Artist: Micah Schippa-Wildfong

Exhibition title: all fish in the night become birds

Venue: ROMANCE, Pittsburgh, US

Date: June 8 – July 14, 2024

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and ROMANCE, Pittsburgh

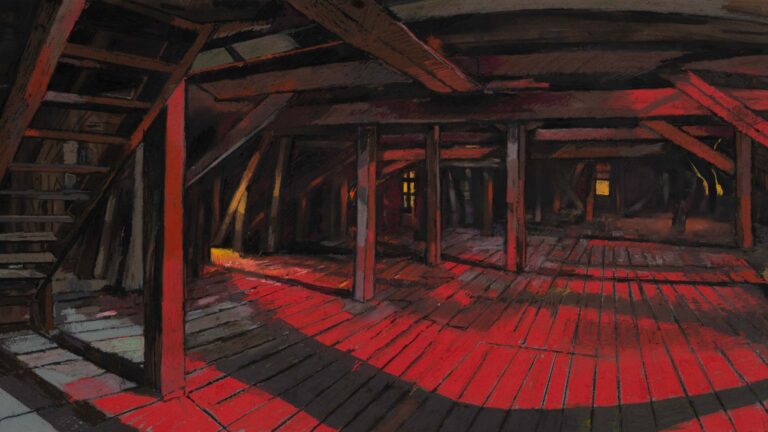

In all fish in the night become birds, Micah Schippa-Wildfong puts forward the proposition of “an exhibition as a score for a film.” Here, what is supposed to enhance the emotion of a narrative comes into focus as a set of material conditions by which a series of sculptures and ambient changes to the gallery unfold. Most recently turning their attention to live performance in their practice, Schippa-Wildfong has conceived of these objects, surfaces, and architectural elements as an open system in which they can short-circuit, liquify, and dissipate the “rational” ways we desire for inorganic objects and human beings to behave.

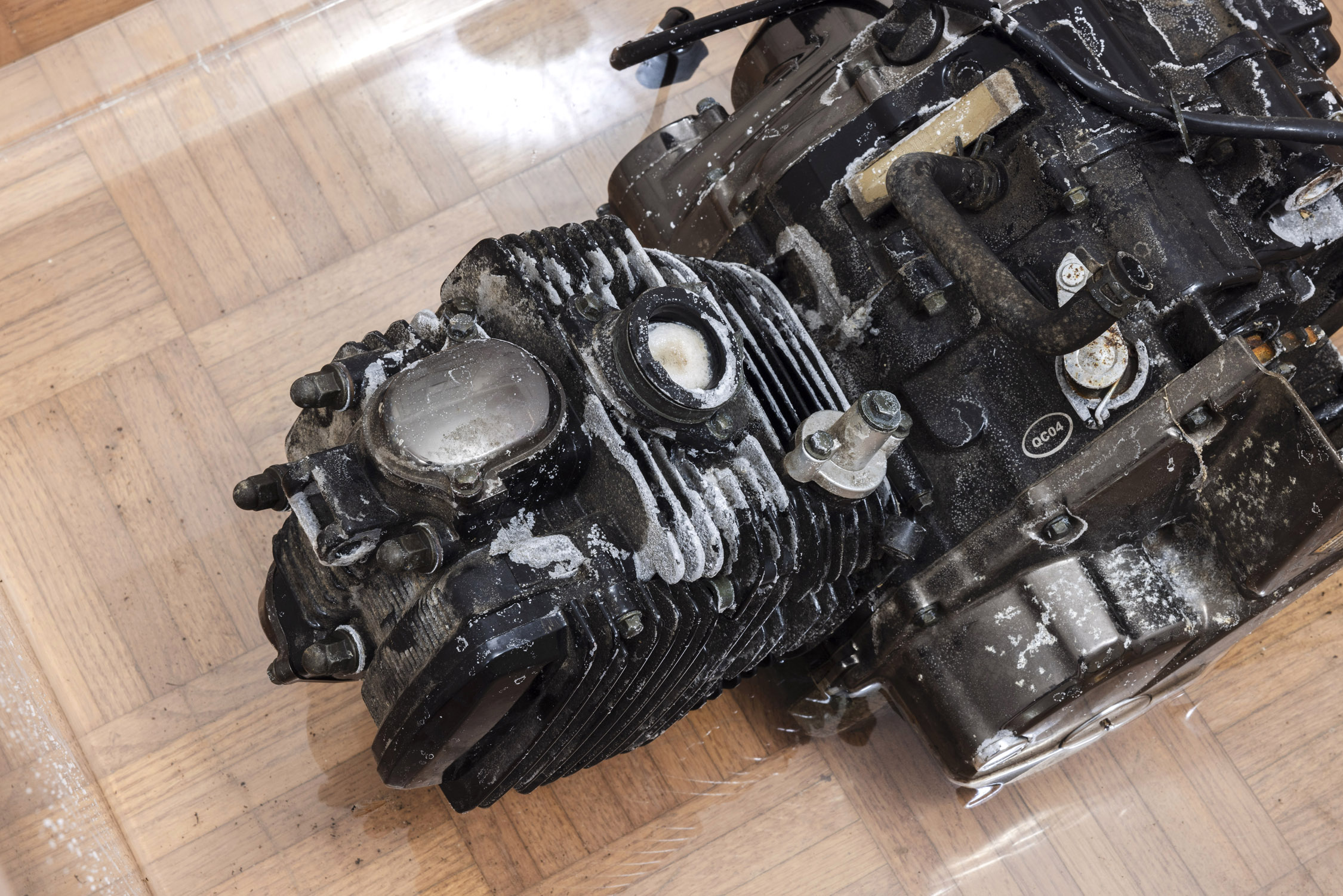

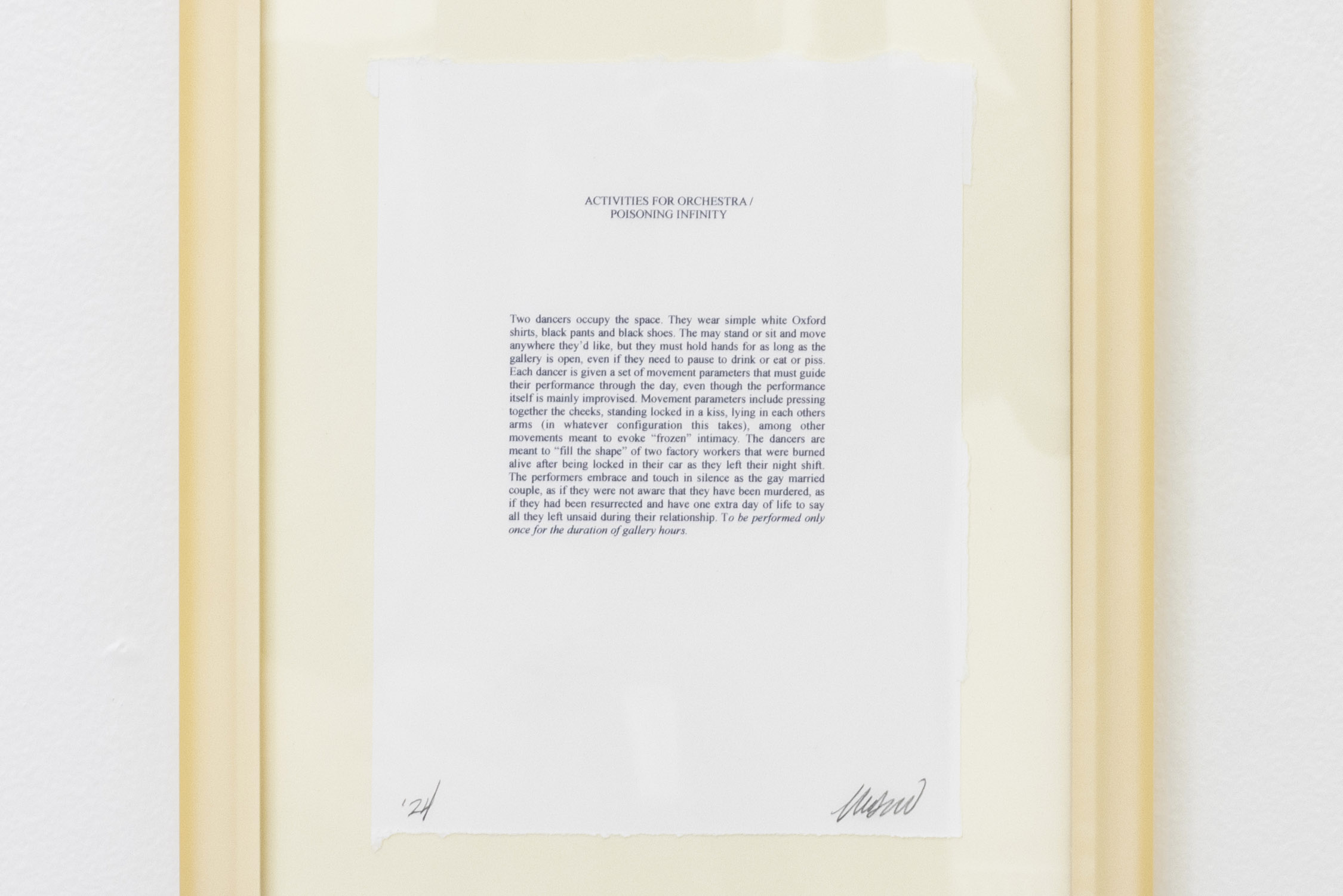

Throughout the show, different forms of registering and recording what seems evanescent (instructions for a performance based on slow, simple movements of “frozen intimacy” like embracing while sleeping or hand-holding; gallery windows fogged with industrially produced imitation snow interacting with air and moisture) annotate the occurrence of change without arrest. Or even, hasten it as in Hans Haacke’s Condensation Cube (1963-78), a resonant sculpture comprised of an acrylic cube filled with water as a study of interacting systems via surrounding temperature, analogous to the conditions by which we move in the world, and by which the world’s structures move us. But Schippa-Wildfong’s decomposing forms and poetics, such as a corpse-like motorcycle engine at rest in a vessel of chemicals approximating human tears, or a flute the artist’s mother played when she was their age, dissolved in a mixture akin to stomach acid, are less about physiological and institutional phenomena, or conversely about a kind of supernatural animism, than questions of how human meaning both cracks and accumulates in the presence of inevitable “disorder” over time: beige and rusted and yellowing, with the moisture of emotional and psychological transmission between bodies and the things we make to try and extend ourselves (or each other) beyond our limits.

Usurped from the context of utility and instruments of “power,” stripped of the ability to do things, tired and corroded, Schippa-Wildfong’s skeletal apparatuses and theater of their attenuated choreography enact feelings of “absence or weakness of agency” where “under conditions of ‘liquidity’ everything could happen yet nothing can be done with confidence and certainty,” as Zygmunt Bauman writes in Liquid Modernity (1999). Or as the artist describes: “What, in the end, stays written, whether by notes or by word, of our presence, if not dust and vapor. In the floating decay of metal and acid there is so much more than just our minds or their breaking down.” From the wider sickness of bodies treated as containers, machines, or motors for productive activity, to the compulsions of the artist’s grandfather to amass a collection of technological mechanisms as a manifestation of his mental illness, Schippa-Wildfong distinctively seems to ask: what would it look like, if decay and loss weren’t something to romanticize or fear, but to simply coexist with—not in order to suppress the reality of it, but to sit with it, feel through it, and, thus, process it more thoroughly? Maybe they would be dancers, or a kind of spectral metronome in the form of fluorescent tube lights flickering, in sync to a timer without the legibility of a clock, melting between “real” and theatrical and imperceptible measures. In the artist’s words, “Only from THE incomprehensible do I feel affinity, or love, or the possibility of either, only in that constellation of indeterminacies.”