A rectangular structure is laid out on the floor of the Kunsthalle Arbon. Its shape is reminiscent of an archaeological excavation site, a labyrinth or the floor plan of a house. The title of the exhibition adds further associations: a dormitório is a bedroom or a dormitory. In ancient times, cemeteries were also referred to as such: the ancient Greek word “koimeterion”, from which the word cemetery is derived in many languages, basically simply means a place to sleep. The cemetery, the sleeping place, the house, the ruin: for Paulo Wirz (*1990 in Pindamonhangaba), the connection between these different places is of personal significance. In Brazil, he grew up in a house next to a cemetery and a wasteland. Emptiness, death, but also Afro-Brazilian religions shaped his interest in how people develop rituals and customs to deal with the big issues of life. What myths and narratives do we develop to deal with the unanswered questions of life, to find meaning and comfort? What kind of objects are created in the context of this practice? These are the kinds of questions that Paulo Wirz – like an anthropologist – investigates with his installations.

In The Sacred and the Profane (1990), the Romanian religious scholar Mircea Eliade writes about how everyday objects become cultic objects through ritual acts. The sacred, according to his central point, does not lie in the object itself, but in our handling of it – something that Wirz has also repeatedly observed in the religious practices of Brazilian Candomblé: jewelry, glasses, shells and other everyday objects are transformed into symbolic objects. Incidentally, works of art are also such cultically charged objects, which are given their value through a sophisticated system of value assignment – from medieval icons to modern masterpieces. Another important reference for Wirz is the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard. In Poetics of Space (1958), he writes about what constitutes a house. For him, it is not the physical building that is decisive, but the entirety of memory, history and imagination associated with the place.

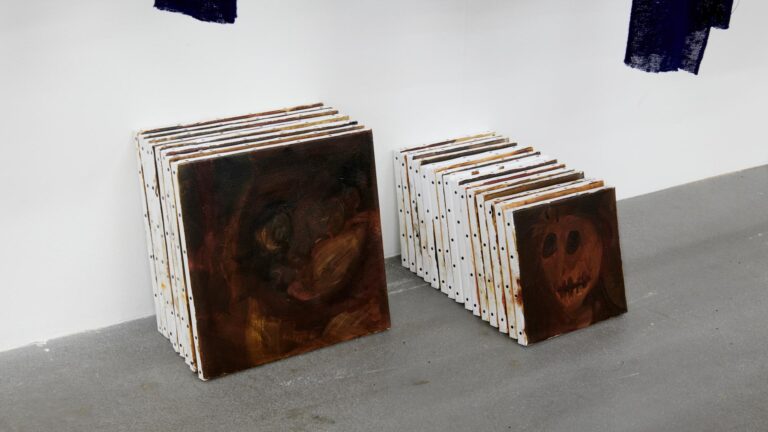

Paulo Wirz’s installation suggests a division into different rooms or spaces. It is not a reference to a building that exists somewhere. Rather, the division of the space is based on references to various places where the artist has lived. The objects that make up the structure also have a history. Wirz has already used many of them in earlier installations. They all address the themes of transience and preservation in different ways and work with the ambivalence of presence, absence, materiality and immateriality. They thematize fleetingness and permanence, integrity and fragility, but also decay and preservation.

A thin red thread is wrapped around all objects. In Greek mythology, Ariadne’s thread served as a means of finding her way out of the labyrinth. The installation is entitled Encruzilhada, which means a crossroads or a critical point at which a decision has to be made. In Wirz’s installation, the thread is no help in this respect. It does not show us a way out, but rather creates connections between the individual objects. Instead of releasing us from the complexity, it draws us further into the entanglements between the sacred and the profane, between ritual and everyday action. In doing so, he traces a story that tells of how people deal with the challenges of life and the uncertainty of their world. A question that has personal relevance, but also political urgency in view of current global crises such as war, climate change and security of supply.

The artist would like to thank the following people for their support: Andrea Nastac, Bogdan Balan, Bogdan Olaru, Cristina Vasilescu, David Knuckey, Felipe Schwager Hans Abegglen , Inge Abegglen, Inês Lima, Ling Huang, Lourenço Soares, Lucas Wirz, M. Victoria Abujamra Wirz, Marcel Schock, Marco Antonini, Maria Lungu, Mario Wimmer, Martin Jaeggi, Martina Venanzoni, Matheline Marmy, Pedro Wirz, Raphael Gygax, Ricardo Wirz, Ștefan Tănase, Valentina Triet, Vicente Lesser.