Artist: Ximena Garrido-Lecca

Exhibition title: Reverse Engineering

Venue: CAN Centre d’Art Neuchâtel, Neuchâtel, Switzerland

Date: June 10 – August 6, 2023

Photography: Sebastian Verdon / all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and CAN Centre d’art Neuchâtel

Reverse Engineering has both a product and a plant at its core. Its many names include apuga by the Cuicatec, a’xcu’t by the Totonac, cuauhyetl, picietl and yetl by the Nahuas, kuutz by the Mayans, gueza by the Zapotec, hepeaca by the Tarahumaras and many others – we could also mention tsibatl by the Arawak people in the Caribbean, because this is the term from which the word tobacco was derived. The diversity of names for this psychoactive plant comes from its long relationship with human beings since the Palaeolithic shamanism of the native peoples of the Americas. The plant was cultivated over a vast territory extending from present-day northern Argentina to southern Canada when it was “discovered” by the Conquistadors at the end of the fifteenth century [1].

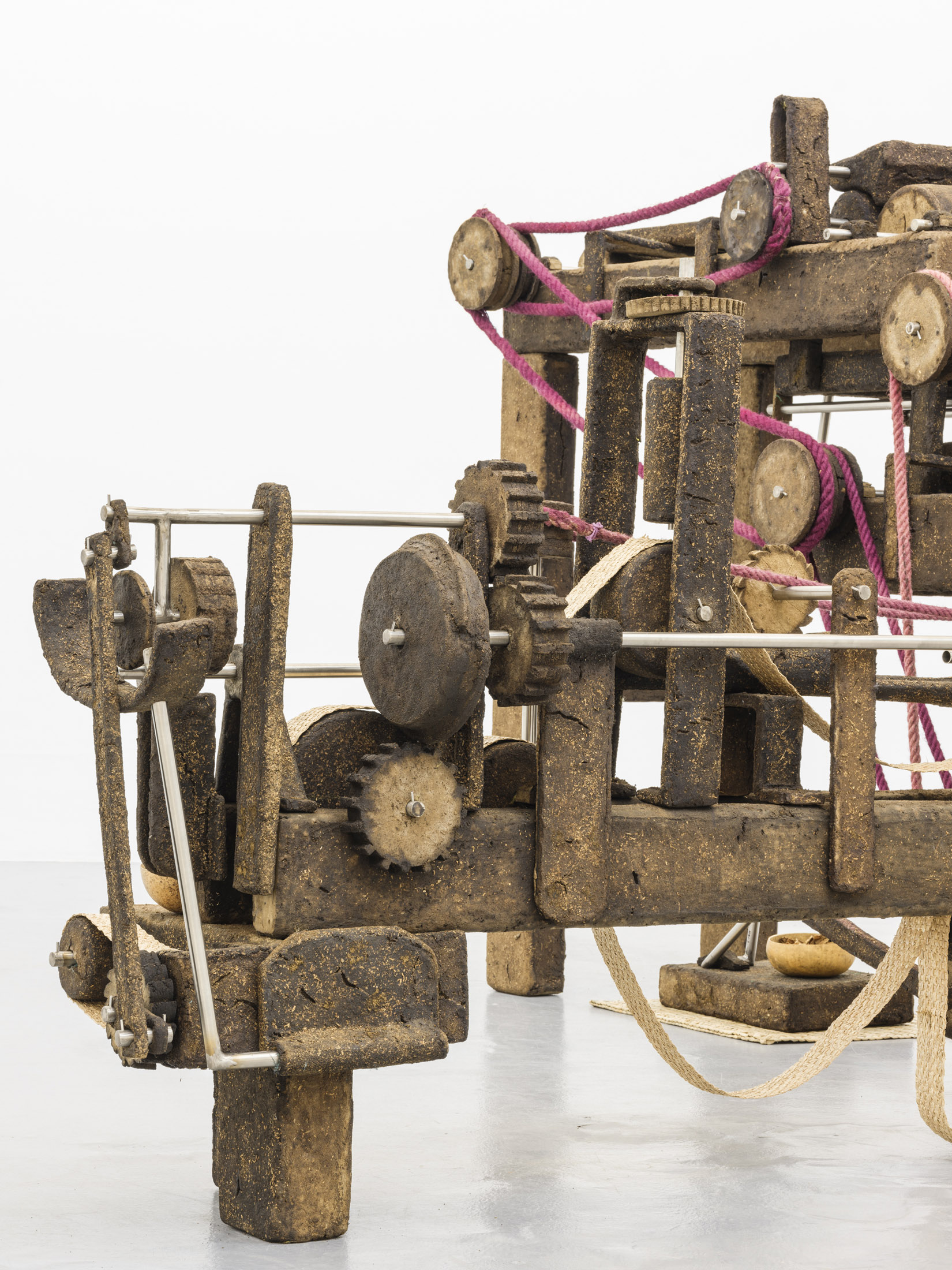

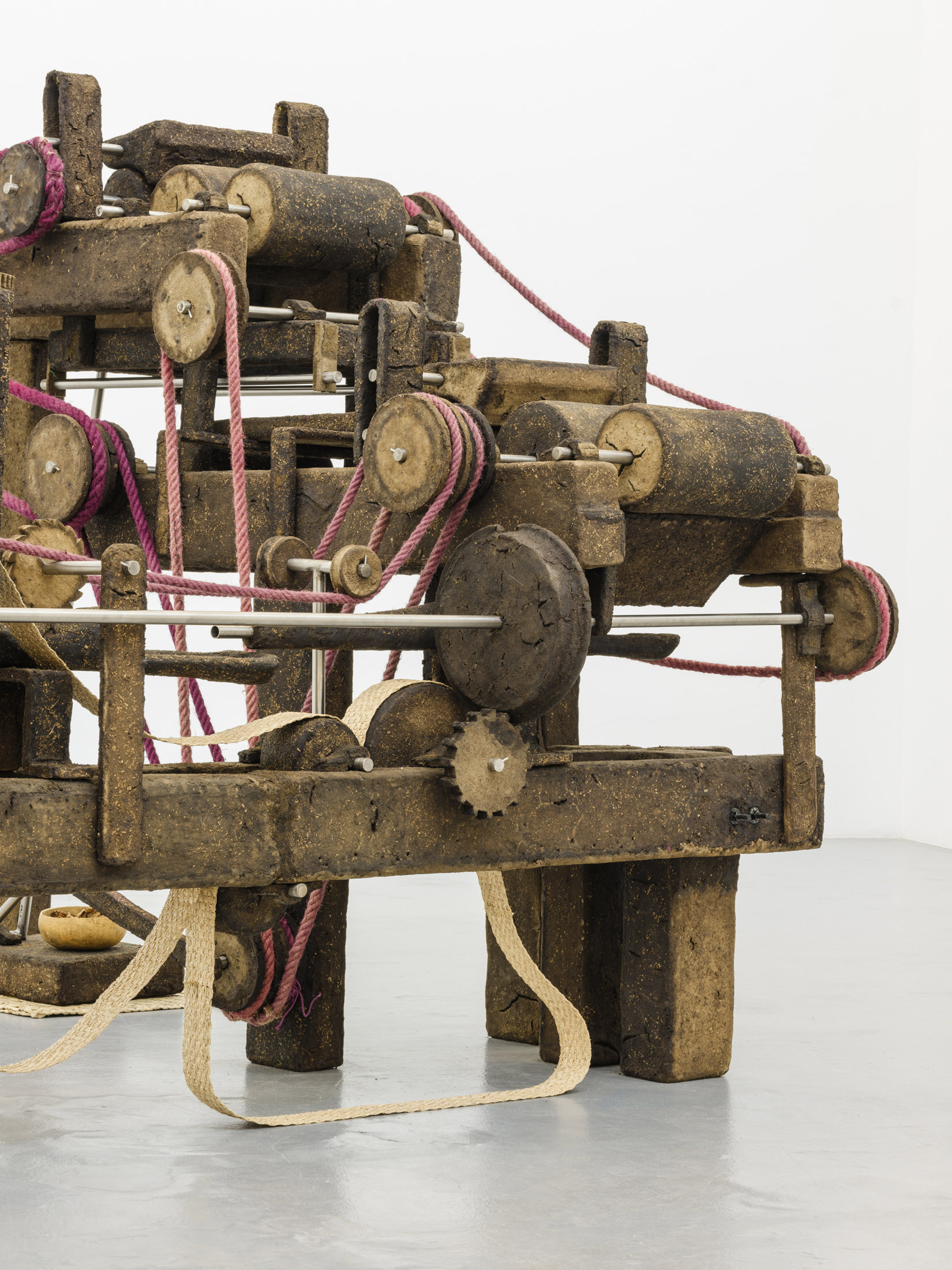

In Ximena Garrido-Lecca’s exhibition, visitors brush past the brown leaves hanging from wooden drying racks before coming upon what looks like a big machine. She built it following the diagram in the original patent for the world’s first cigarette rolling machine. Invented in 1880 in the U.S. by James Albert Bonsack, it could produce 200 cigarettes a minute, and gradually replaced the workers who used to make them in Virginia factories [2]. But while the shape of this sculpture references one of the main machines of the so-called Western industrial era, the materials she used come from a totally different kind of source. Each part, each cog, is made of ground tobacco transformed into a kind of putty with the addition of ashes. This is a mixture traditionally used by the Nahuas in the state of Guerrero in Mexico, where it is rolled into a small cylinder and dried in the sun until it becomes as hard as rock. The resulting object is called a San Pedrito (a diminutive of Saint Peter, a name derived from the Latin and subsequently Spanish word for rock). It is a sacred therapeutic remedy employed in rituals[3].

The Nahuas’ ancestors used the tobacco plant in traditional medicine and religious rites. Their system of classification of all the world’s things, animate and inanimate, is based on their correspondence with deities. For example, designating a plant by its sacred name also means calling upon and praying to the corresponding god or goddess. When it is used for divination, purification or healing, what’s at work is not just the plant but the deity that “inhabits” it. Tobacco is often associated with the god Quetzalcoatl, also known as the feathered serpent. When this is the case, tobacco can also be called the names used for “the Green Divinity”, “He whom the wind-blown leaves resemble” or “Bright green with long leaves”. From this angle, to understand both its traditional usage and the relationship that governs both humans and plants, we can’t separate its symbolism from its material qualities. The name and the ritual are just as inseparable from the treatment of illness as the plant itself 4. Later these practices and beliefs became absorbed into Catholicism, whether by violent means or simply over the course of time. But while Quetzalcoatl may have become Saint Peter, the old gods retain a living presence.

The course of the exhibition might recall a symbolic progression. Tobacco plant leaves guide us to the CAN’s very heart where the remedy-sculpture sleeps. That piece reverses the whole process: it is a copy of a machine that supplemented human labour and brought forward mass production instead, and yet the material it is made of takes us back to the organic and human. It’s a kind of giant San Pedrito deeply rooted in the world of the sacred, a ritualized mode of production in which a human act is end in itself. The raw material, in this case tobacco, even transformed by human hands, is no longer a plant product meant to be consumed. It is something worked not only for its properties but especially for its symbolic value, its place in economic, biological, social and even mystic systems. It enters into a relationship with human beings on multiple and highly diverse levels. Recognizing living beings in their otherness, in their complexity, in the roles they play for each other, enables us to discover our own unity with what we thought was meaningless for us and entirely disposable. This is a condition of the principle of reciprocity, the principle that enables equal exchange. Ximena Garrido-Lecca’s practice thus raises a number of questions about the relationships we maintain with what surrounds us, and the value system contained in these relationships that constructs us as human beings, or more precisely as modern human beings. Perhaps this is an invitation to reverse-engineer our societal machine, to deconstruct it so as to understand how it works and perhaps improve its mechanisms, and perhaps turn our all-encompassing, deadly machine into a more sensitive organism in which our relationships with others, with living things in general, take the form of mutual interaction, respect and mutual aid.

[1] Beatriz Barba Ahuatzin, Antropología del tabaco, Ciencia, october-december 2004.

[2] Unknown author, History of the Bonsack Machine Company. North Carolina State Digital Collec-tions, consulted on https://digital.ncdcr.gov

[3] Lilián González, Tenexyetl: el tabaco en la tradición nahua de Guerrero, Artes de México, no 127, 2017. Consulted on https://jstor.org

[4] Ibid.

“ ¡Pedrito! ¡Pedrito! / Tú le vas a quitar lo que tiene esta persona en su cuerpo / ¡Pedro! ¡ay, Pedrito! / Pedro, ¡Pedro xoxouhqui! [verde] / ¡Pedro xoxouhqui! / ¡Pedro tlatepacholli! [que ha recibido pedradas] / ¡Pedro tlatezotzontli! [golpeado] / ¡Pedro xoxouhqui! / ¡Pedro tlatepacholli! / ¡Pedro! tú vas a curar a esta persona / Le quitas lo que tiene / Va a vomitar lo que comió / ¡Pedro!, tú lo vas a dejar bien. ”

“ Pedrito! Pedrito! / You’re going to take out whatever this person has in his body / Pedro!

Make him well / Pedro! Pedro! Pedro! Oh! Pedrito! / Pedro, Pedro xoxouhqui! [green] / Pedro xoxouhqui! Pedro tlatepacholli! [who has been stoned] / Pedro tlatezotzontli! [beaten] / Pedro xoxouhqui! / Pedro tlatepacholli! / Pedro! You’re going to cure this person. / Take out what they have. / They’re going to vomit what they ate. / Pedro! You’re going to leave them feeling well. ” 1

1. Incantation of a Nahu healer, Lilián González, Tenexyetl: el tabaco en la tradición nahua de Guerrero, Artes de México, no 127, 2017. Consulted on https://jstor.org