in differentiated topoi – the fountain, the monument, the facade decoration – but often loses its historical superstructure over the course of time to present itself only as furnishing of the urban space or commissioned art of past times – decorative, often decontextualized and yet an expression of an extensive (cultural) political will to shape.

In his works, Benjamin Hirte (b. 1980, Aschaffenburg, Germany; lives and works in Vienna) deals with such sculptural elements between aesthetically transformed functionality and ideologized monument, whereby he is interested in questions of integration into the urban space, but also the genealogy of a form. How are sculptures charged with a local social and political function and how has this been aesthetically transformed? Or, following on from this, where in the history of progressive urban design do the lines of conflict run between a radical modernist formal language and a realistic aesthetic that is perceived as more accessible? Vienna, where Hirte has lived since his studies, with its long tradition of social housing and the art programs associated with it, provides diverse material for such research, which finds resonance in numerous works or serves as a contrasting foil for dealing with public commissioned art, for example in the USA, and its inherent contradictions […]. (Vanessa Joan Müller)

The objects and installations by the American artist Dozie Kanu (b. 1993, Houston, Texas, United States; lives and works in Santarém, Portugal) are deeply connected to a topology of utilitarian objecthood and everyday culture, yet none of his chairs, sideboards or lamps are absorbed by their functional purpose. Rather, his sculptures are united by an inclination toward a form of meaning that transcends their utilitarian value.

Often starting from found and used materials taken mostly from their respective direct environment, Kanu combines such materials inscribed with traces and stories of their use over time with the slick surfaces of industrially manufactured material or readymades. By pairing these narrative qualities with an experimental formal language that brings an oftentimes surrealistic abstract quality to his works, he is constantly subverting the concept of clearly separated genres and concepts of the artwork.

Kanu’s works are both sculptures and design pieces, installations and set designs, artworks and functional objects. With his idiosyncratic symbolism that makes reference to elements and symbols within Black Music and street culture, to vernacular forms of expression as well as codes of Classical Modernism and Surrealism, Kanu questions the emergence of value within an object, the relations between unique artworks and mass products, and the interaction of history and biography as it manifests through the material world. In order to shift and upturn the values of art, of social and cultural affiliations, Kanu seeks to create these objects and constellations thereof that rather complicates and sets in motion the idea of being and belonging.

Mira Mann‘s (b. 1993, Franfurt / Main, Germany; lives and works in Düsseldorf) practice includes time based and site specific modes of working, moving image, and cross-media settings in which they explore fictional spaces and storytelling as a medium for visualizing social structures, collective memory, and new narratives within the play of identities. Their discursive scenographies evolve around transcultural relations of human and non-human agents and the glitches they generate between experience and memory, reality and fiction.

In each of Mann’s works, there is the suggestion that the artist’s practice as a performer is always present in how an object is staged or the action of a video is captured. As Mann’s work demonstrates, there is a theatricality in the viewing of contemporary art that places the viewer in an active role, as a participant, as an actor. While this “theatricality” was something famously levelled against Western minimal art by the American critic Michael Fried, who saw it as a debasement of modernism’s claim on the autonomy of the artwork— something apart from the world, self-contained, medium specific, without moral or political purpose—subsequent practices of performance art, conceptualism, and installation have made theatricality a strength in challenging such conservative assumptions. While this modernist vision of artistic practice relied on a philosophical grounding in the Western tradition that assumed a split between subject and object, from the perspective of Eastern and Western traditional arts alike, such a distinction is not naturally assumed nor sustained by medium specificity. Rather, an art such as pansori, which has both a moral purpose and is the result of various art forms working in unison, is more equivalent to strategies in contemporary art than it might first appear.

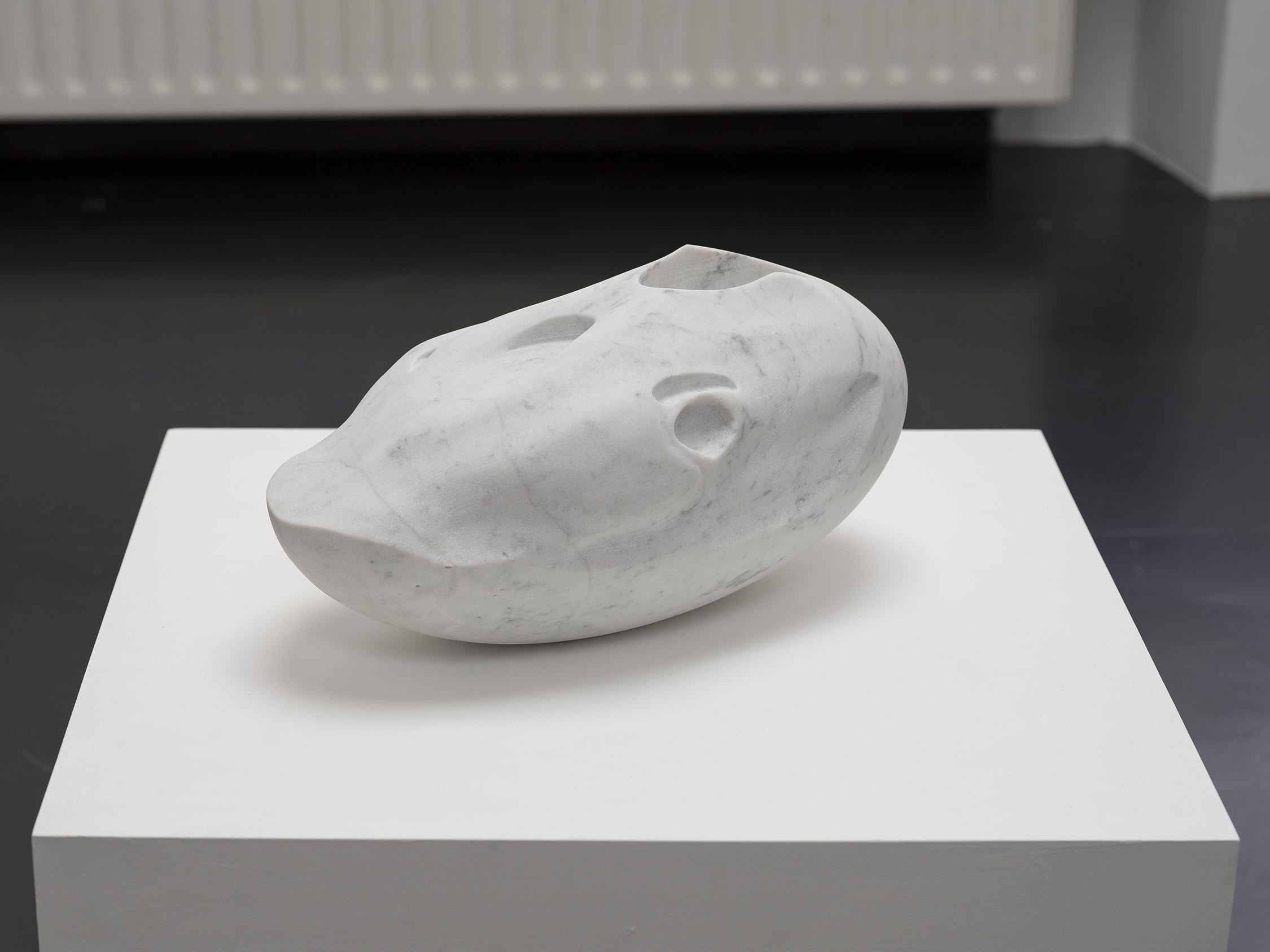

K.R.M. Mooney (b. 1990, Seattle, Washington, United States; lives and works in New York) is a subtle materialist. Like a chemist of sorts, his work focuses on the way materials and forms interact and impact one another. Grounded in a deep knowledge of materials and processes, his practice occupies an intermediary position between abstract, autonomous, and site-specific sculpture, a type of sculpture in which an acute concern for tactility, connectivity, and space constitutes a centrifugal force. Mooney’s objects distill the observable and imperceptible properties of organic and industrial materials, investigating structural capacities and potentials as well as the effects of time, temperature, and adjacency.

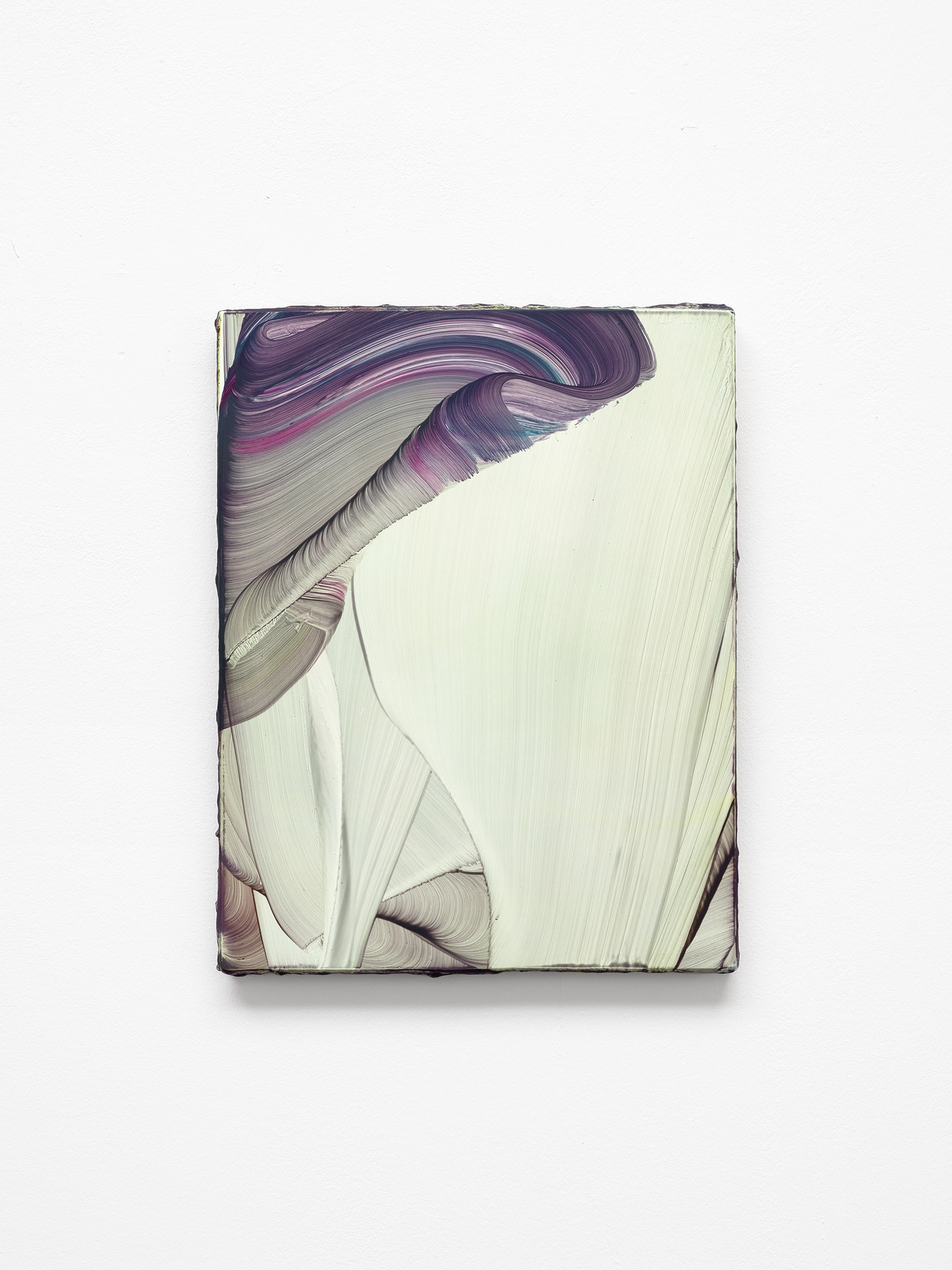

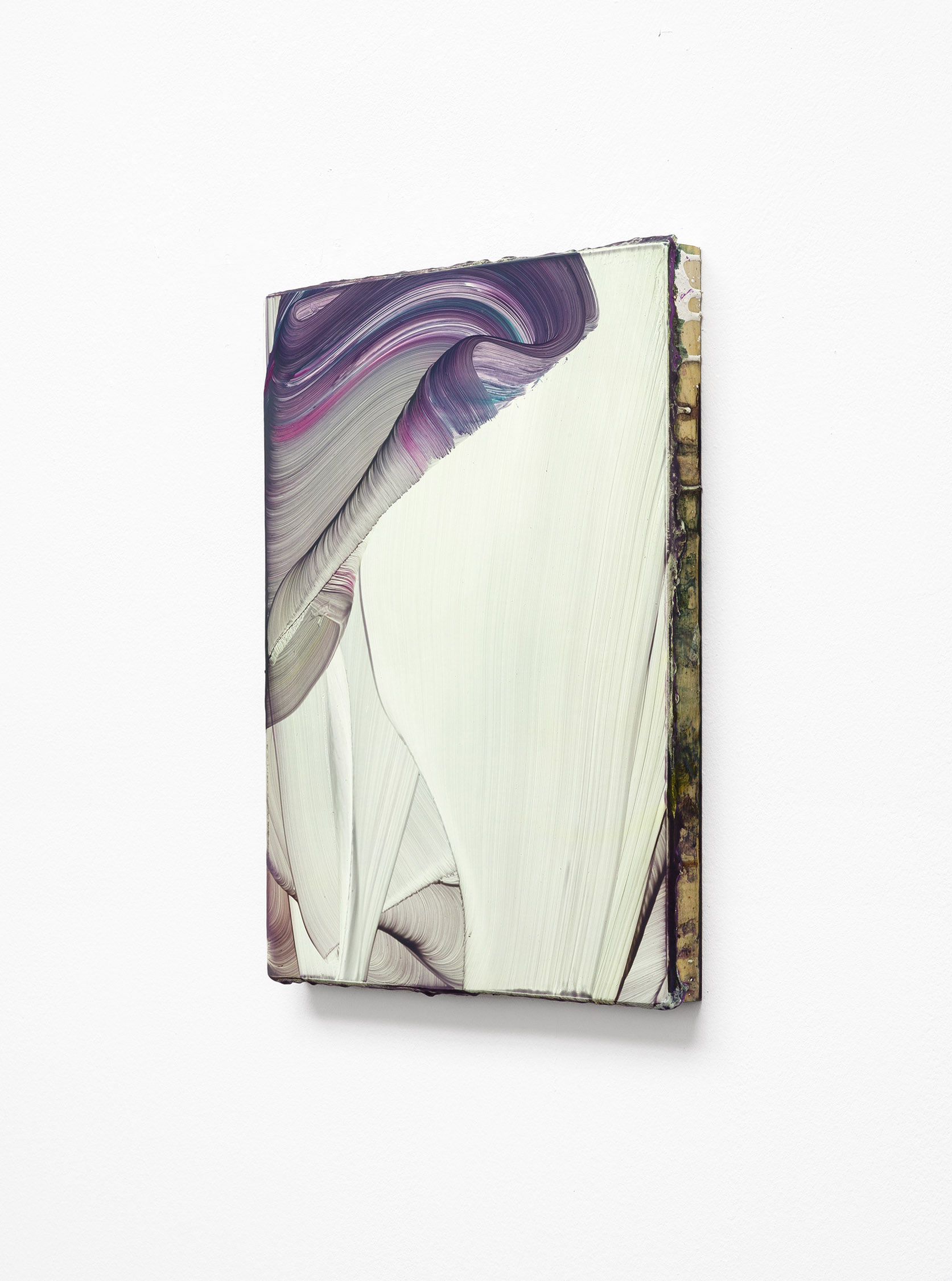

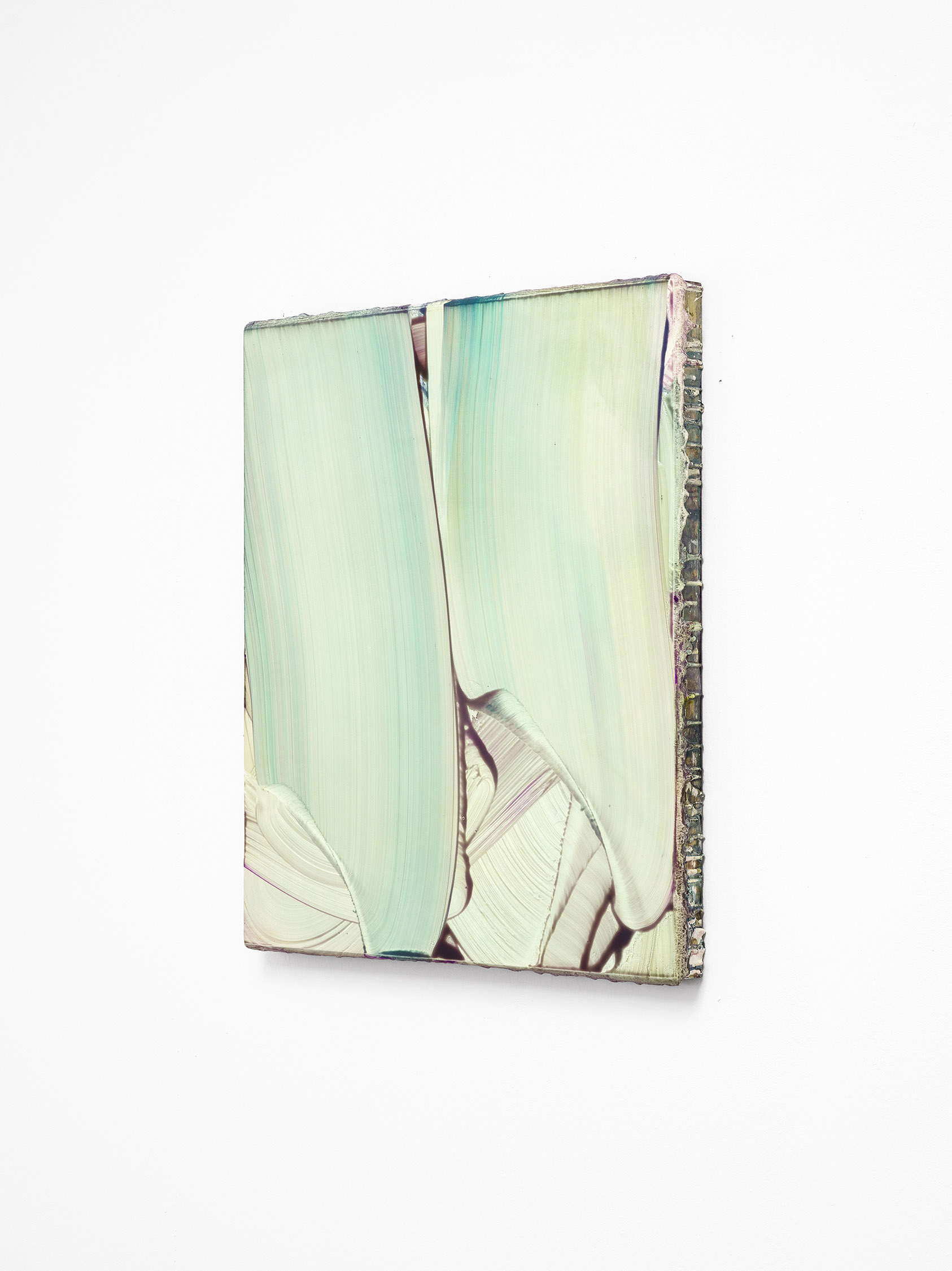

Markus Saile’s (b. 1981, Stuttgart, Germany; lives and works in Cologne) works convene the space of painting, in a subtle interplay between the space where it is situated, the space it represents and the space it constructs in dialogue with architecture. Thus, the in between space, in between the paintings, creates a space where we stand and move, as viewers. Pictorial problems thus can be understood as architectural problems, in the sense of a socio-political structure. Beyond the in-situ and the context, it is an investigation into painting in volume, the depth of the surface, and the extension of this practice into a performative field of action.

The current paintings are created in a process of overlapping layers of paint and thin veils that reveal their material life. Paint deposits accumulate at the edges of the supports, revealing the temporal structure of the painting process like the annual rings of a tree and lending them an object-like quality. Gestural interventions dramatize the pictorial space in the sense of a stage situation. The conceptual work with the painterly gesture thus can be understood as a kind of performative re-enactment of its historical, temporal and spatial potentials. In the painting process, the artist creates volume in one brush movement, like they do on Blender to create forms. His method can therefore be related to the extrusion process in 3D programs. Instead of putting a series of points together in a line, which is the drawing perspective work, one brush flow creates a plane in one gesture.