Artists: Sarah & Charles

Exhibition title: W.O.R.M.

Venue: House of Chappaz, Valencia, Spain

Date: February 16 – May 17, 2024

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and House of Chappaz, Valencia

The Wormhole Burrow

“A great many, if not most, of these things have been described, inventoried, photographed, counted or enumerated. My aim in the pages that follow has been rather to describe the rest: what is not generally noted, what is not noticed, what is unimportant: what happens when nothing happens except weather, people, cars and clouds.”

Georges PEREC, An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris, 1975

“It is neither,” replied the voice of the sphere parsimoniously, “it is knowledge; it is the three dimensions: open your eyes again and try to look steadily.”

A. SQUARE, Flatland, 1884

The future stopped surprising us a long time ago, the great advances that were to come, the marvel of a wireless telephone or communicating by seeing someone on the other side of the world were assumed with astonishing normality. Some theorists have gone so far as to claim that the turn of the millennium meant the end of surprise, that in the nineties of the last century we could still experience astonishment…

It is almost two decades since Jameson published Archaeologies of the Future (2005) or since Documenta XII articulated its discourse around the idea of modernity as our antiquity (2007). The beginning of the century was built on the ruins, on fragments of utopias that no longer had a place in a time beyond us, but that showed themselves to us between our fingers, in front of our eyes… keys, screens, clicks.

“I repeat: I have imposed this obligation on myself not to leave out the slightest detail in my notes. That is why I must point out – even if it pains me – that even in our own state the process of hardening, of vital crystallisation, is not yet complete. We are still some way from the ideal. The ideal is to be found where nothing is happening any more”.

Yevgueni ZAMIATIN, We, 1922

We live in the information society, and there are many routes that have led us here. James R. Beniger in The Control Revolution. Technological and Economic Origins of the Information Society, he argues that the whole framework was created in the United States between 1830 and 1940: the arrival of the railway, the telegraph… There are numerous examples in Europe, along with many others that our Eurocentric vision has led us to ignore, but they all speak of a development in the volume of information generated by greater ease in the modes of communication.

In 2010 Eric Schmidt, CEO of Google, stated that in two days five exabytes of unique information were generated on the internet, that is to say, every two days the equivalent of all the information generated by humanity since the appearance of writing until 2003 was generated. If the capacity of our brain is forty Terabytes, it would take one million two hundred and fifty thousand minds to hold all the information that was generated in two days almost fifteen years ago. Currently that figure has grown exponentially.

“When time is considered, not as a succession of experiences, but as a collection of hours, minutes and seconds, the habits of increasing and saving time appear. Time takes on the character of a closed space: it can be divided, it can be filled, it can even be dilated by the invention of time-saving instruments”.

Lewis MUMFORD, Technics and Civilization, 1934.

This flow of information has generated a numbness, a situation of anaesthesia in which everything seems to be in the same place at the same time, a static continuum, a stream of images, data and emotions flowing in a single direction.

We acquire our knowledge through visual everyday frames, the flow of stimuli that shape our daily lives; The changes in this flow are what transform our imaginary and generate a change in the aesthetic paradigm, for example in 1910 the Futurist group in their manifesto resorts to a sculpture two millennia old to identify it with the past, while their admiration for the present is focused on the radiator of a car, any of these references not only form part of our past but we don’t even contemplate them as frames of aesthetic development, our temporality has been reduced so much that it has ended up expanding and becoming a place.

“In futurist theological jargon it means a man who believes that the prophecies of the Apocalypse will be fulfilled. These Italian artists knew next to nothing about theology, but they behaved as if they themselves were the horsemen.”.

Fritz Saxl, A Heritage of Images , 1957

Immersed in this scenario Sarah & Charles (Brussels, 1981 & 1979) have decided to position their practice in a search for strategies that involve assuming contradiction and enunciating it, generating a moment of suspension of meaning, propitiating collaborative processes, breaking with the isolation that the information society provokes and generating aesthetic devices that appeal not only to visual knowledge but also to haptic knowledge, employing not only visual production tools but also experiential and sensitive ones.

“The problem of information is an aesthetic problem (broadly understood—in terms of both affective senses and art) because we become informed through a variety of senses and forms. (…) Causal effect, however, is not the same as sensory, emotive, or cognitive affect. The functioning and production of “information” in social space, as well as the appearance of what we might call information in so-called mental states, is neither strictly causal nor easily described in operational terms.”

Ronald E. DAY, The modern invention of information : discourse, history, and power, 2001

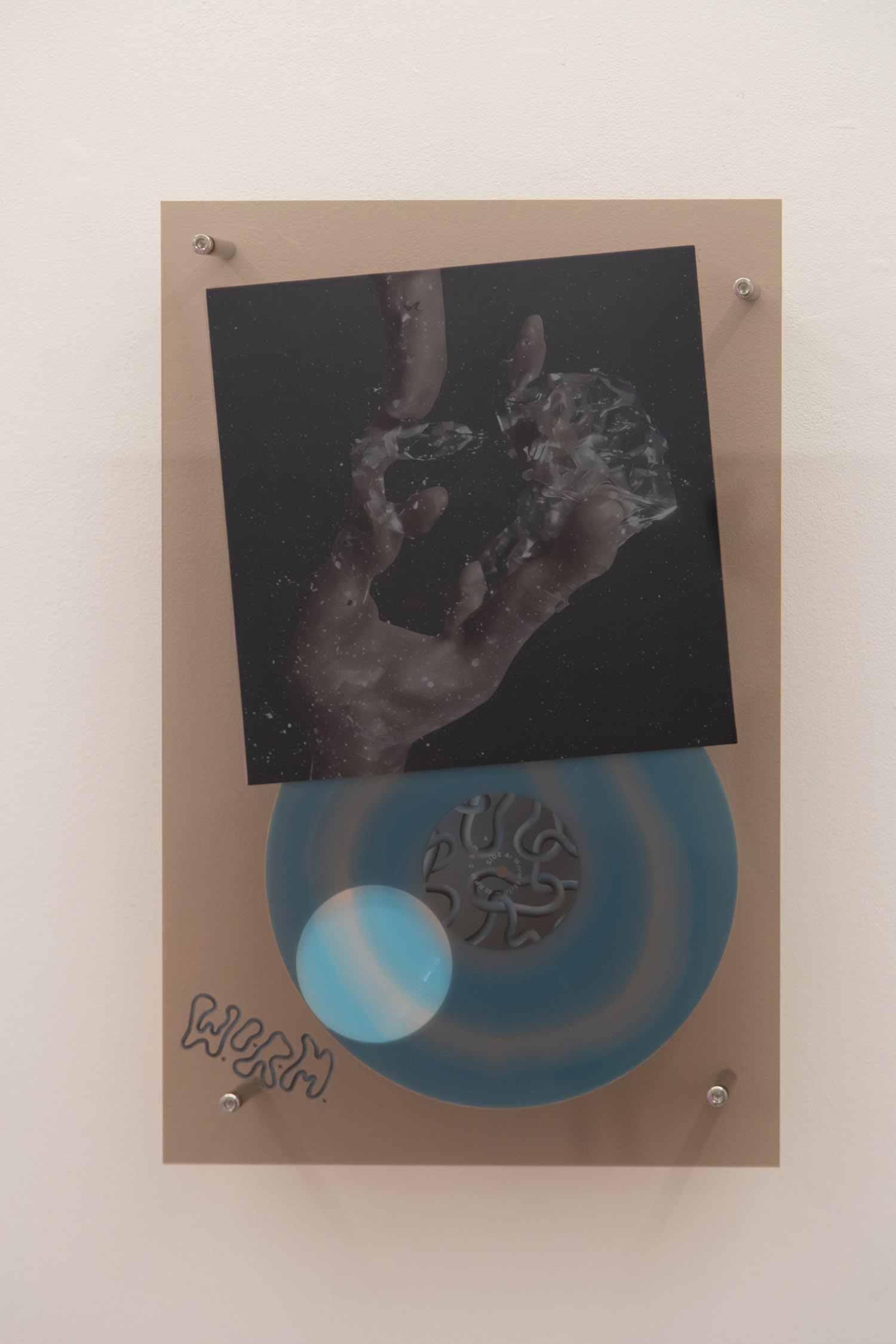

“W.O.R.M.”, an abbreviation of ‘Write once, read many’, which refers to mentioning everything that has been digitally reproduced, is the name under which they present their project in their first solo exhibition at House of Chappaz. Notions such as writing, information, knowledge and knowledge are contrasted with the modes of (in)communication and the loss of the message, not because of noise but because of the self-reproducibility of the message itself.

Using elements that appeal to a sense of “everyday security” such as furniture, cushions, vinyls… the artists introduce us into a space in which its supposed docility generates a feeling of gradual strangeness and unease.

“Le bonheur m’obsède à la névrose

Là où il y a du gris, je mets du rose”

Alain BERLINER, Rose, 1997

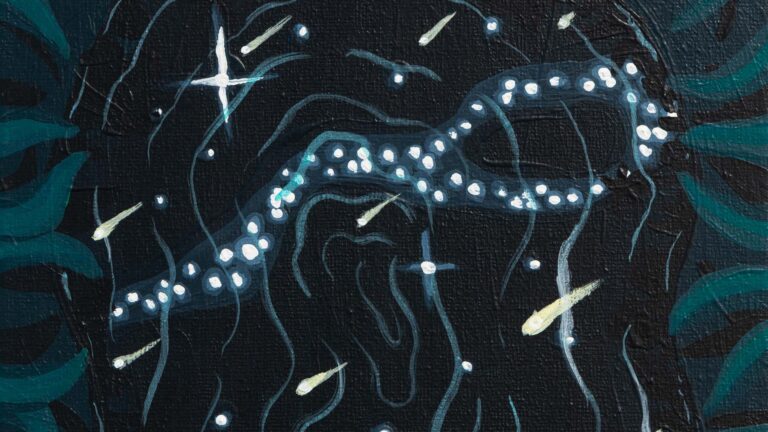

The title of the exhibition also plays with the multiplicity of meanings, with polysemy and therefore with the ‘non-fixation’ in a single meaning or ‘translation’, as it is a worm that is the protagonist of the video installation that generates the rest of the materials: Annelida (2024). Recovering sculptural forms already employed by Sarah & Charles, but presented in a much more ‘industrial’ way, we find a video in which a worm travels through a landscape plagued by images of mineral forms, just as in Flatland where the worlds are divided between two, three or more dimensions, the protagonist is confronted with these precious materials and their representation, confusing the importance or hierarchical structure of these precious objects.

It is interesting to note that since 1983 we have been talking about “data mining”, i.e. the automatic analysis of large amounts of data to detect patterns, anomalies and dependencies, a practice much criticised for proposing research devoid of an a priori thesis but which has become the driving force behind many IAs.

“Thrown violently on the first sand painting, the snake ends up destroying it to mix with the sand itself”.

Aby Warburg, The Ritual of the Snake, 1923

AI is the tool used to manipulate the voices until they become incomprehensible, but also the images of hands that try to grasp that information crystallised in precious stones while fingers, palms and wrists are deformed into a liquid flow unable to grasp those solid realities.

In 1910, while the Futurists fantasised about destroying all the documentary remains of the past, Paul Otlet and Henri La Fontaine created the Mundaneum. Both were closely identified with the ideas of Edmond Picard and more specifically with his 1889 text Essai de bibliographie de la paix, in which he proposed the possibility of achieving peace through the archiving of information. Following these ideas, Otlet not only set out to create an archive with all the knowledge available in the world, but he was forced to invent a system of organisation that would be the blueprint for modern documentary science. In his quest, he also contacted Le Corbusier to provide him with a new location while he investigated the technical possibilities of the time (photography, microfilming, etc.) in order to achieve his goal.

Sarah & Charles take a similar technical approach, exploring technique in order to propose discourses on knowledge and knowledges through an experience that is close to tactile. The other installation in the gallery plays on this friction and symbiosis of soft forms (the impression of the cushions) and hard forms (again glass) on which they place a collaborative device, a vinyl. Before talking about it, I’m interested in pointing out how knowledge is usually categorised as hard (natural) and soft (social) sciences, without stopping to think that from the social sciences and more specifically, from feminism, objectivity, neutrality and the concept of the natural have been widely questioned as categories linked to social constructs.

“(Duchamp) carried with him a card specifying his profession, “precision oculist”. After fifteen years in his new profession, he found himself in charge of a small village in the Porte de Versailles, where every year, for a month, the Invention Fair, known as the Concours Lépine, took place. The invention that Duchamp was trying to sell to the crowds that streamed through the crowded aisles of the hall was the phonograph disc. The discs came in packs of six, each with a spiral printed on each side, for a total of twelve different drawings.

Placed on the turntable platter, they spun silently while producing a series of effects or optical illusions.”

Rosalind KRAUSS, The optical unconscious, 1993

1925, Duchamp premiered Anemic Cinema, a seven-minute film in which spirals alternate with phrases written following this same structure, all these elements constantly rotating on the screen. Five years earlier he had created, together with Man Ray, the Rotating Glass Plates (Precision Optics), more than 20 years in which the spiral and the process that governs vision become the driving force of his research.

It’s also the spiral motif that we encounter in Sarah & Charles’s vinyl. Within it, we immerse ourselves in music composed by their longstanding collaborator, Lieven Dousselaere, who employed AI speech-to-speech models to reinterpret his own voice as well as all recorded instruments. Among these, texts by Leonardo da Vinci appear, nearly unintelligible due to the numerous times they’ve been read and reinterpreted by the AI (read many), despite being written only once (write once). At the same time we can find the tracks on Spotify, seeking to democratise the experience and continue exploring different ways of distributing artistic processes. At the same time, the cover of the album again includes the motif of the hands. The etymology of manipulate links us back to the hand, the extremity with which we govern while we are governed, like the puppets who are unaware that they are being manipulated.

In 1964 Julio Cortazar published one of his shortest stories, Continuidad de los parques, in which he describes the armchair, the comfortable environment in which the protagonist resumes reading a novel, we read with him, we know about the love plot that will be the motor of a crime of passion whose victim, we discover, is the reader himself sitting in his armchair, who reads the story of the novel that is being read by us, making us accomplices and victims of the crime.

W.O.R.M. also poses this volume of layers, in which we don’t know what role we play in this flow of data, in this finding of what we have been trying to find for so long, dazzled by so many marvellous works that no longer amaze us.

“Everything happens simultaneously and the distinctions that we will introduce here are only to facilitate our thinking. Always adjacent areas, or even those that are very distant, exert an influence on each other. This is why we should recognize the impetus, growing each day even greater in the organization of science, of the three great trends of our times: the power of associations, technological progress and the democratic orientation of institutions.”

Paul OTLET, Transformations in the Bibliographical Apparatus of the Sciences, 1918

Eduardo García Nieto

Independent curator and educator