The book launche of the publication Réfléchis bien and first issue in the Collection des prêts sur gage will take place on Sunday 15 June – 3pm at EAC (les halles) in Porrentruy. With texts by Deborah Müller and Boris Rebetez in French and German, 60 pages, 26 colour illustrations. Published by ∆ Edition

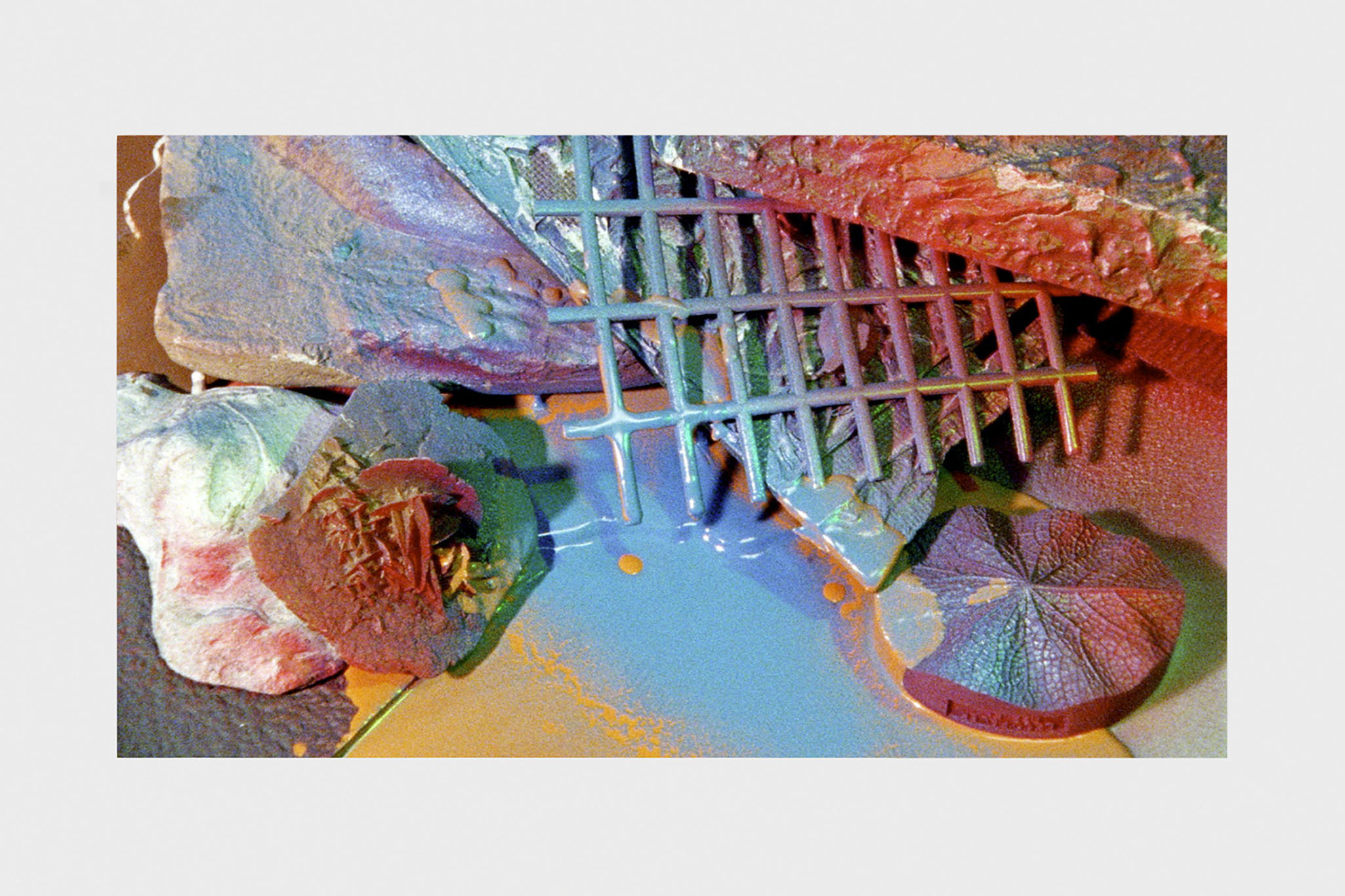

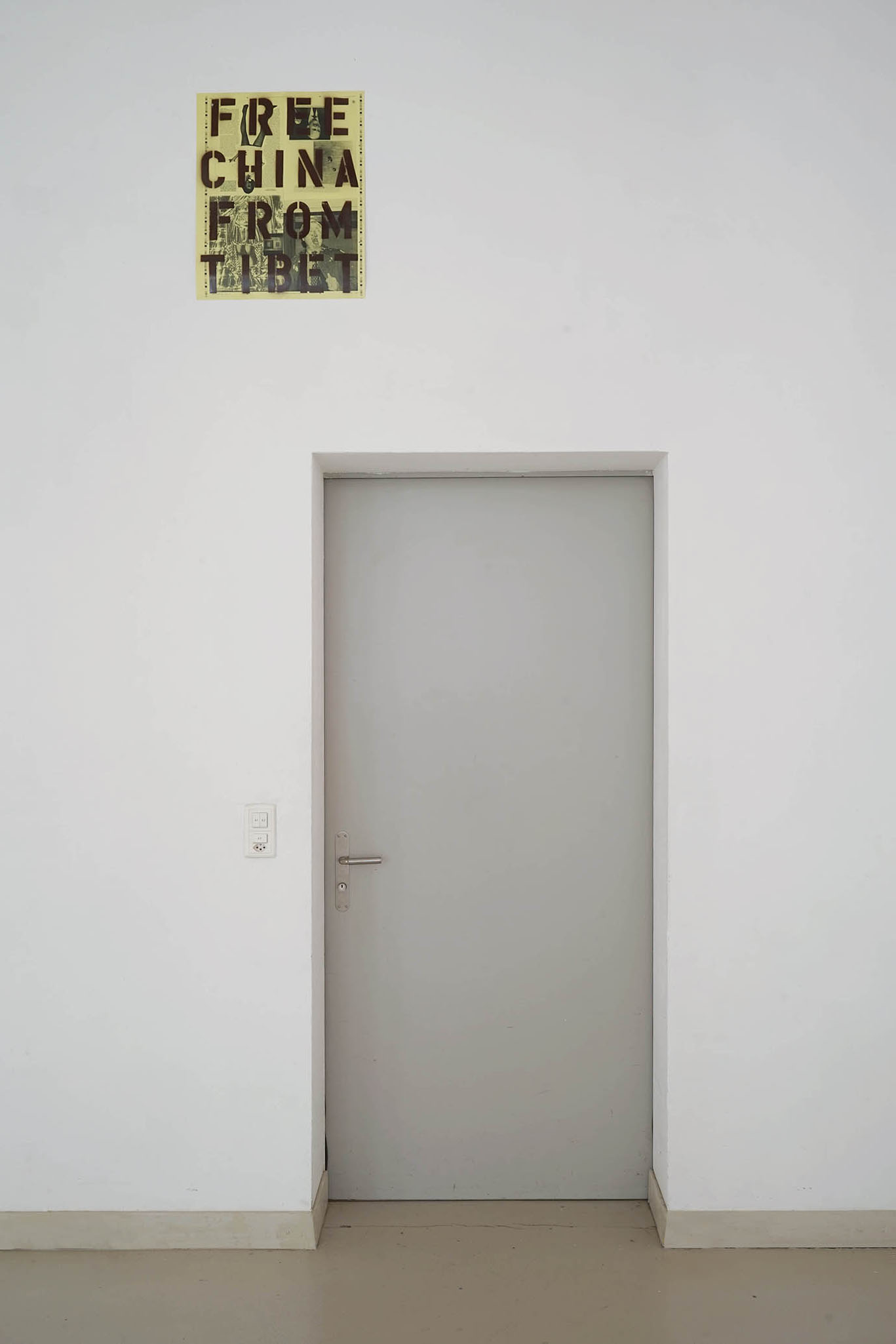

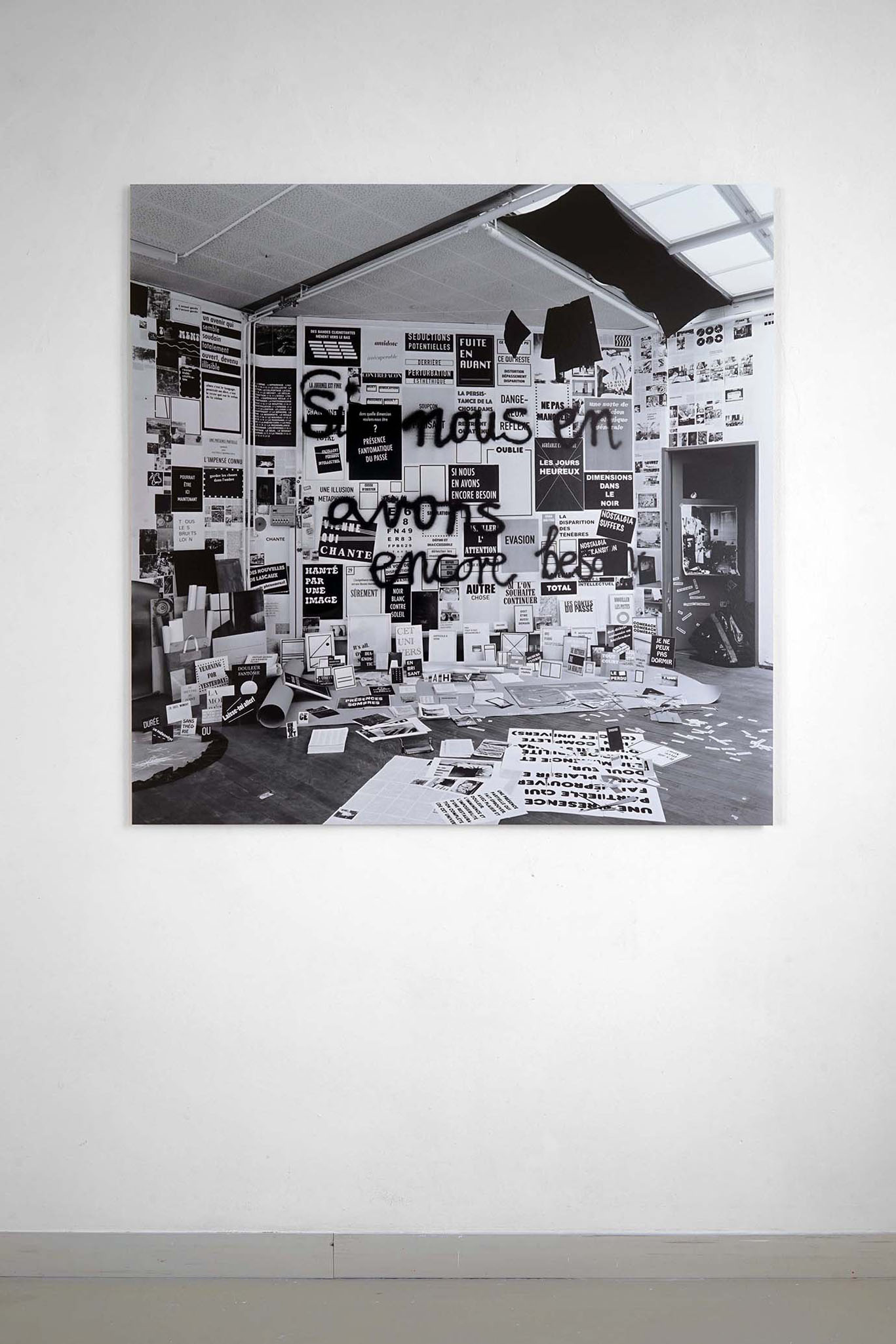

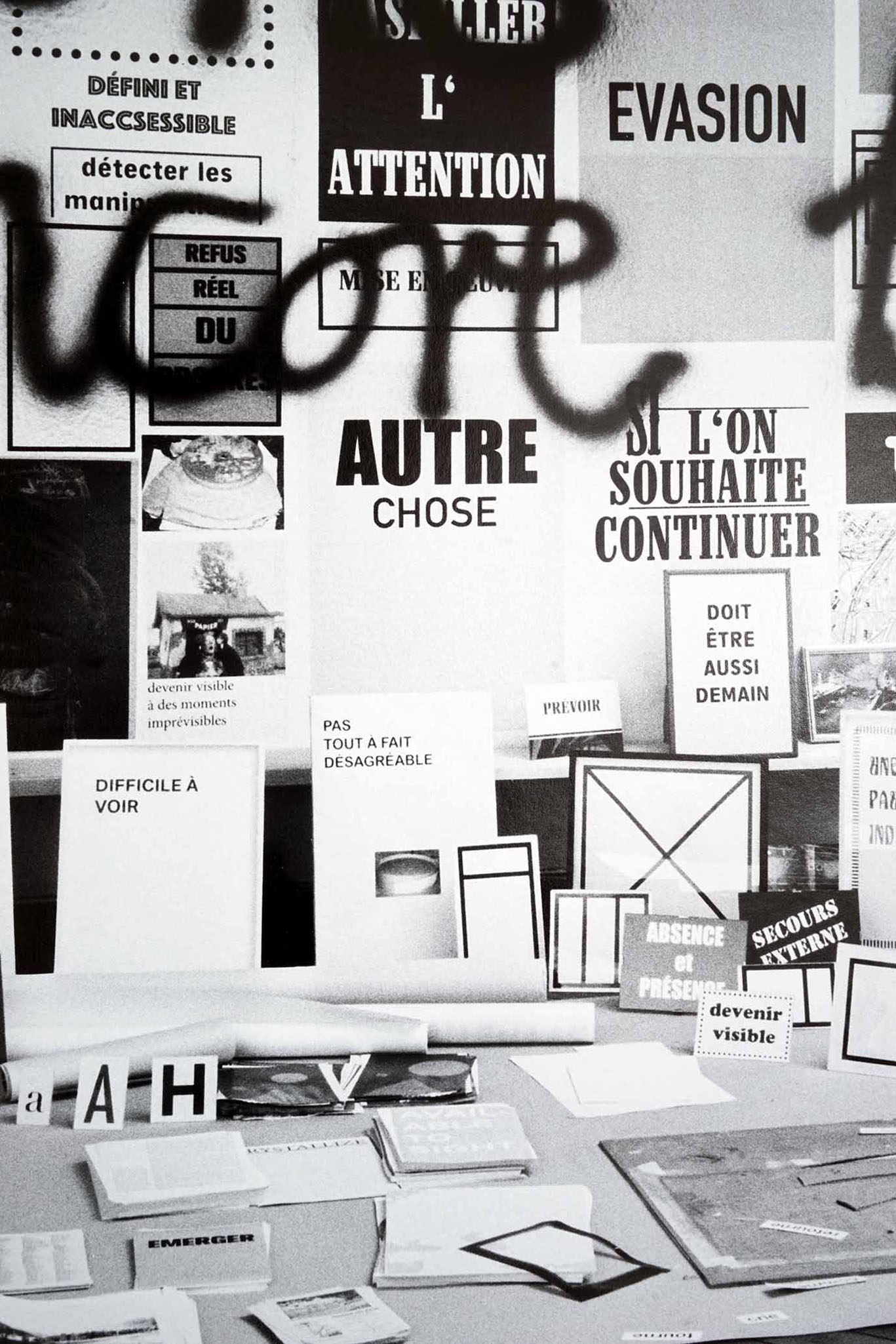

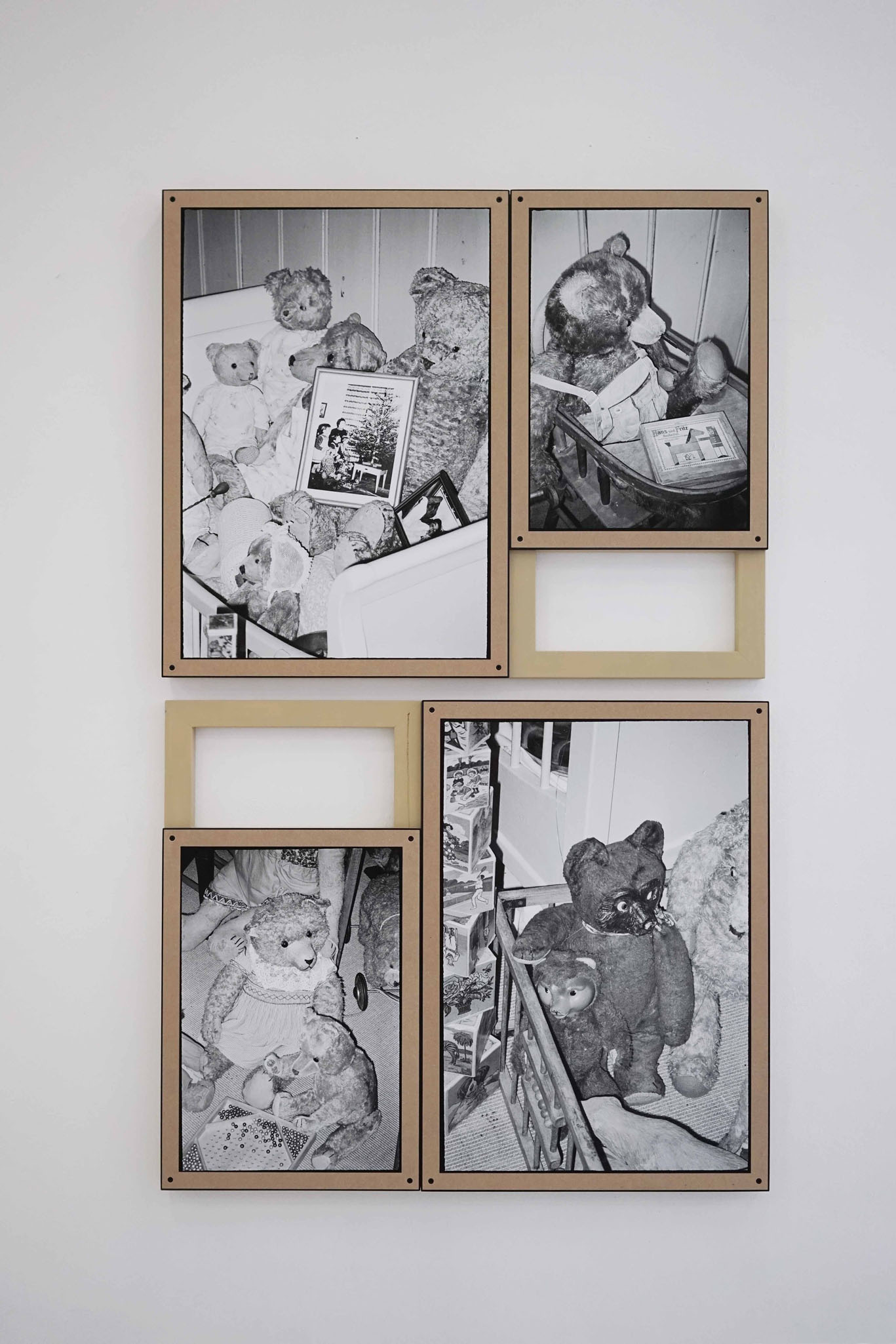

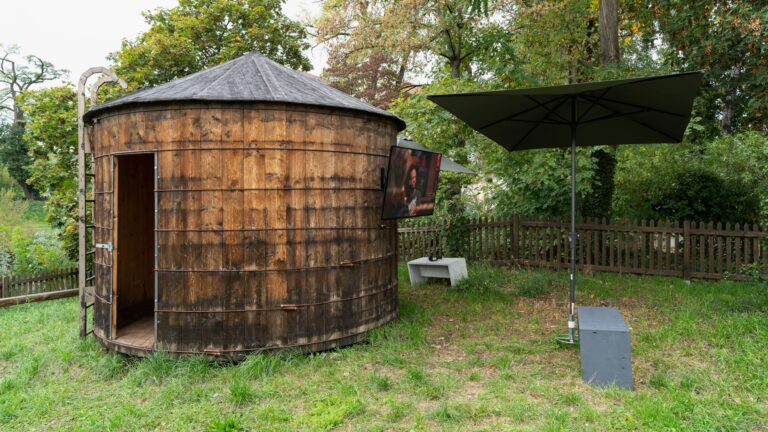

with: Sylvain Baumann – Isabelle Cornaro – Doris Lasch – Matthias Liechti – Rita McBride – Nico Müller – Willem Oorebeek – Bianca Pedrina – Kelly Tissot

“In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, all life presents as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation.”

— Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, 1967

Over the past two decades, technological advancements have transformed our modes of communication in radical and spectacular ways. The digital revolution means that anyone living in an area with Internet access and equipped with the right device can access a constant stream of information—and simultaneously contribute to it with their own data. According to French philosopher Michel Serres, this digital revolution, with its dizzying acceleration of communication and its profound impact on societal evolution, can be compared to the invention of the printing press 1 during the Renaissance—a technical innovation that resulted in the multiplication of access to knowledge and an early form of information democratization. Like every revolution, this one has brought progress and be-nefits, but also collateral damage, including the emergence of ideological debates that may have (or certainly did, according to Serres) led to the wars of religion. 2-3

The digital revolution, too, brings both benefits and unforeseen consequences. Much like the first printed books, which inserted them – selves between language and spoken word (oral memory), creating an external space (an external memory) 4 for the transmission of knowledge, the Internet also generates an external memory—but this time, virtual and volatile, capable of being shared and transfor-med by countless individuals. By inserting itself between individual or collective experience and its narration (its information), the Inter-net occupies a recorded space-time that is accessible and modifiable by virtually anyone. This results in the creation of a parallel world that reflects the “real world” continuously and almost in real time. But is this reflection true to reality? The answer is clearly no. Like any narrative produced through language or images, the Internet generates fictions that, at best, attempt to objectively convey reality and, at worst, seek to transform or distort it deliberately. This mirrored meta-world appears to be constantly under construction, like a stage on which users share or debate their experiences—reduced to digital data.

This representation of reality bears certain similarities to the science fiction novel The Invention of Morel, 5 written in 1940 by Argentine author Adolfo Bioy Casares. In the novel, set on a deserted island in the Pacific Ocean, the daily lives of a bourgeois society are filmed and recorded by a complex and sophisticated machine invented by Dr. Morel. The recorded images and sounds are then projected and played back in three dimensions in various places on the island. The people involved in the experiment ultimately meet a tragic end due to the recording and projection of their lives. Though the dark, apocalyptic vision in Casares’ novel is, of course, a metaphor, it can be interpreted—then and even more so now—as a metaphor for a physical existence giving way to a projected and virtual reality. However, the novel’s grim conclusion is not inevitable, nor is it the thesis or conclusion of this exhibition. To quote Michel Serres one last time: “Despite their tendency to cause destruction, revolutions remain forces for progress and evolution.”

The exhibition Refléchis bien seeks to explore this complex subject, bringing together a dozen works by artists from several genera – tions—some who experienced the digital revolution as adults, and others who grew up with it. The works selected for this exhibition each, in their own way, maintain a close or subtle connection with this theme. The acceleration of information transmission, the satu-ration of data, the replacement of the actor’s role by that of the spectator (or vice versa), and the distorted reflection of reality through new technologies all form an integral part of the exhibition’s content. These works all question our abilities—or our struggles—to live with these new channels and tools of communication.

–Boris Rebetez

3) “– Would you describe our era as a new Renaissance? Michel Serres: – Yes… and no. What is the Renaissance? It’s a time of multiple crises: religious, with the Reformation and the Wars of Religion; economic, with the birth of early capitalism; educational, with the rejection of scholasticism [the philosophy and theology taught in medieval universities] by the humanists; a crisis in our relationship with reality, with the mathematization of the world and the rise of experimental sciences; political, with a renewed idea of democracy. In short, it was a time of transformation like only three others in history: the invention of writing 5,000 years ago; the invention of the printing press in Europe in the mid-15th century; and today’s digital revolution. What’s extraordinary is that these three moments resemble each other in the nature of the crises they unleash, always in the same tectonic zones! Look at our time: like Montaigne’s France, we are facing a religious crisis, an education crisis, an economic crisis…”

— Michel Serres: The 21st Century, a New Renaissance? Interview by Sven Ortoli, published August 14, 2023, in Philosophie Magazine

4) A new radical shift in the support/message relationship occurred during the Renaissance with the invention of the printing press. The change did not affect either of the two elements directly, but rather the relationship between them. It marked a new form of externalization of human action into objects. Michel Serres observed that with the emergence of writing and the spread of printing, what we might call an “artificial memory” began to develop: mastering writing inevitably altered natural memo-ry, due to the transfer of information onto a material medium. With the spread of printing, people began to value a “well-formed mind” over a “well-filled mind,” relying on their “library” for knowledge storage. In a way, the invention of the printing press marked the birth of the first form of artificial memory—the book.

— Académie Française, Communication by Michel Serres, delivered during the session of Thursday, November 16, 2017 https://www.academie-francaise.fr/actualites/communication-de-m-michel-serres-0

5) The Invention of Morel (original title: La invención de Morel) is a novel by Argentine writer Adolfo Bioy Casares, first published in 1940. This classic of 20th-century fantastic literature tells the story of a narrator who seeks refuge on an island he believes to be deserted, only to discover it is inhabited by mysterious characters with whom no communication is possible. Strangely, the same scenes are repeated every week with absolute regularity.

— The Invention of Morel, translated from the Spanish by Armand Pierhal, Robert Laffont Editions, 1973