Artist: Lewis Hammond

Exhibition title: Rising and Falling (While We Were Sleeping)

Venue: Huset for Kunst & Design, Holstebro, Denmark

Date: November 27, 2021 – February 20, 2022

Photography: ©David Stjernholm / all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Huset for Kunst & Design, Copenhagen

Note: Exhibition floor plan is available here

Lewis Hammond (UK), RISING AND FALLING (While We Were Sleeping)

Written by Laura Smith, Whitechapel Gallery, London

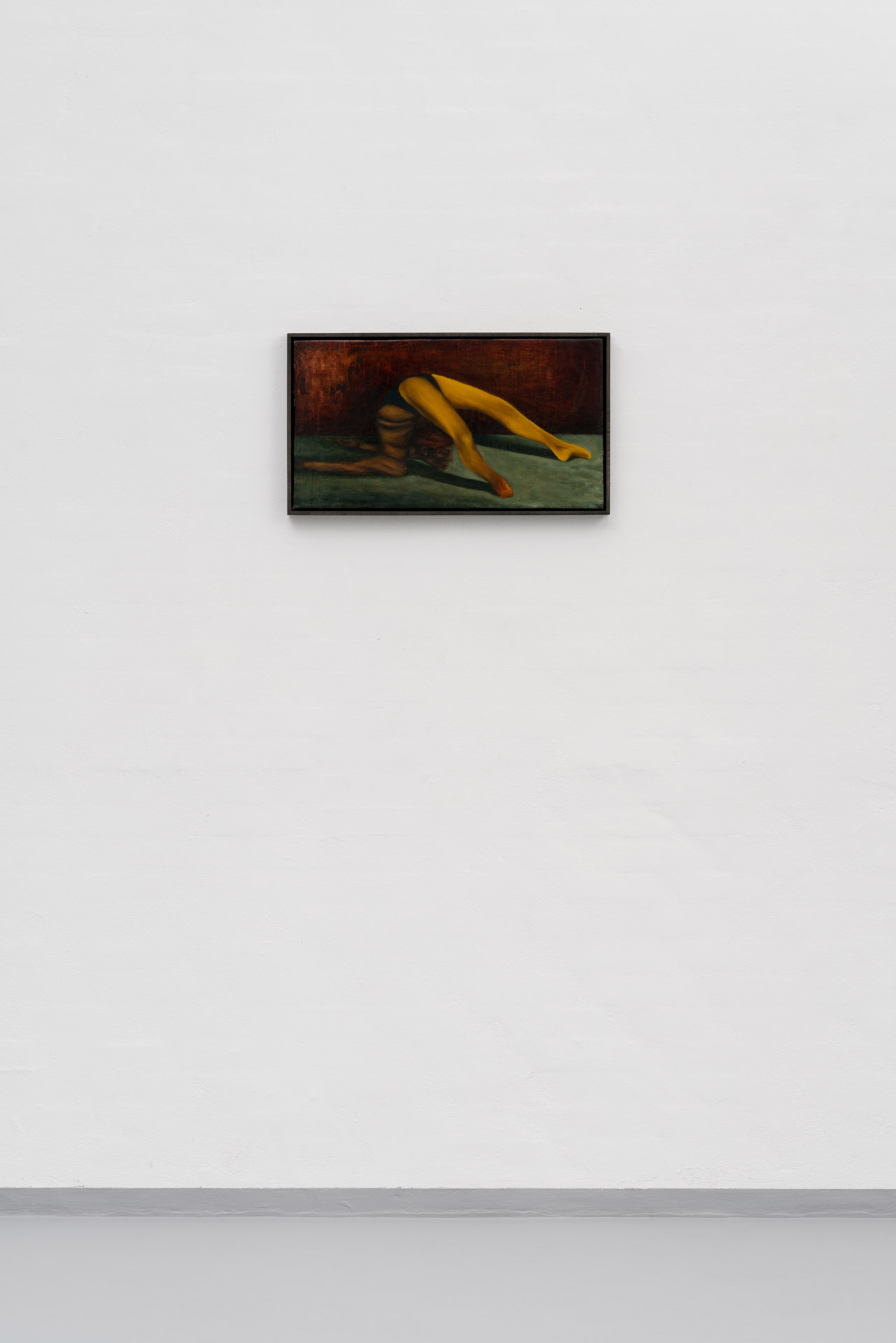

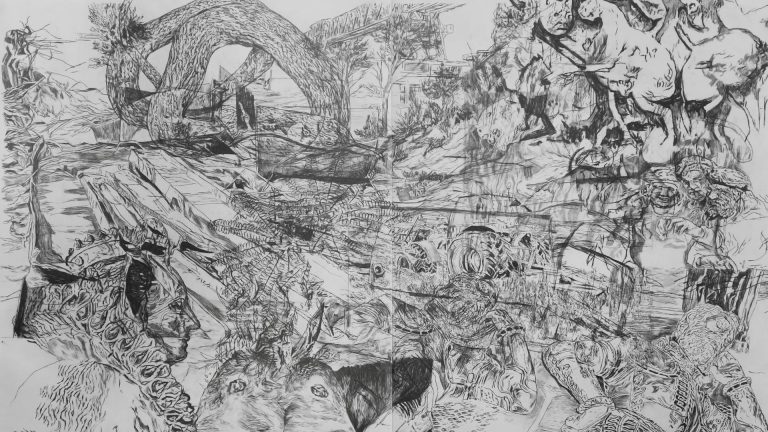

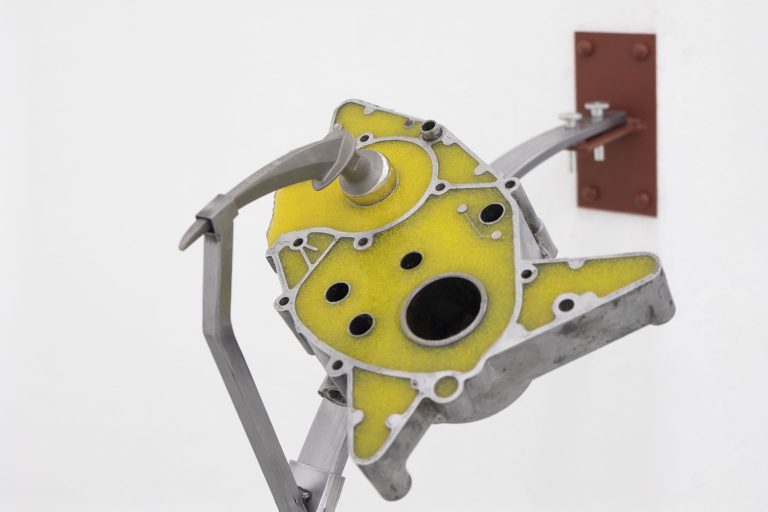

A coterie of isolated bodies, seemingly untroubled by the presence of a viewer, lurk in the claustrophobic dusky rooms or bleak landscapes of Lewis Hammond’s paintings. Accompanied by occasional natural elements – slightly-too-big stars, ominous clouds that could also be waves, creeping thistles and thorny roses, even an out-of-place porpoise – Hammond’s works are composed of textures. Liquids, skins, shadows, drapes and reflections grant them a slippery surreal timelessness that is also wholly contemporary, sliding between metaphorical analogies and discordant physical realities. The untimeliness of the works is in part due to their velvety, fluid surfaces and their subdued palette, as well as to the subject matter of some, in which demons, gargoyles and other nightmarish beings morph or skulk into depictions of people.

Many of the paintings that Hammond has made for this exhibition find unsettling and inadvertent resonance with Daisy Lafarge’s brutal and bright collection of poems, Life Without Air (2020). Both are compassionate, intimate and ecologically and politically nuanced. One poem in particular, Dredging the Baotou Lake considers a lake in Inner Mongolia that has been completely poisoned by the mineral mining that feeds modern technologies. An abiding feeling of airlessness fills the poem, the same feeling also seeps through Hammond’s prescient, cinematic paintings, which connect aspects of his own biography with art historical, biblical and mythological references, as well as pop, punk and even BDSM clothing allusions (for example in his earlier work, Host, 2017). By combining his personal history with an astute appreciation of art history, particularly the work of Caravaggio, William Blake, Francisco Goya and Jusepe de Ribera – Hammond creates what he calls ‘sideways reflections on life’s complexities.’

These sideways reflections build strange worlds and distorted narratives in which his subjects, who embody different psychological states – angst, sorrow, melancholy, confusion… but also hope, resolve and contemplation – seem to find themselves in an ever elusive quest for salvation. As Hammond himself comments: ‘the work sometimes references the shared global panic of our times. We live knowing our natural resources are finite; feeling the impact of climate change; seeing how small events can cause a devastating reverberation across the planet. This is something that has always been in my work, but of course is possibly more pronounced at times like these, when the whole world is acutely aware of the precarious state we are in.’

As an anti-fascist and often nature-orientated movement, surrealism originally grew out of the horrors of the First World War and the angst of the 1920s. So it is not surprising that Hammond might signal toward its aspirations through his aesthetic sensibilities today. Surrealism’s emphasis on dreams and the subconscious affects of trauma also seem to find fertile ground in Hammond’s close architectural spaces that exist neither in day nor night but rather a kind of perpetual twilight. The title of the exhibition too, While We Were Sleeping, suggests either an entire dreamscape of characters and narratives, or the bleary realisation of having missed something, or, missed being able to stop something.

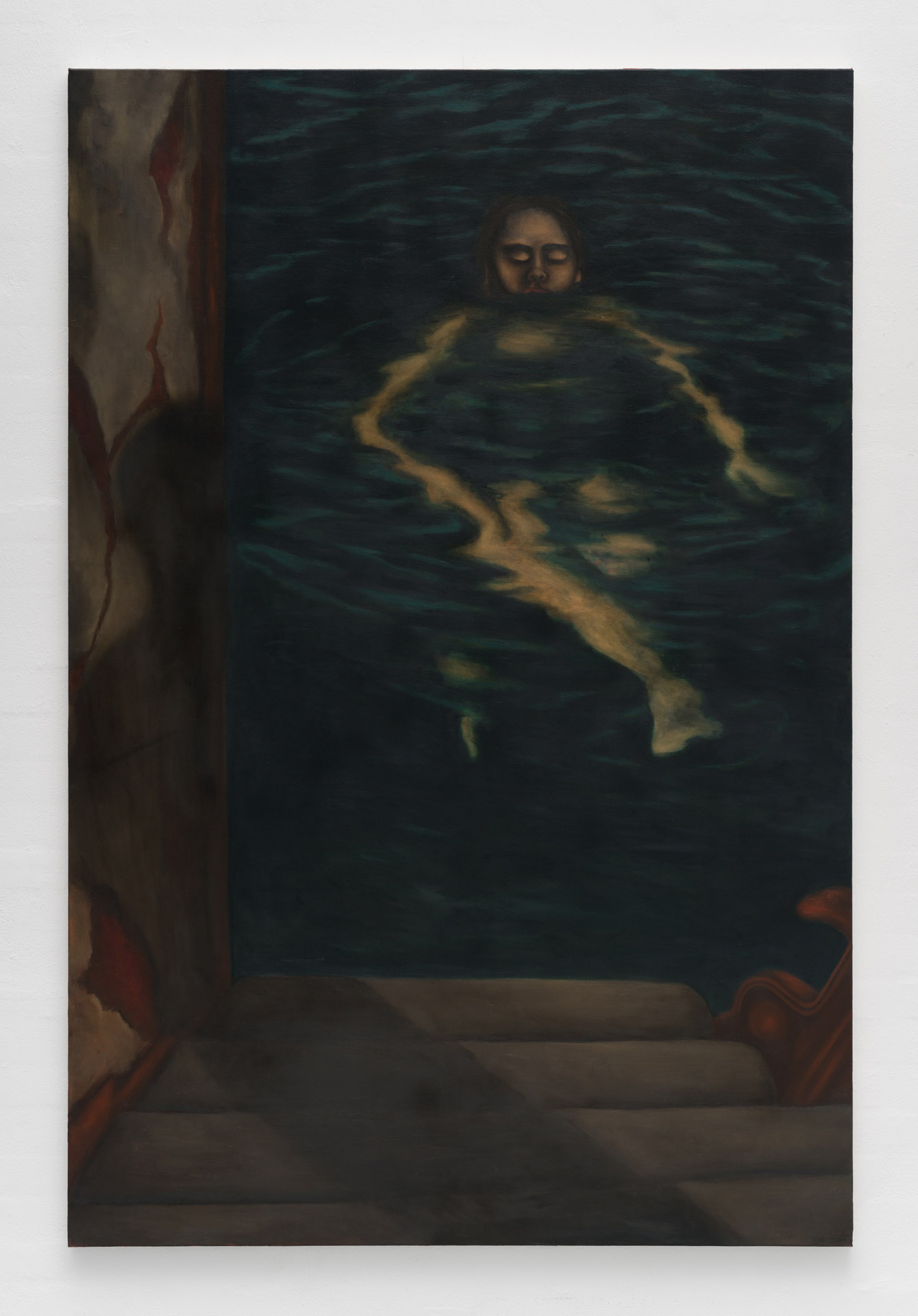

For example, Drowner (2020) presents a woman taking her final breath, her face just surfacing out of viscous, brown water. The painting seems to show her at a ruinous moment, too late for rescue, and yet she appears almost calm, resigned to her fate as the murky waters seem to actively split or part to allow her face to submerge. In another work, Descending (The Bather) (2021), an ungendered figure is seen – from aerial perspective – curled into a milky bath that is surrounded by swamp green tiles, the twisted end of a deep red shower curtain and a swash of blue fabric, a towel? The figure casts their gaze down over their own naked body, unaware of our presence as viewers but also somehow allowing us to look too. A feeling of deep solitude pervades as the protagonist descends (as in the title) into both the water and their melancholy mood.

A number of other works retain the same watery references but offer perhaps more political ideas. In Chimezie (rising and falling with the current) (2021), for example, a solitary man sits cross-legged on a squishy green sofa. His white t-shirt is unfeasibly creased – as is his brow – although he has a dazed, introspective expression that doesn’t so much reveal anxiety but preoccupation, his shoulders are relaxed and his head tilted ever-so-slightly to one side. Behind him on the hazy pink wall, a streak of dancing reflections, sunlight through dense foliage, animates the whole scene and provides the sense that nature here is in full force, dynamic and active in the face of human inaction and indecision. The title also suggests something of a surrender to the rising tides of global emergency.

In this work, as in others, Hammond deftly uses light, perspective and lines of sight not to provide illumination or clarification, but rather to create portentous uncertainty and a distortion of reality. In his work there is no empirical vantage point, as he says: ‘when painting I think about a surrounding physical and climatic sensibility – sources of heat, light or wind – their directionality and how they may affect the subject. Sometimes the figures seem to exist in a vacuum; neither hot nor cold, neither night nor day. That may be a proxy for a feeling of apathy or a condition the characters have been bludgeoned into.’ His use of an earth-red underpainting also contributes to the hostility that he enacts on his subjects: ‘it was initially employed as a traditional painting technique, a method to unify the image and use the red ground as a mid-tone. I began to enjoy the sort of hellish feel it gives the paintings; a sense of heat or nightmare/apocalyptic landscape.’ In this sense, Hammond’s characters seem to soak up the violence of their dystopian environments, mutating and metamorphosing quite literally though his distorted perspectives and manipulation of space, which evokes, once again, the surrealist question of dreams, as Hammond explains: ‘there is no fixed visual representation in our dreams or our mind’s eye. I hope my paintings are close to touching that idea in some way.’

While many of the recent paintings made for this exhibition refer to dreams or dreamscapes: Sell Me A Dream, (2020); Rorsch (Dream Sequence); Little Man (Dream Sequence) or Leopards (Dream Sequence) (all 2021), possibly the most oneiric is the titular While We Were Sleeping (2021). Here a gargoyle-like figure, deep claret in colour, his eyes aglow by the light of a full moon, exists as the backdrop to a presentation of a collection of sharp objects (knives, scissors, chisels, bradawls, needles) overlaid, almost categorically across the surface of the painting. The figure seems to be simultaneously confined by the range of tools as well as protected by them, as it ascends a dark stone staircase that reaches out of a turbulent sea. Interestingly (perhaps), gargoyles were originally designed in 13th century French architecture as the features on guttering that disposed of water, the term gargoyle coming from the French gargouille—the noise of water and air mixing in the throat (in English: gargle).

Which recalls, once again, the image of Drowner, her face about to be lost beneath the rippling water. Throughout his practice Hammond’s paintings embody the symbolic potentiality of surrealism and the contemporary anxieties that abound today. To these ends he renders reality and its strange and dangerous precarity as a series of disquieting yet dreamlike tableaux. His creation of analogies and allegories that speak to the global crises we face now are always smart, nuanced, empathetic and necessarily fierce.

‘…your hands come together to form their own peak

as the word meniscus arcs above the table

and crashes over the buzzing lunch-rush

room, the tiny bottles of cacao and ginseng washed

astray, counting for nothing, you are a single tear,

glued in the operating theatre. I am the serrated

dumb knife of I know, I know. the wave

breaks over its sutures. we look

elsewhere, at the backs

of our hands. our words step out raw

on the stage of ghost

fathers. we have both

been dreaming

of the toxic lake’[1]

[1] Daisy Lafarge, excerpt from Dredging the Baotou Lake in Life Without Air, London: Granta, 2020.