Since the Middle Ages, that idea of a Land of Milk and Honey has been circulating in various cultures—a land without any need for labour, where a better and more prosperous life is possible. Ready-cooked food is there for the taking, wine flows straight out of the grapes, and even the buildings are tasty. A fountain of youth keeps bodies healthy, unwrinkled and pure. There is no property, wages are earned during sleep, laziness is rewarded and lies are honoured. Every day is a sunny Sunday.

This place, where people are free of worry and unfulfilled needs, was first detailed in ‘Le fabliau de Cocagne’ (France, ca. 1250), while the German language term ‘Schlaraffenland’ appeared in 1408. Whether it describes a utopia envisioned by the poor, who dream of a life without hunger and toil, or whether it represents a satirical, moralising view of the men of letters of the time: The perspective on that notion remains unknown. It is temporally situated either in the past—in an alleged Golden Age or Paradise—or in the future—as a hopeful vision for the afterlife.

In the present, the availability of food and particularly in affluent Western societies may provoke the thought whether industrialisation and globalisation have brought about these utopian conditions? 24/7 delivery services and meal kits, convenience food and preserves, overflowing supermarket shelves full of non-nutritional nutriments, fruit and vegetables regardless of region or season, takeaway food, all-you-can-eat restaurants etc. are permanent features of the everyday world of a growing number of people. The artworks in this exhibition are an encouragement to view these developments critically, and to reflect on the blessing or curse of urban prosperity, growing economic inequality on global and social levels, the relationship between excess, superfluity and scarcity, between nature and culture, and the value of labour and craft.

Held out towards the visitors by sharp metal claws protruding from the wall, the oversized asparagus ‘Untitled’ (2024) by Hannah Levy (*1991 in NY, lives and works in NY) oscillates in its limp, fragile and at the same time potent form between trophy and offering. As phallic analogies, vegetables such as cucumbers, pumpkins and asparagus take on an almost threatening presence in Levy’s artworks. The combination of cool metal and fleshy silicon, both eerily attractive and repellent, symbolises the now inseparable unity of the organic and the technical. In the exhibition, the work talks about the bodily relationship to food and the often invisible physical labour behind its production.

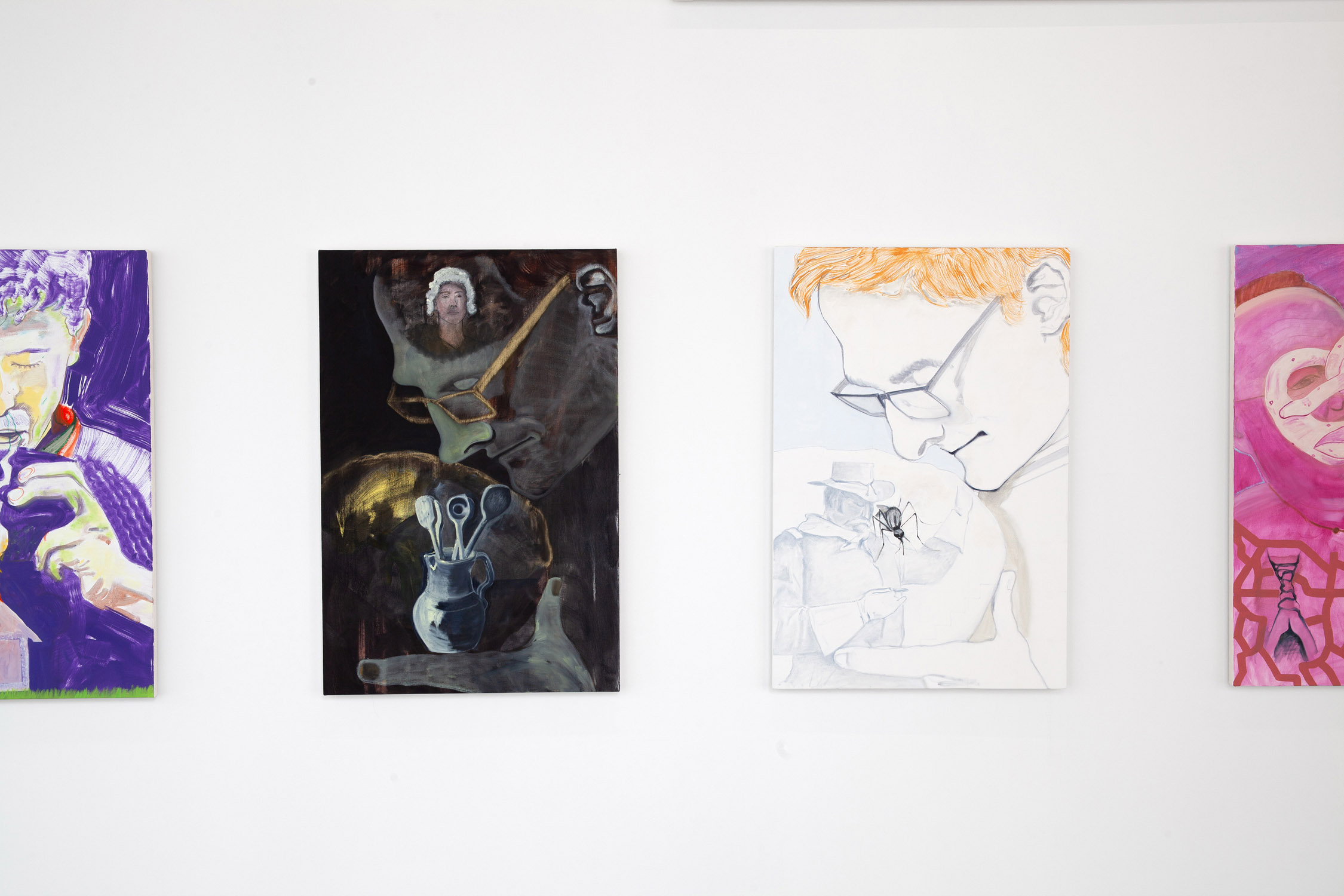

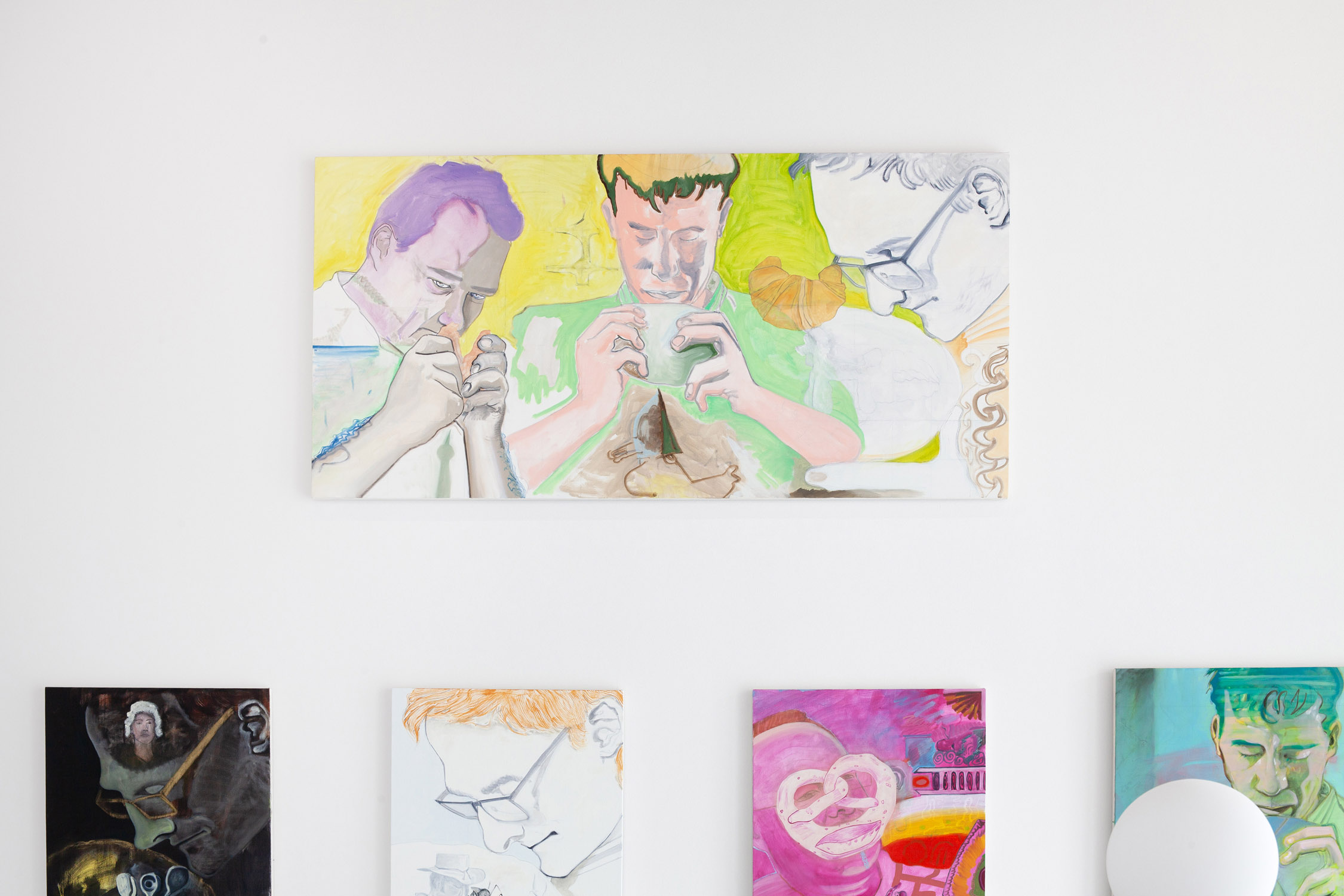

The series ‘Tag und Nacht im Leben einer Bäckerei’ (2022) by Vittorio Brodmann (*1987 Ettingen, CH, lives and works in Berlin and Zurich) is based on photographic portraits found online showing bread sommeliers undertaking quality control. Their hand gestures emphasise not the visual but the olfactory or tactile. Brodmann’s image worlds give the impression of memories evoked by the smell of bread, one of our oldest cultivated foods.

In his drawings, paintings fountain sculptures and installations of everyday objects Pablo Schlumberger (*1990 in Aachen, lives and works in Düsseldorf) deals with the moist and the humorous, with excess, deviation and inefficient productivity. A window in a canvas opens the view onto a bar-like bacchanalian arrangement of sculptures alluding to bar stools, side tables and serving trolleys that carry objects and drawings. Full-moon lamps also turn into drunken image carriers. Over many years, Schlumberger has built up a collection around the figure of the drinker as both a fun-loving and a tragic character—glasses, carafes, modified or quirky bottles, antiquarian figures and other items show how the form influences the act of drinking.

With her life size architectural interventions, Liza Dieckwisch (*1989 in Kiel, lives and works in Düsseldorf) transforms the exhibition space into a place of milk and honey, subtly and poetically playing with human longing for abundance, comfort and leisure. Instead of paintbrushes, Dieckwisch uses cooking utensils and takes inspiration from the materiality of food, its flowing and transformational qualities. Her work reflects on the ephemeral, on change and the process of its own creation.

Julia Gruner’s (*1984, lives and works in Köln) largescale print on a textile made of recycled plastic critically looks at waste of resources in the production of processed foods. Against a black background reminiscent of baroque still-life paintings, her print depicts an exuberant and overwhelming arrangement of scanned comestibles from those ‘Schlaraffenland’-narratives mentioned initially. Presented in its contemporary industrial form, the colorful variety of sweet and salty delights throws shade on the overly present food imagery in contemporary urban or digital advertisements.

Artist Mukbang (Gruner & Dieckwisch) aesthetically investigate the equally called internet phenomenon (mukbang being a Korean neologism derived from ‘meokneun’, to eat, and ‘bangsong’, to broadcast). Mukbang emerged in 2009 in South Korea as an attempt to escape loneliness by eating together online. But in time the focus shifted: the consumption of increasingly obscene amounts of food—often accompanied by ASMR (autonomous sensory meridian response)—turns the satisfaction of a basic need into a calculated system of producing likes and money, while food is scarce elsewhere.

This imbalance is also vital to the work of Belia Zanna Geetha Brückner (*1992 in Mönchengladbach, lives and works in Berlin), who examines the evolvement, transformation and manifestation of power structures through an analysis of forms of hospitality and menu creation. Her performance at the exhibition opening comprised exquisite canapés by a catering service normally exclusively contracted by private jet companies. Whenever a selected recipient turned down the offered food, the canapé was trashed for all to see. Her work ‘Kleine Ursache, große Wirkung.’ reflects on the upper 1% and their “apocalypse blindness” (Günther Anders) that loses sight of the future and sacrifices common sense to carpe diem.’ (Translated from Gerhard Oberlin, Schlaraffenland, Fluch und Segen des Wohlstands, 2022, p. 9.)

The inequality of use of resources is also addressed in the three works by Alwin Lay (*1984 in Lugoj, Romania, lives and works in Cologne). The artist reflects on desires, wishes and expectations projected onto everyday objects by meticulously choreographing them into experimental situations that take an unexpected turn. This includes the photograph ‘Knusprige Hähnchen’ (2018/2024), reminiscent of Wilhelm Busch, showing a disposable thermal bag overflowing with a thick, brown, chicken-teriyaki-like sauce. The video work ‘Strohhalm Rot Weiß’ (2014) shows an empty glass with a straw from which water seems to flow from nowhere. In his 24-part series ‘mod CLASSIC’ (2019), yet another liquid—coffee, the ‘lubricant of industrialisation’—flows continuously, filling up until the machine is ultimately submerged in it. The series becomes a parable of modern life, dominated by consumerism, efficiency, and ultimately, burnout.

Josephine Scheuer’s (*1993, Merzig, Saar, lives and works in Düsseldorf) ‘Handlauf’ ascends to the upper part of the exhibition with a sugary sweet aroma. The artist has covered the handrail of the spiral staircase with sugar paste (fondant), allowing visitors to leave their mark by touching it, similar to the fingerprint that individual actions leave behind in the world. Smooth and cold as marble, Scheuer’s material nestles around the institution’s architecture and humorously takes up the conventional use of sugar paste for decoration.

The multipart work ‘Not Moscow Not Mecca’ (2012), by the artist collective Slavs and Tatars uses different fruits as a linguistic, emotional or political ‘substitution’. The installation can be read as an autobiography of the flora of Central Asia, formerly called Eurasia. Its arrangements reflect the cultural richness and hybridity of this region: The mulberry tree crowning the installation is both food of the silkworm and symbol for the Silk Road, a historic trade route connecting China and the Middle East to Europe, enabling cultural and economic exchange; the quince in the shape of a globe is a linguistic substitution is called ’dunya’ in Serbo-Croat, while the Arabic ’dunya’ means ‘world’; the Hami melons made of blown glass play on the Slavic origin of ‘melon’ (the verb дыть = to blow), while the title ‘Fragrant Concubine’ derives from the legend of the beautiful, sweet-smelling Uigur Xian Fei; a wooden cucumber is bedded on a rahle, a frame for sacred writings; the textile depicts stitched pomegranates which are both fruit and grenade, alluding to the dual nature of destruction and fertility; the sour cherry descriptively derives from the Slavic verb ’vesit’ = to hang and ‘Holy Bukhara’, referring to a city where the Persian dialect and Hebrew script merge, highlights the syncretism that spans this body of work. Cross-cultural in their meanings, these fruits also stand for the ‘achievements’ of the globalised world: the continual availability of food regardless of region or season, and the associated loss of their cultural significance—but also for the ability to create new meanings.