Reference or Translation?

Throughout 2015, on the occasion of its 25th anniversary, Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art examined its history, dedicating its ground-floor gallery to a series of commissioned presentations by a select group of contemporary artists. Each participant has created an image-based work that analyzes certain sediments of contemporary art history. In this essay, previously published in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition series, Witte de With curator Samuel Saelemakers reflects on the project.

“The image of art that Witte de With disseminates is a universal and autonomous one. It is a dissemination that should not prevent the construction of a framework which can tell us, for example, something about the glamor of art and its capacity for communication, about art from beyond Europe or North America, or about the terror of current events.”

The above statement is taken from the introductory essay in The Lectures, published in 1991 following Witte de With’s first year of operation. This current publication appears following the institution’s twenty-fifth anniversary. As such, the question begs to be asked: are the subjects of autonomy and universalism or critical reflections on the global dissemination and power of art still as present today as they were in 1990?

The ambition to offer a framework from which the world can be read through the lens of art has remained core to Witte de With’s program. With In Light Of 25 Years, this framework, in a way, has been brought into physical existence. Not quite a blank canvas but rather a picture frame or a window, the luminous display case, which hosted ten consecutive new works by a roster of contemporary artists, delineated a field of reflection. Made for, from, and in the present, these new works always imply the past as well as the future.

The participants were invited based on a number of qualities present in their respective practices, ranging from the ability to transform research into image to the skill of combining visual seduction with conceptual rigor. The project was as simple as it was perhaps self-reflexive: to invite nine participants to create a new work departing from a reference of their choosing, selected from the institution’s archive. Operating between carte blanche and constraint, the invited artists all elegantly maneuvered through the pitfalls of referentiality, institutional critique, pastiche or imitation, and brazen declarations of indebtedness or admiration.

Referentiality is one of those ‘tendencies’ that contemporary art is often accused of. How autonomous indeed can art ever be? Twenty-five years of attempting and Witte de With still has not produced any final answer. But then, what exactly is wrong with referencing? In academia, the right reference, more often than not, makes or breaks a thesis thought to be innovative. Every artist steals, but the art lies in knowing how to steal without getting caught, or so the platitude goes. Throughout 2015 Witte de With has opened up its vaults for invited thieves and their conspirators.

It seems in hindsight that many participants found the most lustrous treasures in the first half of the 1990s. Amongst the nine participants, more than half chose to create their work departing from or in reference to exhibitions from those formative years. Strangely enough, it is also only in retrospect that the concept of the canon comes to the fore when talking about the project. While it was unfolding, all we witnessed were subjective readings and interpretations, preferences and tastes. But then a canon is of course always only constituted retroactively.

If museums can be conceived as canon generators, Witte de With never set out to establish a dominant body of work: its definition as a center for contemporary art – or a so-called presentation institution to use Dutch cultural policy jargon – precisely aims to differentiate it from museums, as well as from commercial galleries. However, the rejection of certain dominant movements or extra-artistic criteria always also entails affirmative stances. The canon paradoxically often consists of counter-canonical artistic positions that, lately even at astounding speed, are recuperated by those norms it precisely sought to unseat. It is the contradictory fate of many protagonists of the avant-gardes. Since 1990, it seems that the concepts of avant-garde and canon have been hollowed out or, to use a more positive wording, enlarged or diversified in their meaning. In an irreversibly globalized and logarithmically connected world it seems there is space nor time left for a canon to be established, let alone for an avant-garde or counter-canon to be developed.

What does it mean to say the disseminated image of art is universal and autonomous in a world caught between supposed ontological flatness – ‘everywhere is anywhere is anything is everything’, to quote Douglas Coupland – and tribal excess? Is referentiality all that is left in a hyper-connected world?

Perhaps translation could serve as a more effective term used to avoid the issues referencing brings out. The translator is often treated harshly, located somewhere between traitor and freeloader. However, looking at the works documented in this publication, it becomes clear that it takes a good artist to make a good translation. Rather than directly referencing it, they each focused on a theme or motif present in the delineated frame of projects and created a new translation of these universal-autonomous-glamorous-current themes. If the translator is he who gives voice to something that already exists in another language, the artist is a translator speaking only their own tongue. As such, every artist’s contribution to In Light Of 25 Years showed the ongoing need to translate and interpret through art the happenings of the world.

–Samuel Saelemakers

Mahony

Exhibition title: Safe Harbour

Date: January 27 – March 1, 2015

Photography: Cassander Eeftinck-Schattenkerk

“A geopolitical site of frustrated proximity”, is how French-Moroccan artist Yto Barrada described the Strait of Gibraltar when interviewed by philosopher Nadia Tazi in the publication A Life Full Of Holes. The Strait Project. Barrada’s eponymous solo exhibition at Witte de With (2004) showed her ongoing photographic series portraying the Strait – the main gateway for northbound immigrants – and the impact of this fault line upon the lives of a generation of Moroccans, who have, in Barrada’s words again, “grown up facing this troubled space which manages to be at once physical, symbolic, historical, and intimately personal.”

For their work Safe Harbour, artist collective Mahony not only respond to Barrada’s work, but also to the continuing urgency of migration and border conflicts in Europe, through the inclusion of a digital image, blankets, and a poster as part of their display.

The image Mahony produced is that of a bridge, similar to the one found on the back of each Euro banknote – fictitious and in the style of a particular historical architectural period, which the artists used like a watermark on one side of the installation. The 500 Euro bill, different to smaller quantities, is adorned with a modern bridge which spans a greater distance, implying, according to the artists, that this largest sum, this biggest bridge, “will take you furthest;” that “bridges are a symbol for connecting places or the freedom to travel.” “By opening up the borders within the European Union, the outer European borders get reinforced. Europe today presents itself as an open, international and democratic space, but freedom of travel is still an issue.”

The second element Mahony folded into the installation were felt blankets, often seen in photographs of humanitarian or military operations in areas of conflict; not unlike moving or packing blankets purchased online through military suppliers. Mahony’s blankets are embellished with embroidered depictions of ancient Greek gods, such as Athena, Hera, and Minerva, whose names have been used for various military missions undertaken by Frontex, the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union. One of the blankets, hung over the lightbox, carries the cut-out sentence “There is no need to be modern” by Walter D. Mignolo, referring to modernity not as an ontological unfolding of history, but the hegemonic narrative of Western civilization.

A historical poster of The Truth about the Colonies, the counter exhibition to the 1931 Paris Colonial Exhibition, was the final touch to be embedded in the installation. The six-month exhibition celebrated French colonization by displaying colonial possessions and demonstrating its economic success. The French government also brought people from their colonies to Paris and forced them to create native arts and crafts, and to perform ceremonies in reproductions of their huts or temples. The small counter-exhibition was organized by the Communist Party in alliance with the Surrealists and other anti-colonial groups and was held in a Parisian annex of the Maison des Syndicats. Compared to some 33 million visitors that came from around the world to see the Paris Colonial Exhibition, the counter-exhibition attracted only 5000 visitors in eight months.

Mahony, Safe Harbour, 2015 (detail)

Mahony, Safe Harbour, 2015 (detail)

Mahony, Safe Harbour, 2015 (detail)

Freek Wambacq

Exhibition title: Cheval au galop avant Muybridge, Cheval au galop après Muybridge, Cheval au galop après Broodthaers, Cheval dansant le hula

Date: March 3 – April 5, 2015

Photography: Kristien Daem

Freek Wambacq draws connections between photographer Eadweard Muybridge, artist and poet Marcel Broodthaers, cinematic sound effects, and the Polynesian hula dance. His departure point Cheval au galop, Cheval au galop avant Muybridge, and Cheval au galop après Muybridge (1973-1974), a work by Broodthaers, was included in Still: A Novel, an exhibition about the origins of cinema and photography, and their influence on the visual arts that took place at Witte de With (1996).

Broodthaers’ humorous triptych of drawings referred to the mocking cartoons which the original publication of Animal Locomotion (1872-1885) by Muybridge provoked. These photographic studies of a running horse brought to light the fact that the human eye only sees the resultant of a series of movements: although we perceive the four legs of a galloping horse to be suspended in the air all at once, in reality this never occurs. Thus, Muybridge’s photographs show more than the eye can see and as such enlarge our perception of the world.

Wambacq takes up Broodthaers’ nod to the deceiving nature of imagery, as laid bare by Muybridge, creating four near-identical ink drawings of a nude woman in a crouched position, which were then scanned and enlarged. Wambacq’s female figure was inspired by a found vintage image of a hula dancer who is usually represented wearing a coconut bra, but who has now taken off this stereotypical attribute and positioned it atop the table standing in front of her. She daringly stares out from the picture plane.

In the tradition of Foley, a range of live sound effects originally developed for live broadcasts of radio drama in the early 1920s, a galloping horse is evoked using two halves of a coconut. Cheekily, and quietly, Wambacq makes the horses on the tables dance while the hula girl watches.

Freek Wambacq, Cheval au galop avant Muybridge, Cheval au galop après Muybridge, Cheval au galop après Broodthaers, Cheval dansant le hula, 2015

Freek Wambacq, Cheval au galop avant Muybridge, Cheval au galop après Muybridge, Cheval au galop après Broodthaers, Cheval dansant le hula, 2015 (detail)

Wineke Gartz

Exhibition title: 000 VA Auroral Blue

Date: April 7 – May 10, 2015

Photography: Cassander Eeftinck-Schattenkerk

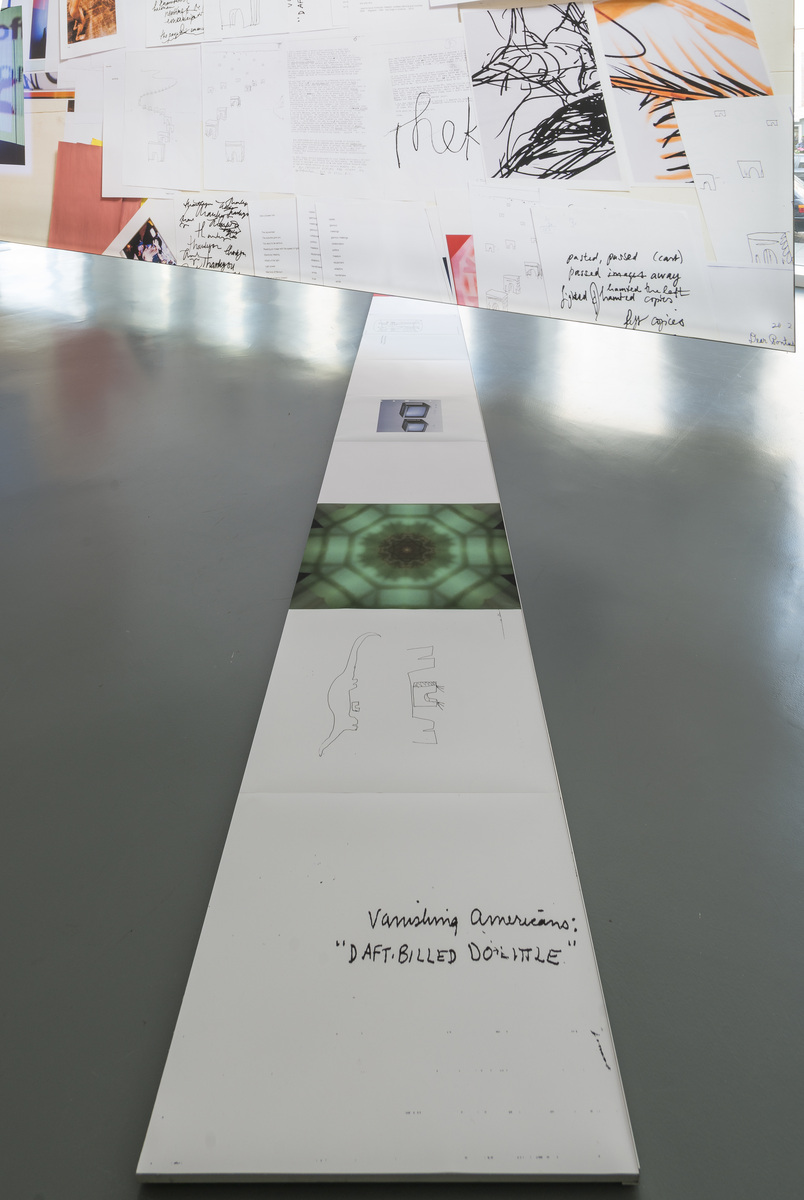

Combining selected archival documents and images of her previous work, including the body of work American Pain (2009 – ongoing), Wineke Gartz – known for her work that relates to psychology, illusion and perception, art, and mass media – transforms parts of the Witte de With archive into an image stream, rather than an organized system. In her two collages, auras, dissolves, transparencies and layering add up to dreamlike and haunting images.

The casino slot machines seen on the upper half of one of her two collages illustrate the artist’s fascination with the U.S., its consumer culture and commodified notion of happiness, a fascination she shares with artist Dan Graham, a long-term conversation partner of Gartz. He is also present is this work through reproduced stills from his iconic video essay Rock My Religion (1982–1984), and his performance Body Press (1972), in which we see him holding a camera. Offering an overload of imagery, in line with the busy street it looks out on, here, Gartz mostly uses photographs she took while installing her previous video installations, creating portals or escape routes from the feverish process of creation. A centrally placed video-still taken from the recording of the performance Red Light, Poses (2009) shows Gartz’s body turn into a surreal animal-like object, bathing in red and gold light.

With her second collage, Gartz takes a different approach and presents archival letters and drawings by artist Paul Thek, to whom Witte de With dedicated a solo exhibition (1995), alongside written lists and drawings by Gartz herself. She strongly relates to Thek’s practice, which she sees as a form of exorcism, dealing with the labyrinths of spirituality, sexuality and technological progress.

Through a process of digitizing physical collages spread out on her studio floor, Gartz addresses the specificities of the digital and its impact on imagery. Her practice, much like Witte de With’s own archival history since the 1990’s, evolved along the increasingly oppositional dynamic between the hard-copy and the digital.

Wineke Gartz, 000 VA Auroral Blue, 2015

Wineke Gartz, 000 VA Auroral Blue, 2015

Wineke Gartz, 000 VA Auroral Blue, 2015 (detail)

Wineke Gartz, 000 VA Auroral Blue, 2015 (detail)

Özlem Altin

Exhibition title: No story, no

Date: June 9 – July 12, 2015

Photography: Cassander Eeftinck-Schattenkerk

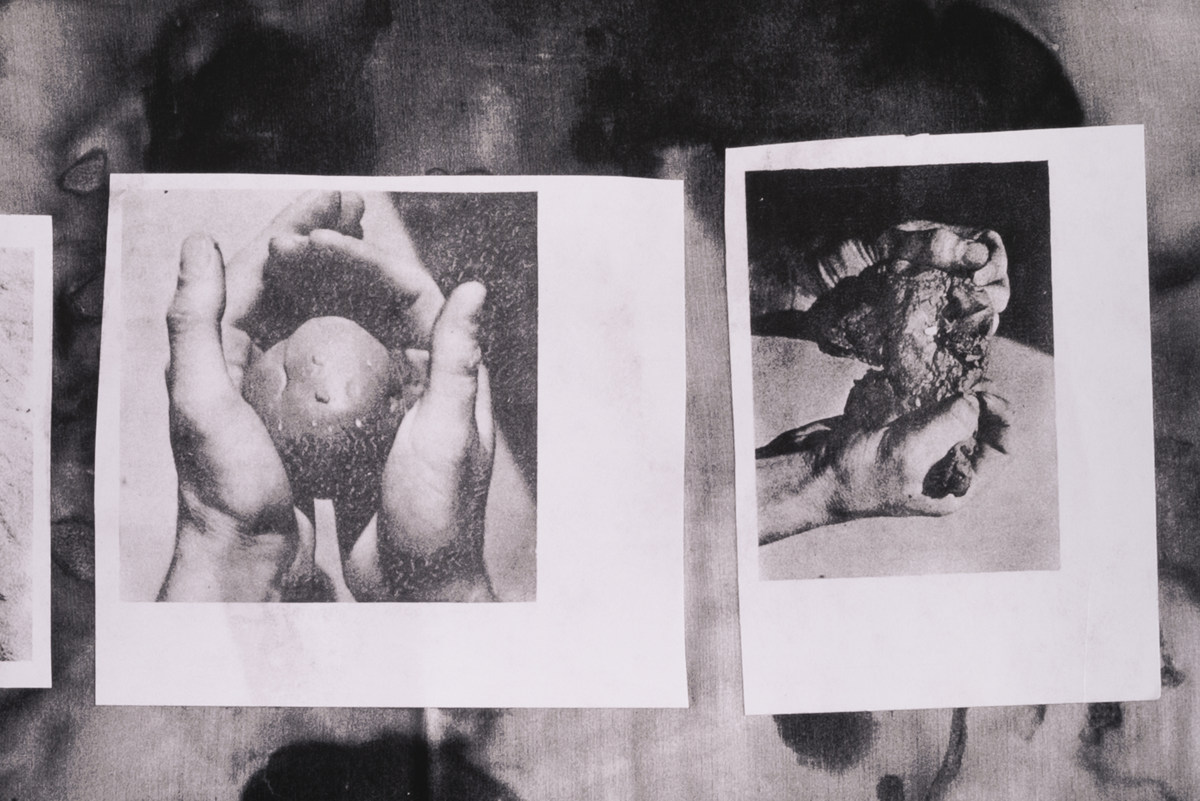

For her new work, Özlem Altın was instantly drawn to Pas d’histoire, Pas d’histoire (No Story, No History) (1994), the first large-scale solo exhibition by Belgian artist Joëlle Tuerlinckx. She asked herself how to make Tuerlinckx’s work resonate with her own and whether this personal resonance could establish a platform that allows new readings on how stories and histories are created and displayed. Altın shares with Tuerlinckx a great interest in what she calls ‘suspended objects and gestures’.

Much like Pas d’histoire, Pas d’histoire, Altın’s work No story, no consists of an open-ended constellation of image and text. Depicting both human and artificial hands in various stages of suspended movement, and manipulating different objects, the sense of these gestures remains ambiguous. French art historian Henri Focillon wrote in his essay In Praise of Hands (1934): “Through his hands man establishes contact with the austerity of thought.” And indeed, here Altın uses hands as a means to work through her thoughts, drawing from multiple sources to create two enigmatic digital collages.

Özlem Altin, No story, no, 2015

Özlem Altin, No story, no, 2015

Özlem Altin, No story, no, 2015 (detail)

Özlem Altin, No story, no, 2015 (detail)

Xu Zhen

Exhibition title: One of Us Is On the Wrong Side of History!

Date: July 14 – August 16, 2015

Photography: Cassander Eeftinck-Schattenkerk

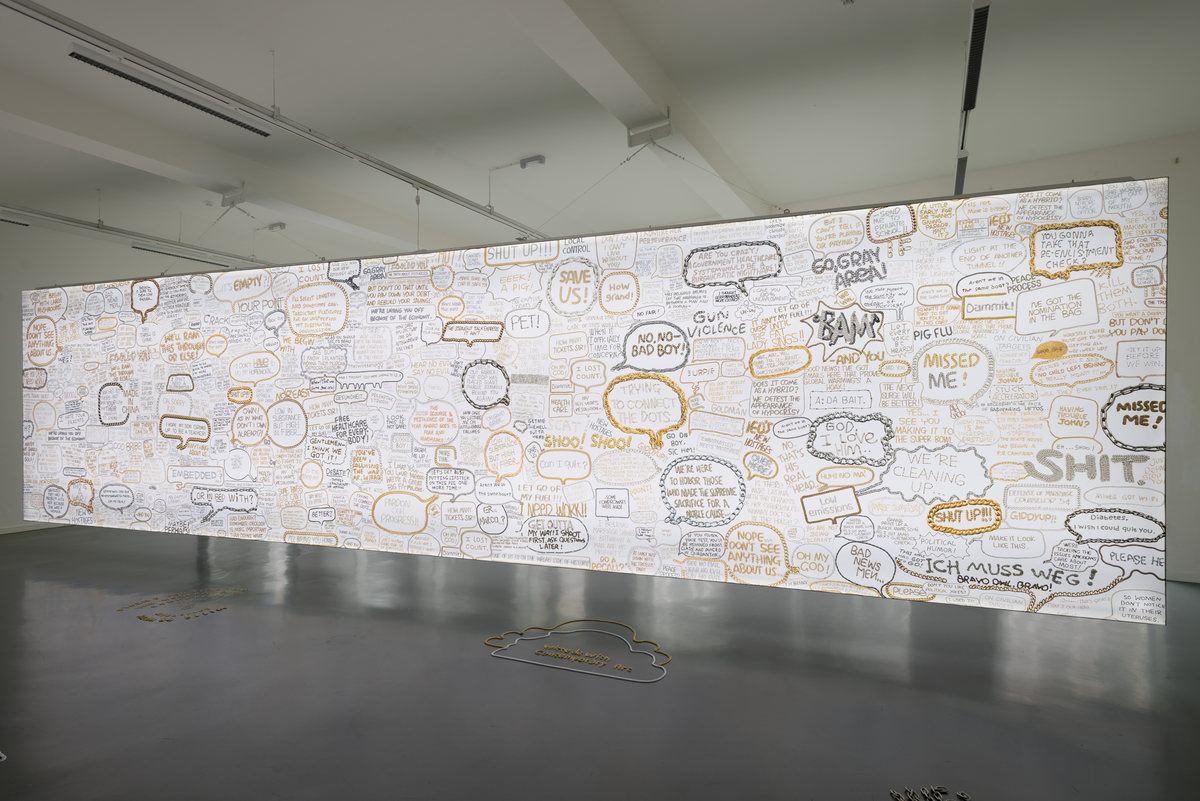

What does visual identity say about exhibitions and the way in which they are mediated to the public?

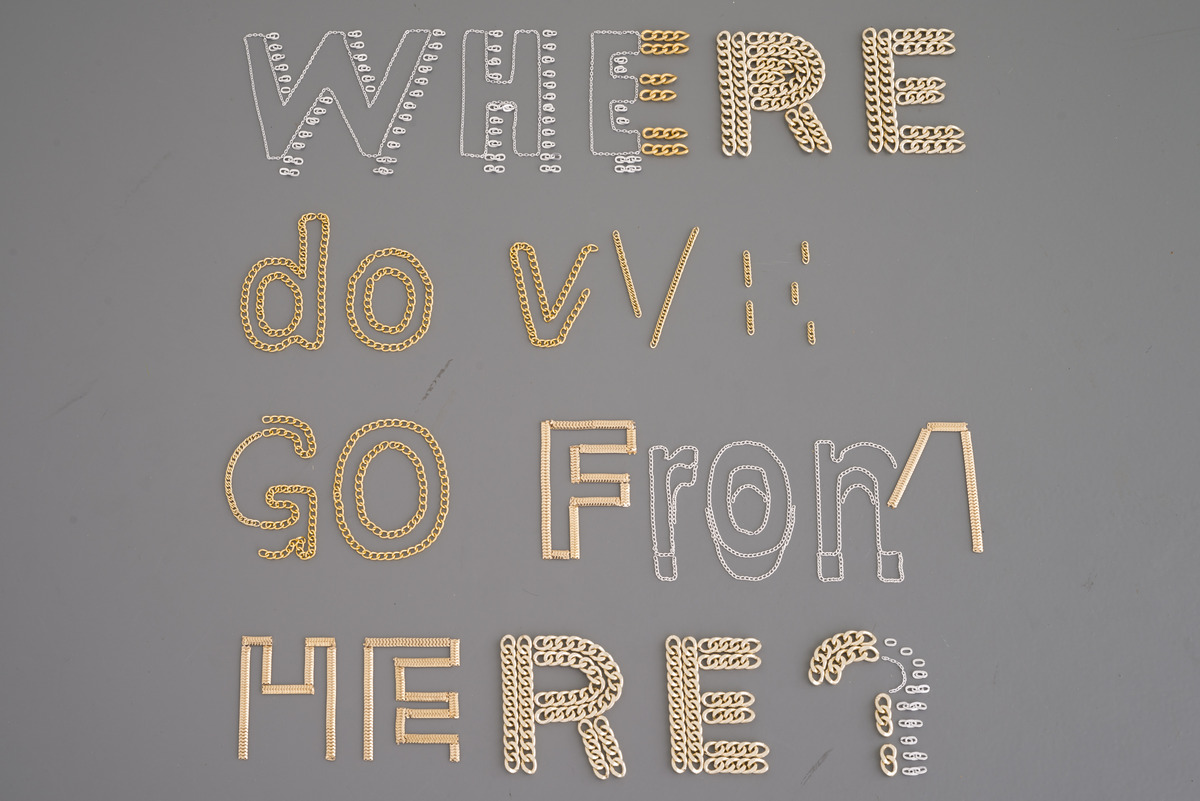

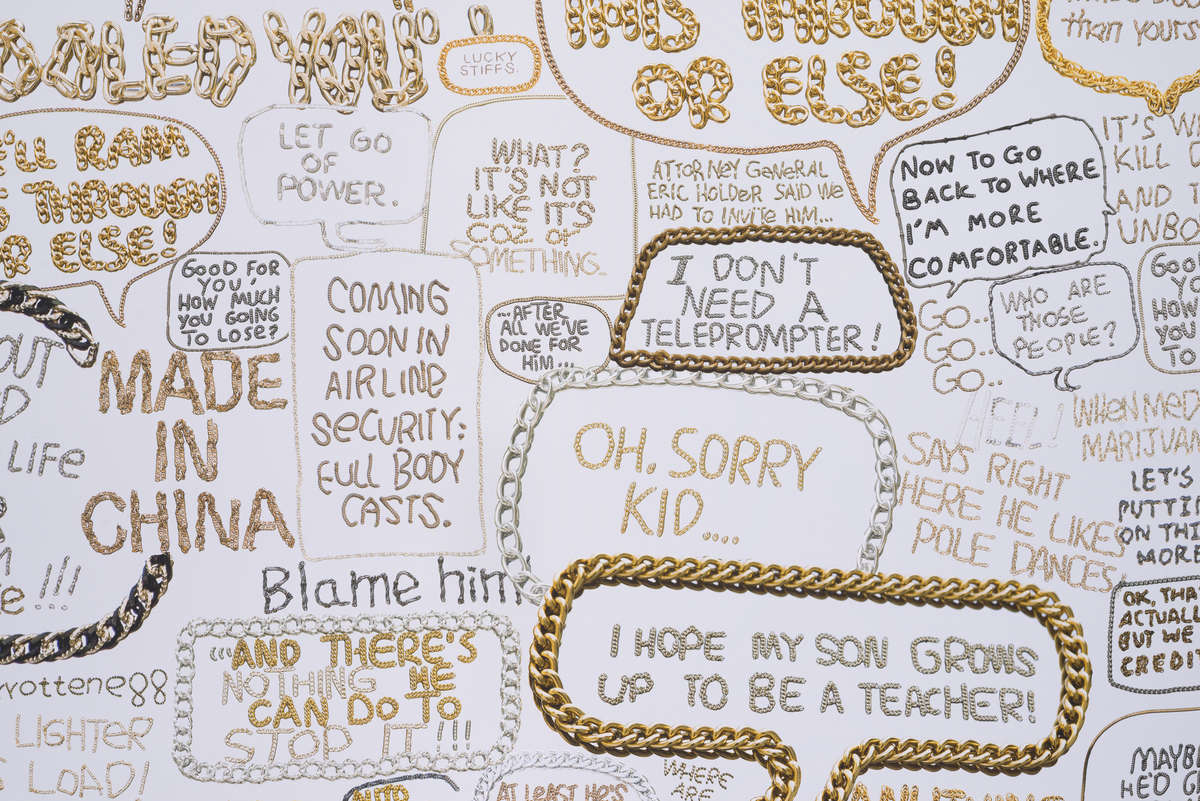

In the same vein as his Metal Language series (2012), Xu Zhen first fills the lightbox with sentences from found political caricatures and text fragments such as “Pardon our Progress” or “Save Us”, then choosing to focus on the graphics of Witte de With’s past exhibitions and its archive of posters.

With One of Us Is On the Wrong Side of History!, he extracts fonts and layouts from their original context and reproduces them using metal chains laid out on the floor, revealing a sprawling visual poem made up of fragments and traces of voices past, including titles and logos of the institution’s programs and exhibitions: Morality, Stories and Situations, Occupying Space, Where do we go from here?

Shimmering like jewels but weighing down on the physical foundation of the institution, the choice of metal shackles reflects the ambiguity of history itself: is it a treasure or a burden?

Xu Zhen, One of Us Is On the Wrong Side of History!, 2015

Xu Zhen, One of Us Is On the Wrong Side of History!, 2015

Xu Zhen, One of Us Is On the Wrong Side of History!, 2015 (detail)

Xu Zhen, One of Us Is On the Wrong Side of History!, 2015 (detail)

Zin Taylor

Exhibition title: A Segment of Translation (F. Kiesler’s Mind Form)

Date: August 18 – September 23, 2015

Photography: Cassander Eeftinck-Schattenkerk

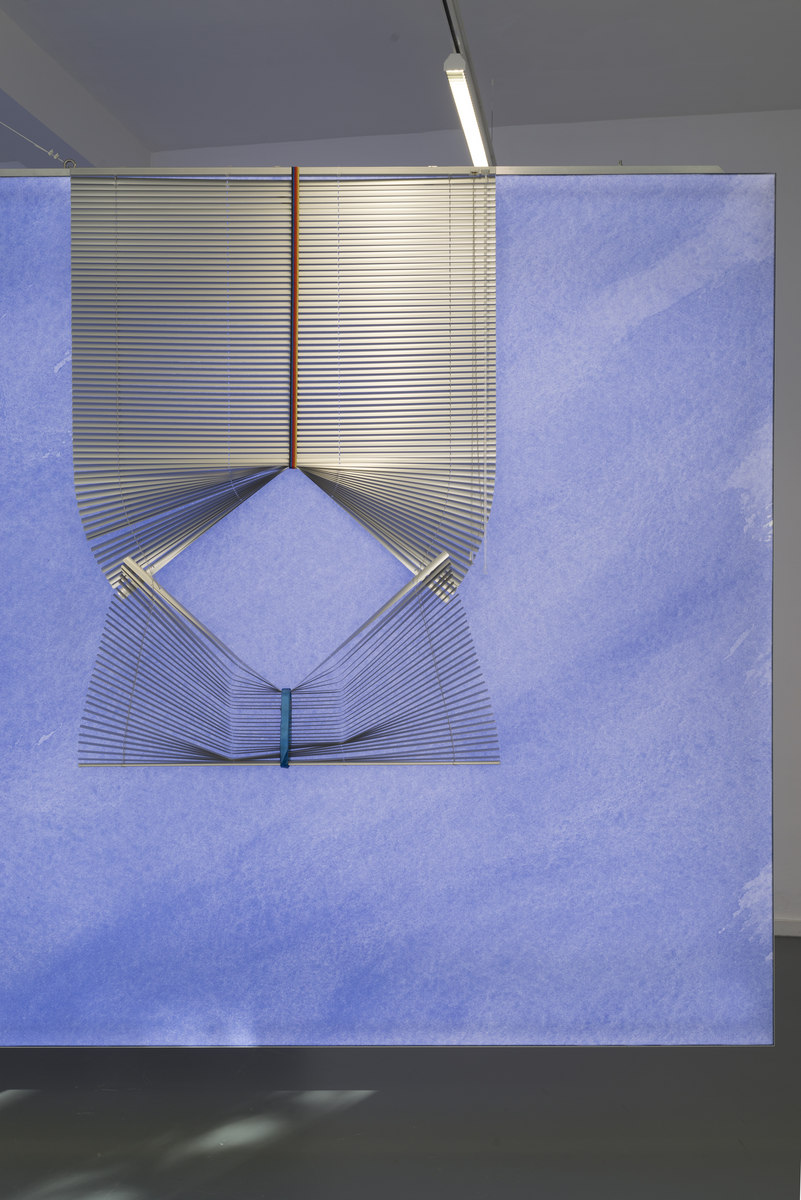

A Segment of Translation (F. Kiesler’s Mind Form) stems from Zin Taylor’s extensive research into the work and writing of architect, theoretician, and sculptor Frederick Kiesler (1890-1965), whose first retrospective in Europe was held at Witte de With in 1996.

Taylor approaches the lightbox as an architectural element conceived in close proximity to Kiesler’s thinking. Kiesler used the word ‘organic’ to describe his aim for architecture, where a form emerges from a creative consciousness to be translated into concrete existence. Taylor describes his practice in a similar way, as a process where thoughts about a subject are translated into forms about a subject, where abstraction and phenomenology participate as tools in a narrative development of form. The two sides of the luminous display together form a permeable wall, a skin that touches both an interior and exterior space. Building a space for thoughts to exist within, the wall divides the private thought from the public form – a membrane that collects these two opposing elements.

The image of the ‘inner space’ can be seen as a cave for contemplation. The Endless House (1950-61), arguably Kiesler’s most important work, is the result of his lifelong scrutiny of the conventions of modern architecture. It existed as an idea, materialized only as scale models and sketches, making it a house built from thought, rather than stones. The entire house exists as one form, endlessly flowing, or as Kiesler wrote: “like the human body – there is no beginning and no end to it.” This side of Taylor’s work can be seen as a hypothetical rendering of the inside of the Endless House, the structure of which in many ways resembles that of a yurt, a type of mobile housing unit originating from the Middle East and North Africa that was adopted by American west coast hippies and communes as a home for their ideological activities. This correlation brought Taylor to the idea that alternate ideas take on alternate forms, and alternate forms have the ability to generate alternate ideas. Of the many characters on the front of the wall, one, on the far right, is an illustrated rendition of Mr. Natural, a character by cartoonist Robert Crumb that satirically embodies the hippy movement and its eventual ideological demise.

Of particular influence for Taylor were a series of poems written by Kiesler that were published in the Witte de With publication Cahier #6. Taylor interprets these as words Kiesler immediately put to paper upon waking from a hallucinogenic dream-episode he underwent in 1962. Although the Endless House was already completed as an idea by then, Taylor asks: could these poems have taken form within the space created by the organic house? He sees Kiesler’s poetry occurring as the result of the Endless House, that piece of strange architecture presenting a mental opportunity for an extended form of abstraction to take place. In other words, the narrative of the poems occurred within the space made for it by the thought of the Endless House: thoughts within thoughts.

Zin Taylor, A Segment of Translation (F. Kiesler’s Mind Form), 2015

Zin Taylor, A Segment of Translation (F. Kiesler’s Mind Form), 2015

Zin Taylor, A Segment of Translation (F. Kiesler’s Mind Form), 2015 (detail)

Zin Taylor, A Segment of Translation (F. Kiesler’s Mind Form), 2015 (detail)

Camille Henrot

Exhibition title: The Beaver Moon

Date: September 29 – October 25, 2015

Photography: Cassander Eeftinck-Schattenkerk

Known for blurring the traditionally hierarchical categories of art history in her videos and animated films, which combine drawn art, music and occasionally scratched or reworked cinematic images, Camille Henrot was immediately drawn to Michelangelo Pistoletto e la fotografia (1993). Pistoletto’s canonical series of works used mirrors and photography to create trompe l’oeils where the distinction between physical objects and representations is blurred. In addition, she was influenced by Bild Archive (2003), an exhibition of Ulrike Ottinger’s video works in which a universe of strange characters unfolds, inspired by countercultures and questioning social norms and morals.

For The Beaver Moon, Henrot drew from her background in animation and created two human-like characters which she staged as if involved in the domestic activities of maintenance and cleaning. Existing somewhere between the realms of male and female, human and bird, they are reminiscent of the Egyptian god Thoth, who has the body of a man and the head of an ibis, and who was the god of writing, science, and magic. These creatures act as the “care-keeper of the universe”, reminding us that exhibition spaces themselves are the homes of artworks, and sometimes of artists too.

Camille Henrot, The Beaver Moon, 2015

Camille Henrot, The Beaver Moon, 2015 (detail)

Camille Henrot, The Beaver Moon, 2015 (detail)

Germaine Kruip

Exhibition title: A Room, 4 Minutes

Date: October 27 – November 29, 2015

Photography: Cassander Eeftinck-Schattenkerk

Using time and space as her material and operating from within the tension between formal abstraction and lyrical spiritualism, Germaine Kruip creates a choreography of light and sound which repeats itself endlessly. With a predilection for ephemeral objects such as sound or fleeting experiences of time, Kruip – with a background in stage design – used the fixed display element of the lightbox not as a carrier for imagery and representation, but as a performative agent.

At the entrance of the exhibition space stands a clock that counts down from four minutes to zero; inside, another clock counts upwards from zero to four. The counting up and down is activated by the sound of hands clapping. This single clap of two hands is reminiscent of the clapperboard used in cinema. Once the clap is heard, the action begins. The light flicks on, then off again.

A Room, 4 Minutes not only refers to Kruip’s previous work A Room, 24 Hours, in which a lamp rotates 380 degrees over a time span of 24 hours, but also acts as a tribute to the work of artist David Lamelas, whose first retrospective exhibition in Europe, A New Refutation of Time (1997), took place at Witte de With. Kruip’s new work is inspired by Lamelas’ pieces such as Time as Activity (1969) which showed four minutes of recorded city scenery, shot at three different locations then shown in one exhibition space; or Two Modified Spaces (1967) in which the artist modified the exhibition space, creating a stage within a stage by use of light and wooden cubical frames. With A Room, 4 Minutes, Kruip, much like Lamelas, urges the spectator to become aware of the room they are in, the space they occupy, and the time they spend there.

Germaine Kruip, A Room, 4 Minutes, 2015

Germaine Kruip, A Room, 4 Minutes, 2015

Germaine Kruip, A Room, 4 Minutes, 2015 (detail)

Raimundas Malašauskas

Exhibition title: Whom we are looking at tonight?

Date: December 1, 2015 – January 17, 2016

Photography: Cassander Eeftinck-Schattenkerk

“All the children will go to sleep, adults will marvel at each other and at an invisible object in the future, asking each other “How do we know if we are still alive?”; The radio will be playing Marvin Gaye, who always sits on one of the shelves upstairs,1 and a blown up paper toy by Viktorija Rybakova will swirl around Jef Geys’ writings;2 It is 19933 and 2016 at once, or perhaps twice, in the same room, in the split gaze, like that film shot from the perspective of someone whose identity multiplies or changes half-way. “How many times you’ve been dead?” one may ask.” R.M.

1 On the first floor landing, gracing a window looking into Witte de With’s offices, stands a vinyl record of Marvin Gaye’s hit single What’s Going On (1971). The record has been standing there for over twenty years; the song is the hold music for Witte de With’s office phone line.

2 “The words I am writing are mirrored in the red balls on the imaginary Christmas tree which is not in my hotel room in Bredene aan Zee. They take shapes that even I can barely recognize: the word “black” is powdered with artificial snow, and “valid” rotates slowly round the tree’s green tip. “Division of labor” is reflected off the stomach of the pink-and-white mannequin onto the pale yellow fake straw before the words fade away between the ox and the ass. Mary’s blue cloak swallows up “working week” and “condensation,” and “demo” glides from one imitation pearl to the next.”

Jef Geys, What are we going to read tonight?, Cahier #2, Witte de With Publishers, 1994

3 The 1993 exhibition Wat eten wij vandaag? (What Are We Having for Dinner Today?) at Witte de With was associated with the fifth Architecture International Rotterdam manifestation, whose theme was the postwar residential areas built in Rotterdam’s Alexanderpolder neighborhood. Jef Geys’ project commented on the abstract way architects, urban planners and politicians tend to think about the urban environment.

By inviting nine families from Alexandepolder to contribute to his exhibition, Geys let the residents have their own say about the area they inhabit. The project was realized with the cooperation of the families Bast, Battes and Risse, De Bruin, Diepstraten, Groot and Van Halem, Roodbeen and Boode, Van Schouwen, Sevenhuijsen, and Verkade.

In the exhibition, the families presented photographs of their living rooms. Each evening, throughout the entire exhibition period, one of the nine participating families was filmed having dinner and broadcasted by the local television station.

Raimundas Malašauskas, Whom we are looking at tonight?, 2015

Raimundas Malašauskas, Whom we are looking at tonight?, 2015 (detail)