Artist: Joan Thorne

Exhibition title: THE GHOST PICKED ME TO PAINT THE SONG

Venue: Freddy, New York, US

Date: October 7 – 29, 2017

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Freddy

This text is an abbreviated version of an essay titled, “The Ghost Picked Me: The Life and Art of Joan Thorne,” by Peter Hastings Falk written in 2010. For more information on Joan Thorne please visit her website: here

It’s like the ghost is writing a song like that. It gives you the song and it goes away. You don’t know what it means. Except the ghost picked me to write the song. – Bob Dylan

Ask Joan Thorne to describe the creative sources of her imagery, and her reply will reflect annoyance tempered by patience. She defers to Bob Dylan, who, when asked the same question, replied, “The ghost picked me to write the song.”

Thorne and Dylan came of age in New York City in the early 1960s. Dylan arrived in 1961, determined to become a unique part of the new folk music movement. By the middle of the decade, his career had taken off. At the same time, Thorne was emerging from the shadows of the Abstract Expressionists, determined to make her own mark on painting.

Thorne grew up in Greenwich Village. Her mother was a Ukrainian immigrant from a musical family, who became an English teacher; her father, a surgeon. Recognizing their daughter’s artistic talents early, they enrolled her at age six in the Little Red Schoolhouse on Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village. Founded in 1921 by Elisabeth Irwin, a pioneer in educational reform, the school has continued to maintain its reputation as a progressive and nurturing catalyst for creative children. Pete Seeger, the folk singer, performed there so frequently that Thorne remembered him as if he were one of the teachers.

The faculty at “Little Red” reinforced Thorne’s role as the school artist. “Year after year, the teachers frequently hung my paintings in the hallway,” she says. “More than that, they really talked to me about them in a serious way. This made me feel that I was engaged in something very important. It was there I became a painter.” At the same time, waves of activism continued to rage: the Vietnam War was exposed as a true quagmire; the civil rights movement marched painfully yet inexorably forward; and, the women’s rights movement announced that a male-centric culture would have to change its ways. But the counterculture was also the generation of love, peace, and psychedelia – just as bent on the spiritual explorations of one’s inner self as it was on exposing society’s ills – all to the music of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. Dylan, too, had transformed himself into a rock musician. With the five members of The Band, he recorded “The Basement Tapes” in a house dubbed “Big Pink.” His lyrics and lines now seemed to float in an ethereal space, as if in counterpart channeling Thorne’s surreal shapes and psychic environments.

In 1971, Thorne met Faith Ringgold (b. 1930) and joined her as a teacher at the Women’s House of Detention on Rikers Island in a new program called “Art without Walls–Free Space.” The program, which had been born from the civil rights movement, was aimed at enriching the lives of the inmates. Ringgold even painted an eight-footsquare mural for the facility. She also encouraged the younger painter to remain true to her inner drive. “I became an artist because I wanted to tell my story,” says Ringgold. “Joan understood that path. Still, when people see her paintings they are constantly trying to relate the shapes and forms to reality. But they can’t be identified because they are other-worldly.

In 1977, Thorne contributed to the first issue of Re-View, likely the first American magazine published, illustrated, and written by artists. Its founder, the painter and writer, Vered Lieb, lauded Abstract Expressionism in her editorial as a “necessary and inspirational part of our national heritage.” However, she reminded the third generation of the New York School that it had a new and higher responsibility. Harking back to art’s role as “the only spiritual counterbalance to a materialistic world,” she wrote that works in Re-View would be “significant and representative of a ‘cultural consciousness’ of our time.” She was confident that the third generation had found itself on a new frontier that was “the fertile ground from which profound artistic expression will arise.” However, Thorne and her peers came of age struggling against sexism in the art establishment and its attendant lack of exhibition opportunities for women. Since 1985, this issue had been loudly exposed by the public protests of the Guerrilla Girls, whose members remain a well-kept secret. By 2006, representation of women at the Whitney Biennial improved to 29 percent, and by 2008 and 2010 to 40 percent. Despite these gains, in May 2009, Jerry Saltz, the art critic for New York magazine, accused the Museum of Modern Art of “a form of gender-based apartheid” because only 4 percent of its permanent collection on display consists of works by women.

The painter, Thornton Willis (b. 1936), a close friend since 1974, explained Thorne’s roots and those of the third generation. “As much as we like to place artists in neat categories, Joan’s art is unique. It comes from a highly personal vision, as does all moving art. For a long time, some conceptualists have been saying that painting is dead, but it remains very much alive. Joan’s energy, and the energy of all great painters, is still coming out of those avant-garde movements of the early twentieth century. Certainly, her roots are in Abstract Expressionism, with surrealist imagery emerging to the forefront. These are our roots. After all, if an artist has no roots in the past, there is no future. With this perspective, Joan has always been respected among artists as a strong painter whose expressions are uniquely her own.”

Her mission is most succinctly expressed, again, by Bob Dylan: “The world don’t need any more songs. There’s enough songs. Unless someone’s gonna come along with a pure heart and has something to say. That’s a different story.”

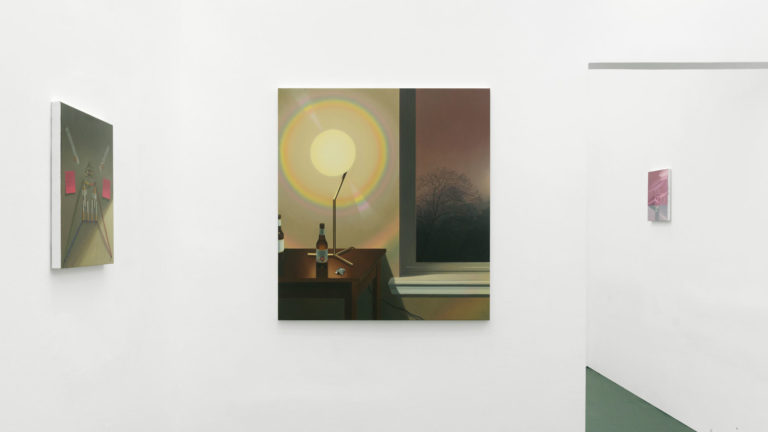

Joan Thorne, THE GHOST PICKED ME TO PAINT THE SONG, 2017, exhibition view, Freddy, New York

Joan Thorne, THE GHOST PICKED ME TO PAINT THE SONG, 2017, exhibition view, Freddy, New York

Joan Thorne, THE GHOST PICKED ME TO PAINT THE SONG, 2017, exhibition view, Freddy, New York

Joan Thorne, THE GHOST PICKED ME TO PAINT THE SONG, 2017, exhibition view, Freddy, New York

Joan Thorne, Firoth, 1982-1983, Oil on canvas, 50 x 50 inches

Joan Thorne, Firoth, 1982-1983, Oil on canvas, 50 x 50 inches

Joan Thorne, Brizet, 1982-1983, Oil on canvas, 50 x 50 inches

Joan Thorne, Brizet, 1982-1983, Oil on canvas, 50 x 50 inches

Joan Thorne, Aba, 1982-1983, Oil on canvas, 53 x 53 inches

Joan Thorne, Aba, 1982-1983, Oil on canvas, 53 x 53 inches

Joan Thorne, Erodo, 1980, Oil on canvas, 50 x 50 inches

Joan Thorne, Erodo, 1980, Oil on canvas, 50 x 50 inches

Joan Thorne, Iba, 1981, Oil on canvas, 54 x 54 inches

Joan Thorne, Iba, 1981, Oil on canvas, 54 x 54 inches