Artists: Warre Mulder and Tom Poelmans

Exhibition title: DE HELD ZWEMT ALTIJD STROOMOPWAARTS

Venue: DMW Art Space, Antwerp, Belgium

Date: April 14 – May 7, 2017

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and DMW Art Space

THE OUTSIDER

L’ art ne vient pas coucher dans les lits qu’on a faits pour lui; il se sauve aussitôt qu’on prononce son nom: ce qu’il aime c’est l’incognito. Ses meilleurs moments sont quand il oublie comment il s’appelle.

(Jean Dubuffet)

“Have you not heard of the Outsider, who is talked about by a great many people, yet seen by so few? Some say this is due to his aversion to a social milieu and his preference for isolation, while others believe he comes and goes in various guises and is therefore hard to recognise. According to different accounts, the Outsider has been sighted in the eyes of an innocent child at play, in the wild gestures and nonsensical murmur of the village idiot, or even among tribes in the deep, intricate wilderness of the most savage jungle. There are also those people who claim that, once you get the chance to detect him, he has vanished already.”

“Admittedly, these are all just rumours, stories and speculations. Still different, more sophisticated theories are in vogue. Wiser men, for instance, have asserted that the Outsider has gone extinct, as if he were some rare and exotic species, and we have only ourselves to blame for it. It has equally been suggested that his existence has never been more than a myth or a mental construct, an invention rather than a discovery. This is why, when the Outsider is being mentioned by an unthinking commoner, laughter and sniggering is provoked among noblemen, often accompanied by air quotes, as if his existence is not to be taken seriously. ”

⌘

Nevertheless, the Outsider regularly appears to express himself in pictures and statues of all sorts, revealing very little of his well-kept mysteries. Elusive or eccentric would be apt words to describe them; far out of the ordinary, seemingly out of this world, dwelling in a place where names still need to be given. And yet these odd semblances suddenly turn into “art” through an act of naming, driven by a restless urge to appropriate. (Would it be possible to turn them outside in?) So tell me, if it weren’t for the label, what would these images be? Mere pastimes, activities, magical instruments – rituals perhaps?

⌘

In 1922, a pioneering study was published titled Artistry of the Mentally Ill (Bildnerei der Geisteskranken), which made its author, Hans Prinzhorn, quickly rise to fame. Prinzhorn had studied art history and singing, followed by medicine and psychiatry. He started his career at the Psychiatric Clinic in Heidelberg, where he got inspired by the director’s small collection of pictures made by his patients. Over the following years, Prinzhorn would visit psychiatric institutions in several European countries, collecting over 5,000 images that would also come to illustrate his bestseller. Where these pictures had previously been considered as odd curiosities, Prinzhorn saw them as symptomatic of a deeply human creative urge that is also to be found in children’s drawings or tribal art. Madness and genius, he writes, are connected by a rich and flourishing borderland. More interestingly, he made parallels with the expressionistic art movement that was emerging at that time. The expressionists, so Prinzhorn believed, were holding a mirror against the psychopathology of e ver yday life . A schizophrenic age required schizophrenic forms of art.

⌘

Artistry of the Mentally Ill had a lasting influence on the young Jean Dubuffet, the artist who famously coined the term art brut. Just in the same way as supposedly “primitive” art left its mark on modernist movements such as expressionism, cubism and surrealism, Dubuffet was struck by the spontaneity, directness and purity that is so peculiar to the art of children and so difficult to replicate in a later stage of life. As Nietzsche wrote:

Man’s maturity: to have regained the seriousness that he had as a child at play. Only after the Second World War did Dubuffet start collecting works by asylum inmates, and putting them on display in galleries (the entire collection is now housed in Lausanne, Switzerland). The anti-intellectual and anti-bourgeois character of psychotic art offered Dubuffet just the kind of artist statement that he had been longing for. It wasn’t until 1972 that art brut was given the English translation “outsider art” by art critic Roger Cardinal. But the actual meaning of brut is not that easy to translate. Perhaps the most interesting clue leads us back to Dubuffet’s earlier occupation in the wine business of his parents, where brut stand for only the best and purest champagne.

(Can you imagine how that tastes like?)

⌘

To tell the truth, the Outsider (also called Stranger) has always lived in our house but never felt at home. We must have let him in, for it is not his custom to go where he’s not wanted. God knows how long he’s been staying here and we haven’t even asked for his name. It is quite possible that he’s been hiding; far more likely is that he’s simply been neglected, forgotten or suppressed all this time. But he has never really left us, and surely never will.

– Pieter Vermeulen, April 2017

Warre Mulder and Tom Poelmans, DE HELD ZWEMT ALTIJD STROOMOPWAARTS, 2017, installation view, DMW Art Space, Antwerp

Warre Mulder and Tom Poelmans, DE HELD ZWEMT ALTIJD STROOMOPWAARTS, 2017, installation view, DMW Art Space, Antwerp

Warre Mulder and Tom Poelmans, DE HELD ZWEMT ALTIJD STROOMOPWAARTS, 2017, installation view, DMW Art Space, Antwerp

Warre Mulder and Tom Poelmans, DE HELD ZWEMT ALTIJD STROOMOPWAARTS, 2017, installation view, DMW Art Space, Antwerp

Warre Mulder and Tom Poelmans, DE HELD ZWEMT ALTIJD STROOMOPWAARTS, 2017, installation view, DMW Art Space, Antwerp

Warre Mulder and Tom Poelmans, DE HELD ZWEMT ALTIJD STROOMOPWAARTS, 2017, installation view, DMW Art Space, Antwerp

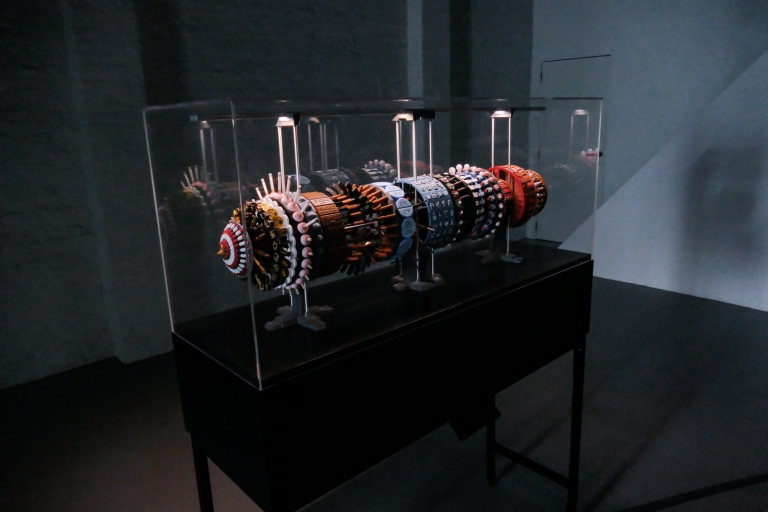

Warre Mulder, It takes spirit to know how to dance, it takes a monkey to get into trance, 2017, ceramics, wood, epoxy and paint, 73 x 26.7 x 17.6 cm

Warre Mulder, Intuïtie leidt de weg, 2016, wood, paint and epoxy, 190 x 70 x 50 cm

Warre Mulder and Tom Poelmans, DE HELD ZWEMT ALTIJD STROOMOPWAARTS, 2017, installation view, DMW Art Space, Antwerp

Warre Mulder and Tom Poelmans, DE HELD ZWEMT ALTIJD STROOMOPWAARTS, 2017, installation view, DMW Art Space, Antwerp

Warre Mulder and Tom Poelmans, DE HELD ZWEMT ALTIJD STROOMOPWAARTS, 2017, installation view, DMW Art Space, Antwerp

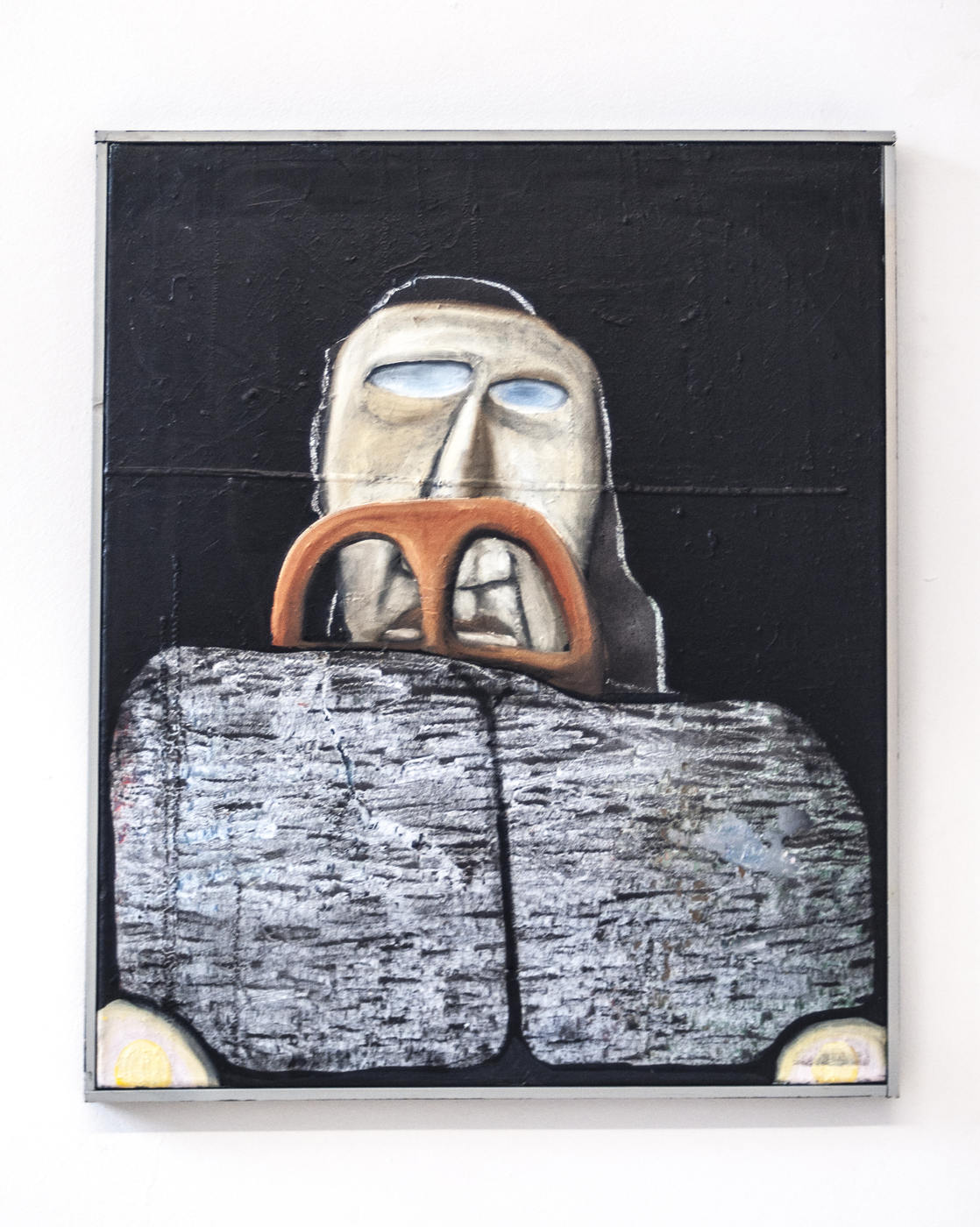

Tom Poelmans, Volg de richting van de weg, 2017, mixed media, 62 x 51 cm

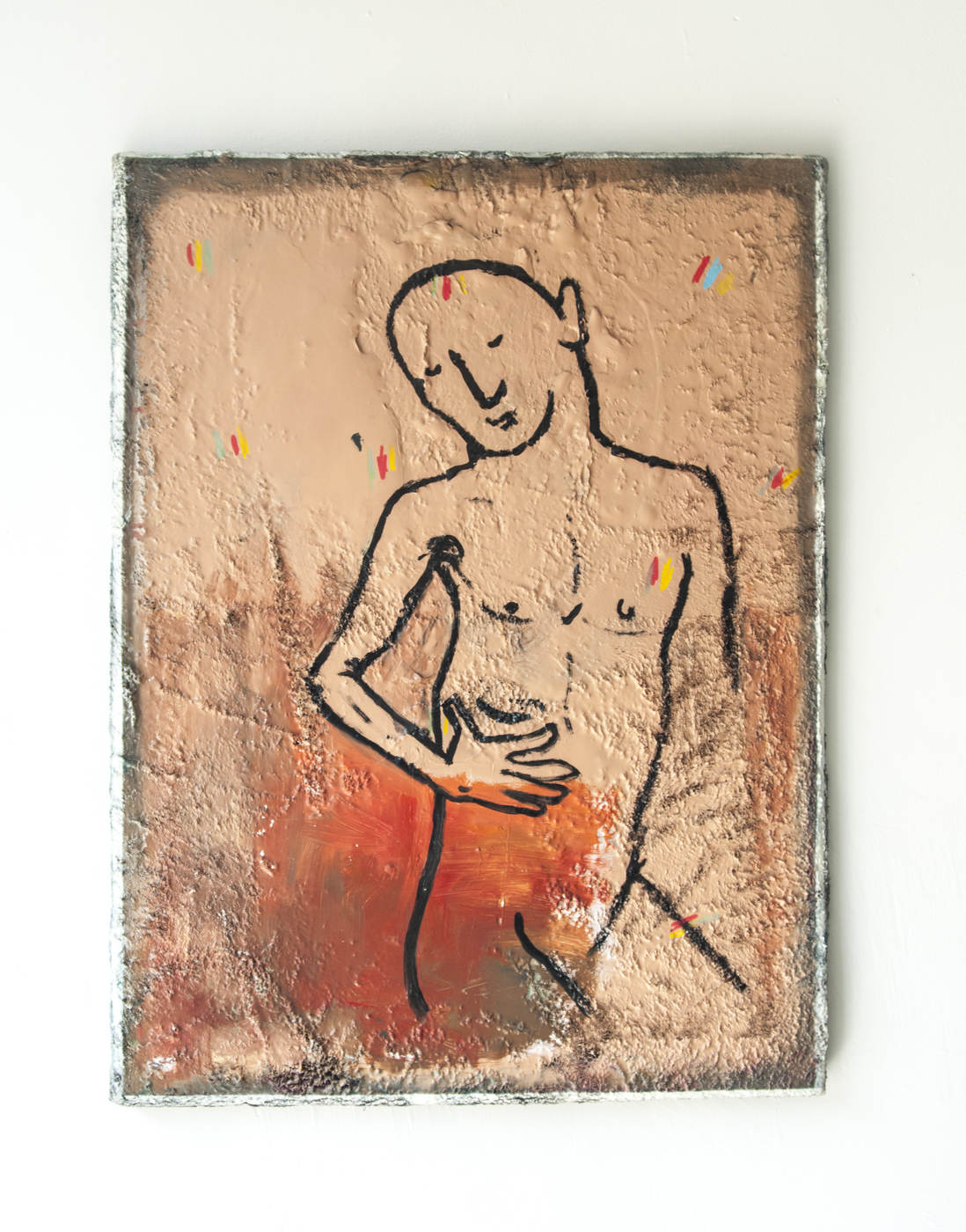

Tom Poelmans, The Wanderer, 2017, mixed media, 30 x 40 cm

Warre Mulder, Echo sapiens, 2017, wood, paint and epoxy, 56.5 x 17 x 18 cm

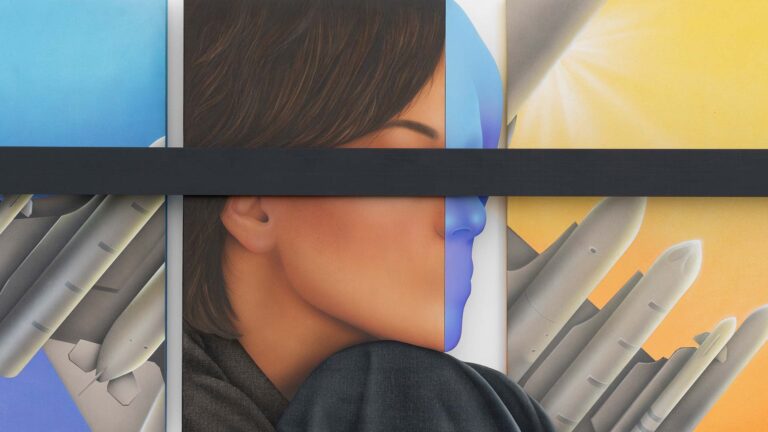

Tom Poelmans, Prince of Peace, 2017, mixed media, 100 x 80 cm

Tom Poelmans, Christ, 2013, mixed media, 80 x 61 cm