Artists: Marissa Bluestone, Terry Evans, Emma Hedditch, Xylor Jane, Baseera Khan, Sable Elyse Smith

Exhibition title: Other Romances

Curated by: Em Rooney

Venue: Rachel Uffner Gallery, New York, US

Date: September 10 – October 29, 2017

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Rachel Uffner Gallery, New York

Their words passed

through. With a

Blue-Greeness the

Thick of the Glass

The Fluorescent Light

It Buzzes and Can’t be

Drowned Out, If you

Think it’s Ceased it’s

Because the Buzz has

Now Become a Part

of You. You walk Around

With it. I Walk Around

With it. Becoming.

Sable and I emailed over the winter about a piece of hers, an aluminum sign board, with the above words, in plastic letters, on felt, behind glass, inside it. Another sign board piece, from the same show, was about her father, and had two keys on the side—one in the lock and one hanging off. I wrote her: Ursula K Le Guin uses the key and lock metaphor at the end of one of her novellas: self-love is the key and the lock is desire for another and the door is love— it won’t open without the key. Sable wrote to me about an excerpt from Audre Lorde’s Uses of the Erotic. To paraphrase; eroticism courses through us all the time, determining our ethos, our empathy, and our presentness.

Housing projects in Chicago built on lead reservoirs from bygone factories get demolished, neighboring bodies breathe in the dust. Satellite images of sprawling prisons, resembling mass graves, quiet those calmed by the containment of the people inside. A red cross on the top of a hospital gets seen, ignored, targeted and bombed.

Cul-de-sacers, worshipers, prisoners, detainees, workers, shoppers, and patients alike—the containers that hold us, form us too.

Last week, the president of the United States of America encouraged a small and grotesque act: roughly cramming suspects into police cars. Behind him rows of officers swam uncomfortably in their polyester uniforms.

Catherine Opie, gets out of her car early in the morning and photographs the freeways outside of LA.

The roads in Opie’s series Freeways are empty and looming like science fiction playgrounds. Because I grew up in the country they seem, to me, stark, alien, and beautiful—like the desert. Marissa, though, having grown up in Teaneck, New Jersey a close suburb of New York City, knew the architecture of the overpass. For her they always symbolized her romantic departures from home, towards the city.

I think the photographs are meant to be about archeology in some way (today’s freeways are yesterday’s pyramids), but I can’t not think about Catherine Opie, as portrayed in her famous 1993 Self Portrait/Cutting, with a bleeding pictogram on her back of two female stick figures, a house, and the sky, getting out of her car and standing to the side of the road somewhere, with her camera to her face. To make a picture with your body is to be made vulnerable—looking, stealing, cars and people racing by, or alone with one other person, or with yourself.

Sometimes I like to imagine a piece of fabric, hung between two trees, strong enough to hold my entire core comfortably —not a thong and not a hammock but somewhere in between. I want to hang here, gravity pulling my hips towards the ground in opposite directions, with my arms loose, and my eyes closed, seeing the red sky through my lids.

Architectures, and their byproducts, get into us, with their awe, with their traumas of alienation, and never go away. We build our own houses of worship, sew our own clothes, and accept the codes that have been put upon us neither better, nor worse, but always.

As our mortal bonds are subjugated to continual suppression at the hands of infrastructure (some as benign as waiting rooms, or subway cars—some as maleficent as pipelines, or holding cells), and as these structures etch through our landscape and hover over our heads we float, not quite poets but between poetry and the sun—in the realm of the visual. We see/feel/imagine industrial forces and respond to them with our bodies, through the production of images, through the production of ourselves.

Em Rooney

Curator, Other Romances

Other Romances, 2017, exhibition view, Rachel Uffner Gallery, New York

Other Romances, 2017, exhibition view, Rachel Uffner Gallery, New York

Other Romances, 2017, exhibition view, Rachel Uffner Gallery, New York

Other Romances, 2017, exhibition view, Rachel Uffner Gallery, New York

Other Romances, 2017, exhibition view, Rachel Uffner Gallery, New York

Other Romances, 2017, exhibition view, Rachel Uffner Gallery, New York

Other Romances, 2017, exhibition view, Rachel Uffner Gallery, New York

Other Romances, 2017, exhibition view, Rachel Uffner Gallery, New York

Terry Evans, Smoky Hill Weapon Range Target 2, February 1, 1991, gelatin silver print, Unframed: 15 x 15 inches, (38.1 x 38.1 cm)

Marissa Bluestone, Dance Party, 2017, oil on canvas, 63 x 48 inches, (160 x 121.9 cm)

Sable Elyse Smith, As if bending — like a mute scream, 2017, acrylic, steel cot, metal folding chair, 64 x 30 x 18 inches, (162.6 x 76.2 x 45.7 cm)

Baseera Khan, Position 3, 2017, c-print, 28 1/4 x 28 1/4 inches, (71.8 x 71.8 cm)

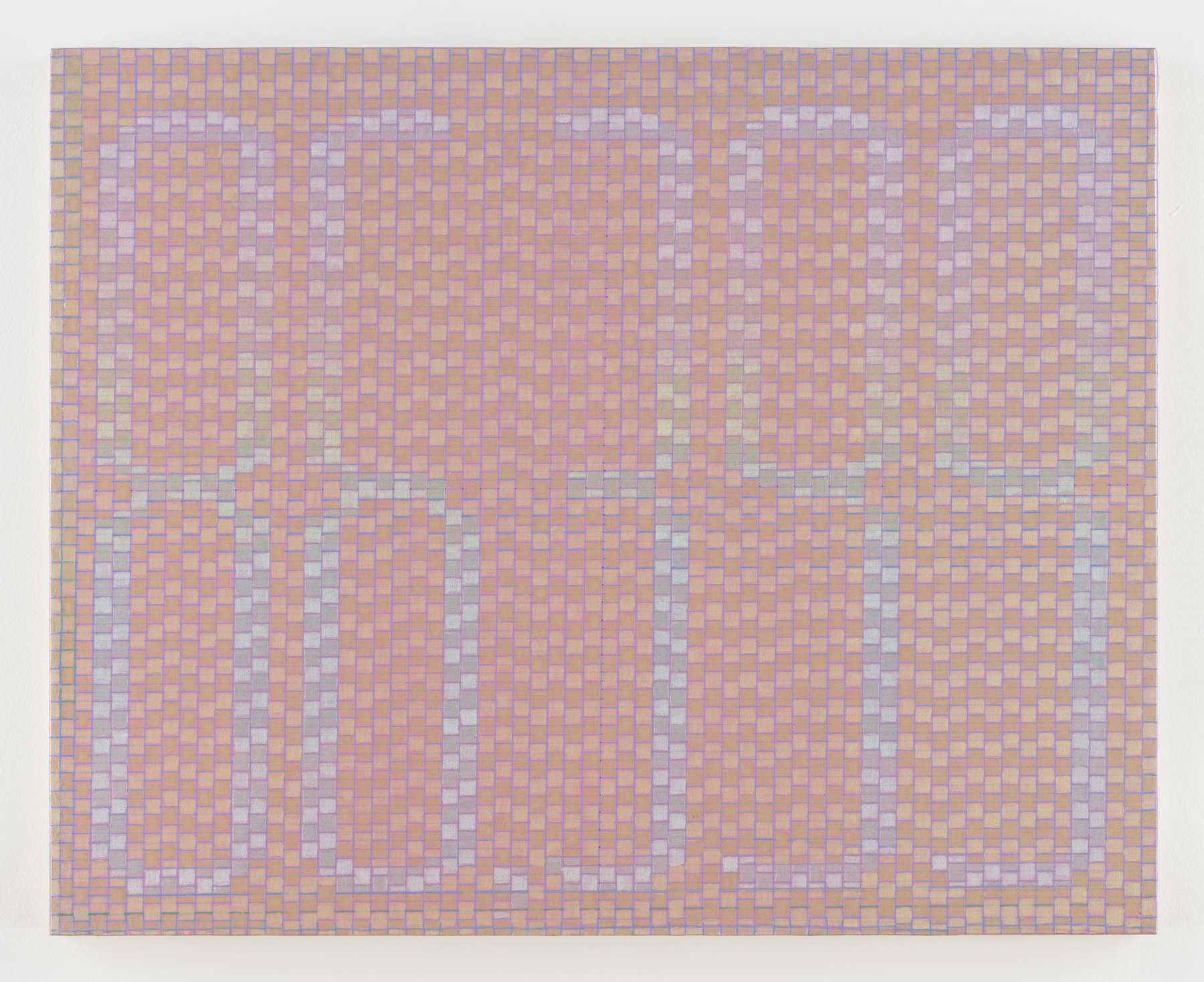

Xylor Jane, Leap Second III, 2017, ink and oil on panel, 16 x 20 inches, (40.6 x 50.8 cm)

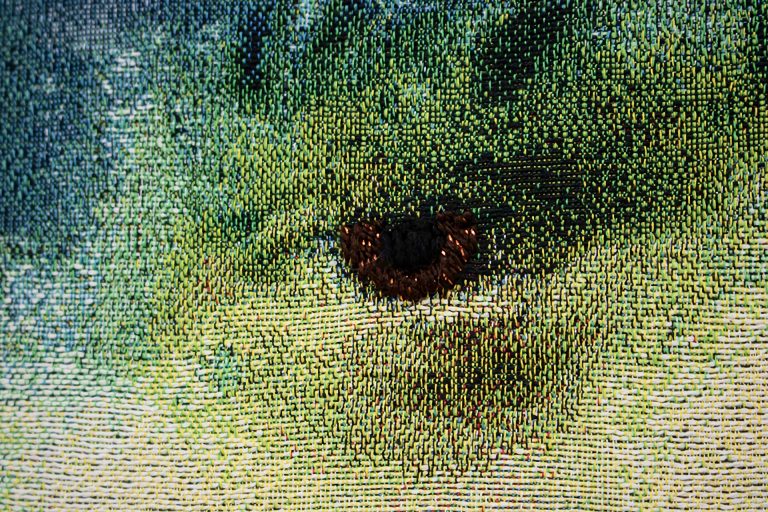

Marissa Bluestone, Traversing the Gap, 2017, oil on canvas,77 x 56 inches, (195.6 x 142.2 cm)

Emma Hedditch, Claim A Hand, 2017, cut-up used socks arranged on cardboard, 3/4 x 42 x 30 inches, (1.9 x 106.7 x 76.2 cm)

Emma Hedditch, Off Label, 2017, used plaid button-down shirt taken apart and sewn back together on cardboard display, 22 x 20 x 12 inches, (55.9 x 50.8 x 30.5 cm)

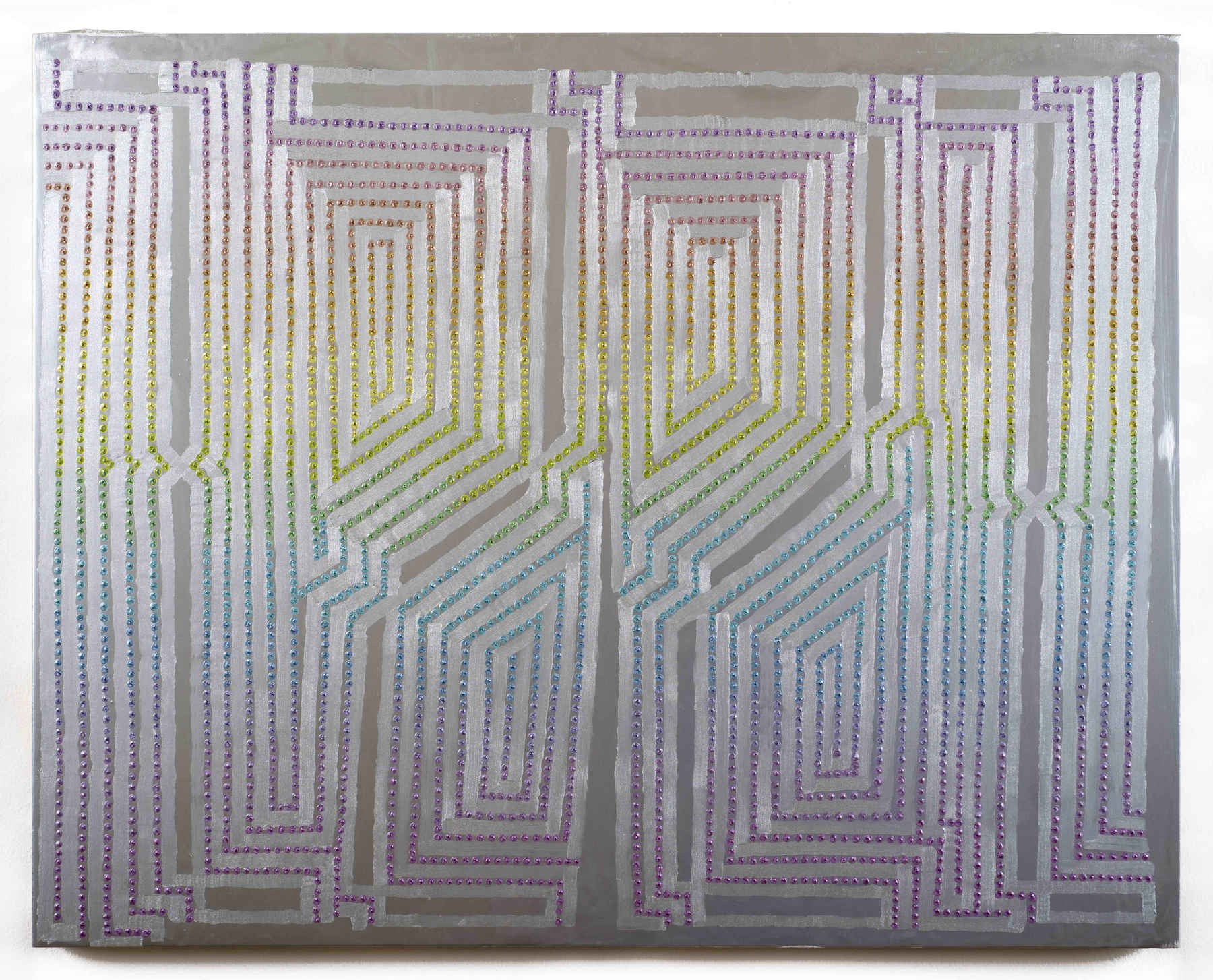

Xylor Jane, 12/21, 2016, oil on panel, 16 x 20 inches, (40.6 x 50.8 cm)