Artists: Keita Matsunaga, Kisho Kurokawa

Venue: Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles, US

Date: December 7, 2019 – January 25, 2020

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga

Nonaka-Hill is pleased to present new ceramic works by Keita Matsunaga in his first solo exhibition in the United States. The exhibition is on view through January 25th, 2020.

Born in 1986, Keita Matsunaga describes his generation as one which is concerned with all kinds of ideas of repair, renewal, remix and reuse. Citing major earthquakes and complex global concerns, the artist has incorporated this contemplation into the materials, processes and surface techniques of his sculptural ceramic practice. Another influence is architecture.

Matsunaga was raised by ceramic artist parents in Ichinokura, a town known for sake cup production in the ceramic industry region of Tajimi, Gifu. Ichinokura’s makers have long faces significant production and distribution obstacles; a limited supply of local clay forces reliance on clays brought in from elsewhere, and the town’s narrow streets prohibit passage of large trucks. The town’s production of sake cups and small ceramic wares can be understood as an adaption to these conditions.

Matsunaga left Ichinokura to study architecture, eventually finding work in the studio of the prominent architect, Sou Fujimoto, whom the artist cites as a major influence. According to Matsunaga, Fujimoto “asks the big questions” of the fundamental concepts of architecture. So, when Matsunaga realized that he was better suited for a life working in ceramics, he returned to Tajimi with an architect’s tendency to scrutinize the site conditions as a means to find inspiration for the project at hand. Of course, history informs architectural and ceramic decisions, as well.

The artist explains that the shape of a bowl evolves from the primal human action of scooping water with two hands to nourish oneself. The invention of the bowl allowed humans to share nourishment between people and must have had an immeasurable effect on the development of human communication. In Japan, the role of the tea-bowl in the high-art of tea-ceremony illustrates this point to an extreme. Matsunaga’s tea-bowls are covered with urushi (lacquer), which hasn’t been seen on ceramic bowls since the Jomon Era, from 9,000 to 3,000 years ago. Urushi was replaced by glaze, which is more efficient to produce, and urushi was relegated to a repair material for ceramics, used only as the crack-filler for kintsugi (gold leaf) repairs. Matsunaga finds significance in the use of a repair material as full surface coverage for his teabowls, while at the same time renewing a Jomon practice. Matsunaga has remarked that his urushi color choices recall the ornate and colorful Kunitani-ware (aesthetically opposite of Jomon) of Kanazawa area where he studied ceramics. Another personal association for Matsunaga’s bright colors may be a childhood-memories of swimming in rivers polluted by glazes dumped from ceramic factories, changing the river’s color day-by-day with unusual color combinations. The show’s largest work, from his “Void – surfaced with caution orange urushi that’s been muted black

Matsunaga finds equivalence between the physical act of making architectural models and of making ceramic sculpture; the object can be imagined in scales beyond itself. Similarly, Matsunaga’s shell-like “Void” works possess an undeniable exterior object-hood, so their title “Void” can only provoke contemplation of the object’s mysterious, perhaps infinite, inner-space. Some of these “Void” works utilize “ordered-in” clays from various sources, rolled into thin sheets and loosely layered. When fired, these different types of clay react in opposition to each other, creating fissures. Some of these works are fired in barley husks which

To display works which were made in Japan, the artist designed a multi-tiered metal scaffold, draped with digital photographs printed with intense color saturation onto vinyl rolls. The images bring the artist’s Japanese studio environment into the Los Angeles gallery; dappled light through a window, stains on a kiln plank, a rusted corrugated metal studio wall, and views of broken glazed ceramics by many contemporary makers accumulated into a landfill.

The works on view in the gallery’s central space were created during Matsunaga’s recent residency at Cal State University Long Beach’s Center for Contemporary Ceramics, invited by the program founder, artist Tony Marsh. To begin these works, Matsunaga mixed bits of broken, glazed ceramics from the CSULB studios’ waste-bins, studding the new, moist clay and formed sculptures. He applied photographic glaze decals with images from his Tajimi environs; his rusted metal studio wall and images of the Tajimi ceramicists’ community landfill of broken glazed ceramics. Upon firing, the B&W photographic images adhered to the forms’ surfaces and the chips’ glazes reactivated, bubbling up from within to appear like splatters on the surface. Photographic images of broken clay enveloping a form of unbroken clay invokes the reflexive surrealism of Rene Magritte, while another comparison can be made to the Japanese Mono-ha artist, Koji Enokura, whose painting objects picture repeated stains, transported via silkscreen process, conflating object and image to uncanny effect. At the same time, the artist has drawn two ceramics communities together on one object – thoughtfully combining the material of the form with the treatment of the surface.

Keita Matsunaga (b. 1986, Japan) works in Tajimi and Kani in Gifu Prefecture, Japan. He studied architecture at Meijo University, Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture and subsequently studied ceramics at Tajimi City Pottery Design, Tajimi and Technical Center and Kanazawa Utatsuyama Kogei Kobo, Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture. He has had numerous exhibitions in Japan including solo exhibitions at Tondo, Kyoto (2019); Pragmata, Tokyo (2016, 2019); Nihonbashi Mitsukoshi Main Store, Tokyo (2018); Utsuwa Note, Saitama (2016, 2018); Meguro Togeikan, Mie (2017); and group exhibitions at Paramita Museum, Mie (2019); SHOP Taka Ishii Gallery, Hong Kong (2019); Gallery Voice, Gifu (2016, 2018); Ichinokura Sakasuki Art Museum (2017); Nihonbashi Mitsukoshi Main Store, Tokyo (2016, 2017, 2018); Ginza Mitsukoshi, Tokyo (2015, 2016, 2017), Sokyo, Kyoto (2017); 21st Century Museum of Art, Kanazawa (2015); and Espace L’Une, Paris (2015). Matsunaga also has been selected for the 11th International Ceramic Exhibition, Mino, Gifu (2017); and he won the Encouragement Award at the 72nd Kanazawa Kogei Exhibition, Kanazawa (2016); selected for the 23rd Japan Ceramic Exhibition (2015), won the Encouragement Award at the International Itami Craft Exhibition, Hyogo (2014), and won Grand Prize at the Takaoka Contemporary Craft Competition, Toyama (2013). His work is in the permanent collection of The Museum of Ceramic Art, Hyogo.

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Keita Matsunaga, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

A show about an architectural monograph: The Work of Kisho Kurokawa, Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose

A show about an architectural monograph:

The Work of Kisho Kurokawa

subtitled: Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose

published by: Bijutsu Shuppan- Sha, LTD

in the year: 1970

designed by: Kiyoshi Awazu

with photographs by: Tomio Ohashi

and several other photographers and contributors *

including a poster by: Kiyoshi Awazu

and a musical score on vinyl: Music for Living Space

composed by: Toshi Ichiyanagi

with the architectural manifesto: Capsule Declaration

by: Kisho Kurokawa

recited by: a computer- generated voice

combined with: Gregorian chants and other sounds

with cooperation of: Kyoto University, Department of Electronics

and published by: Music Project, Inc.

in the year: 1969

originally played in: the inner Future Section

of The Tower of the Sun

by Taro Okamoto

from: 1969/70

which punctuated: the Space Frame / Big Roof structure

designed by: Kenzo Tange with Koji Kamiya and Asao Fukuda

of the: Festival Plaza

designed by: Atsushi Ueda and Arata Isozaki

in the: Symbol Zone

of: Expo ’70, Osaka

master- planned by: Kenzo Tange and Uzo Nishiyama

embracing the theme: Progress and Harmony for Mankind

&

a visionary building in peril: Nakagin Capsule Tower, Tokyo

designed by: Kisho Kurokawa

and built: 1970/1972

* Photographers:

Masao Arai, Tomio Ohashi, Shigeo Okamoto, Takashi Koyama, Yu Suzuki, Eitaro Torihata,Non Shashinshitsu, Yukio Futagawa, Hideki Hongo Osamu Murai, Yoshio Watanabe, Daiho Yoshida, Kikutake Kiyonori Architects planning office, GK Industrial Design Office, Maki and Associates, Matsui Gengo Laboratory, Takenaka corporation, Interior, Shotenkenchiku- sha, Shokokusha, Shinkenchiku- sha Co., Ltd.

* Reference material:

Homo movens – Chūōkōronshinsho,Kodokenchikuron Kenchikubunka – Shokokusha,Toshi design – Kinokuniya shinsho, Kindai Kenchiuku –

Kindaikenchikusha, a + a – Foundation of Light metal association, Kikan geijutsu – Kikan geijutsu shuppan,Mainichi graph – Mainichi shinbunsha, Chūōkōron, Shukanbunshun, The Asahi Shimbun, The Sankei Shimbun, The Chunichi Shimbun, The Hokkaido Shi mbun, The Mainichi Shimbun, The Yomiuri Shimbun

* Editing composition staff:

Kiyoshi Awazu, Yasuko Nishigaki, Hidemi Koyama, Ikuyoshi Shibukawa, Yusuke Tamura, Toshiko Isa

The exhibition will be held from December 7, 2019 – January 25, 2020.

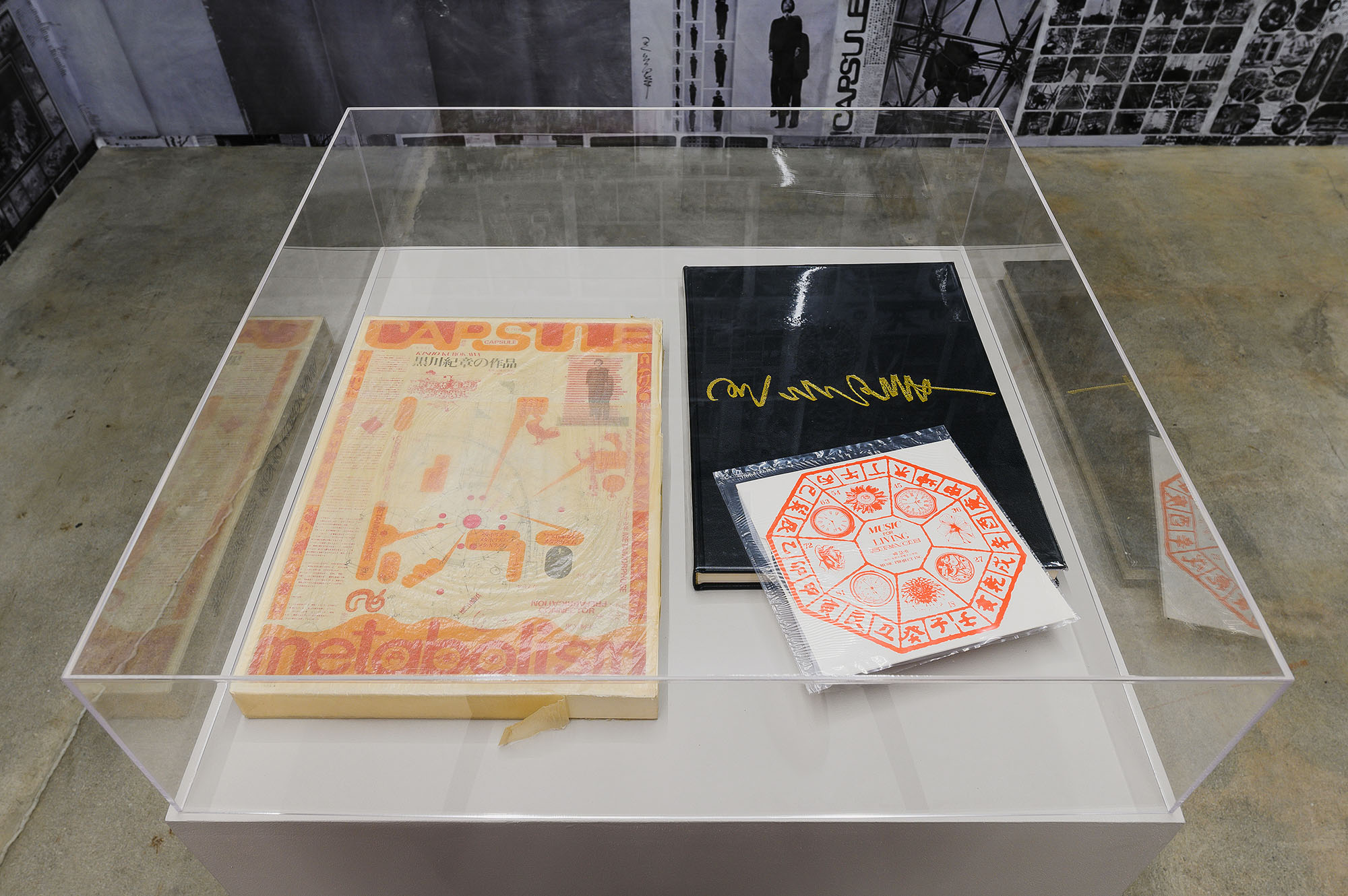

For this exhibition, focused on 50 year old book, the gallery has photographed each page of the book individually, printed the images at a copy shop, and wheat-pasted them sequentially to cover the gallery walls. The poster inserts from two copies of the book are on display, allowing viewers to see both sides of the double-sided poster insert. And, the book’s vinyl record insert is being played. Effectively, visitors can absorb the rare book’s contents, which still look and sound “futuristic”.

In the gallery’s larger space, a concurrent solo exhibition by Keita Matsunaga is on view. Matsunaga was trained as an architect but left that vocation for a career in ceramic sculpture. The artist has moved from the geometric and rigid forms of architecture to the organic and malleable potential of ceramic. The Metabolist architects sought, through their works and theories, a malleability in architectural programs, creating buildings which are preprogrammed for inevitable change. “The Work of Kisho Kurokawa” was published in 1970 while the architects of the Metabolist movement were being seen by the Expo 70 Osaka attendees, so the book exists as a report on the movement’s current state of affairs. The promise and potential of Metabolist Architecture is conveyed in accordance with global artistic “Intermedia” trends of the moment, the between architect, graphic designer, musician and a long list of collaborators (thus the exhibition’s long “credit roll” title).

Nonaka-Hill hopes that this exhibition of “big idea” architecture conceived by Kurokawa and his peers in Japan’s post war period will be compared and contrasted with some ideas that are currently in discussion in the United States, namely “Green New Deal”. We also seek to draw awareness to the current situation with Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower, from 1972. This building, a Masterpiece in disrepair, is located near Tokyo’s Ginza business district, and is thus vulnerable to the vicissitudes of high value real estate development. Efforts to preserve this building are underway, and we seek to draw attention to this iconic structure, hopefully securing its future through increased global interest.

The Work of Kisho Kurokawa: Capsule, Spaceframe, Metabolism, Metamorphose published in 1970 by Bijutsu Shuppan-sha is an anthology of Kisho Kurokawa’s architectural concepts and designs. As one of the founders of the Metabolism movement of the 1960s, Kurokawa believed that cities should be developed based on organic paradigms and professed that prefabricated modular systems as ideal modes of building that can readily adapt to the fast pace of modern living. The large-scale book, designed by Kiyoshi Awazu, was packaged with an Awazu-designed poster and a 7-inch vinyl record, Music for Living Space (1969) composed by Toshi Ichiyanagi. Published in the same year as the Osaka Expo ’70 the book is organized by theme––“Capsule,” “Prefabrication,” “Spaceframe,” “Helix,” “Bunkai” [分解division/deconstruction)], “Seichō no fushi” [成長の節(growth node)], “Connector,” “Michi no kenchiku” [道の建築 (street architecture)], “Metamorphose,” and “Jusō no kōzo” [重層の構造 (multistoried construction)]–– that define his philosophy of architecture and urban planning, and features architecture designed by Kurokawa through 1970, which include the Takara Beautillion Pavilion and Capsule House in Theme Plaza for Expo ’70 and Seattle Art Museum, interspersed with renderings and models for urban planning and architecture such as the Helix City (1961), Floating Factory Metabonate (1969).

Awazu’s graphics, a montage of eclectic images, expressive typography, and dynamic layout, enlivens Kurokawa’s vision on the future of Japanese architecture and its symbiotic relationship with daily life. Awazu, was an integral figure of the Metabolism movement from its inception. He was a creator of Metabolism’s logo and responsible for the book design of Metabolism 1960 (1960) by Noboru Kawazoe the architecture critic and co-founder of the Metabolism movement. A master practitioner of capturing audience intrigue and imagination in print form, Awazu’s imagery complements the architect’s written message with his unique visual syntax. To that effect, the immediacy of the images makes Kurokawa’s concepts more approachable to a wider audience.

Music for Living Space by Toshi Ichiyanagi, originally played inside the Tower of the Sun by Taro Okamoto at Expo ’70 comprises of Gregorian chants integrated with a computer-generated voice reciting Kurokawa’s Capsule Declaration. Spending much of the 1950s and 60s in the United States, Ichiyanagi had studied with John Cage and was active in the Fluxus movement, frequently at the cutting edge of intermedia projects. The technology to create human speech from a computer was at its early stages at the time and demonstrated the new possibilities of the medium proving to the world the rapid technological advancements made in the host nation after World War II. Inserted inside the book, Music for Living Space as a vinyl record could readily be played at a common domestic setting in 1970. The Gregorian chant layered with the robotic voice, ending with sound of heartbeats, implicate an otherworldly experience that converge the spiritual, the body, and the computer while promulgating Kurokawa’s manifesto. Put simply, the Gregorian chants, the heartbeat and the computer voice could also represent past, present and future.

Kisho Kurokawa (1934-2007) was born in Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture. He studied architecture at Kyoto University obtaining a bachelor’s degree in 1957, received his master’s degree in architecture in 1959 and a doctorate’s degree in architecture in 1964, both from Tokyo University. Kurokawa practiced architecture under Kenzo Tange’s mentorship in Tange Lab at Tokyo University in the late 1950s. In 1960, he co-founded the Metabolist Movement. Kurokawa founded his own firm, Kisho Kurokawa Architects & Associates in 1962. Kurokawa architectural work in Japan include Expo ’70 Pavilions –– Takara Beautillion Pavilion, Capsule House in Theme Plaza, and Toshiba Ihi Pavilion, Osaka (1970); Nakagin Capsule Tower, Tokyo (1970); Sony Tower, Osaka (1975); National Museum of Ethnology, Tokyo (1977); National Bunraku Theatre, Osaka (1983); Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art (1988); and Toyota City Stadium, Aichi (2001). Outside Japan, Kurokawa designed the Van Gogh Museum Amsterdam (1998); Pacific Tower, Paris (1992); Republic Plaza, Singapore (1995); and Kuala Lumpur International Airport, Malaysia (1998). Some of the books Kurokawa has written are Purehabu jutaku [プレハブ住宅 (prefabricated living) ] (1960), Toshi dezain [都市デザイン (city design)] (1965), Homo mōbensu [ホモ・モーベンス (homo movens)](1969), Kenchiku ron I,II [建築論I・II (architectural theory I, II)] (1970/1990), Nomado no jidai [ノマドの時代(era of the nomad)](1989), Kenchiku no uta [ 建築の詩(architectural poetry)] (1993), Kyōsei no shisō [共生の思想(thoughts on shared living)](1991).Exhibitions dedicated to the architect were held at esteemed institutions including, The Art Institute Chicago (1998); Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (1999); Centre Pompidou, Paris (1997); The National Art Center, Tokyo (2007); and Nagoya City Art Museum (2001). His works are in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Centre Pompidou, Paris; and The Art Institute Chicago. Kurokawa is a recipient of a multitude of awards including, International Architecture Award 2006 for the National Art Center, Tokyo (The Chicago Athenaeum, 2006); 10th Public Building Award Prize, for Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum (2006); Walpole Medales of Excellence (2005); and International “CITIES Award for Excellence”(2002).

Kiyoshi Awazu (1929-2009) was born in Tokyo. He was an acclaimed self-taught graphic designer who contributed countless posters for cinema, exhibitions, and theater. Seeing beyond the boundaries that separated the arts, Awazu also practiced exhibition design and made experimental films. He was also an advocate for social issues. Winning the grand prize at the Nissenbi (Japan Advertising Artists’ Club) Exhibition for his poster, Umi wo kaese [海を返せ(give back our sea)] in 1955 became the impetus for Awazu seriously pursuing his practice in graphic design. He started his own design firm in 1964. Awazu organized Expose 1968, an art symposium that took place at the Sogetsu Art Center, where both Ichiyanagi and Kurokawa participated. In 1970, he was charged with the artistic direction of the Theme Plaza at Expo ’70. Across multiple years, Awazu was a frequent participant at the International Design Conference in Aspen as panelist, jury and exhibiting artist. He has won multiple awards including sekai firumu posutā contesuto [世界フィルムポスターコンテスト(world film poster contest) in 1958, won special prize at the International Poster Biennale in Warsaw in 1970 and 1982, and won grand prize at the Sekai de mottomo utsukushii hon no tenrankai [世界で最も美しい本の展覧会 (the world’s most beautiful books exhibition)] in 1974. Exhibitions featuring Awazu have been held at Walker Art Center, Minneapolis (1986); Kawasaki City Museum, Kanagawa (1988); Museum of Modern Art, New York(1989, 2012); Japanese American Cultural and Community Center, Los Angeles (1992); Printing Museum, Tokyo (2000, 2002, 2006); Los Angeles County Museum of Art (2017); and 21st Century Museum of Art Kanazawa, Ishikawa (2007, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 ). His works are in permanent collections of 21st Century Museum of Art Kanazawa, Ishikawa; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Toshi Ichiyanagi (1933) was born in Kobe. He studied composition under Kishio Hirao, Tomojiro Ikenouchi, and John Cage and studied piano under Chieko Hara and Beveridge Webster. Ichiyanagi attended Julliard School of Music in New York from 1954 to 1957. Invited by the Festival of Institute of Twentieth Century Music he returned to Japan in 1961. In 1966, Ichiyanagi received a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, and returned to the U. S. conducting recitals of his works all over the country. In 1976, he was composer-in-residence at Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst (DAAD) in Berlin, where he resided for six months. Ichiyanagi has toured and presented his work extensively throughout Europe, Japan, and the United States. He has received commissions from the Pro Musica Nova Festival, Bremen, Germany (1976); Metamusik Festival, Berlin, Germany (1978); Cologne Festival of Contemporary Music, Cologne, Germany (1978, 1981); Holland Festival, Amsterdam, Netherlands (1979); and the Berliner Festspiele, Berlin, Germany (1981). He has presented and premiered his work at Carnegie Hall, New York; Seibu Theatre, Tokyo; and the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Paris. In the 1980s and 1990s Ichiyanagi presented a numer of large-scale works commissioned by the National Theatre of Japan. In 1989, he premiered Reigaku Symphony No.2 “Jitsugetsu Byobu Isso ― Kokai,” using two halls of the National Theatre simultaneously. In 1989 Ichiyanagi formed the Tokyo International Music Ensemble―The New Tradition (TIME), an orchestral group focused on traditional instruments and shomyo, a style of Japanese Buddhist chant. TIME has toured across the United States and Europe. Ichiyanagi is the recipient of countless awards and honors, including the Elizabeth A. Coolidge Prize (1955), Serge Koussevitzky Prize (1956), and Alexander Gretchaninov Prize (1957) from the Juilliard School; first place in the Mainichi Music Competition (1949, 1951); Grand Prix of the Nakajima Prize (1984); L’ordre des Arts et des Lettres of the French Republic (1985); Mainichi Newspaper Art Prize (1989); Kyoto Music Grand Prize (1989); Suntory Music Prize (2002); and the Japan Art Academy Prize and Imperial Prize from the Japan Art Academy (2017). He was awarded a Medal with Purple Ribbon (1999) and Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette (2005) from the Japanese Government and has been recognized as a Person of Cultural Merit since 2008. He has received five Otaka Prizes for Symphony No.10 (2016), Symphony “Berlin Renshi” (1990), Piano Concerto No.2 “Winter Portrait” (1989), Violin Concerto “Circulating Scenery” (1984), and Piano Concerto No. 1 “Reminiscence of Spaces.” (1981).

English translation of excerpts from:

Kisho Kurokawa’s “Capsule Declaration”, 1969

first published in SD magazine’s March issue, 1969

and recited by a computer-generated voice in:

Toshi Ichiyanagi‘s “Music for Living Space”,

composed in 1969 and played within the

Also, this music was published as a 7” vinyl insert in “The Work of Kisho Kurokawa: Capsule, Spaceframe, Metabolism, Metamorphose”, published in 1970 by Bijutsu Shuppan-sha, Tokyo.

Capsule Declaration

Article 1

The capsule is cyborg architecture. Man, machine and space build a new organic body which transcends confrontation. As a human being equipped with a man-made internal organ becomes a new species which is neither machine nor human, so the capsule transcends man and equipment. Architecture from now on will increasingly take on the character of equipment. This new elaborate device is not a ‘facility’, like a tool, but is a part to be integrated into a life pattern and has, in itself, an objective existence.

Article 2

A capsule is a dwelling of Homo movens. The rate at which city dwellers move home in the United States is around 25 per cent a year. Soon the rate in Japan will exceed 20 per cent a year. Urban size can no longer be measured in terms of night-time (residential) population. The night-time population taken together with day-time population, or the pattern of movement of the population throughout the day, will become the index of the features of city life. People will gradually lose their desire for property such as land and big houses and will begin to value having the opportunity and the means for free movement. The capsule means emancipation of a building from land and signals the advent of an age of moving architecture.

Article 3

The capsule suggests a diversified society. We strive for a society where maximum freedom for individuals is sanctioned and where there is a wide range of options. In an age when organizations and society determined the city space, the infrastructure formed the physical environment of the city. In contrast, the capsule expresses the individuality of an individual–his challenge to an organization and his revolt against unification.

Article 4

The capsule is intended to institute an entirely new family system centered on individuals. The housing unit based on a married couple will disintegrate, and the family relationships between a couple, parents and children will be expressed in terms of the state of docking of many capsules of individuals’ spaces.

Article 5

The true home for capsule dwellers, where they feel they belong and where they satisfy their inner, spiritual requirements, will be the metapolis. If the result of docking of capsules is called a household, then docking capsules and communal space forms social space. The plaza as a religious space, symbol of authority or setting for commercial transactions disintegrates, and the public space with which individuals identify themselves will make the metapolis the new quasi-domestic haven. A self-sufficient community where the daily round is completed within a closed circle will perish. A haven will become a spiritual domain transcending concrete everyday space.

Article 6

The capsule is a feedback mechanism in an information-oriented, a ‘technetronic’, society. It is a device which permits us to reject undesired information. Our society is emerging form the industrial age and entering a technetronic age. The industrial pattern based on the manufacturing industries is changing into one based on information industries, such as the knowledge industry, education industry, research industry, publishing industry, advertising industry and leisure industry. To protect us from the flood of information and the one-way traffic in information, we should have a feedback mechanism and a mechanism which rejects unnecessary information. The capsule serves as such space.

Source: Kisho Kurokawa, Metabolism in Architecture, (London: Studio Vista), 75-85.

A show about an architectural monograph: The Work of Kisho Kurokawa, Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

A show about an architectural monograph: The Work of Kisho Kurokawa, Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

A show about an architectural monograph: The Work of Kisho Kurokawa, Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

A show about an architectural monograph: The Work of Kisho Kurokawa, Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

A show about an architectural monograph: The Work of Kisho Kurokawa, Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

A show about an architectural monograph: The Work of Kisho Kurokawa, Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

A show about an architectural monograph: The Work of Kisho Kurokawa, Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

A show about an architectural monograph: The Work of Kisho Kurokawa, Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

A show about an architectural monograph: The Work of Kisho Kurokawa, Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

A show about an architectural monograph: The Work of Kisho Kurokawa, Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

A show about an architectural monograph: The Work of Kisho Kurokawa, Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

A show about an architectural monograph: The Work of Kisho Kurokawa, Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

A show about an architectural monograph: The Work of Kisho Kurokawa, Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

A show about an architectural monograph: The Work of Kisho Kurokawa, Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

A show about an architectural monograph: The Work of Kisho Kurokawa, Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

A show about an architectural monograph: The Work of Kisho Kurokawa, Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose, 2019-2020, exhibition view, Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles