Green, how I want you green.

Green wind. Green branches.

The ship out on the sea

and the horse on the mountain.

–Federico García Lorca

This series of films departs from a conversation on landscape in the poetry of Federico Garcia Lorca and Mahmoud Darwish. It posits landscape as a place of connection as well as a reflection on memory, distance, and exile. The figure of the olive tree connects a wide Mediterranean region through millennia of parallel agricultural ritual and ecological coexistence. The olive branch is known as a symbol of peace while residing in a region that has been cut apart and divided.

Trees are a living archive of the land. Olive trees can live up to thousands of years, making them a stable and familiar element for generations of their neighbours. The olive branch is a symbol of peace whose stable grip has been wrested from the soil. They are also targets in the ongoing catastrophe in Palestine that is impossible not to speak of.

***

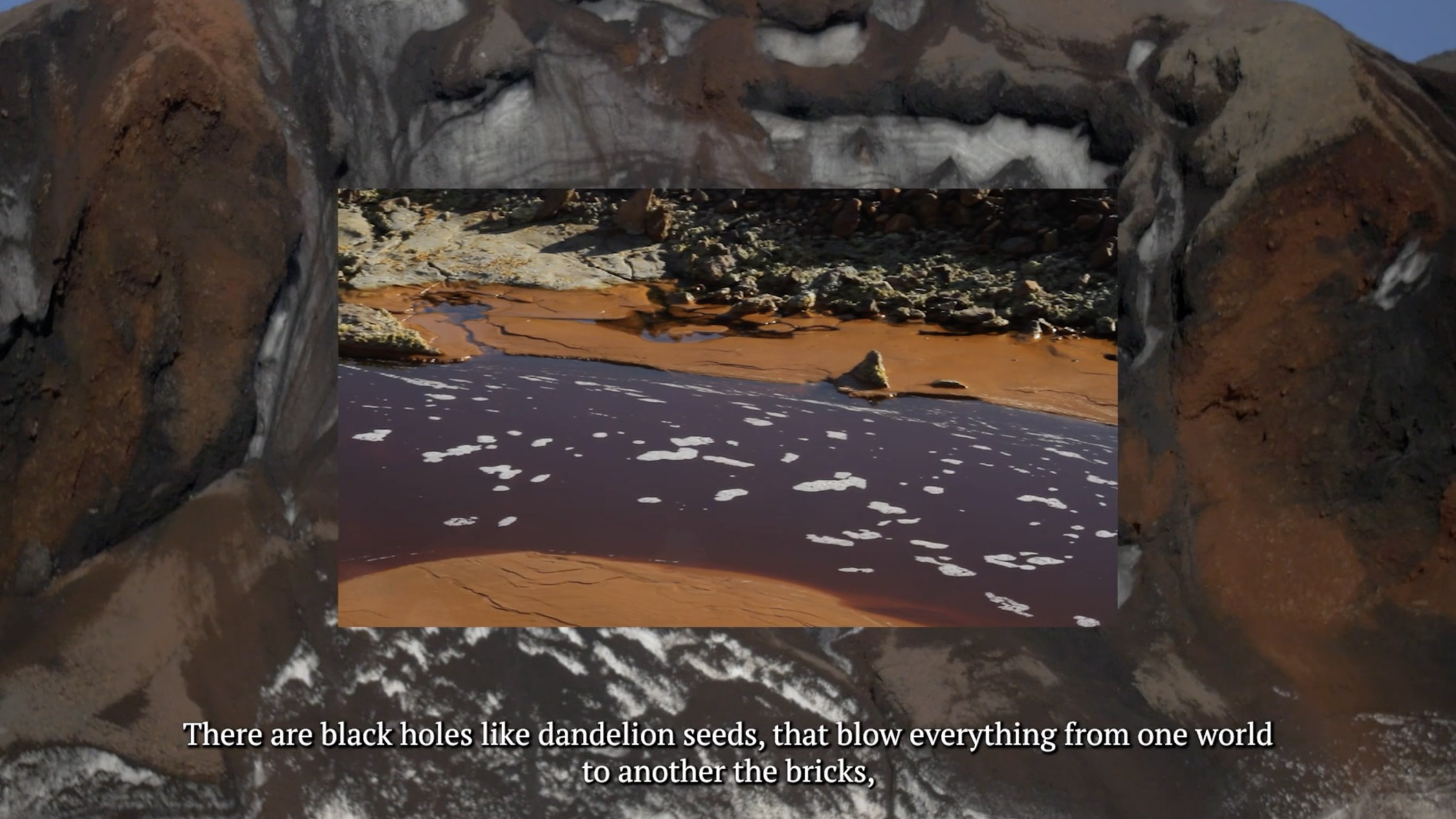

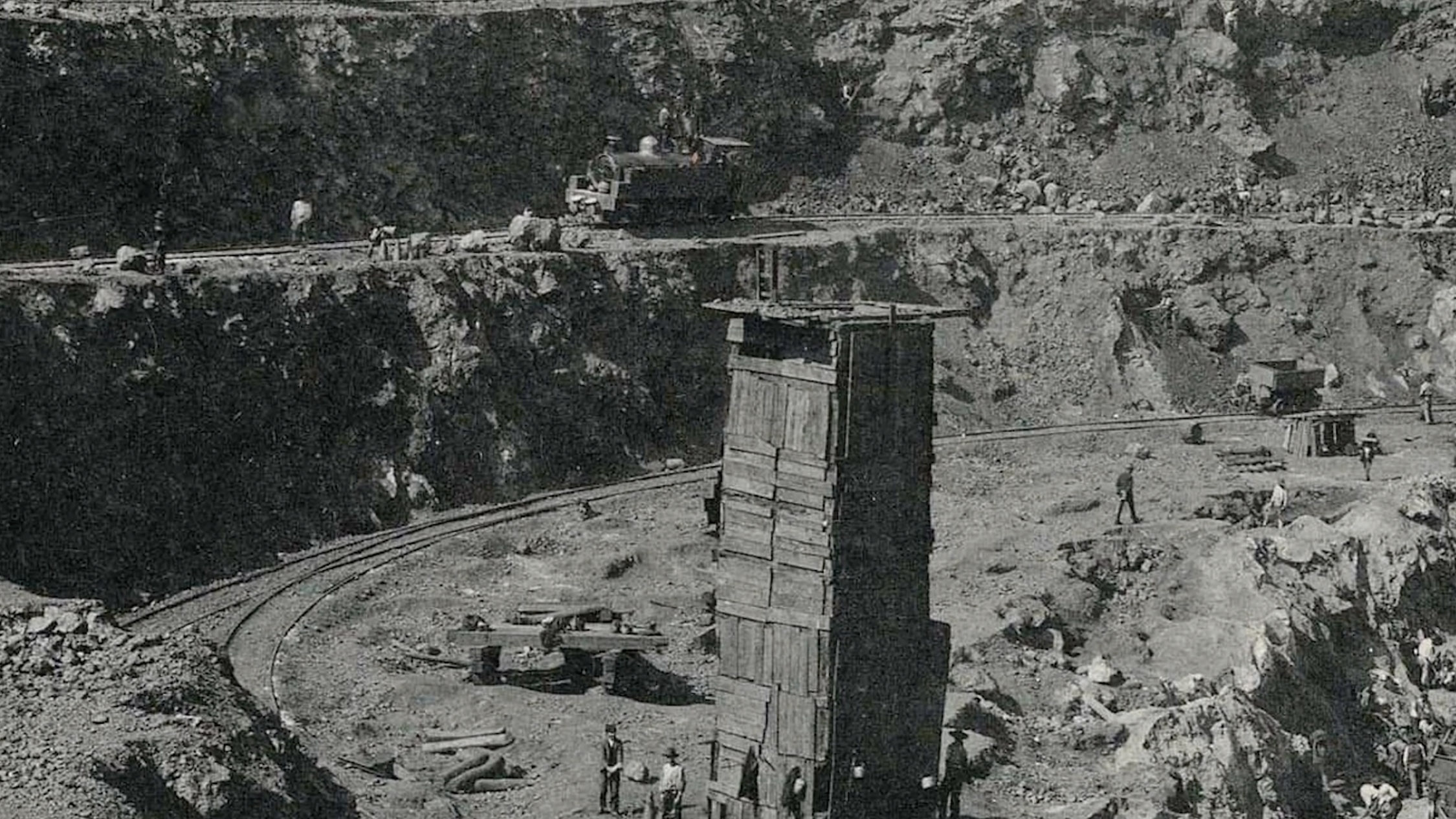

Nekya, a Film River (2023) is a full feature film that documents the geological traces of colonialism in Andalucia’s mineral record. The mines of Rio Tinto are some of the longest still-operating mines in the world with evidence of activity since the ancient Tartessians who would see the last moment of self-rule in the region. The film lays bare the role of extraction in the colonial process, its experiments and propagation from the red waters that flow into the Guadalquivir and into the open Atlantic – this is the source of the conquest of the Caribbean as well as the contemporary deterritorialized mining company, British-Australian conglomerate Rio Tinto Group. Language carries the name of a geological origin – this harsh terrain, one of earth’s analogues to Mars – a vital link in a planetary chain of violence, conquest, and pillage.

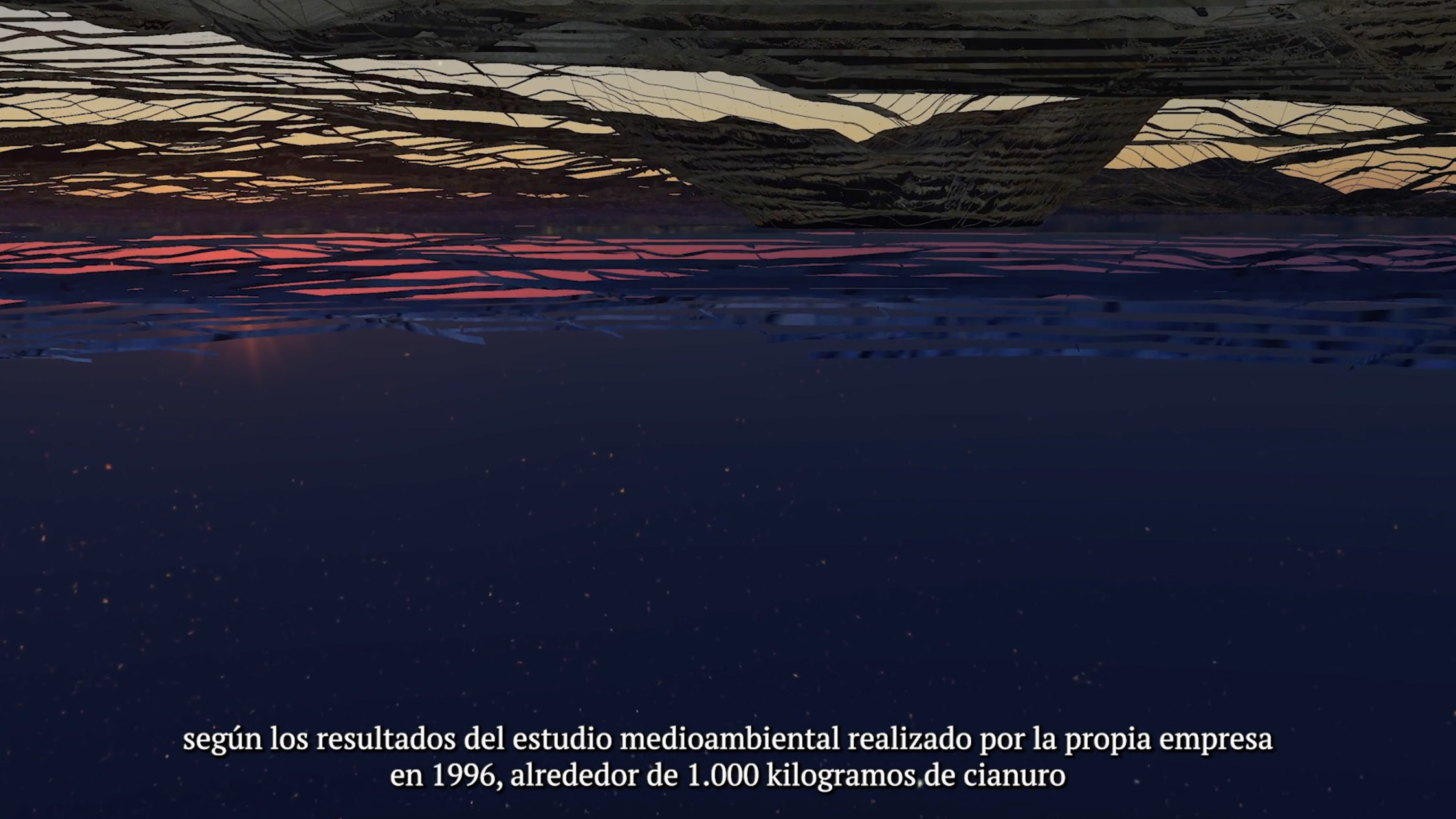

De Miguel’s film is a bricolage of poetic verses, documentary interviews, and historical investigation about what lies above and below the ochre soils northeast of Seville. It traces how this land became the location of Spain’s first ecological strike in the 19th century which ended in military guards opening fire against their own people to safeguard the interests of British capitalists, and how this model was exported from there to the territories of indigenous people from Canada to Australia. Today, the EU is supporting a new endeavour by Rio Tinto Group in to mine lithium for its planned green transition in Serbia, local activists groups have organised protests against the contamination of groundwater and adverse health effects for the local population. At a point of extreme ecological fragility, Río Tinto narrates our intertwined paths, chemical and biological, that relate exploitation of land and people to the nefarious politics of the few.

Regina de Miguel is known for her filmmaking and interdisciplinary artistic practice that combine research and the development of processes that result in the production of knowledge, films, and hybrid projects. One of the main discursive threads in de Miguel’s work is the critical analysis of the supposed objectivity of scientific devices of representation and the conditions of production of scientific knowledge. From a methodical approach, she establishes complex networks of connections that are nourished by the philosophy of science, ecofeminism, and speculative fiction and terror, which give rise to theoretical, existential, and poetic displacements where fragility operates as a form of resistance.

Solo exhibitions of de Miguel’s work include Arbustos de nervios como bosques de coral at The Green Parrot, Barcelona (2021); I´m part of this fractured frontier at C3A, Córdoba (2018); Aura Nera at Centro de Arte Santa Monica (2016), Barcelona; Ansible at Maisterravalbuena (2015), Madrid; and All knowledge is enveloped in darkness at Kunsthalle Sao Paulo (2014). Her filmography has been shown in numerous museums and institutions internationally and she recently contributed to the volume “140 Artists’ Ideas for Planet Earth” (2021), edited by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Kostas Stasinopoulos. Her work is held in several public and private collections, including the Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary and the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía.

Regina de Miguel was born in Málaga, Spain. She lives and works in Berlin.

Àngels Miralda (1990) is an independent writer and curator. Her recent exhibitions have taken place at Something Else III (Cairo Biennale); Garage Art Space (Nicosia); Radius CCA (Delft), P////AKT (Amsterdam), Tallinn Art Hall (Estonia), MGLC – International Centre for Graphic Arts (Ljubljana), De Appel (Amsterdam), Galerija Miroslav Kraljevic (Municipal Gallery of Zagreb), the Museum of Contemporary Art of Chile (Santiago), Museu de Angra do Heroísmo (Terceira – Azores), and the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art (Riga). Miralda wrote for Artforum from 2019-2023 and regularly publishes with Terremoto (Mexico City), A*Desk (Barcelona), Arts of the Working Class (Berlin), and is editor-in-chief of Collecteurs (New York).