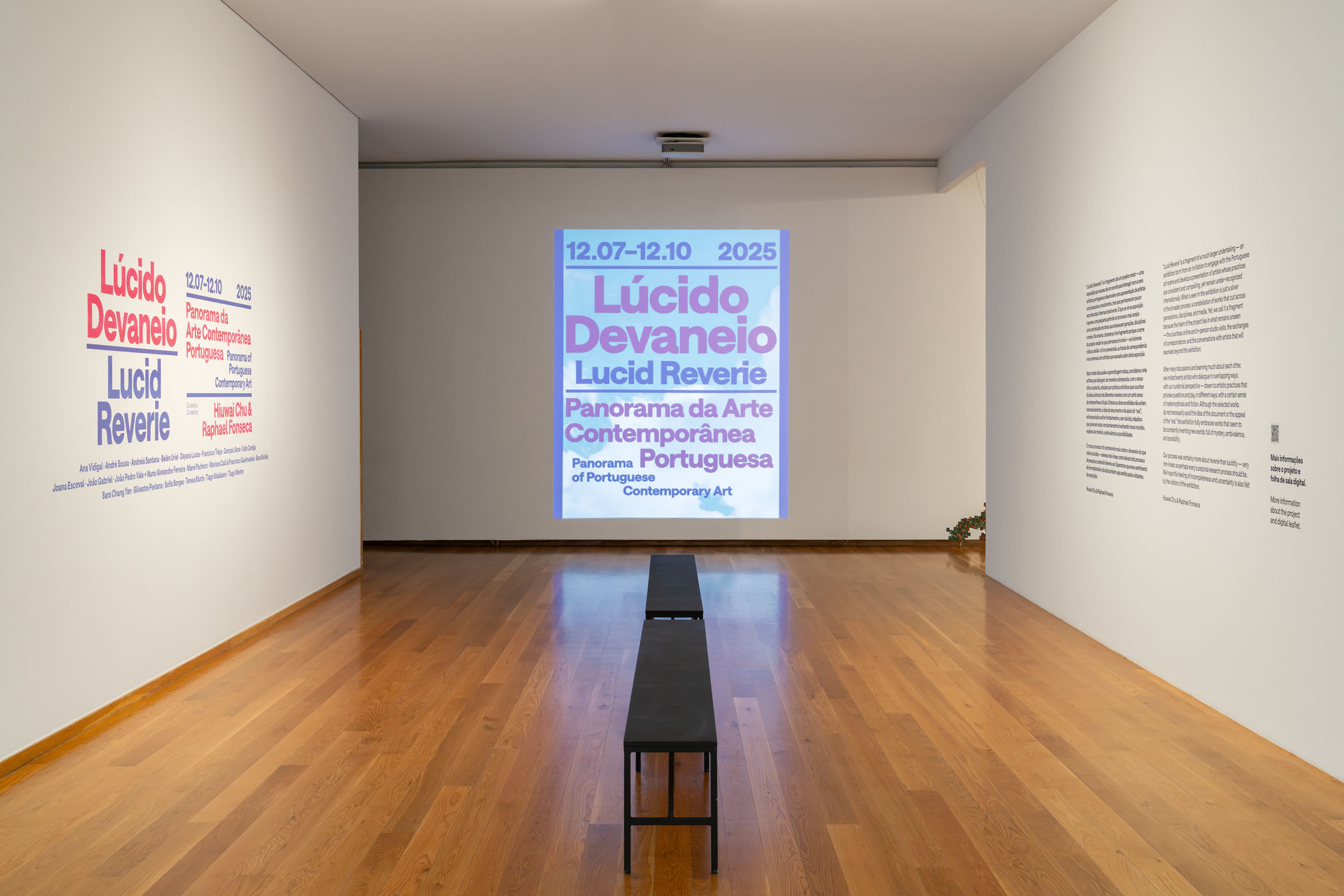

Lucid Reverie

Hiuwai Chu and Raphael Fonseca

Lucid Reverie is a visible fragment of a much larger undertaking — an exhibition born from an invitation by João Laia to engage with the Portuguese art scene and develop a presentation of artists with strong, consistent practices that remain under-recognized internationally. What you see in this exhibition is just a sliver of the broader process: a constellation of works that cut across generations, disciplines, and media. Yet, we call it a fragment because the heart of the project lies in what remains unseen, the countless studio visits and conversations with artists that will continue to resonate long after the exhibition takes form.

Our journey began in Porto at the end of April 2024. Since then, we’ve returned to Portugal multiple times, immersing ourselves in its art scene through exhibitions in museums, galleries, festivals, and independent spaces. We engaged in conversations with curatorial peers, but most importantly, we spent time with, we think, around a hundred artists — meeting in person and online, together and individually. We asked for portfolios and links for videos, talked about their works, the visual arts in general, and, of course, about life. This way, with lots of to-and-fro, we built a very peculiar and asymmetrical first-hand understanding of the contemporary artistic landscape of a nation that, just like any other, is an invention.

From the beginning, we knew that we didn’t want to approach the project by imposing an overarching theme and only seeking out artists who referenced certain ideas; instead, we tried to approach our conversations and studio visits with an openness that would allow us to establish natural links between areas of research and artistic sensibilities. Simply put, we wanted to work from the ground up and understand what is brewing on the western part of the Iberian Peninsula.

We met with artists born, raised, and that continue to work in Portugal, artists from elsewhere who have made Portugal their home, and Portuguese artists living abroad who retain strong connections to their homeland. Unsurprisingly, the range of practices we encountered was as diverse as in any other context — varied in approach and medium and varied regarding their underlying existential interests. Besides this diversity of approaches to how someone can still make images in the present, it was also essential to talk with artists from very different generations — from artists in their 20s, recently leaving university to analyzing estates of artists recently diseased, our process of research was, to say the least, porous. Any direction could, initially, be a direction.

Who shapes the Portuguese art scene? What drives these artists — what are their questions, concerns, materials, and modes of production? What does it mean to work in Portugal today? What are the advantages and constraints of this context? What pleasures and traumas do artists bring in their identity and/or territorial attachment to the country? How many Portugals are there inside Portugal? Do the artists living on the islands of Azores and Madeira have the same opportunities as those living in continental Portugal? Is it manageable to have a consistent career without moving to big cities like Lisbon and Porto?

We often ended our studio visits by asking the artists their opinions on the Portuguese art scene. Like a talk show interview, each artist gave us a different answer. Many artists discussed how “small” Portugal is, not only regarding its scale compared to other countries in the world, especially in Europe, but also small as an economy that, whether being powerful or not, never showed an interest to help foster its visual artists. Leaving Portugal and looking for an “international career,” for them, is not always a possibility, but often seen as something necessary; without it and international experience, it seemed impossible to make it happen as an artist in the country. Some artists had the privilege of studying abroad; others had the social ability to build an international network after specific invitations to be part of different projects. This fiction around the idea of being “international” is extensive — this could mean the United Kingdom, other European countries, the United States, or even other places in the Global South, like Latin America.

Another group of artists we talked to, even though they recognized the limits of having a professional career in the country, didn’t seem so anxious to have these international roots, being born, raised, and practicing in the country from a very young age seemed to give them a sense of experimentation and freedom that big artsy cities lack of. Staying in the country is not a matter of nationalist pride but can be seen as an act of resistance and a compliment to a specific idea of freedom. Whether this immense recognition will come one day is a matter of time and luck; the vital thing to some of them was having the time, space, and silence to keep working every day.

As the reader can imagine, the difference in answers and expectations around how the art scene in Portugal is seen by its artists is interesting and would certainly deserve a specific study and research in the future — especially when you look at the history of the region and see artists complaining about the lack of public investment, international recognition, and even working rights since the 16th century. An art scene is made not only of its artists and the images and discourses they produce but also of how these agents look and invent a particular opinion around their system — to learn about it was very anthropological and essential for our curatorial choices during this process.

Another critical and final layer of this project is our collaboration as curators. It began as a curatorial blind date, bringing together two individuals from different generations, cultural contexts, and professional trajectories, each with varying degrees of familiarity with the Portuguese scene. What united us was a shared curiosity and the perspective of outsiders looking in. This led to many conversations, debates, and discoveries — stretching across time zones and media — from a constant flux of WhatsApp messages to video meetings, at times the pleasure of meeting in person and deepening our inquiries together.

After many discussions and learning much about each other, we invited twenty artists who dialogue in overlapping ways, addressing notions of the body in its relation to history, memory, and our surroundings. Curiously, our gaze always matched our mutual interests towards artists’ practices that are not circumscribed, which open perspectives, and provoke questions and doubts, and that play in different ways with a certain sense of metamorphosis and fiction. This exhibition brings together artists that don’t necessarily avoid the idea of the document and the appeal of the “real” in a more sociological way but it undoubtedly embraces creators who seem to be constantly inventing new worlds full of mystery and ambivalence.

In hindsight — perhaps unconsciously, since this project started with an external invitation that deals with one specific geography, Portugal — could this selection of artists with practices that almost never make it clear their national belonging be a certain response to the fallacy of any curatorial project that has a national approach? Perhaps, but as our title states, when writing its text this perception comes as a lucid reverie.

Our process was certainly more about reverie than about lucidity — very non-linear, as perhaps every curatorial research process should be. We hope this feeling of doubt or ambiguity will also be felt by the exhibition’s visitors and by the readers of this publication.

PARTICIPATING ARTISTS

Ana Vidigal

Ana Vidigal’s (Lisbon, 1960) artistic practice spans painting, collage, assemblage, and installation, with research centred on memory, history, and the reconfiguration of both personal and collective narratives to generate critical new readings in the present. Vidigal’s visual language is one of layering and often incorporates found materials, transforming the act of collecting into a form of storytelling. Employing techniques of cutting and pasting, her compositions juxtapose the past and the present, the public and the private, the personal and the political.

André Sousa

André Sousa’s (Porto, 1980) expanded painting practice moves between sculpture and installation, abstraction and representation, and is part of a broader spatial and conceptual investigation that also engages with art history, mythology, and literature, as well as how images and abstract gestures accumulate meaning over time. For this exhibition, Sousa has created Apex, a towering structure in the form of a pyramid that reaches up to the ceiling of the Galeria. While monumental in scale, it also embodies the fragile qualities of a makeshift shelter, a recurring theme in the artist’s work.

Andreia Santana

With a practice focused mainly on sculpture, Andreia Santana’s (Lisbon, 1991) works are often marked by a minimalist approach that values form and texture, incorporating movement and action through the performativity of materials. Her sculptures tend to convey a sense of fragility and vulnerability while expressing a poetic force. Constantly experimenting with glass and associating the material with iron, fragility, ephemerality, and lightness are some of her central interests as a visual artist.

Belén Uriel

Belén Uriel’s (Madrid, 1974) practice is informed by the quotidian and our relationship to what she calls “universal” objects, and the concept of transformation, both in terms of meaning and materiality. By fragmenting and remodelling industrially produced items, her works deconstruct and rethink the social and cultural history of objects and our ever-evolving relationship with them. Helmets and backpacks are transformed into organic forms and beings, resulting in a hybrid between the known and the unknown, use and disuse, reality and fiction.

Dayana Lucas

Dayana Lucas’s (Caracas, 1987) work explores the intersection between drawing, sculpture, and spatial experience, treating artistic practice as both a physical and conceptual process. In this flow the act of drawing, emerges as form of invocation — an extension of movement, rhythm, and presence — offering unusual ways to engage with space through lines, markings, and erasures that suggest both presence and absence. Usually implicit, the body literally reappears in her photography work, where natural marks are combined with marks that adorn the skin.

Francisco Trêpa

Francisco Trêpa’s (Lisbon, 1995) work is characterized by a ceramic experimentation through different scales and chromatic explorations. Far from explicitly representing any animal or being studied scientifically, it is difficult not to look at his creations and not associate them with the many natural things that surround us. His previous works have already echoed flowers, larvae, eggs, and eggplants. Still, in his production and the one present in this exhibition, the certainty about the references to his ceramics is more blurred. Thorns, folds, and pores, sometimes in contrasting colours, are the basis of his research.

Gonçalo Sena

Working with sculpture and installation, Gonçalo Sena’s (Cascais, 1984) research addresses notions of identity, memory, and the relationship between human beings and the surrounding space. In this exhibition, the artist continues his interest in working with water in installation works and invites the public to enjoy it through the water’s sight, tactile stimulus and sound. Sitting on a bench designed by the artist, the viewer observes this kind of anticlimactic fountain and reflects not only on the limits between sculpture, installation, and design but also on the constant movement inherent in the dynamics of life.

Ilídio Candja

Ilídio Candja (Maputo, 1976) has extensive experience with painting and drawing. Playing with different scales that approach the monumental, the artist’s images are characterized by a texture that suggests the collage and the friction of elements extracted from different contexts, embodied on the same surface. For this exhibition, presents the installation “Ujamaa,” which plays with the word from the Makonge language – spoken in southern Tanzania and northern Mozambique – that can be translated as union, unity, and/or family. By using this word as a title, Candja reflects on the idea of unity in his work and in his approach to thinking about painting in series.

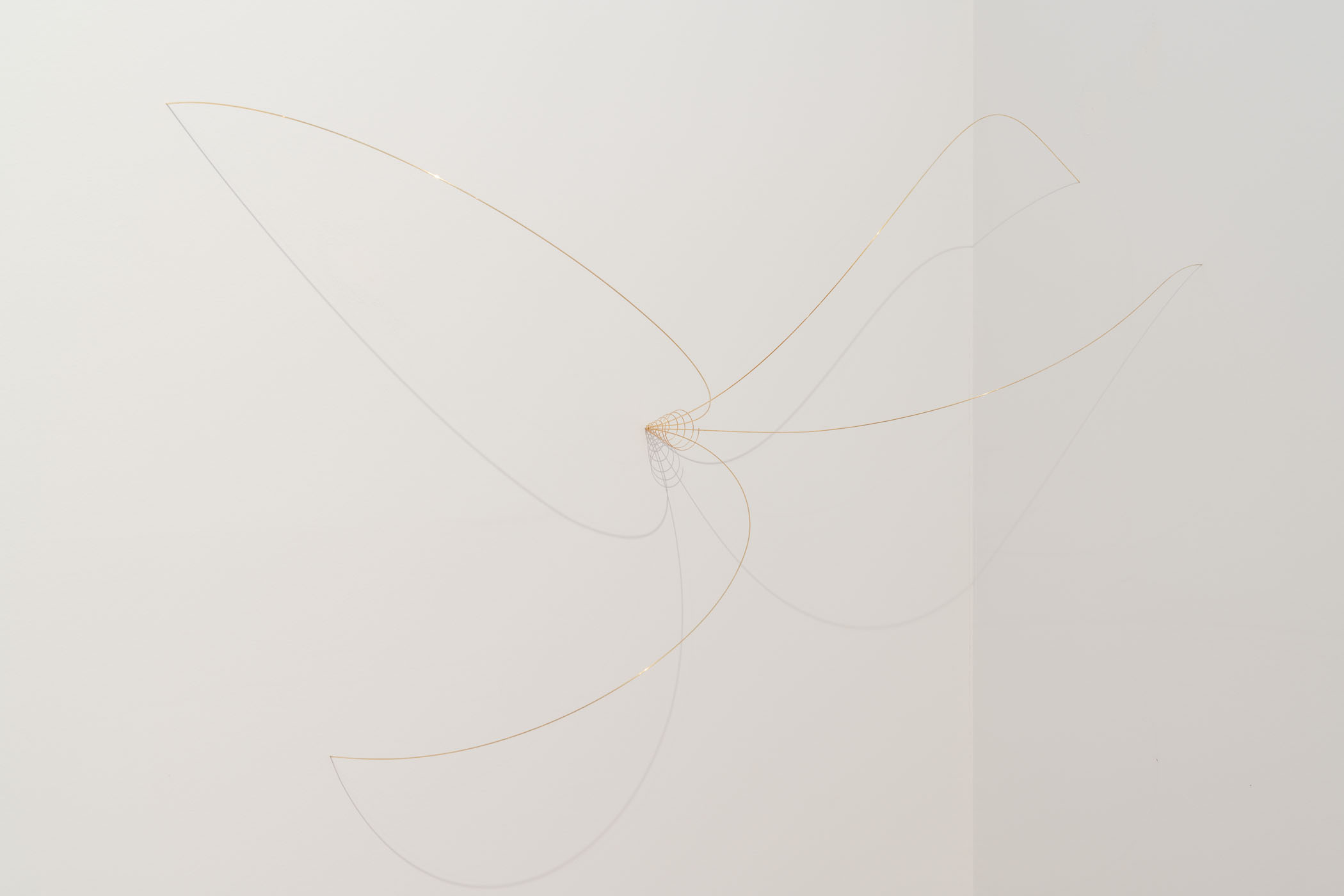

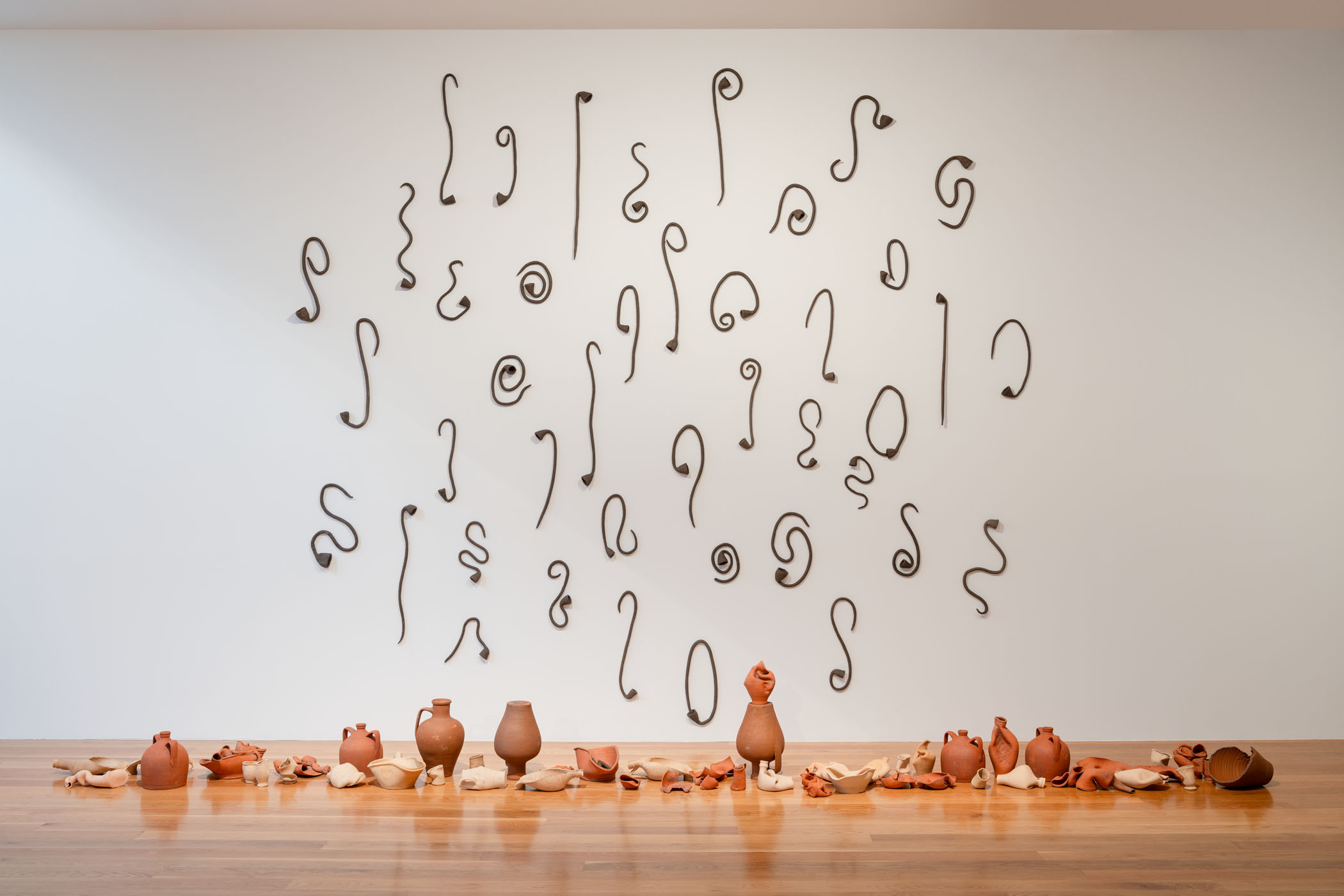

Joana Escoval

Joana Escoval’s (Lisbon, 1982) research addresses the intersection between space, matter, and sensory perception. Using various media, including installation, sculpture, and drawing, Escoval creates experiences that invite the viewer to interact and reflect on the space they occupy and her works often suggest transformations of different scales in the exhibition space. As in the works selected for this exhibition, many of her works are composed of simple lines that suggest spirals, asterisks, and other forms, showing the viewer the importance of agglutination and dispersion in the visual arts and life.

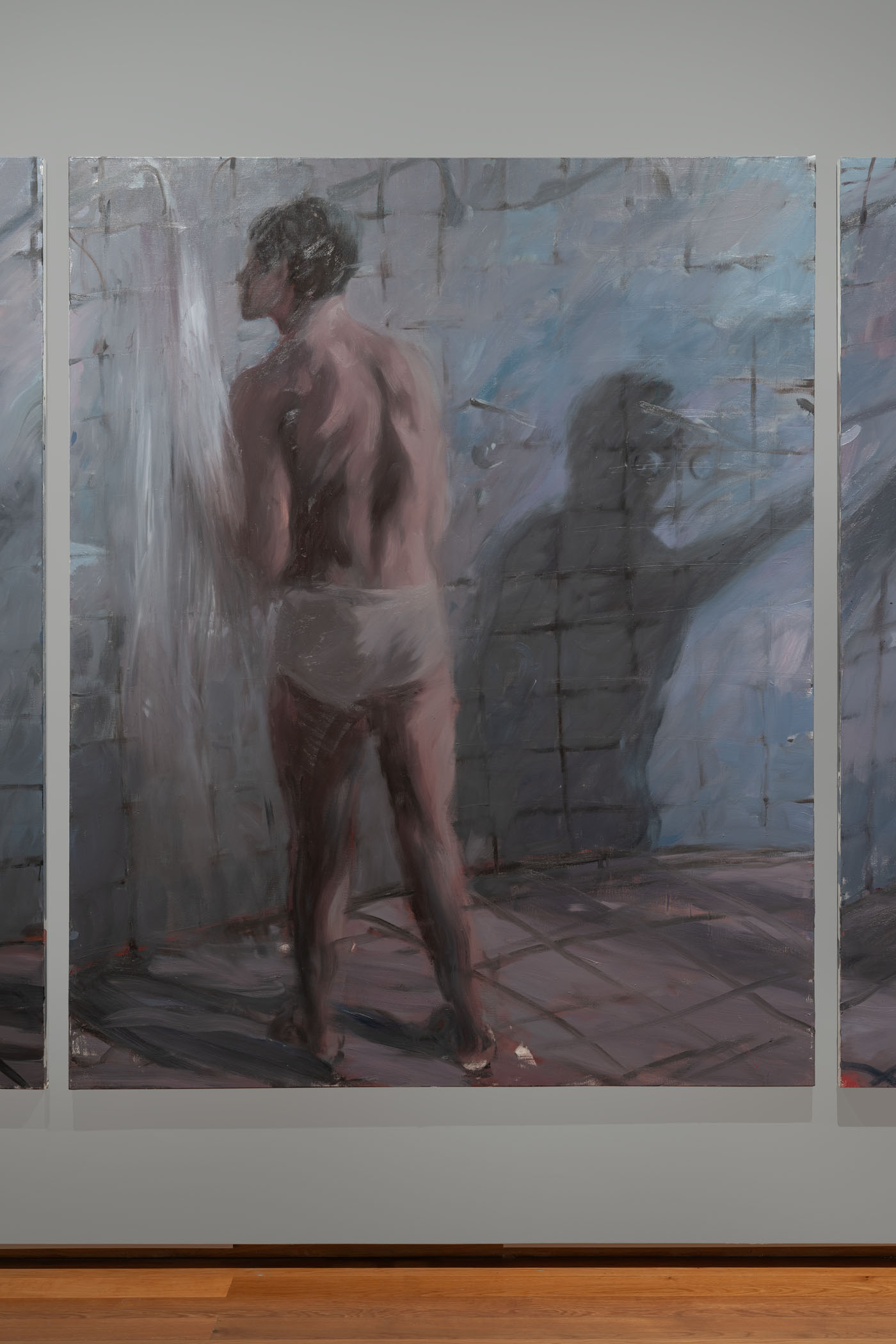

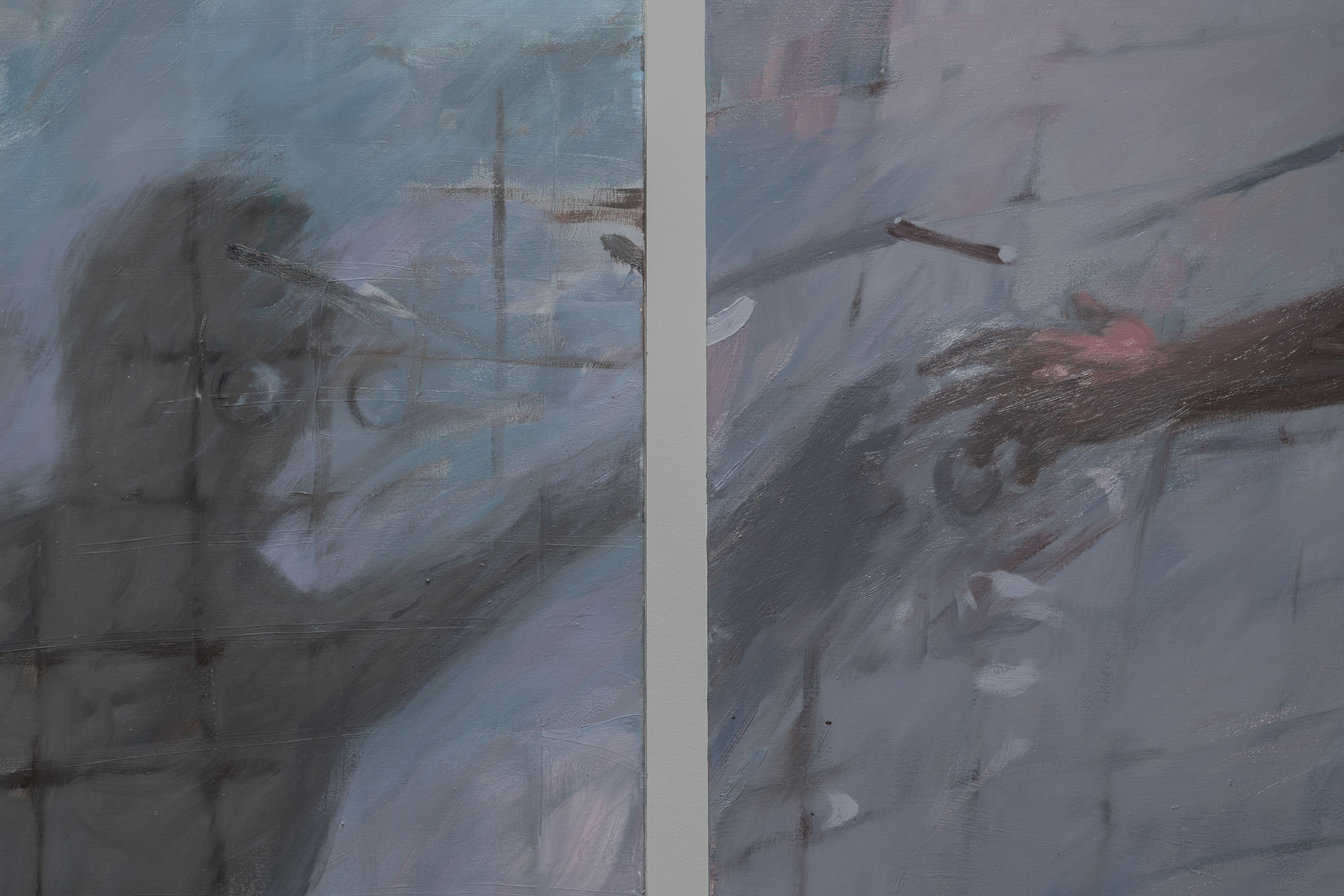

João Gabriel

Dedicating himself exclusively to painting, João Gabriel (Leiria, 1992) explores the complexity of identities and human relationships, often incorporating elements that resonate with queer narratives and their nuances; the human figures in his paintings are usually depicted as if they were in a state of suspension. Like frames taken from a film — a working method that the artist used for part of his career — the figures in his images suggest interruptions in actions that leave the viewer full of doubts. Whether in sexual acts, intimacy, or contexts that seem to surround flirting and cruising, his images exude desire but also retraction.

João Pedro Vale + Nuno Alexandre Ferreira

João Pedro Vale (Lisbon, 1976) and Nuno Alexandre Ferreira’s (Torres Vedras, 1973) collaborative practice explores themes of identity, popular culture, history, and social constructs. Employing a multidisciplinary approach, their work often blends elements of fiction and reality to challenge dominant narratives, reclaim marginalized histories, and provoke discussions on belonging, resistance, and social transformation. Climacz revisits the first public Gay Pride celebration in Portugal in 1995, focusing on the now legendary party that took place at the Climacz nightclub in Lisbon. More than a tribute, this installation is a meditation on the intersection of art, activism, and LGBTQIA+ history, affirming the power of communal spaces in fostering resistance, expression, and queer identity.

Mané Pacheco

Mané Pacheco’s (Portalegre, 1978) research is marked by creating organic elements and diverse textures, creating compositions that evoke nature and urban culture. This fusion of influences allows her pieces to interact with the surrounding environment, endorsing their site-specific character and highlighting the versatility of Pacheco’s practice, where the desire to create a formal and material vocabulary expands and escapes repetition. Violence, seduction, and fetish go hand in hand in a visual aspect that invites us to dwell on its details, appealing to the human senses in such a way that the desire to touch these pieces becomes inevitable.

Mariana Caló & Francisco Queimadela

Mariana Caló (Viana do Castelo, 1984) and Francisco Queimadela (Coimbra, 1985) are an artistic duo whose work is centered on the audiovisual media and its many repercussions in related media. Their practice explores the limits between the body and the landscape, always in a broad reading key where words usually play an important role in the viewer’s enjoyment. In “Phantom Flower,” the artists play with the silhouettes of different flowers and their phantasmatic characters endorsed by black-and-white projections made with slides. Floating in space, these images invite us to consider the relationships between anatomy, botany, and zoology beyond their scientific limits.

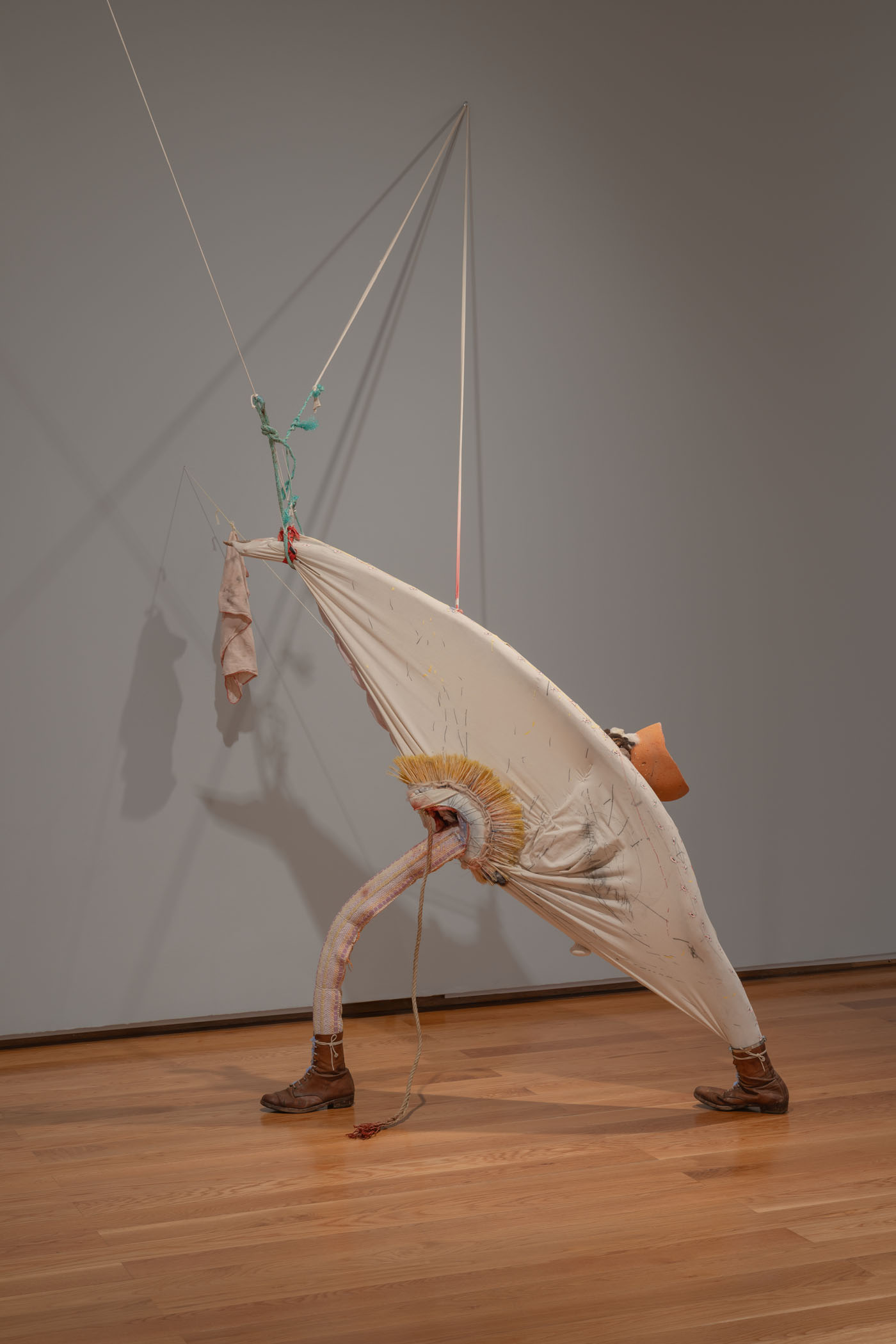

Sara Bichão

Sara Bichão’s (Lisbon, 1986) practice is infused empathy and care. Made with found and repurposed materials, her sculptures are lovingly assembled to form new relationships between objects that transcend time, as well as social and cultural constructs. Each piece is a patchwork of assorted materials, interwoven with a layering of their varied histories, which are strengthened by their togetherness. Although the objects and forms in her sculptures may at times be recognizable, their thoughtful reworking conjures otherworldly imaginaries, transporting us to a mythical realm where hierarchies dissolve and new characters and energies emerge.

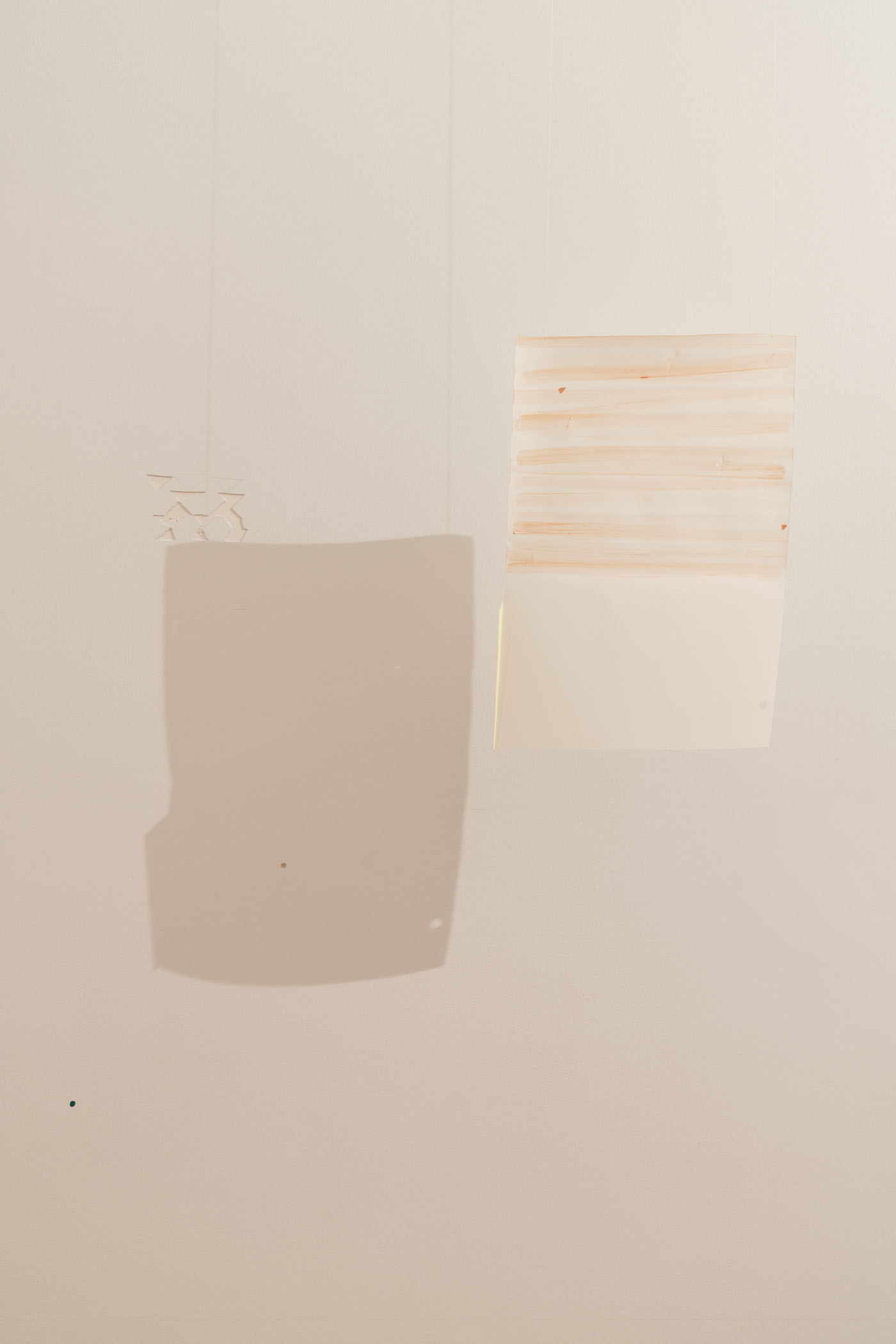

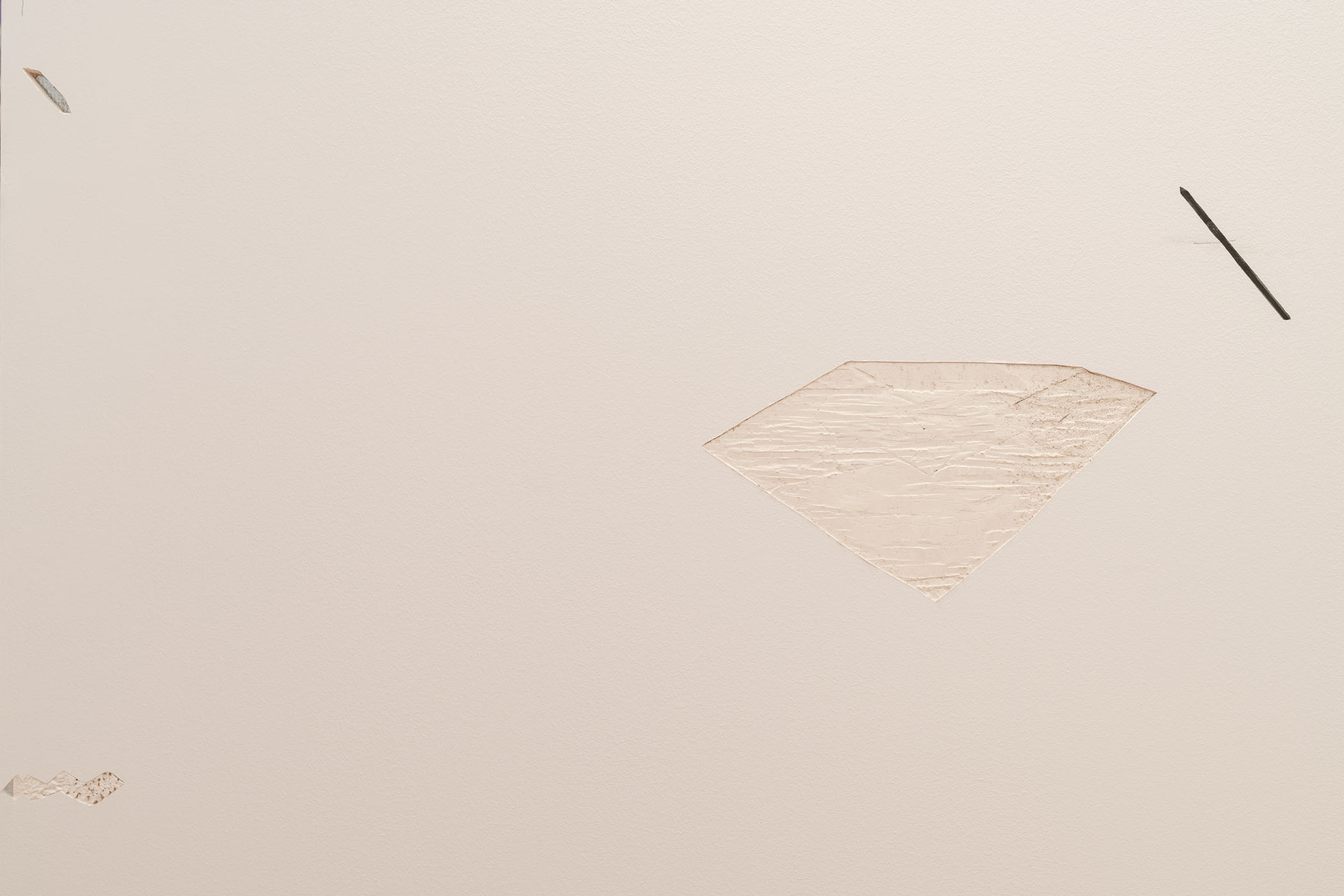

Sara Chang Yan

Working across painting, drawing, video, and installation, Sara Chang Yan’s (Lisbon, 1982) artistic practice is a contemplation of space, form, and perception. Her works are delicate choreographies of geometries arranged with playful precision and subtle gestures that capture the synergies between presence and absence, transparency and opacity in which negative space takes on equal importance as the forms that occupy the canvas. Yan is an orchestrator of forms, situating elements in dialogue with one another and their surroundings, including light, shadow, air, and the viewer—all becoming integral to the meaning of her works and activating our own sensorial engagement with space.

Silvestre Pestana

Silvestre Pestana’s (Funchal, 1949) practice spans poetry, performance, video, and digital media. Working with experimental literature and its visual and technological explorations, His works challenge conventions, questionning the relationship between language, the body, and new media. Visual poetry has been at the core of his practice, where he has deconstructed language and experimented with typography, creating compositions that blurred the line between writing and image. Amplifying his long-standing interest in words and cybernetics, Terras Raras consists of 7 commercial LED panels where illuminated words flash across the screens in vivid colors and bold designs, serving as prompts for reflection.

Sofia Borges

Time is a significant protagonist in Sofia Borges’ (Lisbon, 1971) filmmaking, where moments with no spoken words hold as much weight as those with speech. The films 53 and Súlu S’Aua (The Water Spirit) navigate the intricate layers of colonial history on the island of São Tomé and Príncipe, specifically tackling the enduring trauma of the Batepá Massacre. Her works are acts of resistance that employ unconventional narratives and cinematic gestures that reclaim agency, resituate historical trauma, and emphasize the persistence of memory in looking at the past, while also helping to shape the present and future.

Teresa Murta

Working exclusively with painting, Teresa Murta’s (Lisbon, 1993) works invite long contemplations. Dealing with varied scales, the artist is interested in creating images permeated by mystery that do not deliver any literalness to the viewer’s eyes. In the last years, her compositions have moved from a clear relationship between figure and background, to an apprehension of the surface of the canvas where everything seems more flat and connected. If before we saw organic forms that ghostly ended with identifiable objects on a background of another tone, now we notice a greater abruptness in her brushstrokes and an interest in creating clouds of color with a detail never seen before.

Tiago Madaleno

Tiago Madaleno’s (V. N. de Gaia,1992) artistic practice is research-based and furthered by an endless exercise of free associations. Ivy has been a symbol of intellectual achievement since Roman times and is also associated with fidelity and eternal life and is the central element in the installation “Autumn Correspondences”. In the plant world, it is known for its rapid growth and its ability to traverse barriers such as walls or fences. This ability to travel and transcend worlds is precisely why Madaleno is interested in ivy and uses it as a metaphor to reflect on ideals, lost landscapes, obsessions, and desires for escapism.

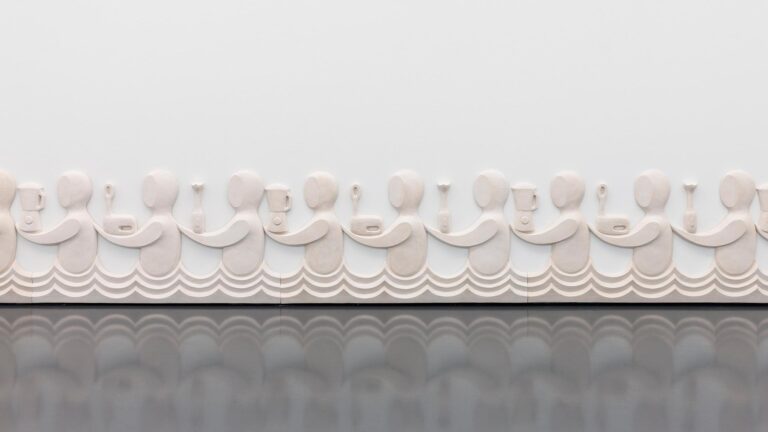

Tiago Mestre

Tiago Mestre’s (Beja, 1978) research has an experimental and investigative approach, where he investigates the properties of materials and how they relate to space and the viewer. Mestre’s works often explore the notion of transience and metamorphosis, using forms that seem to be in constant transformation. This perspective has a poetic character while at the same time provoking an appreciation of the fragility and, often, impermanence of things. Frequently using clay, bronze, and plaster in recent years, his work moves between a direct dialogue with sculpture and modernist traditions of making and showing.

***

Raphael Fonseca was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and now lives in Denver, USA, where he works as a curator of modern and contemporary Latin American art at the Denver Art Museum. He is the chief curator of the 14th Mercosul Biennial (2025) and is also part of the curatorial team for the 3rd Counterpublic Triennial, which will take place in St. Louis, United States, in 2026. He was also co-curator of the 22nd SESC Videobrasil Biennial (2023), and an advisor to the Prospect 6 triennial in New Orleans, United States, in 2024. Recently he curated Fullgás: visual arts and the 1980s in Brazil (Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2024); The awake volcanoes: Sandra Vásquez de La Horra (Denver Art Museum, 2024), Who tells a tale, adds a tail (Denver Art Museum, 2022); Raio-que-o-parta: fictions of modern in Brazil (SESC 24 de Maio, São Paulo, 2022), Sweat (Haus der Kunst, Munich, Germany, 2021) and To-and-fro (Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, São Paulo, Brazil, 2019). Fonseca was included in ArtReview magazine’s list of the 100 most influential people in the visual arts globally in 2023 and 2024.

Hiuwai Chu was born in Guangzhou, China, and now lives in Barcelona. She studied anthropology at Barnard College, Columbia University, New York (1996). In 2021 she was appointed Head of Exhibitions at the MACBA Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona. As an exhibition curator there since 2016, she has put together shows including Charlotte Posenenske: Work in Progress(2019), Undefined Territories: Perspectives on Colonial Legacies (2019), Akram Zaatari: Against Photography; An Annotated History of the Arab Image Foundation (2017) and Andrea Fraser: L’1%, c’est moi (2016). As an assistant curator at MACBA (2007–2016), she worked on exhibitions with artists such as John Baldessari, Rita McBride, Lawrence Weiner, The Otolith Group and Raqs Media Collective. In 2020 she joined the board of Hangar (Barcelona). Chu was production coordinator for the Catalan Pavilion at the 2009 and 2011 editions of the Venice Biennale and gallery manager at Kowasa Gallery, Barcelona (2003–2006). Before moving to Barcelona, she was associate editor at the Aperture Foundation, New York (1999–2002).