In her practice, New York-based sculptor Bat-Ami Rivlin often makes use of unassuming, mass-produced materials such as zip ties, tires, and metal shelving, deploying them in deceptively spare arrangements that bends their intended functionality to logical but self-negating ends. Rivlin’s work is sometimes positioned within a framework of material appropriation—minimalism-inflected commentary on industrial production and the built environment. But although this framing informs her work in a general sense, Rivlin’s practice is ultimately in pursuit of something more slippery, delving into the tensions between phenomenological experience and the cognitive determinism produced by language and context. Her works quietly disrupt and reorient the relationship between familiar materials and the ways we perceive them, acting as subtle perturbations in the cognitive-linguistic mesh that holds our understanding of things and their functions together.

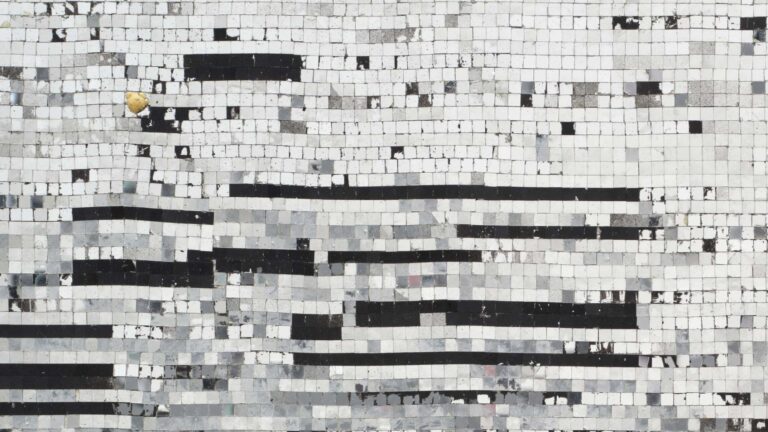

For her project at lower_cavity, Untitled (car, eyeballed), Rivlin scoured local auto wrecking yards, compiling a motley assortment of dented and battered car parts: mismatched bumpers and seats, a steering wheel assembly, the sinuous tendrils of a complete electrical system. Over the course of several weeks, she reorganized these elements into a precarious arrangement that generally resembles a car—one of the most recognizable objects of contemporary existence—but only in the loosest and most contingent sense. Appearing to be simultaneously on the verge of flying apart and in the process of congealing back together, the work is less of a reconstruction of a car than a tenuous evocation of the general idea of one— a fugitive impression of car-ness barely held together (physically and perceptually) by industrial zip ties, masses of duct tape, and the physical architecture of the space itself.

As we move through Rivlin’s installation, our view of the work is continually punctuated by the heavy brick support columns that run the length of lower_cavity’s main project space—staccato visual obstructions that operate like the spaces between frames of a slowed-down film. Through these interruptions in viewing and the fragmentary, provisional nature of her reconstruction, Rivlin disrupts the illusion of continuity that characterizes conscious experience, literally breaking it into pieces. The phenomenology of the car—how we mentally construct it—is central to the work: Rivlin is far less interested in accurately representing a car than she is in aggregating a semi-random collection of qualia associated with one. By arranging automotive parts in a way that suggests their original purpose without fully restoring them, Rivlin exposes the cognitive shortcuts we use to understand everyday objects. Untitled (car, eyeballed) operates like a physical manifestation of how the average person might attempt to draw a car from memory: a shaky sketch composed from incomplete fragments of the thing being sketched, with only the most general understanding of its inner workings.

Extending out from the central grouping of fragments, individual parts—headlights, front grills, seat belts—reappear in ever-looser arrangements that evoke the presence of a car in diminishing ways: utterances in an ever-more broken visual syntax that further underscores the gap between our conceptual understanding of objects and their material reality. Untitled (car, eyeballed) forces us to engage with the curious status of these highly manufactured components: each is irreducibly part of a car, yet inert and functionless when removed from the larger structure and context to which it belongs. While the car is often seen as modernity’s avatar of mobility and freedom, in isolation its individual parts become oddly lifeless, entombed within their predetermined function but no longer able to perform it.

This estrangement resonates deeply within the setting of lower_cavity, housed in the remnant of a former paper mill in Holyoke, one of New England’s many deindustrialized mill towns. Once epicenters of late 19th and early 20th century manufacturing, these cities are themselves fragmented artifacts of their former purpose and functionality. This post-industrial context lends an additional thematic layer of material decay and economic decline to Rivlin’s project, in which the automotive scrap industry can be seen as a proxy for a broader social and economic transformation within a culture that has so strongly entangled its identity with that of the car. Against this backdrop, Rivlin’s patchwork construction acquires a sharper critical undertone, suggesting a larger shift from a state of production to a condition of scavenging.