Artist: Ramon Hungerbühler

Exhibition title: Ratatouille

Curated by: Smallville

Venue: Smallville Espace d’art contemporain, Neuchâtel, Switzerland

Date: September 25 – October 24, 2020

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Smallville, Neuchâtel

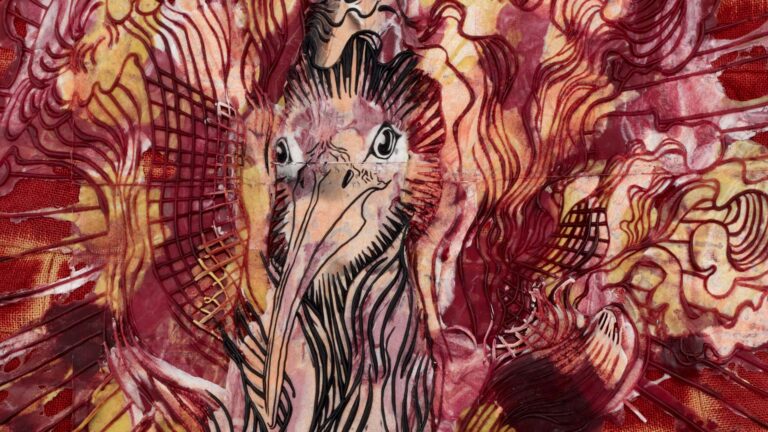

Deep under alienation a frog face would smile from the canvas. A little shy, but with kind, good-natured eyes. Affectively, the portrait is not reminiscent of his original Pepe the Frog, but of the Grinch. True to his bad-tempered nature, the prickly and bushy eyebrows stand suspiciously above the bloodshot eyes whose veins threaten to burst. Snot drips from the nose and a forked tongue protrudes from the smiling mouth. Here, even the lips, puffed up in the green face, no longer correspond to the original: instead of red, they are now poison green. The face is split into a green and a blue area, disturbed by the rectangles that appear to be in the colour scale.

Ramon Hungerbühler deliberately denies access to the well-known meme: Since 2005, the character Pepe the Frog by comic illustrator Matt Fury has had a virtual career in a wide variety of contexts and discourses. This got to the point where in 2016 Fury buried him in a drawn coffin after Pepe was appropriated as a symbol of the extreme right-wing Alt-Right movement. Since then Pepe has been considered a symbol of hate. Three years later, however, Pepe revived as the mascot of the pro-democracy freedom demonstrators in Hong Kong, despite his racist past in the US. The completely contrary uses of this figure reveal not only two mutually preventing/conflicting/contrasting/self-defeating attributions. They also herald an improbability to make generally valid statements at all today. It is precisely these iridescent positions and the fathoming of juxtapositions that are part of Ramon Hungerbühler’s artistic intentions. By pointing out the ambivalence, uncertainty and arbitrariness of content, Hungerbühler reveals the view of what lies behind. Whether, as in his early works, he formulates this by transferring the stroke produced in the Paint programme to the canvas, or whether he seeks out a poetry peculiar to painting in the portraits of shaky, shadowy figures in front of coloured canvases, or – as in the Offspace Mikro in Zurich 2018 – gets involved in a playing field of overlapping spaces that opens a dialogue on the relationship between reality and imagination; Hungerbühler’s compositions always invite us to negotiate painting as such.

The most recent works in the exhibition Ratatouille also move within this field of tension. The title may be misleading at first, as it alludes to a complexity that suggests levels, layers and overlaps. In the exploration of the conditions of painting, this time Hungerbühler does not however pursue the depths but the infinite vastness as the basis of paintings existence. The some 20 paintings are now modular, nonfigurative and figurative at the same time and have a broad reference list. In this, the depictions provoke an examination of the conditions under which everyday objects, including digital objects such as Pepe the Frog, produce meaning. Here Pepe is also a possibility of this frog figure. Although unrecognisable in his spitefulness, he holds a garlic in his hand, as if he knew about his hypertrophic fate and as if he wanted to ward off a looming disaster. And yet flies swarm around the bulb as well as the garlic being on fire. No way of doing anything with it anymore. If Ramon Hungerbühler, on the basis of the ill-tempered Pepe doppelganger with a snotty nose, is involved on the surface of pop-cultural discourse, then a quite simple art-historical formula could be used to explain the counter-reflex to his abstract art: If artistic practice has explored and documented something in its being as Hungerbühler explored and documented the simple stroke, then from now on it can represent everything without getting entangled in the problems of interpretative power and authenticity. By transferring symbols from the virtual space to the canvas, Hungerbühler makes memes like Pepe the Frog manifest and unique, but he removes an unambiguity in the disclosure of their wear and tear, in their re-presentation through alienation. In this sense Hungerbühler reduces, reinterprets and represents the symbols and gives them over to a homogenising flatness through his painting. Here the motifs used are in abundance: a piece of Emmental cheese, skittles in goulash soup, a knife as if carried by the scream killer, comic-like wooden boards, an abstract pear.

Being Swiss and painting a piece of cheese is hardly original. Even if this piece wants to be wholesome and down to earth. That is why it is important to look closely. The gesture with which Hungerbühler paints the cheese reveals, in the complete withdrawal of the style, in the patient levelling of the colour sections, not only a disturbance of traditional painting in the mode of a graphic print, but also exposes the Emmental painted so smoothly in its own clichéd form. The fact that it does not quite fit into the picture format also leads us on a trail, at the end of which complete insignificance threatens and the painting no longer seems to have any feeling for the subject. The same applies to the knife, which just about fits into the picture space, dividing it into two colour fields. In addition, there are the repetitive geometric structures, whose framework in one painting changes into a gender-fluid figure, but in the other, on the same basic composition, into three short black strokes, one of which begins to detach itself from the geometric grid, as if it had been tired of the concrete ground. As a mere allusion the paintings would now easily be converted as/to postmodern archival work and reappraisal of the past art historical century. In that Hungerbühler underpins his paintings with the concept of the Readymades, however, the symbols enter into a paradox that hardly specifies the imaginary space that Hungerbühler seeks to line, but rather allows it to gradually fade away. Due to its industrial seriality, the Readymade can be multiplied at will: the more that is added, the more its importance fades as it grows. Hungerbühler’s concept of a Readymade hardly corresponds solely to the artistic strategy of transferring an everyday object into the art context, which also includes the consciously chosen formats, as they correspond to the masses of a smartphone, the super widescreen or the squares of Instagram. Rather, the painting can be traced back to Marcel Duchamp, the forefather of the Readymades, and his statement that every painting since industrialisation is a Readymade: “Because the tubes of paint used by the artist are industrial readymade products, we have to conclude that all paintings around the world are ‘helped readymades’ and also assemblage works.”

Made of synthetic acrylic of the Bau und Hobby brand Amsterdam, Hungerbühler’s works correspond to a Duchamp’s Readymade by their materiality alone – the subjects are helped or assembled. And it is precisely here that an exciting approach is indicated: According to the industrial nature of the Readymades, it can always be updated, reborn, so to speak. If, according to Duchamp, all the paintings ever painted with industrial paint and all the paintings ever to be realised are already inscribed in the contingent of these industrial colours, then the subject becomes obsolete. There could also be 20 Emmentaler cheeses on display. The symbol has become absolutely secondary. Or rather: The symbol threatens to have become absolutely secondary. The relationship between what is represented and its meaning is disturbed by the factors of repeatability and industrial colour. In this sense, the pictures do not build on each other, but merge into each other, which is almost symbolically represented by the painting of the four-part folding picture. Surrealistically, the artist Hungerbühler challenges the tradition with a painting game that some people will know from children’s birthdays, but others know it as Cadavre Exquis or Exquisite Corpse. For those who are unfamiliar with it, the game goes as follows – here intended for four painters: first the head is sketched on the first quarter of the sheet, the sheet is folded and passed on. The next person now applies the crayon where the neck of the already painted head ends, without knowing what appearance it has received. This is followed, again unaware of what was drawn before, by the legs, and finally the feet. In the gesture of playing with himself, Hungerbühler is hereby challenging his own spectrum of forms. He wants to surprise himself and outsiders, fathom out in the play of forms and make suitable what at first glance does not belong together and yet can stand next to each other. Because that is exactly what painting can do. This can be seen in the detail of the head of this flat figure: as a kind of box whose head is shaped in such a way that playful shapes form a headdress, this silly, smiling figure holds a star to his forehead.

However, there is no equivalent for this form, which is probably due to the fact that the arm whose hand holds the star winds upwards from the second quarter of the folding picture and, according to the logic of the game, could not have known that there was a headdress of shaped holes.

Behind these humorous details and mise-en-abyme of forms hide the most precise calculations: The folding picture is no accidental gimmick, but on the one hand a deliberate use of the infantile language of form and on the other hand a witness to the modularly merging of the painting. The star would fit much better to the three stars on black background of the other painting. Ratatouille unfolds as a frame of reference braised from sedimentary layers of colour and stages in the history of art, offering an infinite variety of shapes and colours, without Hungerbühler making hasty and appropriating use of them. It is true that Hungerbühler moves on a narrow ridge, as everything seems somehow familiar and yet cannot be clearly classified. It is this suggested proximity that is intended. It allows the artist to place the viewer on the Achilles’ heel of the familiar. The objects depicted here, however, no longer have a common language; they come from the flatness of the infinitely born and the readymades of industrial acrylic paint that are to follow. These mere markings in the countless possible versions are reflected in the titles of the works: X. X is two crossing strokes, it is a number and a letter, it can be a kiss, an adventurous reference on a treasure map and in this sense it is a trace above all else.Whatever one might have taken for the solid ground of the paintings; it frays, runs and at some point dissolves completely into loops and ribbons, demonstrating its own artificiality in the colour fields: violet and aquamarine, orange, white and brown. Without the tip, the pear would be lost. 3

[1] see e.g. http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/pepe-the-frog .

[2] Marcel Duchamp, Hinsichtlich der Readymades 1961, in: The Writings, translated, annotated and edited by Serge Stauffer, Zurich 1994, p. 242.

[3] Studio Looser about Ratatouille, Ramon Hungerbühler, 25.9.2020, Smallville in Neuchâtel