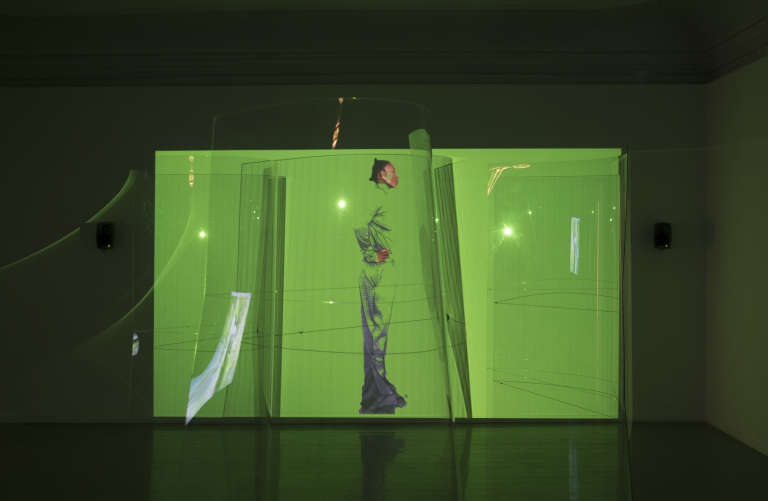

Artists: Tora Dalseng, Ane Graff, Anthea Hamilton, Mikael Øye Hegnar, Mirak Jamal, Nancy Lupo

Exhibition title: SELFLESSNESS

Venue: 1857, Olso, Norway

Date: April 5 – May 19, 2019

Photography: RH Studio, images copyright and courtesy of the artist and 1857, Oslo

Such is the nature of life, to engage the material world and incessantly incorporate its components, sorting among potential food, waste and fuel in order to maintain inward integrity. As the senses scan and register their environs, perceptions assemble into a unitary image-inary. In the human brain this flurry of cooperation typically takes about 200-500 milliseconds: the “nowness” of a perceptuo-motor unity. Cognition does not flow, but rather marches to syncopated rhythms that arise and subside in chunks of time.

Each sensory layer connects perception directly to brain-action. An outside observer might impute a principal representation or central control, but the internals of cognition are a bricolage of divergent processes. From the local chaos of their interactions there emerges – to the eye of the observer – a coherent pattern of behavior.

□□□

Ants are a non-visual superorganism who communicate indirectly through environmental stimuli, in what is termed stigmergy. This affords them an immediate sense of the social fabric, which makes them the world leaders in communal living. After being separated into a sub-colony, the most efficient nurses from one Lasius niger colony radically change their social status, and become more prone to foraging and less involved in nursing. The contrary happens in the remaining colony: formerly low-level nurses increase their nursing activity. The whole system even exhibits evidence of a configurational identity with a memory, since the nurses will return to their previous state when the social order is undone by returning the excised element back to the colony.

In the case of the ant colony we would – unlike that of the brain – readily admit that (i) its separate components are individuals and (ii) there is no center or localized self. Yet the whole behaves as a unit and for the observer it is as if there was a coordinating agent present at the center. Here emerges the selfless self: simple components give rise to a coherent global pattern that appears to have a central location where none is found, and yet it is essential as a level of interaction for the behavior of the whole unity.

———

selve, v.

rare.

intransitive (only G. M. Hopkins). To become and act as a unique self.

1880, G. M. Hopkins, Serm. & Devotional Writings (1959), 125: Nothing can exercise function and determination before it has a nature to ‘function’ and determine, to selve and instress, with.

Etymology: < self n.

———

The cognitive self is its own implementation: its history and its action are of one piece. What then can be said about its mode of relation with the environment? Ordinary life is necessarily one of situated agents, continually coming up with what to do faced with ongoing parallel activities in their various perceptuo-motor systems. This continual re-definition of what to do is not at all like a plan, stored in a repertoire of potential alternatives, but enormously dependent on contingency, improvisation, so much more flexible than planning.

Situatedness means that a cognitive entity has – by definition – a perspective. It does not relate to its environment independent of its location, heading, attitudes and history. Rather, it engages through the perspective established by its own constantly emerging properties and in terms of the role this running redefinition plays in the coherence of the entire system. This distributed dynamics is inseparable from the constitution of a world, consisting of the surplus of meaning and intentions carried by situated behavior. If the links to the physical environment are inevitable, the uniqueness of the cognitive self is this constant genesis of meaning. Or, to invert the description, the uniqueness of the cognitive self is this constitutive lack of signification that must be supplied faced with the permanent perturbations and breakdowns of the ongoing perceptuo-motor life. Cognition is action about what is missing, filling the fault from the perspective of a cognitive self.

“A complete life may be one ending in so full identification with the non-self that there is no self to die.”

– Bernard Berenson

The essential arbitrariness of our definitions of self, of organismic identity and individuality, is made all the more striking by considering the case of a moth. Here is a being that undergoes radical bodily change between egg and chrysalis, between pupa and winged insect; and yet the only time we say it dies is after the adult moth form stops moving its wings, despite the other metamorphoses that nonetheless preserved its genetic makeup. We might as easily have chosen to consider the transfer from egg to chrysalis or from chrysalis to moth as “death” – and construed the demobilization of the moth as a sloughing-off similar to the shedding of a skin.