In terms of formal aesthetics, Henning Bohl acts a tragicomic role, playing a forestalled painter whose works permanently relate to painting discourses and even take up painterly strategies themselves, while failing to conform to the deliberate constrictions of the panel and the brush. Instead, Bohl has developed an understanding of painting as an installation art involving disparate elements and materials perceived from a primarily painterly point of view. ‘The Gift’, Bohl’s first solo exhibition after a long silence, weaves together various strands of form, content, and motif, and presents them under personal auspices.

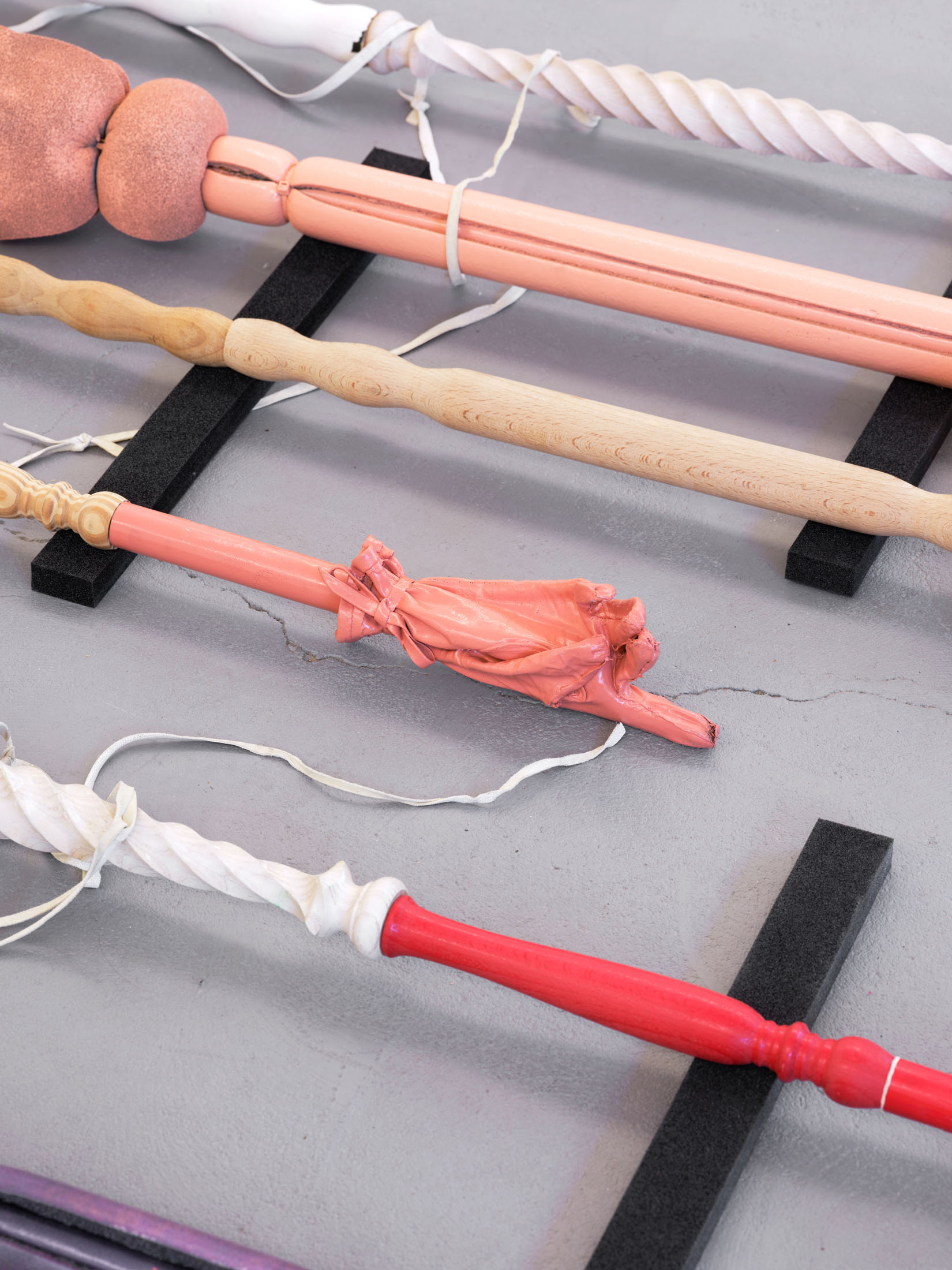

There are the pointers, the gloved, stick-figure arms employing woodturned skeletons and foam flesh, reminiscent of home-made weapons constructed for Live Action Role Playing, or the processional poles of a pagan procession. As their reach into the void becomes a longing for contact, we entangle with the primordial anthropological gesture of the gift.

As given, or not-yet-given goods, the objects resonate with giftedness and forgiveness. Every gift is also the presentation of something that henceforth always sticks, with a range of qualities including closeness, physicality, ownership transfer and refused rejection. In these contexts, Bohl’s cherished yellow cheese boxes, these objects from the realm of the gift themselves, wrapped now with painterly seduction from which gloves have been left limply hanging, perform art’s allegorical anxiety with the future, preparing for an emergence in which the receiver may not properly begin to extract the enormous flow of energy poured into them.

The pictures in the exhibition touch on the themes of anxiety and ambiguity from a different, but similarly allegorical direction. Deconstructing the hortus conclusus, the iconography that describes the virginity of the Saviour’s Mother as an enclosed garden, Bohl’s tidy plantings become a wild growth infecting the corners of houses and the pits of wastelands with lives of their own. The secret garden’s seclusion breeds keyholes and portals that initiate unexpected transitions. Bohl’s pictures perform a peculiar modularity; on the one hand they are connected to each other in a chain, but on the other, like icons in a museum, they become fragments, even amputations from a now lost architectural or cultic context.

The technical realisation of the exhibition’s pictures similarly complicates the relation of aperture to exposure. A painting, even, as in Hinterglasmalerei, occurring directly on the other side of a glass, also has an exposable body, though with special properties. It is happy to invert, to remaining simultaneously transparent and opaque. Drying paint has been cut away from the far surface to make this picture. This fragility of the medium superimposed on all the subjects gathered and arranged is typical of Bohl’s painterly inter-relation of content, material, form and technique.

Newly profaned forms only convey the sacred context of their original embedding as an eternal latency. But in the point of view of painting such concerns are not ends in themselves. They are also a conscious attempt to work against and within the violent rigidity of painting’s usual structuring templates, to wrench agency from the painted figure itself. Bohl does not pose questions from an Olympian standpoint, but implicates his own articulation from within the already highly sociologically-strained figure of the creating artist.

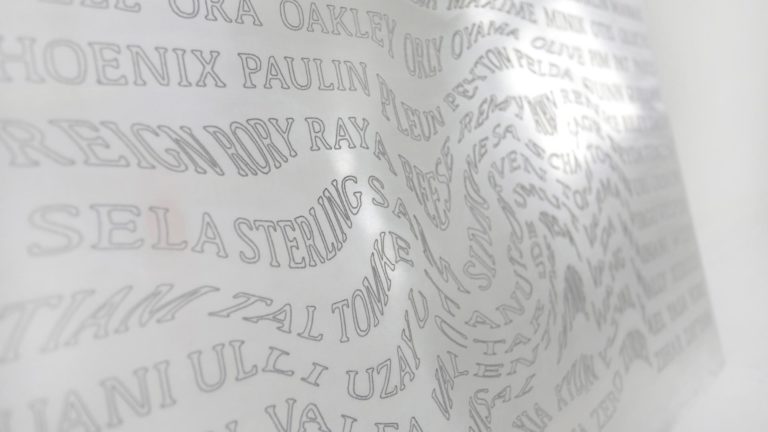

It seems that Bohl is engaging forms that can hold and withstand inner contradictions, and relate to binary models in an always expanding complication. The choice to present the entire project inside a decidedly binary complementary contrast of two colors, funnily enough, overcomes ordinary binary logic in the literal blink of an eye. The yellow and the violet weave together into a consciously enriched set of ambivalences, a growing mass of references that overwhelms the original polarity.

“The Gift” already breathes a certain fragrance of archaic revival in its title, a drift also discernible in the exhibition’s spatial realisations. Associations with icons, processional staffs and grave goods are raised, but without forced regression or implied conformity. Bohl’s aim is not to evoke “the sacred” in its inherent sublimity, but to employ art making as a real cultural technique. He invites us to question, to take ownership, to feel completely addressed, to wonder together with an open allegorical art freed from the rituals of religion, nation, and morality, potentially emancipatory.

Henning Bohl (*1975) studied at the Kunsthochschule Kassel and the Städelschule Frankfurt. In addition to numerous participations in group exhibitions and self-initiated curatorial projects, they have had solo exhibitions at Come over Chez Maliks, Hamburg (2019), Stadtgalerie Schwaz (2018), Blaffer Art Museum Houston (2015), Kunsthalle Nürnberg and Berlinische Galerie (2013), Pro Choice, Vienna (2012) Kunstverein Hamburg (2011), Cubitt London (2010), Kunsthalle Baden-Baden (2009) and Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen and Kunstverein Braunschweig (2005), among others. Galerie Meerrettich, Berlin (2003), Kunstverein Frankfurt (2002). Bohl teaches as professor of painting at the University of Applied Arts Vienna and lives and works in Vienna and Hamburg.