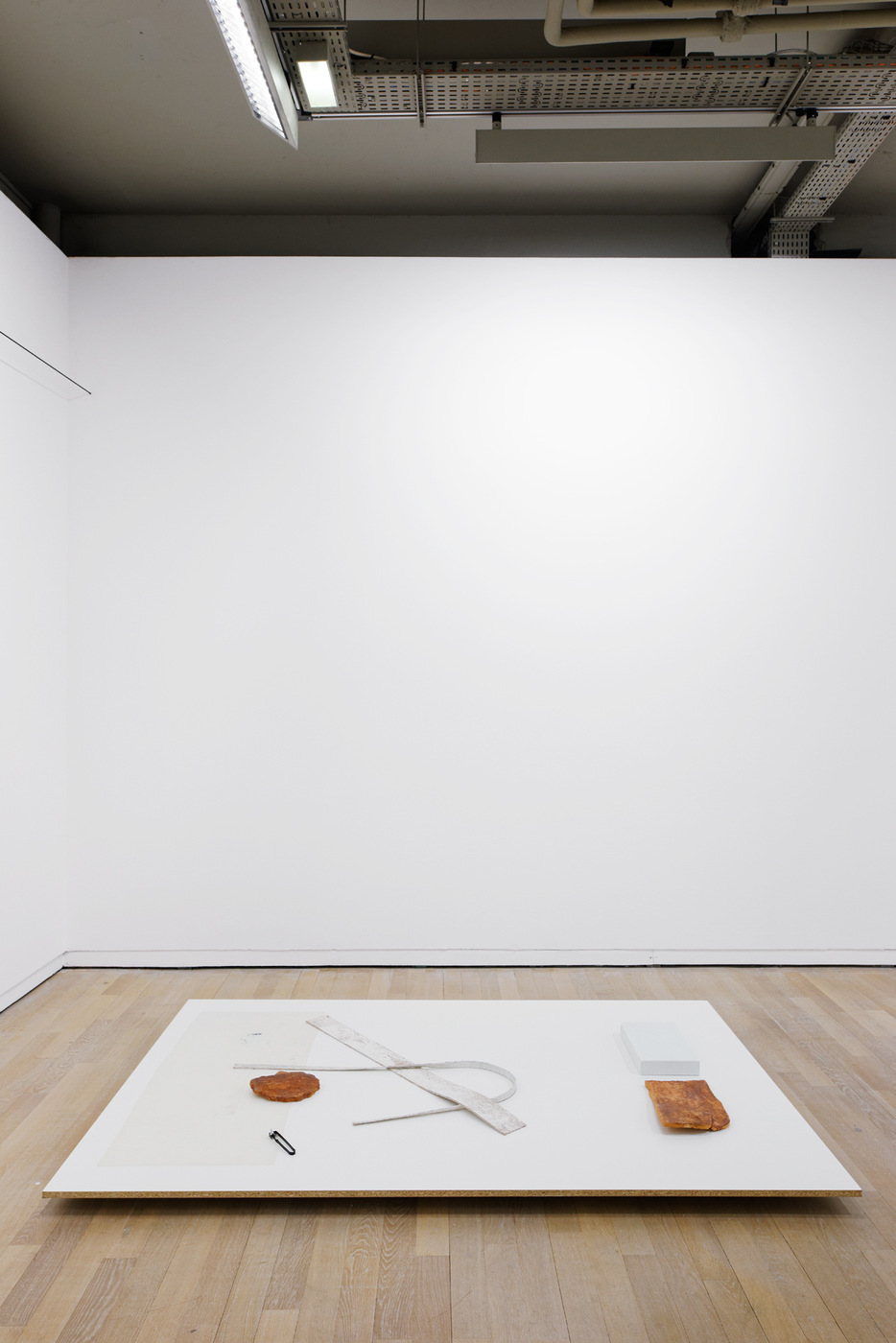

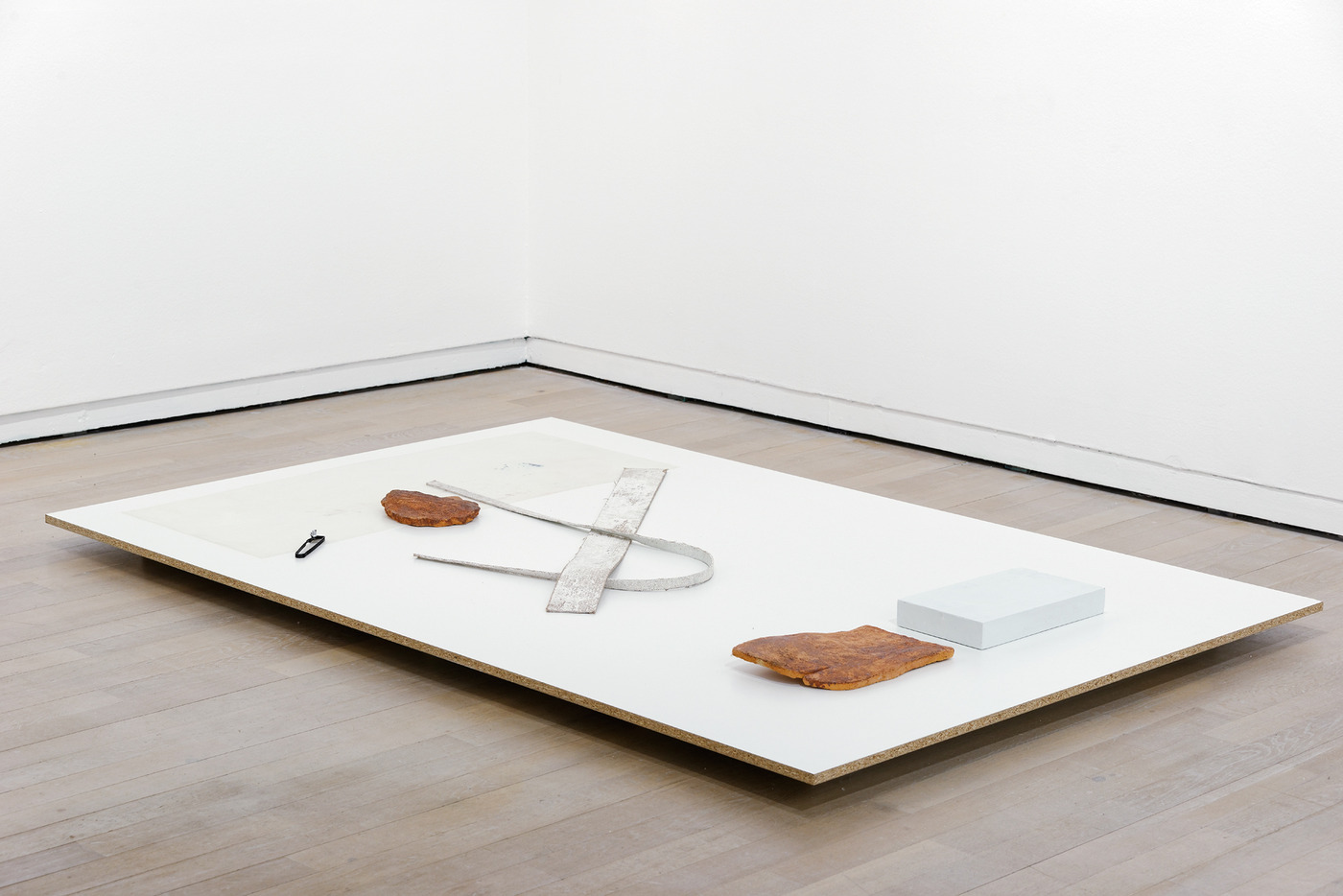

Artist: Sophie Bueno-Boutellier

Exhibition title: La Ritournelle du Peuple des Cuisines

Curated by: Dorothée Dupuis

Venue: Fondation d’entreprise Ricard, Paris, France

Date: May 23 – July 2, 2016

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Fondation d’entreprise Ricard

A series of gestures

Sophie Bueno-Boutellier is a painter and sculptor. Her installations combine ready-made objects with elements made from humble materials readily available in DIY shops. Her preferred medium is plaster, for its ease of use and its ability to create an instant, accurate reproduction of any shape and to soak up pigments. The shapes she creates are often cylinders and parallelepipeds of varying size and thickness, juxtaposed with casts of ordinary objects. She also uses plywood panels which she sometimes “dresses up” as other materials, such as fake marble and stone, using simple decorating techniques. She uses the same medium to build platforms to display elements together for her installations. These platforms of varying heights can be placed abutting a wall or free-standing, and are sometimes given a hint of neutral colour.

Her ready-mades are either purchases such as rolls of kitchen towel and electric cables, or found objects such as ceramic waste. For the present exhibition, she placed a special order for objects – in this instance, weavings based on drawings depicting swirls in liquids when they are stirred – from Alberto Ruiz, a craft weaver from Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca, renowned for the quality of his textile work.

Sophie Bueno-Boutellier also creates object-paintings by folding canvases prepared with gesso. Most of these paintings are of a size that reflects the fact that they are produced by hand, dependent on the artist’s body and physical abilities. In the exhibition, they take on twin roles, as elements of the installation and as quasi-transitional objects between the sculptures and the weavings, which are also paintings in their own way.

The way the various elements are staged in the gallery reflects the implementation of a series of intuitions and tests carried out in a studio setting to establish the place of each object within an overarching plan that is subject to development, explaining the artist’s initial intentions as regards the planned exhibition. Each installation is created based on a clear starting idea that constantly challenges artistic practice by reproducing, hijacking, and complexifying motifs and gestures in an ongoing cycle of construction, deconstruction, and reconstruction.

A practice in which the personal is context rather than subject

Sophie Bueno-Boutellier follows in the footsteps of women artists whose work is formalist in approach, who are determined not to give their male counterparts a monopoly on the universality of discourse, and who are well aware of the reductionism inherent in claims to identity. Her work should thus be read in the light of female sculptors and artists who openly profess their calling such as Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, and Lynda Benglis, or whose work is systematically minimalist such as Vera Molnar and Fernanda Gomes, assemblagist such as Isa Genzken, appropriationist such as Sherrie Levine, or conceptual such as Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and Tatiana Trouvé – who, like Bueno-Boutellier herself, is a graduate of the Villa Arson.

All these women artists are determined to plant their flag firmly in the field of post-minimalist practice, their only distinct style being that they are the direct result of modernity – and unashamedly so, fully aware as they are of the issues of production and reproduction at stake in shaping and influencing their creative processes.

Memory, affect, and sensuality are subjects close to Sophie Bueno-Boutellier’s heart: they can be read as intuitive, polysemic elements in her work without necessarily being reduced to the expression of womanhood – and if they are, it is to serve as reminders that womanhood is by no means a fundamental characteristic but rather an interplay of constructed connotations, albeit ones suffused with symbolic implications that play into the individual viewer’s aesthetic experience by calling on an entire cultural and vernacular background whose limits are clear to the artist, who nonetheless strives to reach beyond them

Clearing up certain misconceptions

The Refrain of the Kitchen People (1) is an essay in the visual arts that posits the gesture and the body as fundamental units of measurement in our perception of time and space and the construction of our relationship with our social, affective, and productive surroundings. Starting from the kitchen, understood as a defined domestic space with its own consecrated social and productive uses, Sophie Bueno-Boutellier creates a setting in which objects function as much as autonomous artistic creations as archetypes incorporated into a broader cultural fiction to have emerged from the artist’s imagination. The biographical component – the way she transfers productive gestures from the studio to the kitchen as she takes on her reproductive role as woman and mother – is here simply a clue intended to hint at the concrete origins of the decisions taken by the artist to shape the work during the production process. The partition/window that stands between open/closed and occupied/empty spaces as if in reference to women’s separate spaces, the works that move from the floor to the walls and onto plinths with a sort of Mediterranean nonchalance, the weavings produced by a man in a far distant country, the utensils for chopping, flattening, absorbing, holding, and sharing, are all concrete translations of age-old social and formal divisions, played out here in the medium of sculpture and installation.

At a key moment in our period in history when a crisis of humanism (2) is forcing our civilisations to define a new shared vision of the human being and the individual, Sophie Bueno-Boutellier’s art sheds opportune light on both the evolution ad the atavism of our relationship with our daily symbolic and gendered rituals. It posits the cultural not as a series of oppositions, but as the potential for an organic, intersectional relationship with our surroundings.

Dorothée Dupuis, May 2016.

1 : “The kitchen people” is a paraphrase from the title of an article by Luce Giard in volume two of L’Invention du quotidien [The Practice of Everyday Life], coedited with Michel de Certeau. Paris: Gallimard, 1980.

2 : Rosi Braidotti, The Posthuman, Polity Press, Cambridge, 2013, introduction.