Pole Bending Romina Abate and Anna Holzhauer in basis project space Frankfurt

In Romina Abate and Anna Holzhauer’s first collaborative exhibition “Pole Bending,” a sensibility for our present condition emerges. Holzhauer fragments and slices apart a once connected “Ständer” (2024), translating as “stand”, and reminiscent of a leaning bar for bicycles, a railing, or a balustrade. Yellow varnish evenly meets warm wood. Comfort. Yet the interlocking structure is no longer a self-evident, everyday object. It is no longer a supportive architecture in public space that can be grabbed or used as a backrest. Split apart, “Ständer” lies on the ground. Visitors step over its pieces.

Demographic numbers, anti-democratic forces, economic balances, a polarized society, and comparisons to the decline of the “West” akin to the Roman Empire: presently, it feels as if the stable and familiar are increasingly fragile. Holzhauer’s series “Ständer” might be a sculptural articulation of this associative feeling. But where to find hold? Visitors are encouraged to make their way through the exhibition, navigating the hurdles.

Romina Abate turns to the familiar, playful, and childhood-evoking in search for stability: the artist rides, vaults, and swings on a sea-blue rocking horse. As the photographic series shows, finding and maintaining balance requires a calibration of control and letting go, autonomy, and trust in the support. Yet even in Abate’s performative self-portraits, the search for equilibrium is complicated: the metal structure, typically firmly anchored in a playground, sits atop the unsteady surface of a wooden wheel board.

“Pole Bending,” the title of the exhibition, literally evokes sculptural questions that Anna Holzhauer addresses artistically. Gestures, experiences and memories, the landscape and lines in space are captured by the artist in drawings. Graphically, they rise from this reservoir into the tangible; color fills form and becomes materiality.

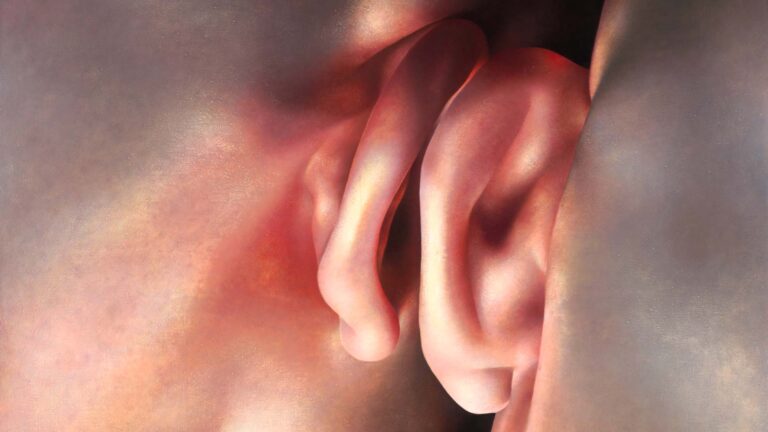

“Pole Bending” is also a discipline of rodeo riding. Male myths, the violent expansion of the U.S. frontier movement, the fiction of the white cowboy hero, and a history of cultural dominance resonate within the term. Historically, many early practicing rodeo women and cowboys of multicultural origin have been excluded; the iconic “Marlboro Man” has swallowed his own history. To this day, rodeo events enact intertwined social and gender configurations. Romina Abate’s watercolor works address the symbolic weight of equestrian sport. Soft movements, encased or mounted poles, hurdles, and bends that evoke genitalia or dildos play with associations of sexual intercourse and sexuality that have been linked to horse riding for centuries. Performatively, Abate conquers narratives of masculinity on the spring-mounted horse – searching for poise and looking firmly ahead, using a remote self-timer instead of reins.

In “Pole Bending,” Anna Holzhauer and Romina Abate present a thoughtful setting without – and this is crucial – leaning into single-sided judgment. The exhibition marks a moment of listening, looking both forward and backward, and searching for stability on uncertain grounds. Simple answers and outdated “Ständer-Logiken”[1] are worn out; it appears essential to dissect, transcend, and find new paths. Stability does not arise from a unilateral, preformed pose. Instead, the seesawing on the rocking horse upholds the importance of play and balance – on the shaky ground of an uncertain present. In an unstable world, the solution lies not in polarization but in the bending of poles, the playful rocking in fragility, or the balancing move across hurdles. “To play the double bind,”[2] as the thinker Gayatri Spivak writes.

[1] In German, “Ständer” translates not only as “stand”, but colloquially refers to an enlarged state of the phallus.

[2] Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty: An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization, Cambridge, Mass. / London 2012, 12. „Only an aesthetic education can continue to prepare us for this, thinking an uneven and only apparently accessible contemporaneity that can no longer be interpreted by such nice polarities as modernity/tradition, colonial/postcolonial.“ Ebd., 2.

Text: Tarika Johar