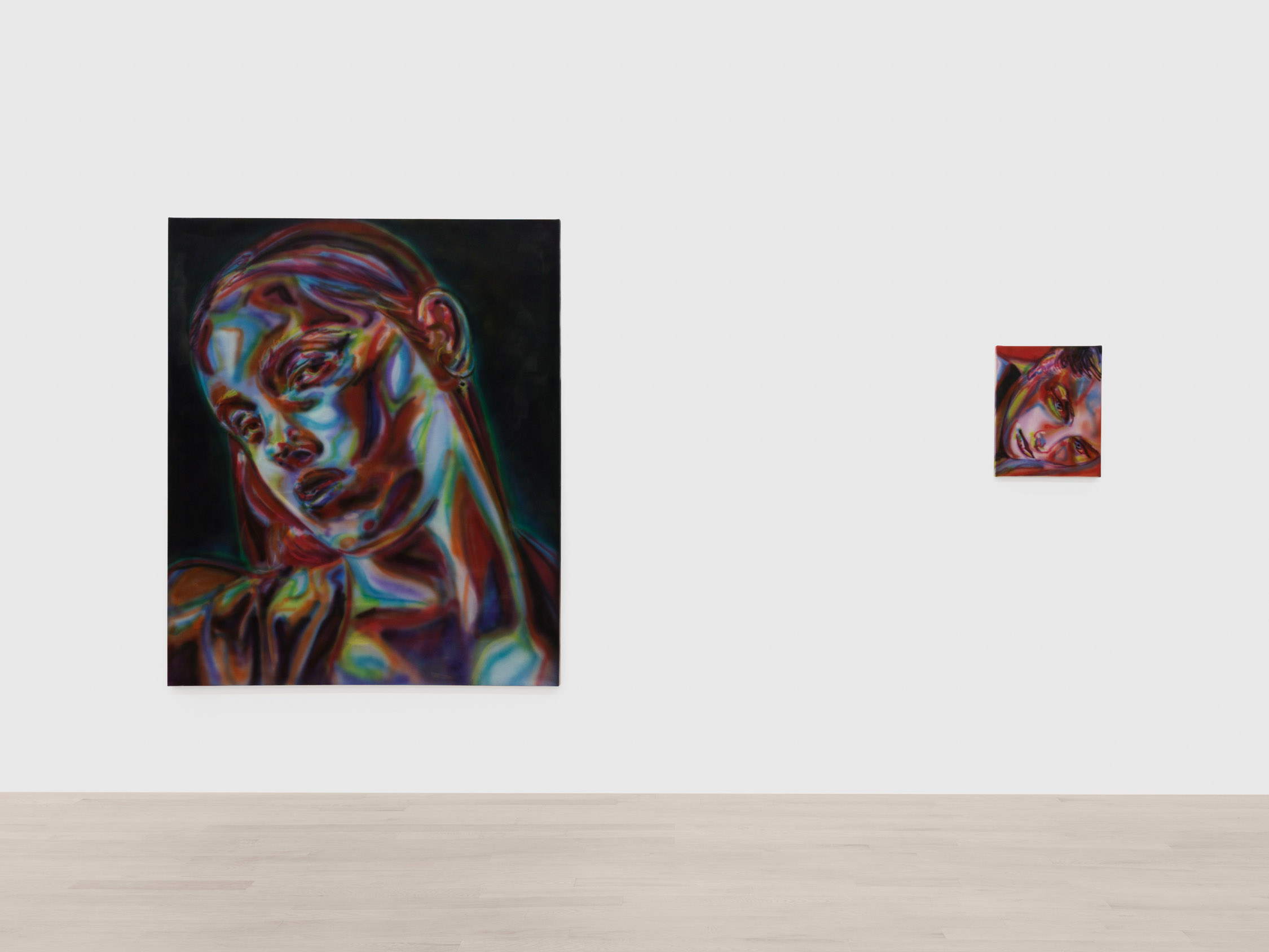

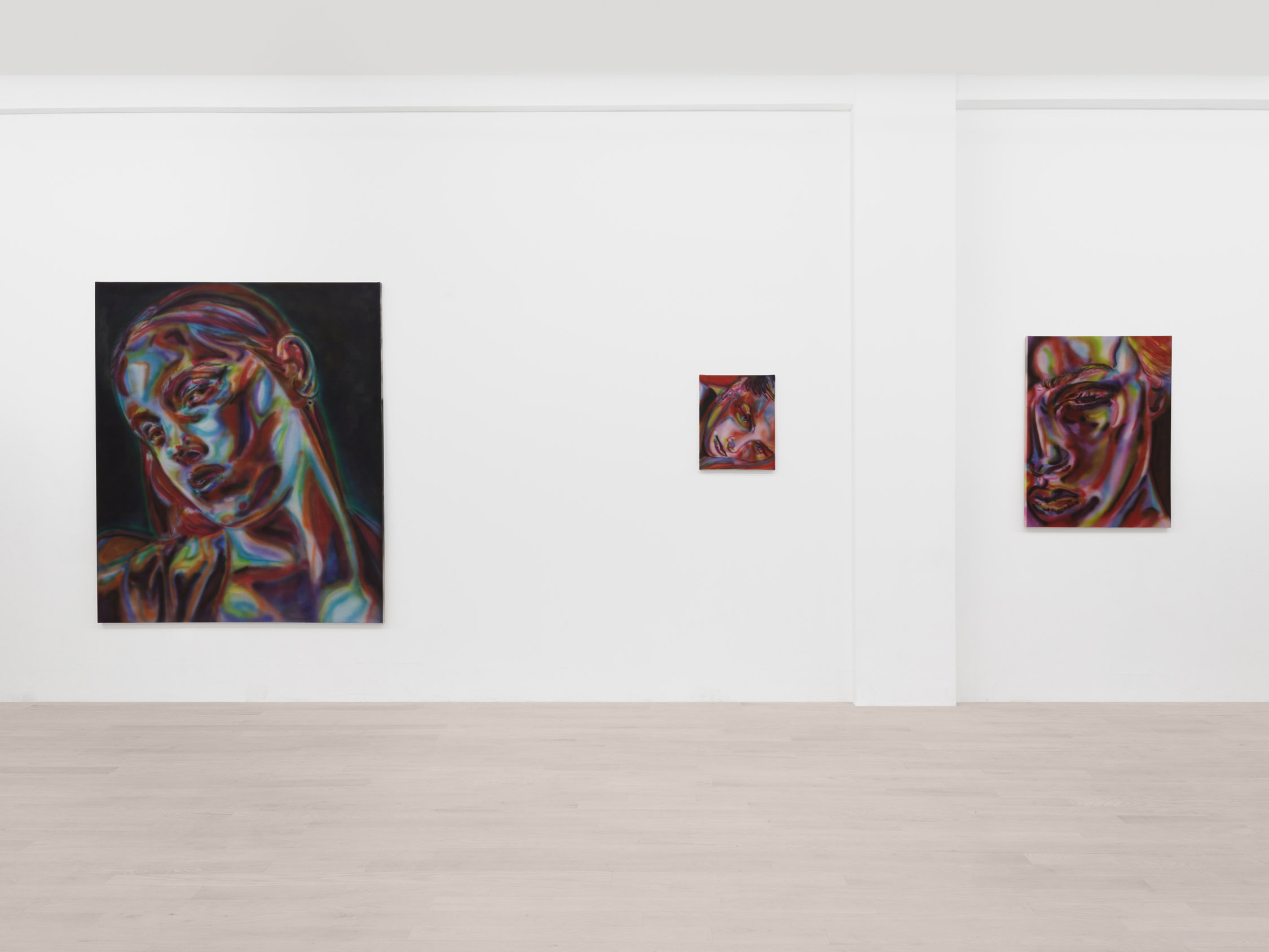

Artist: Katie Hector

Exhibition title: Ego Rip

Venue: Management, New York, US

Date: April 12 – May 12, 2024

Photography: ©installshots.art / all images courtesy of the artist and Management, New York

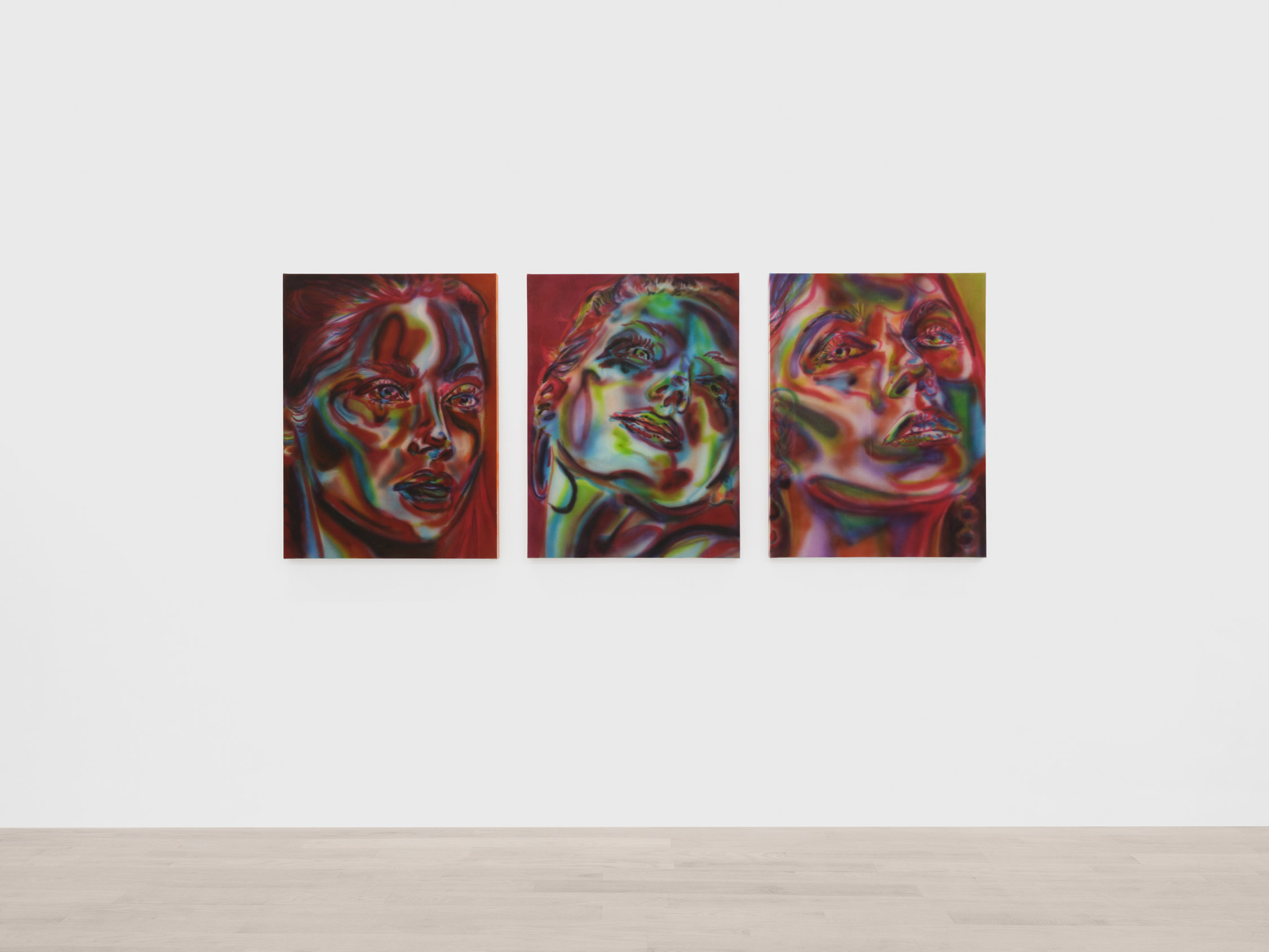

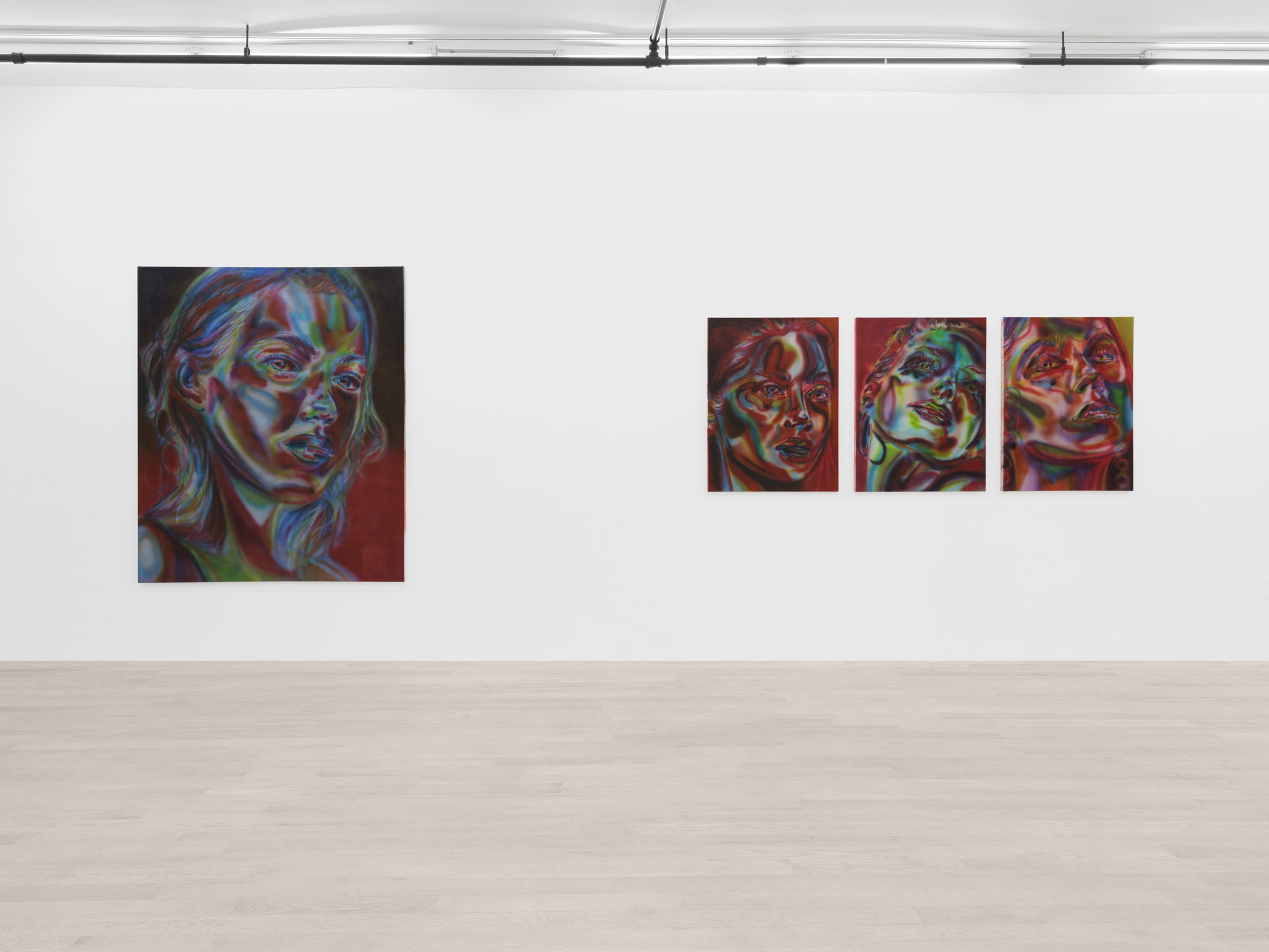

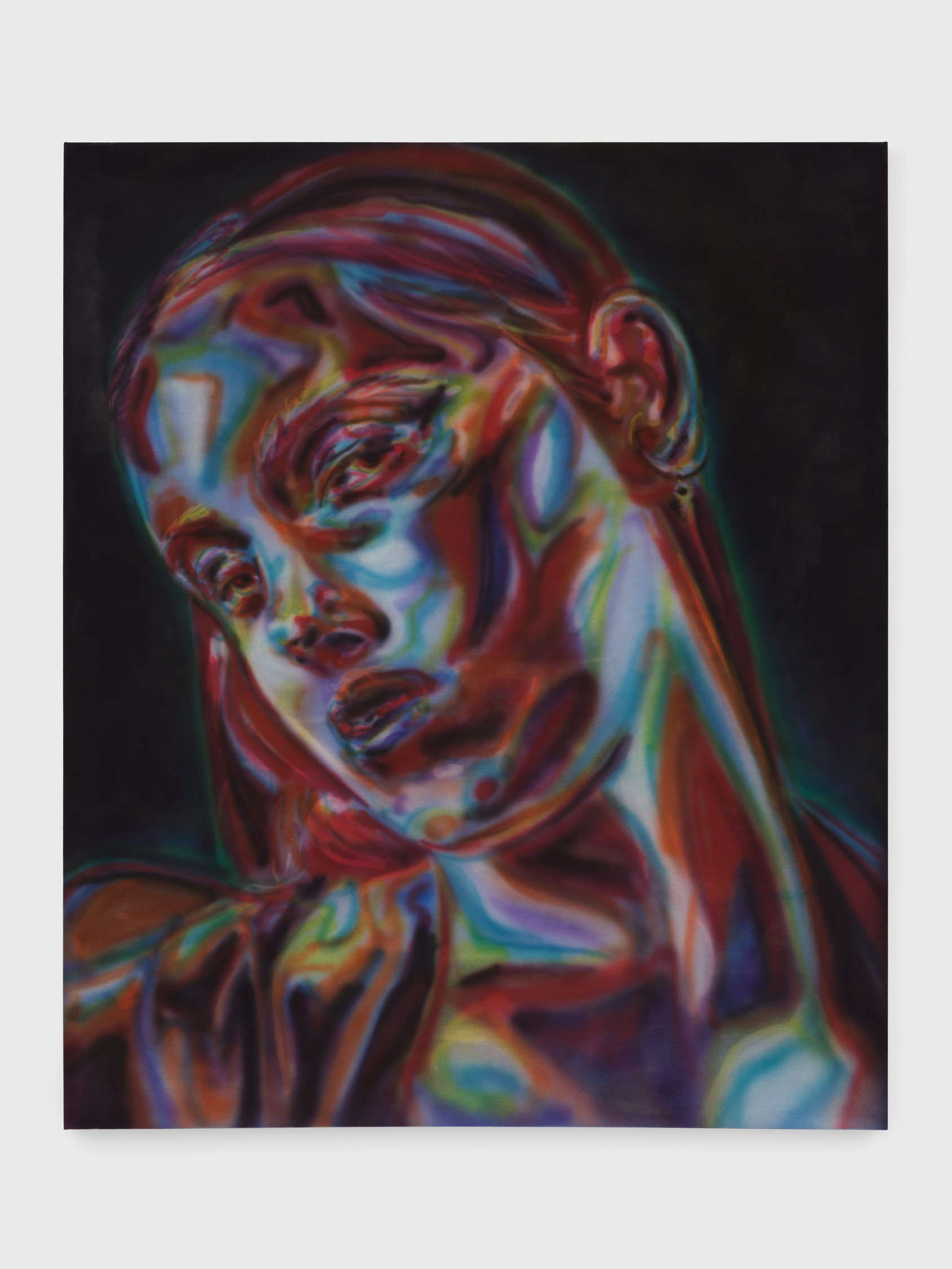

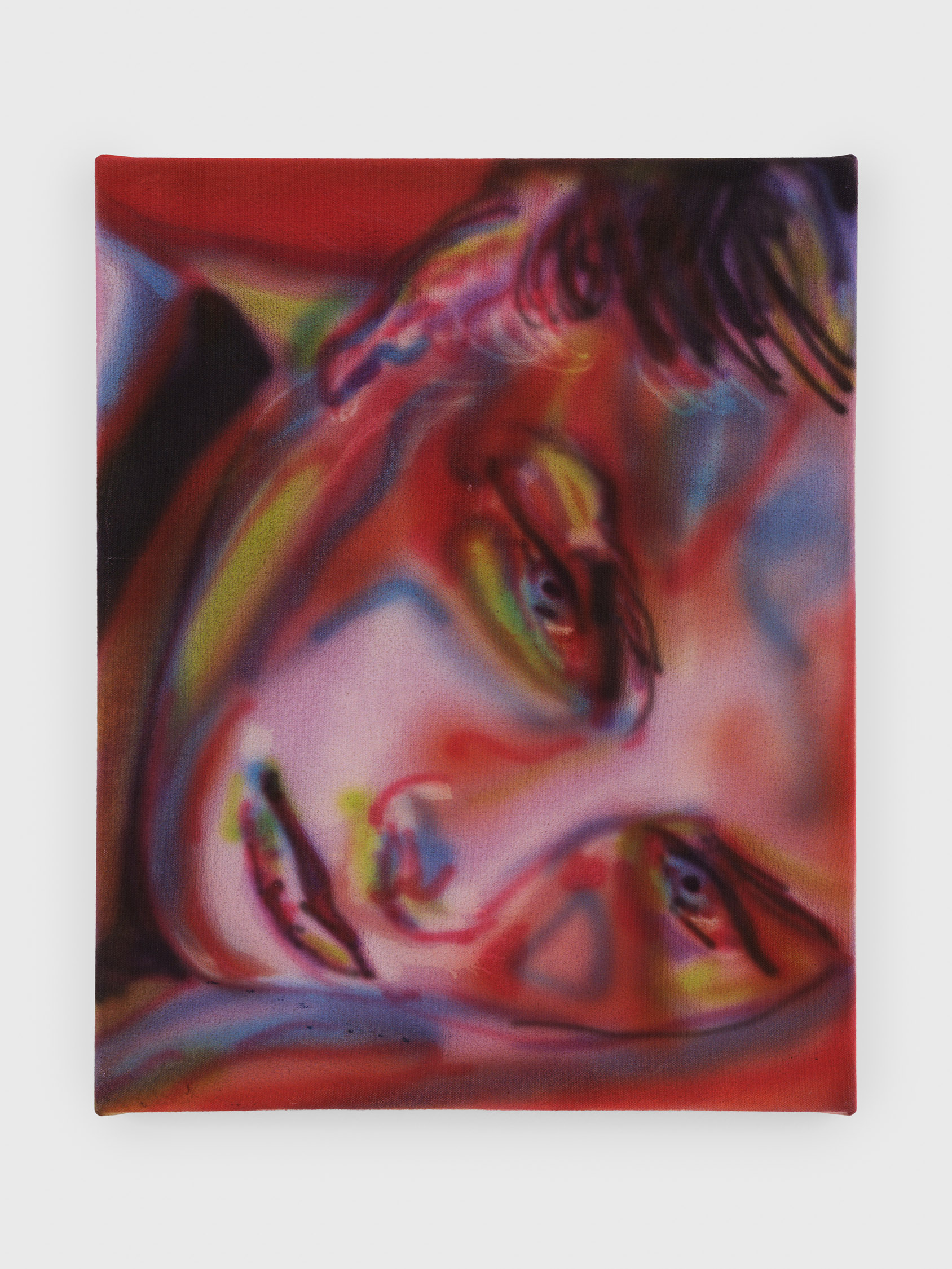

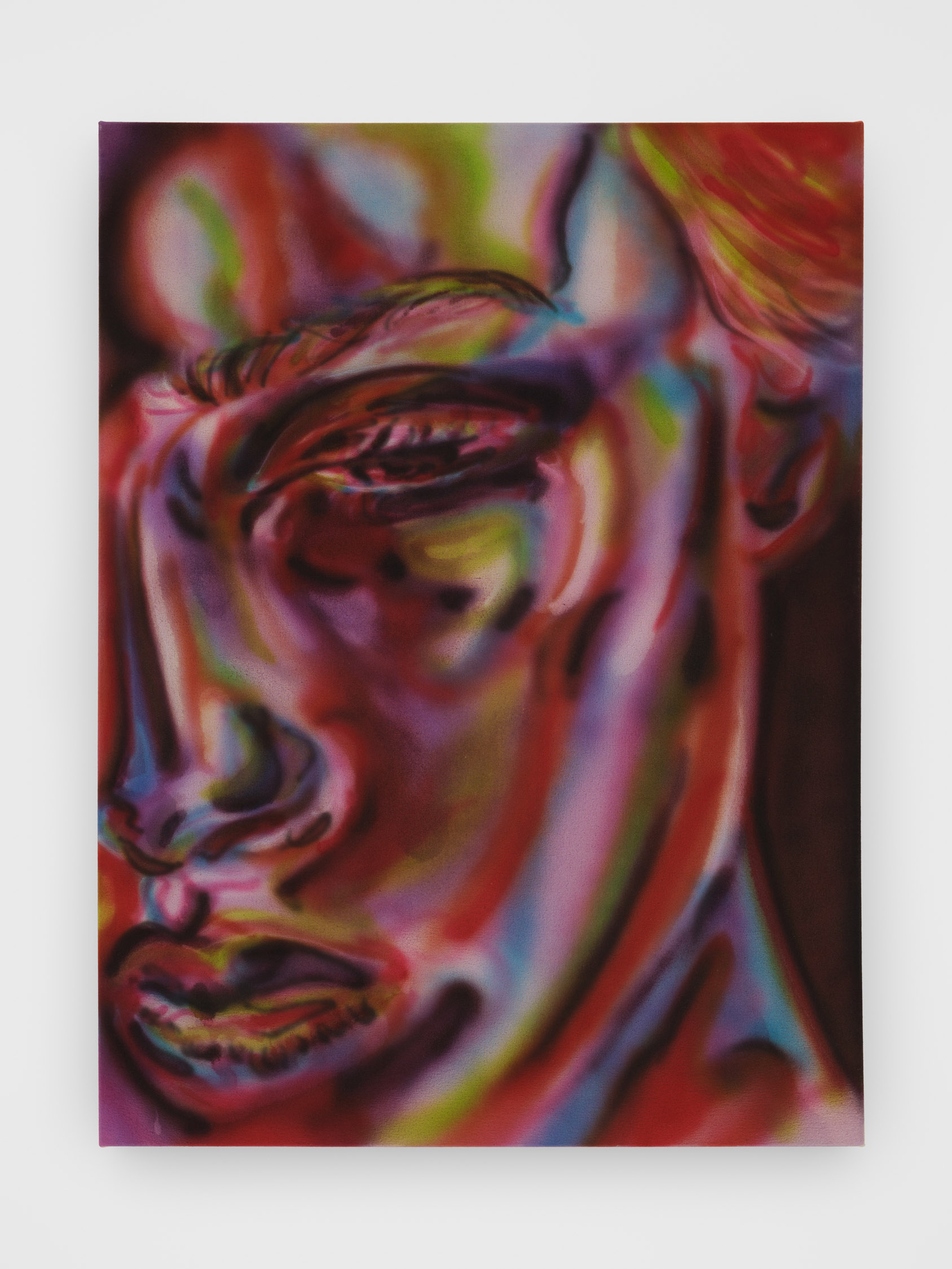

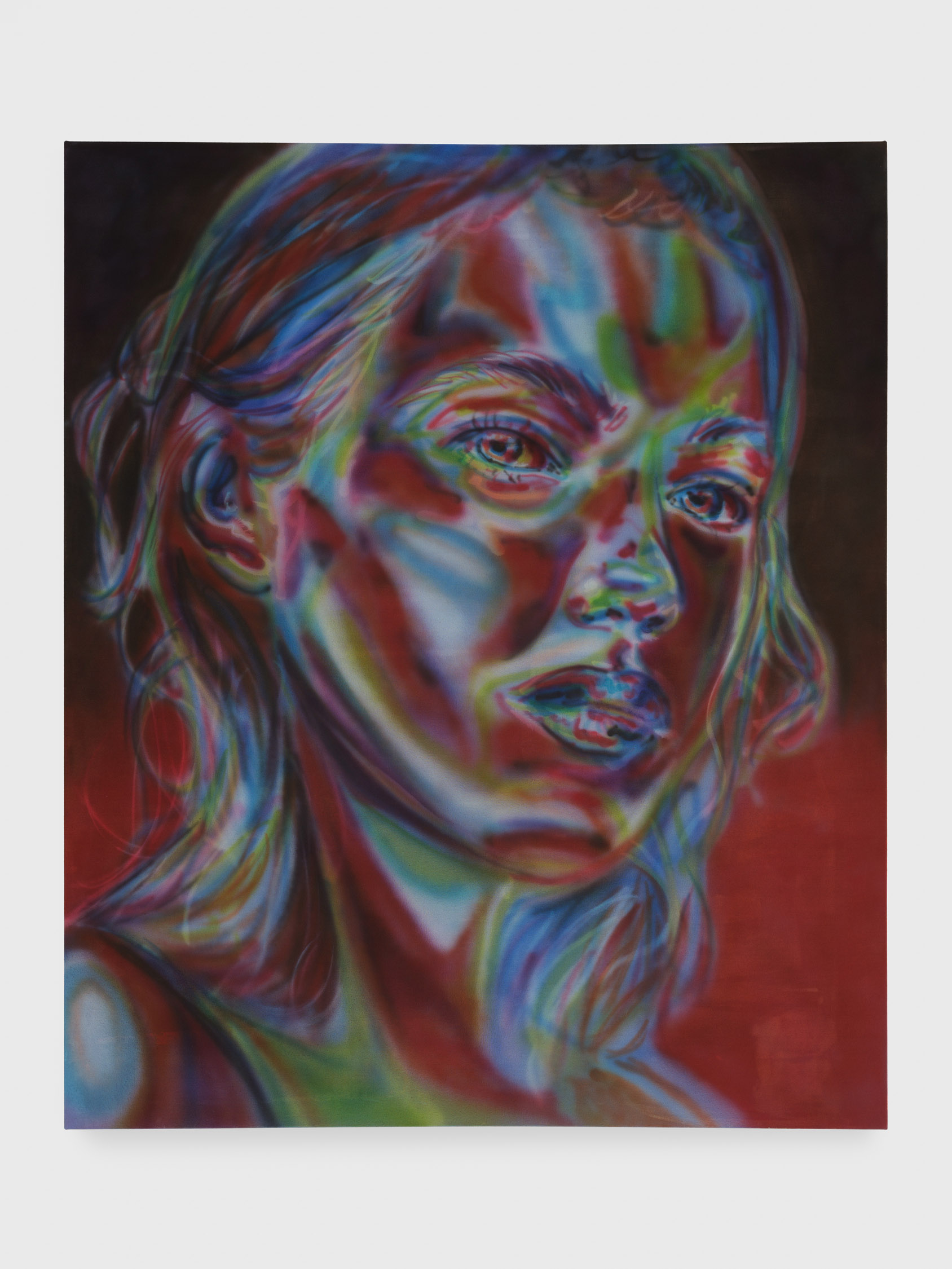

Los Angeles-based artist Katie Hector paints without paint, utilizing bleach and dye applied directly to the substrate, in obsessive layers and a successive play of absence and presence. In the exhibition Ego Rip, the artist focuses on contemporary portraiture, manifesting rather than mirroring the relationship between the erasure and stain of selfhood in our dissociative social reality. Explicitly memorial and composed at the site of a loss, the works in Ego Rip present portraiture as lack rather than plentitude and individuals as symbols rather than subjects—luminous, even metallic, ciphers, according to Hector, of “loss, grief, intimacy, and longing.” At its heart is a death, a grieving, a prayer.

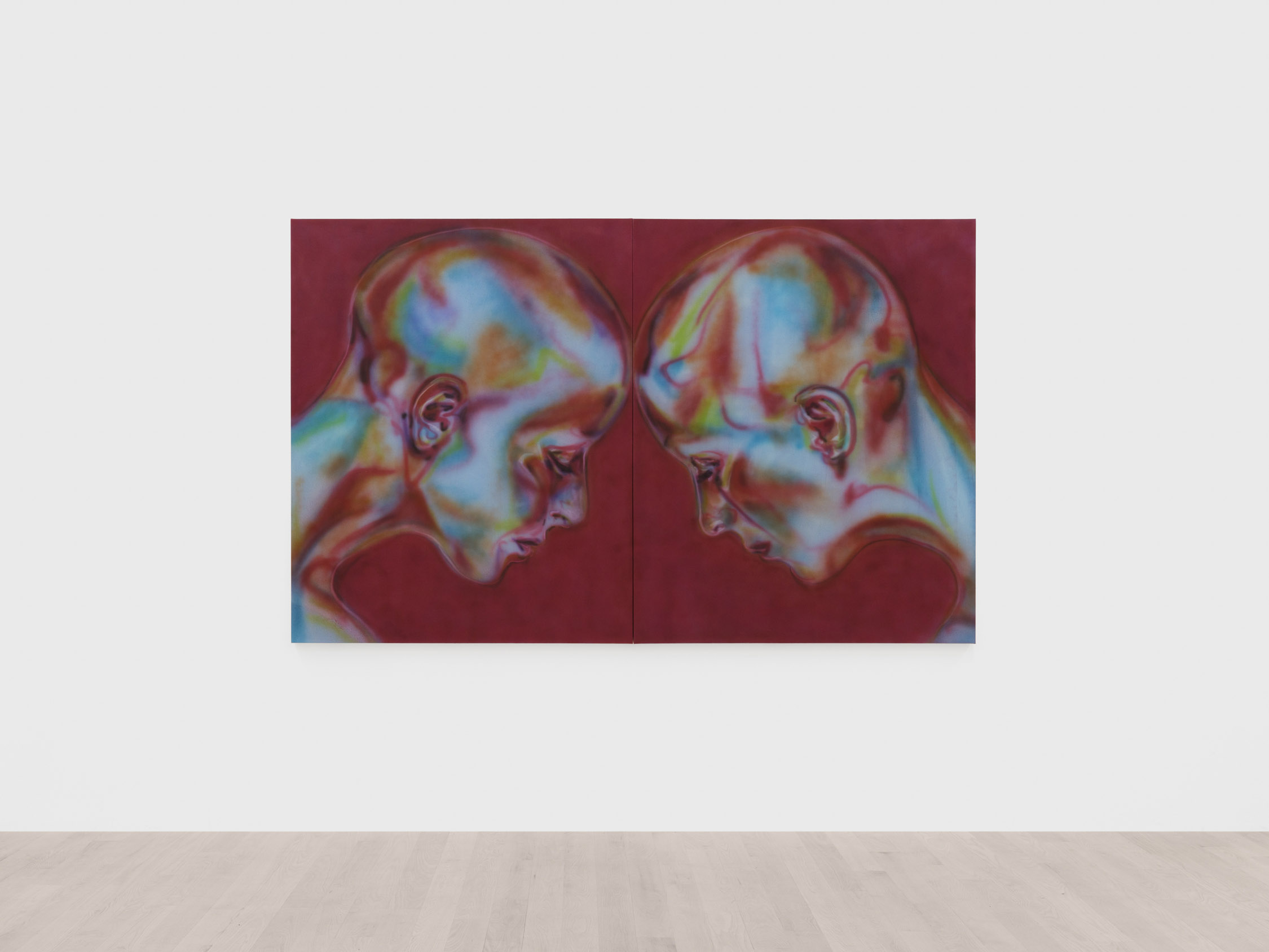

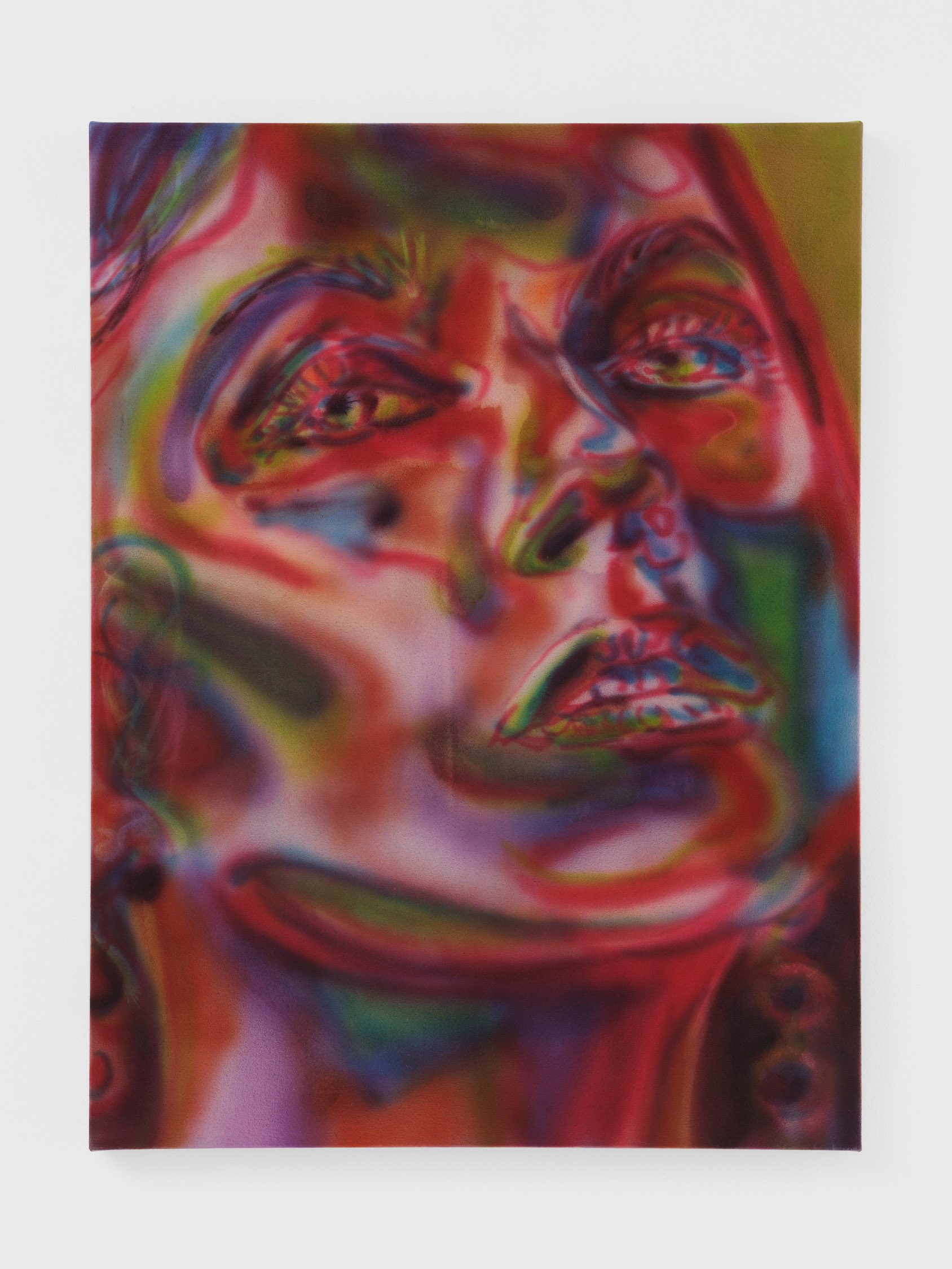

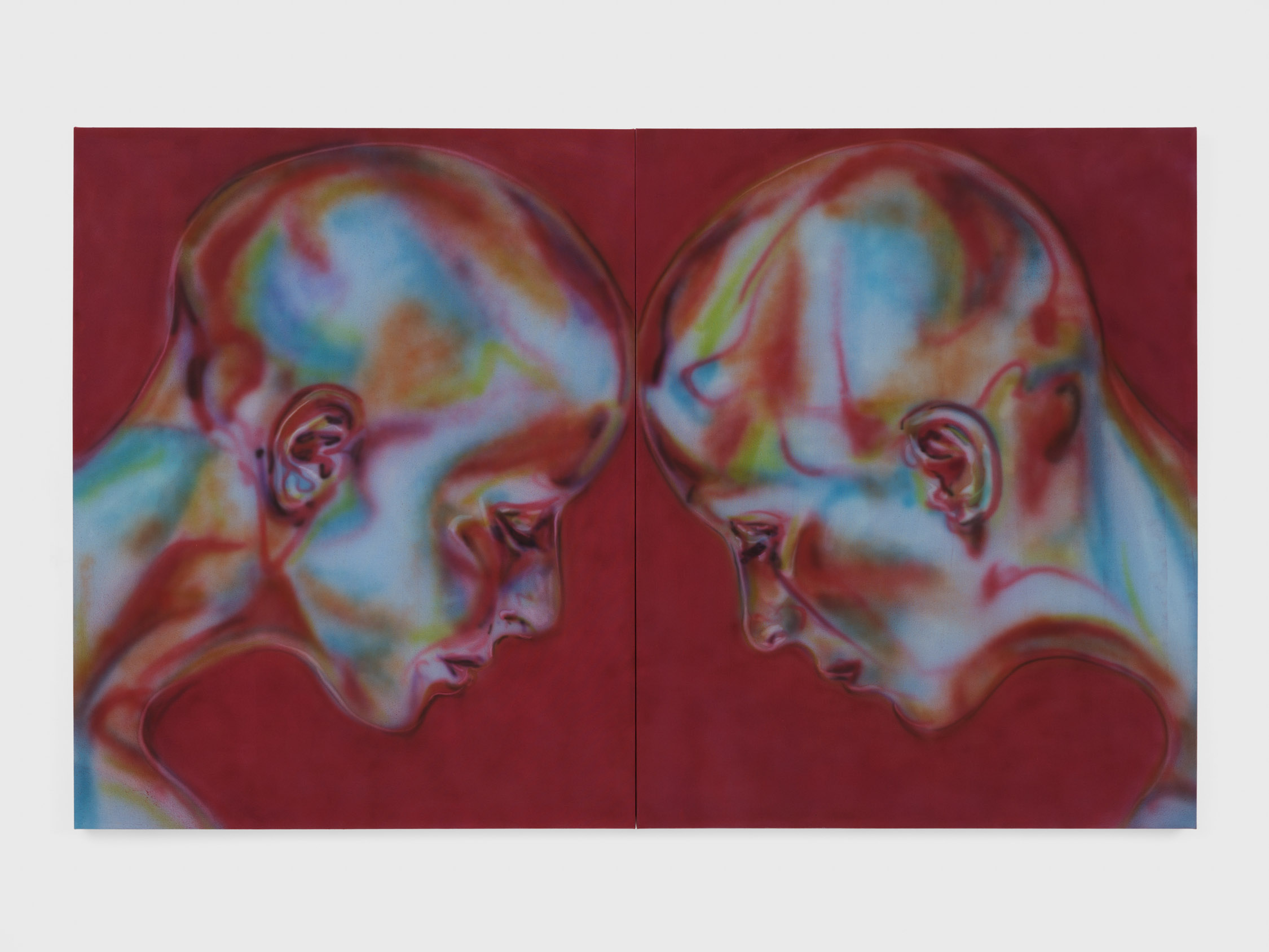

Two heads bow towards one another, haloed in hues of ethereal blue, red ochre, muffled yellow, and screaming fuchsia. Presented against a crimson ground, the figures in the diptych Death makes angels of us all and gives us wings where we had shoulders smooth as raven’s claws (2024), arguably the central work in the exhibition, appear pensive or penitent, whilst the angle of their devotion recalls Durer’s clasped hands. Divorced from context, this representation appears to be that of a single individual in parlance with their own selfhood—or its withdrawal. Presenting the likenesses of friends, acquaintances, and complete strangers, Hector seeks not to aggrandize, but to grieve: the works in Ego Rip labor in opposition to the Western historical paradigm of portraiture as representations of a unified selfhood and opulent dominion, as culminated in 17th to 19thcentury European portraiture. In contrast, Hector’s works are ascetic, bereft, floating, technicolor signifiers hovering over a void.

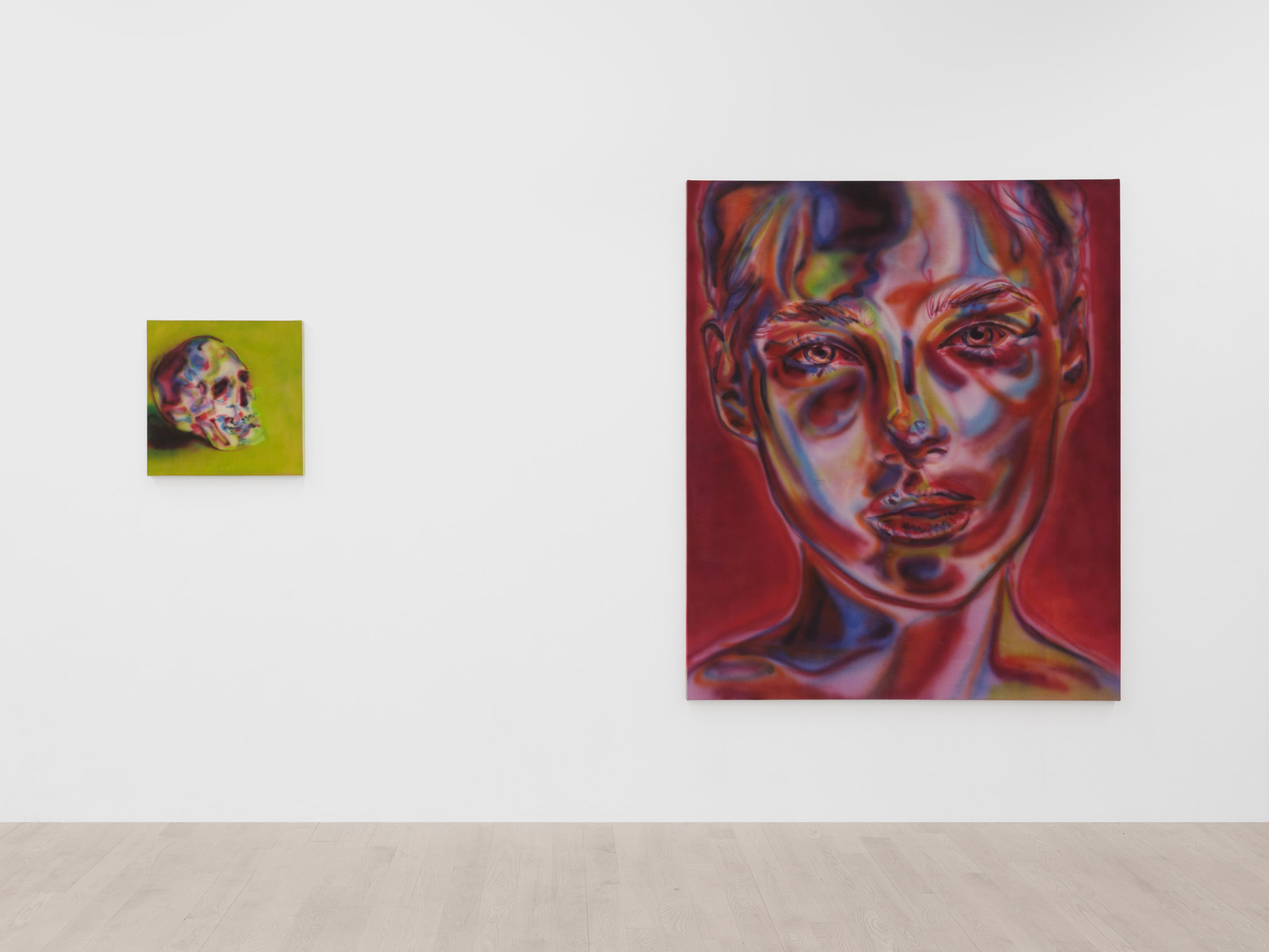

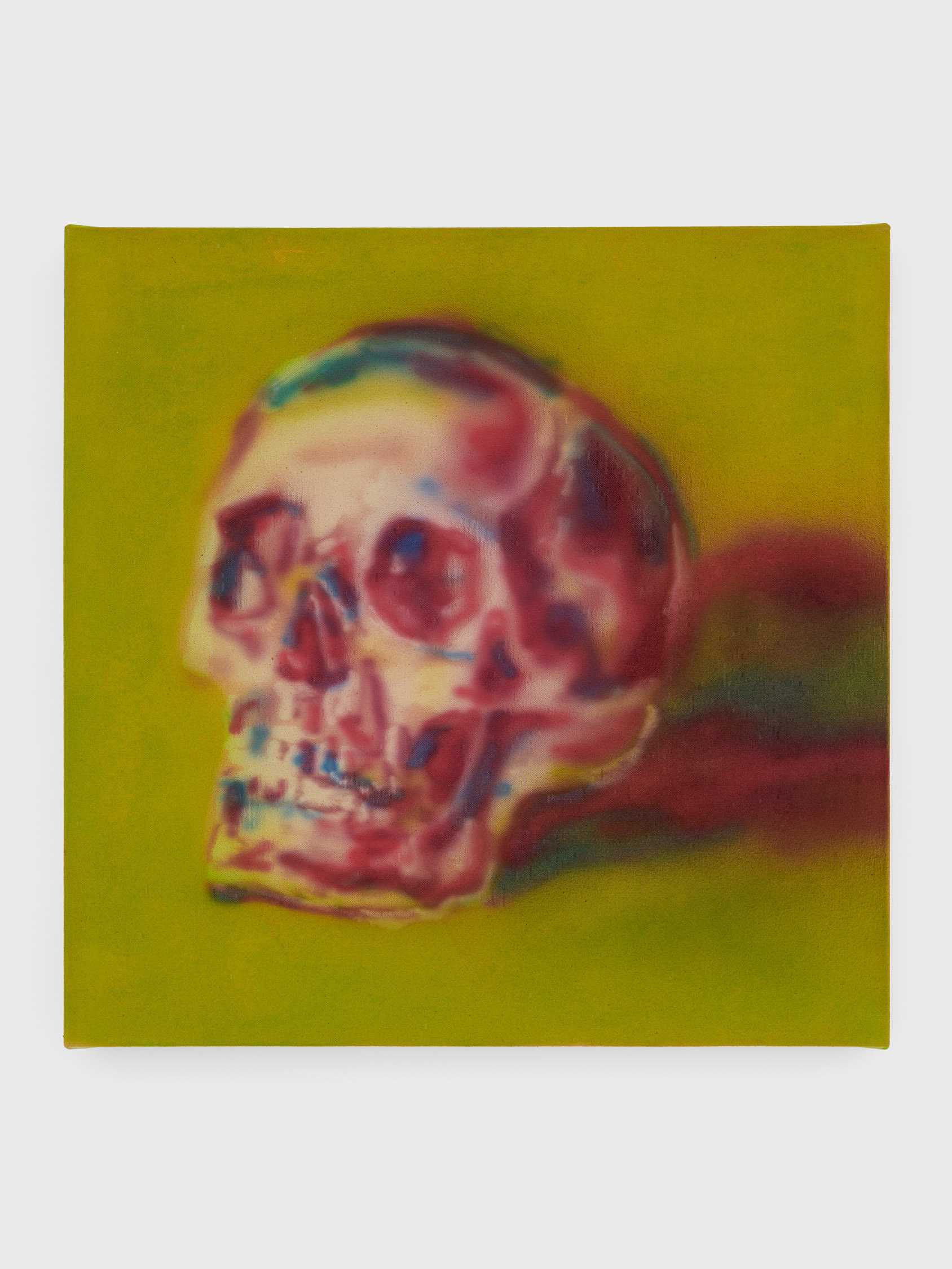

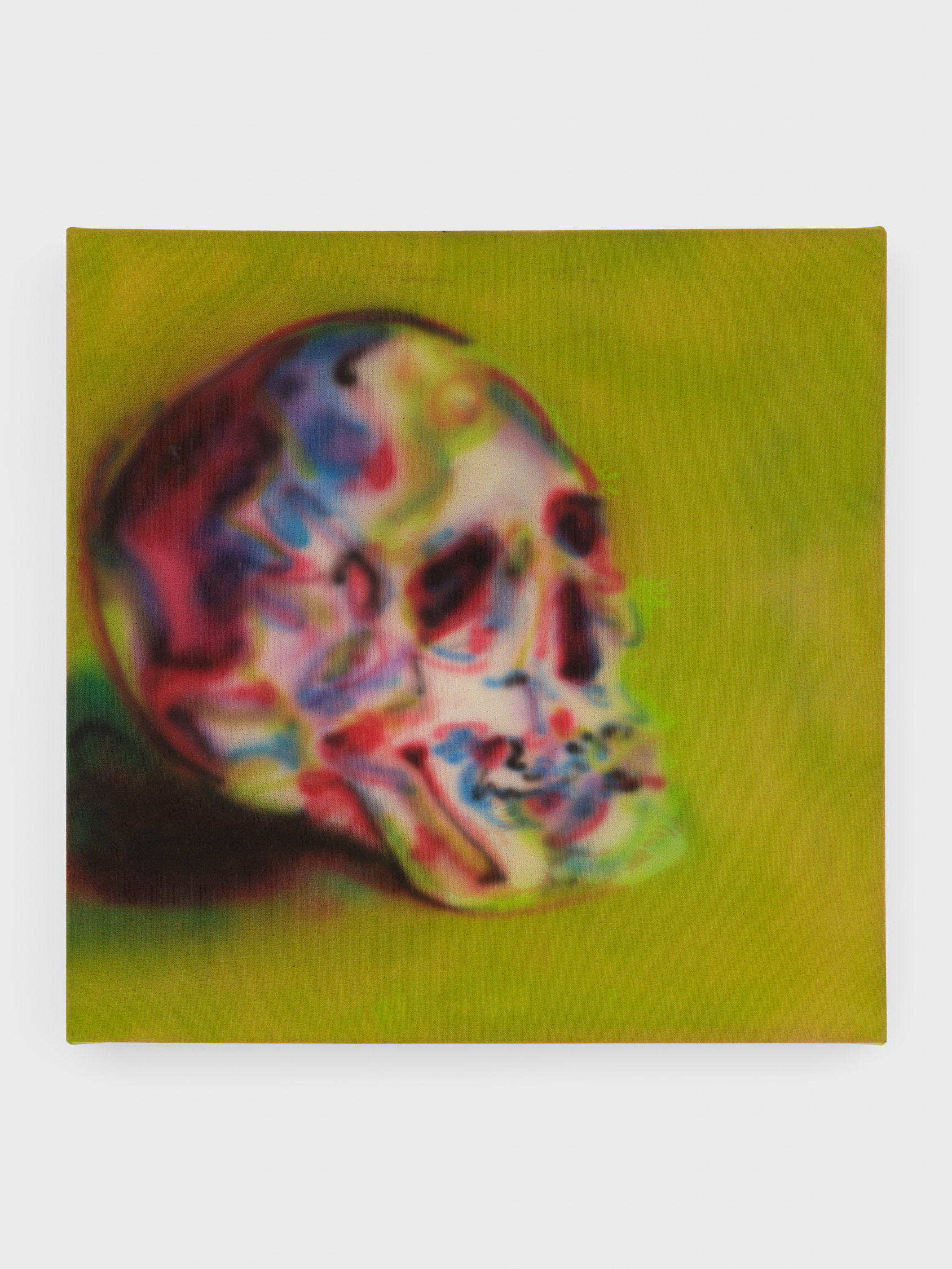

Described by the artist as allegories of the death of the ego and attendant loss of subjectivity—drawn as much from the transformational moment in Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey as from the artist’s journey as witness to her mother’s recent battle with terminal cancer—Hector’s tableaux confess as much as they portray. In the latter case, the artist imparts, “My interest in and perhaps experience with ego death emerged in tandem with my mother’s literal death”. Reflected in the seminal work of Death makes angels… (2024) described above, as well as in the unmistakable though playfully titled skull images of Dead Head I & II (2024), the works in this exhibition doubtlessly and elegantly bear witness to this traumatic maternal passing.

Yet in the former case, the hero’s journey may be the artist’s own. Here, for Campbell, as well as perhaps for Hector, it is the loss of ego that signals triumph, return, or overcoming: a creative re-birth. Taken from the psychoanalysis of Carl Jung, and imbued with Eastern philosophy, Campbell’s ego death is an appealed-to, desired, transcendent state: the sign of transformation. Campbell states in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, “The ordeal is a deepening … the question is still in balance: Can the ego put itself to death? For many-headed is this surrounding Hydra; one head cut off, two more appear, unless the right caustic is applied to the mutilated stump. … Dragons have now to be slain and surprising barriers passed — again, again, and again. Meanwhile there will be a multitude of preliminary victories, unretainable ecstasies, and momentary glimpses of the wonderful land.” In Hector’s work then, the multiplied portraits, not as selfhoods but symbols, point towards her encounter with the hydras on her own voyage towards salvation; yet here, it seems, as bleach pours onto pigment, and the fiber of the canvas is tested, ‘the right caustic is applied.’

However, these somber, uncanny portraits also recall other practices, other histories of the portrait. Presenting slick-hued images that strike the viewer as objectively beautiful yet eerily repulsive, Hector’s chrome toned cheek bones, pigment-saturated lips, and chiseled, blanched jawlines recall the vanity of beauty and indeed, when paired with the skull images in Dead Head I & II, the Vanitas itself. The Vanitas, like memento mori, recall the futility of life and the temporality of earthly pleasures. As a style, often marked by the presence of a skull but otherwise restrained in composition, it reached its apogee in 16th and 17th-century Dutch still life painting. Like Hector’s oeuvre, these works served as allegories of death—the ego notwithstanding.

Likewise, though the zenith of millennia of portraiture may have climaxed in historical memory in the likenesses of power and privilege, the genre’s ancient origins lie in the tradition of the death mask, often cited as derived from 2,000-year-old Fayoum paintings, encaustic likenesses gracing the sarcophagi of Egyptian elites. In Hector’s work, the mask remains and yet the indexical link is lost. Its trace is that of erasure—a bleached lack. No longer does the portrait enact a particular form of identity rendered visible, but rather a condition of alienation, of dissociation: the artist’s oeuvre, perhaps not coincidentally as the work of a female artist, belies the insufficiency of the image or sign to portray (her)selfhood as such. Or, as suggested by the diptych of reflective, bowed heads, whose title consists of a citation from Jim Morrison’s last spoken word album, American Prayer, its only plentitude is an echoing appeal to a void.

— Brooke Lynn McGowan

Katie Hector (b. 1992) in Lawrenceville, New Jersey, is an artist, curator, and writer based near Los Angeles, California. She earned a BFA in painting from the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University in 2014. Solo and duo exhibitions include Ego Rip at Management, New York; Somebody at the untitled void, Seoul, Korea; Cyborgs Never Die at Moosey, London; and Allegories at The Cabin, Los Angeles. Recent group exhibitions include Pillow Talk at LA Beast, Los Angeles; Fembot at The Hole, New York; Reminisce at Hollis Taggart, New York; Twentysomethings at The Orlando Museum of Art, Florida; and Fifty Reds in Their Minds at Red Arrow, Nashville.