Lin May Saeed’s (1973–2023) solo show “Untouchability”, curated by Povilas Gumbis, runs at Sapieha Palace in Vilnius until 31 December.

‘You don’t just touch something once’, observed the German–Iraqi artist and animal rights activist Lin May Saeed (1973–2023). This statement, part of a broader commentary on her creative process, serves both as an enigmatic introduction to Saeed’s exhibition on the 1st Floor Northern Gallery of Sapieha Palace and as a conceptual summary of the works on view – a fragment of her artistic legacy. Saeed’s creative and personal ambition to renounce an anthropocentric relationship with non-human life raises the question of the limits of human possibility and of humanity itself. In her artistic practice, this manifests through sustained and attentive engagement with matter and through a consistent rethinking of the depiction of humans, other animals, and their relationship, drawing on ancient traditions of representation while always imagining a more just future. The sculptures, reliefs, paintings, and drawings in the exhibition embody this idea – emphasising touch as the charged centre of encounter between the works and their viewers.

The senses of most animals are conventionally divided into five faculties – sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch – yet all of them, not just the last, are grounded in contact: sight arises when a beam of light strikes the retina; hearing begins with the vibration of the eardrum caused by sound waves; smell and taste are triggered when molecules come into contact with their respective receptors. Contact may be considered the foundation of the sensory structure – the condition for any encounter, the threshold that marks the boundary between inside and outside, between the self and the Other.

In the context of continuous interaction with the environment, contact is always more than a purely sensory function – it is touch in a broader sense: a metaphor for the temporal unfolding of the relationship between self and world, the basis of being and of knowing. In the constant flux of meaning, touch opens itself to indeterminacy: in trying to touch, we grasp only the surface; in relation to the Other, we acknowledge the unbridgeable gap that opens between us. Yet this is not a failure of connection but, rather, its ethical condition. Every touch carries within it the paradox of untouchability – closeness arises not by eliminating distance but by preserving it. Like holding hands: an intimate physical contact that seems to erase the division between two bodies but in fact exists only because of the thin line that separates your skin from the Other’s. Were this boundary to disappear, the bodies would fuse into an undifferentiated mass, and the very act of touching would cease to exist.

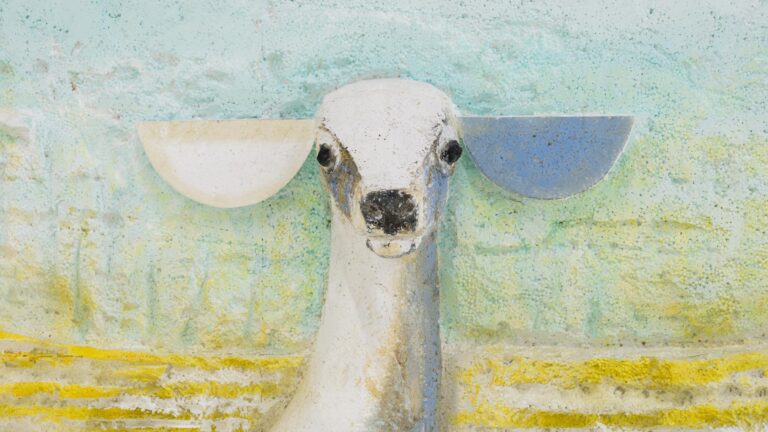

In rethinking the depiction of animals, Saeed does not aim to render them unrecognisable – the animals remain identifiable, yet through the inflection introduced by the artist they also become estranged, slipping away from the comfort of a familiar gaze. This opens up the possibility of speaking about an e(ste)thics of untouchability that resists culturally established norms of human perception and behaviour. At the same time, her approach challenges the unwritten rules of exhibition etiquette, inviting physical contact with the works and producing an experiential tension between attraction and repulsion.

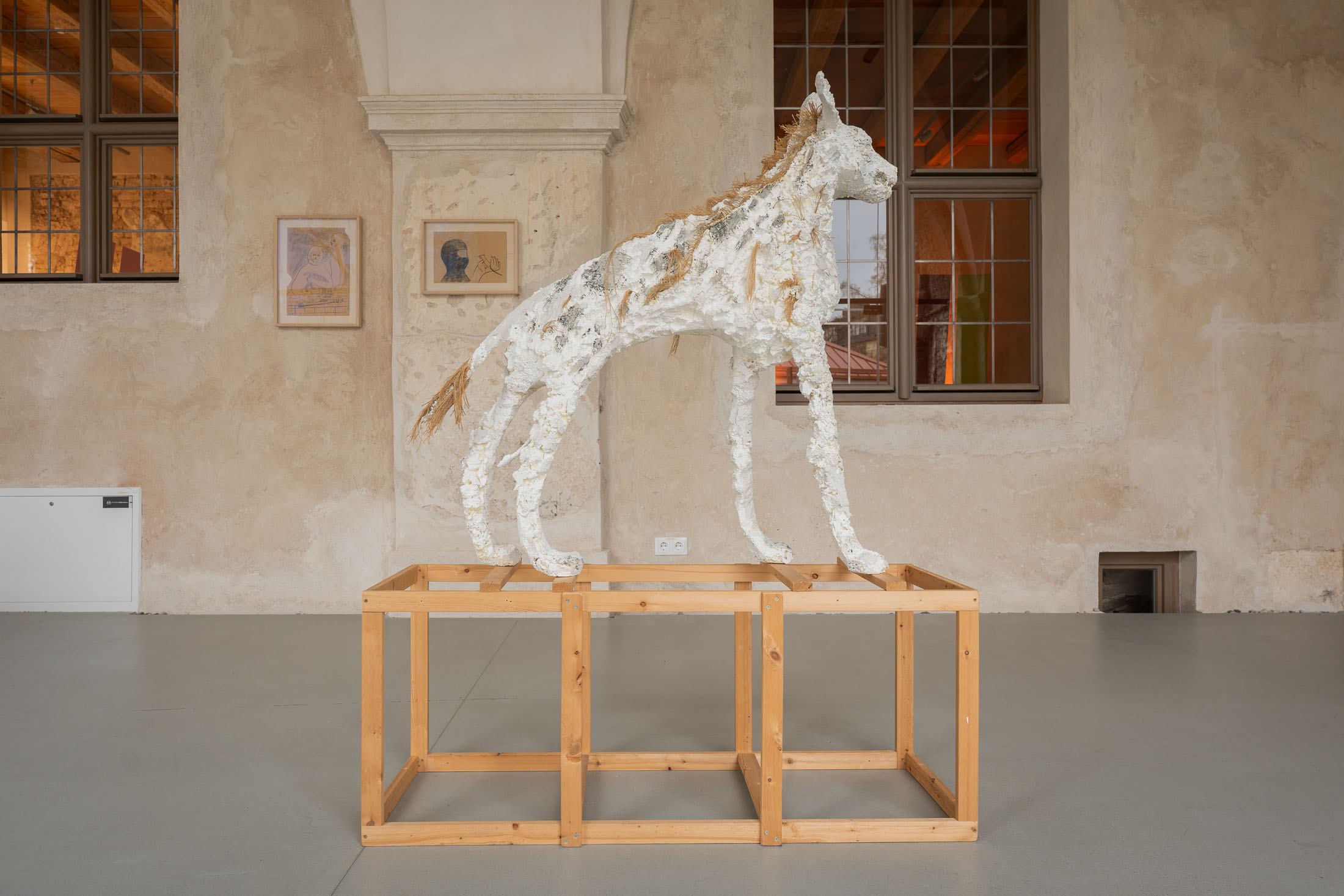

The very materiality of Saeed’s works unsettles conventional notions of distance. For her sculptures and reliefs, she turns to polystyrene, commonly found in hardware stores as insulation and sealing material. Though prone to crumbling into particles when handled carelessly, it is at the same time unnaturally durable: resistant to decay, it can persist for decades. This contradiction reveals its problematic status – born of fossil fuel extraction, toxic in composition, and burdening the future with its virtually imperishable presence. As Saeed herself observed, such a material should not exist at all.

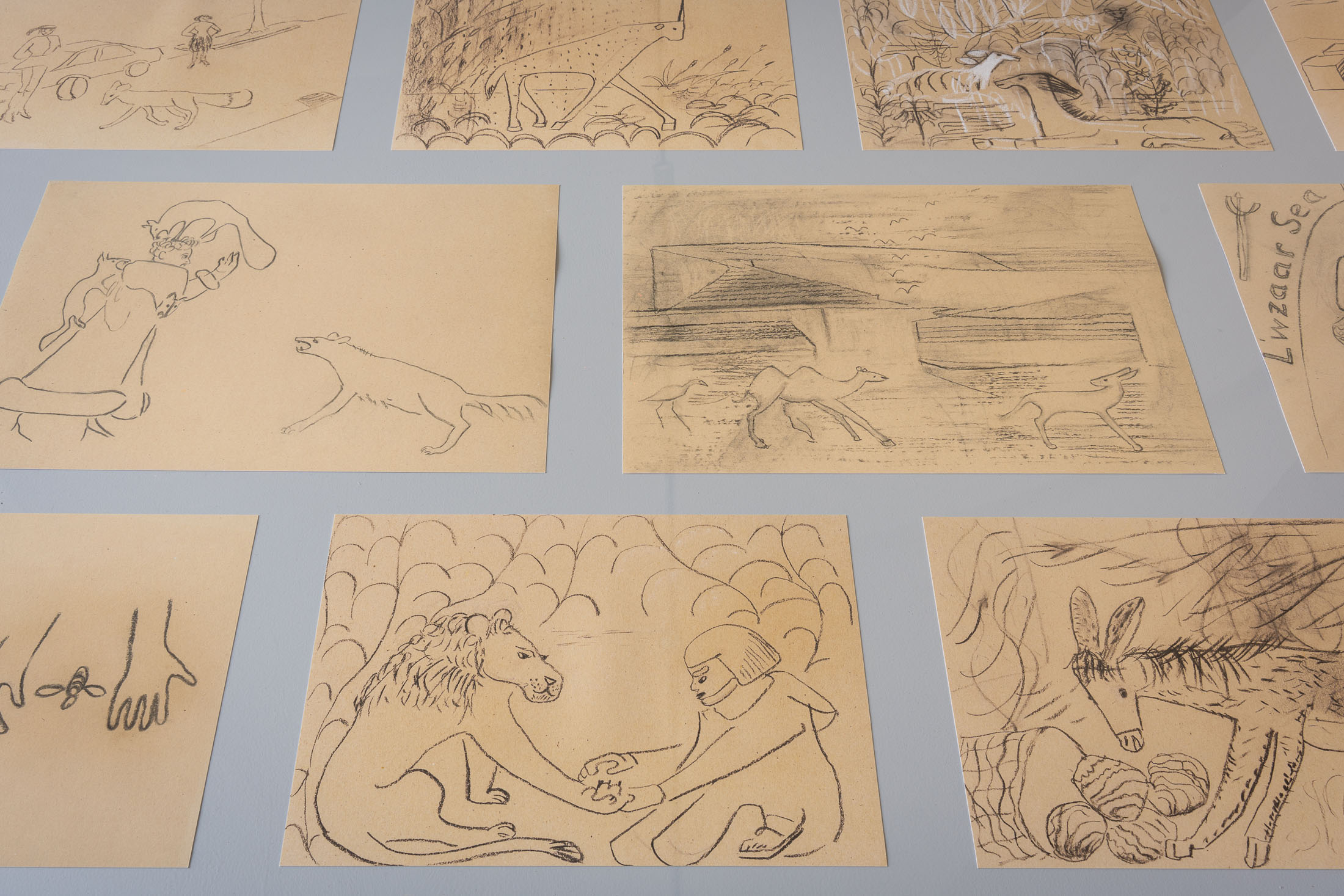

Without shying away from these contradictions, the artist mobilises polystyrene as a marker of contemporaneity, speaking openly of our time and of the ambivalent nature of technological progress. The surfaces of her sculptures and reliefs, furrowed with recesses and protrusions, testify to a cautious touch and a meticulous working process that responds to the fragility of the material while disregarding its repellent qualities – its roughness, harshness, and electrostatic cling. Through creative reworking, the material is endowed with aesthetic value and unfolds across a broad temporal spectrum: from reflections on the present to references to Mesopotamian legacies – a scene from Epic of Gilgamesh represented in Enkidu and Jackal (2007), or relief traditions recalling the Ishtar Gate that once encircled Babylon, as well as the massive Lamassu figures that stood guard over the Sumerians. It also gestures towards Antiquity and the Renaissance, evoking both the polychromy intrinsic to classical marble sculpture and the whiteness retrospectively idealised by later traditions. At the same time, the animals poised on hollow wooden constructions – a symbolic gesture of species liberation – echo the modernist critique of monumental sculpture, which rejected the hierarchy of the pedestal and the cult of the idol. The chain of time culminates in the future: in utopian visions of interspecies solidarity and empathy, or in post-dystopian alternative realities in which animals, left without humans, live on with their legacy.

In Saeed’s own words, ‘[Animals] are so much “the Other”, especially in man-made, predominantly monospeciesist urban environments. Trying to grasp the space between me and an animal, something opens up like a journey through time.’ The layered temporal references encoded in polystyrene speak of unknowability and resist the fixation of meaning. Like Saeed’s animal figures, they pause together with the viewer at the threshold of touch, charged with transgressive tension: between polystyrene – fleeting in its use but nearly permanent in its material presence – and the animal form, with which humans have maintained practical and mythical relations for millennia; between untouchability and the anticipation of connection; between fragility and the risk of damaging contact with a delicate artwork. This tension is not merely aesthetic or experiential – it is also political: it asks who may count as a subject; who is included within the field of legal visibility and protection; and who is left at the margins of the political fabric.

– Povilas Gumbis

Lin May Saeed studied at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf and co-founded the Project Space Center in Berlin. Prior to the postmortem tribute dedicated to her in 2024 concurrently by GAMeC, Bergamo, and the Biennale Gherdina, Ortisei, Saeed exhibited at the Georg Kolbe Museum, Berlin (2023), Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts (2020), Studio Voltaire, London (2018), and Lulu, Mexico City (2017). She featured in group exhibitions at Manifesta 15, Barcelona (2024); Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden, Germany (2023); Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Turin (2021); M HKA – Museum of Contemporary Art, Antwerp (2021); Aspen Art Museum, Colorado (2020); Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2019); the Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts (2019); Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt (2018); mumok – Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Vienna (2018); and Köln Skulptur, Cologne (2017).