Artists: Jonathan Binet, June Crespo, Lindsay Lawson, Johanna von Monkiewtisch, Michail Pirgelis, Dash Snow, Julie Villard & Simon Brossard

Exhibition title: grounded

Venue: Berthold Pott, Cologne, Germany

Date: June 12 – August 7, 2021

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Berthold Pott, Cologne

The so-called ‘ground of hard facts’ has a fundamental pitfall: It only bears if its foundation itself has a firm basis. The idea goes back to the age-old grounding debate of metaphysics, which recurs in waves. The goal of all its attempts to establish a foundation: to unravel the structure of reality in its foundations, to get to the bottom of the essence of reality. In doing so, classical metaphysical reasoning presupposes the existence of certain fundamental principles. Paradoxically, these are regarded as fundamental precisely when they are useful for justifying other fundamental principles but are themselves neither justified nor justifiable according to objective criteria. It is precisely the absence of their own ground that seems to make them viable as a foundation. If one doubts the resilience of a basis that justifies reality a priori, one inevitably looks into the bottomless pit that provides perfect nourishment for the post-factual tendencies of our present day. While postmodern thinkers established the dismantling of fundamental claims to truth, philosophy today is therefore again increasingly often concerned with defending truth (cf. Markus Gabriel) and once again giving humanism a bit of solid ground under its feet. For anyone who loosens the anchor of all factuality hangs in the air and becomes incapable of action, like David Bowie’s Major Tom: ‘Far above the world / Planet Earth is blue / And there’s nothing I can do.’

The current exhibition at the gallery Berthold Pott brings together works that reveal significant references to the ground. It is by no means about the one single existential ground underlying everything, about the one fundamental question that conditions everything. The ground here is basically always a different one, and often there seem to be several, viable grounds even within one work. In the sense of a new realism, a multitude of fields of meaning are opened up with their very own claims to truth, which naturally intersect, intertwine, and even collide with each other.

In the centre of the gallery space is a segment of a decommissioned Boeing 707. Michail Pirgelis uncovered it from the desert sand at the aircraft graveyard in the Mojave Desert in California. The soot-blackened interior of the work, as well as the surface of the outer skin, are marked by environmental influences – time has unmistakably inscribed its marks on the material. In addition, remnants of the Californian desert sand have accompanied the work, which bears the title Summer Camp and is installed in the exhibition space like a temporary, makeshift dwelling; scattered on the floor, it tells of the eventful past of a found object which, in its former life, travelled to many parts of the world.

With his works, Pirgelis pushes abstraction in such a way that, despite his intense engagement with industrial materials, their context of origin visibly disappears. The idea continues in the work Red Fingers, which is marked by a section of the American flag. As a result of deliberate framing, only three red stripes remain, deprived of their stars. Ready-made to make a lasting impression, Pirgelis’s objects have long since hijacked the potential meaning of their original context. Although they are neither directly from the sky nor far enough out of time, they are not least of all reminiscent of the conquest of the ‘ocean of the air’ that began a good hundred years ago – and revolutionised the view of the earth. In 1928, Hermann Hesse, an early guest of Lufthansa, the company name of which goes back to the aforementioned metaphor of the ocean, wrote: ‘The land of my youth lay whimsically unfolded below me, very wide, very colourful, Lake Constance shimmered pale.’ Or Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, roughly ten years later in Wind, Sand and Stars: ‘The airplane has unveiled for us the true face of the earth.’ From today’s perspective, Pirgelis’s works present themselves not least of all as expendable parts of that global frequent flyer programme that was recently interrupted more abruptly than ever before: Forced to take a months-long break in the wake of the pandemic, suddenly only a fraction of all Boeings and Airbuses were still in the air. Parking spaces for aircraft on the ground became correspondingly scarce, and their rear holds were filled with half a tonne of sand – ballast without which an unoccupied jet would be as cumbersome as many a metaphysical attempt at justification.

Directly opposite in the gallery space, Johanna von Monkiewitsch turns a monumental floor slab into a canvas, a screen for her otherwise immaterial sculpture. The marble pedestal, reminiscent of a classical plinth for a sculpture, becomes a projection surface and contrasts the shallow movement of the light that blows across the ground like the shawl of a light curtain. One can understand both the strengthening of the floor and the tilting of the perspective as a statement; one can find the play of light eerie or promising. Half tomb slab, half window to the sky (through which one does not see nothing, but rather everything – namely the sum of all colours, the white that is the mixture of all visible wavelengths), Monkiewitsch’s installation provides a view of something that, contrary to its spatial orientation, appears supernatural and rapturous.

In contrast, Lindsay Lawson’s small objects, which occupy a good square metre of floor space, are direct and worldly. The American artist went in search of grounds in her adopted hometown of Berlin and picked up what the pavements and streets had to offer. With unpretentious titles, the replicas of her found objects become bizarre souvenirs from the dirty metropolis. It is clear that the obligatory consumer criticism can be read into the dregs of urban city life. But instead of clumsily denouncing the ‘throwaway society’, Lawson’s carefully shaped objets trouvés made of glazed ceramics show a sensitivity for sediment, for the debris of everyday life, the oblique poetry of which can even flash up in discarded slices of pizza or pumps from the Berlin gutter.

The sculptures by the duo Julie Villard & Simon Brossard hardly seem everyday – but rather extra-terrestrial. One of the structures on view in the gallery seems to grow from the wall into the floor like a misguided stalactite. Tentacle-like, striving to connect with its structural surroundings, the algae-like plant remains extremely alien, its connection to the earth fragile. The title of the work, Love Human Smell, reinforces the impression of an alien in close contact with the blue planet. The structure next to it also seems to be still unfamiliar with the ground on which it is based. Carefully groping in front, balancing on a kind of tail extension at the back, the work Dressed Up gives the impression of searching in vain for grounding.

Further in the front of the exhibition space, a clay torso lies prone, as if it had just fallen off the dissection table. Flat on the floor and ostensibly destroyed – whether broken or brutally dismembered – only a washed-out T-shirt holds together what apparently once belonged together. June Crespo’s work explores the configurations of the self with a focus on the disruptive dynamics that constantly work against all of our personal integrity and physical intactness. For the artist, the human body is a self-contained but always broken form.

In the case of Dash Snow, whose work at first glance seems somewhat out of concept, the reference to the ground is initially of a biographical nature: As a descendant of the New York De Menil clan, the artist broke very early with the high society into which he was born and henceforth sought his own grounding in subculture and the underground. With the medium of collage, which was his favourite along with photography, Snow also chose a working method whose basic principle is to assemble decontextualised material on foreign backgrounds in such a way that new structures of meaning emerge – perhaps almost as he did for himself when he so resolutely broke away from his own social environment.

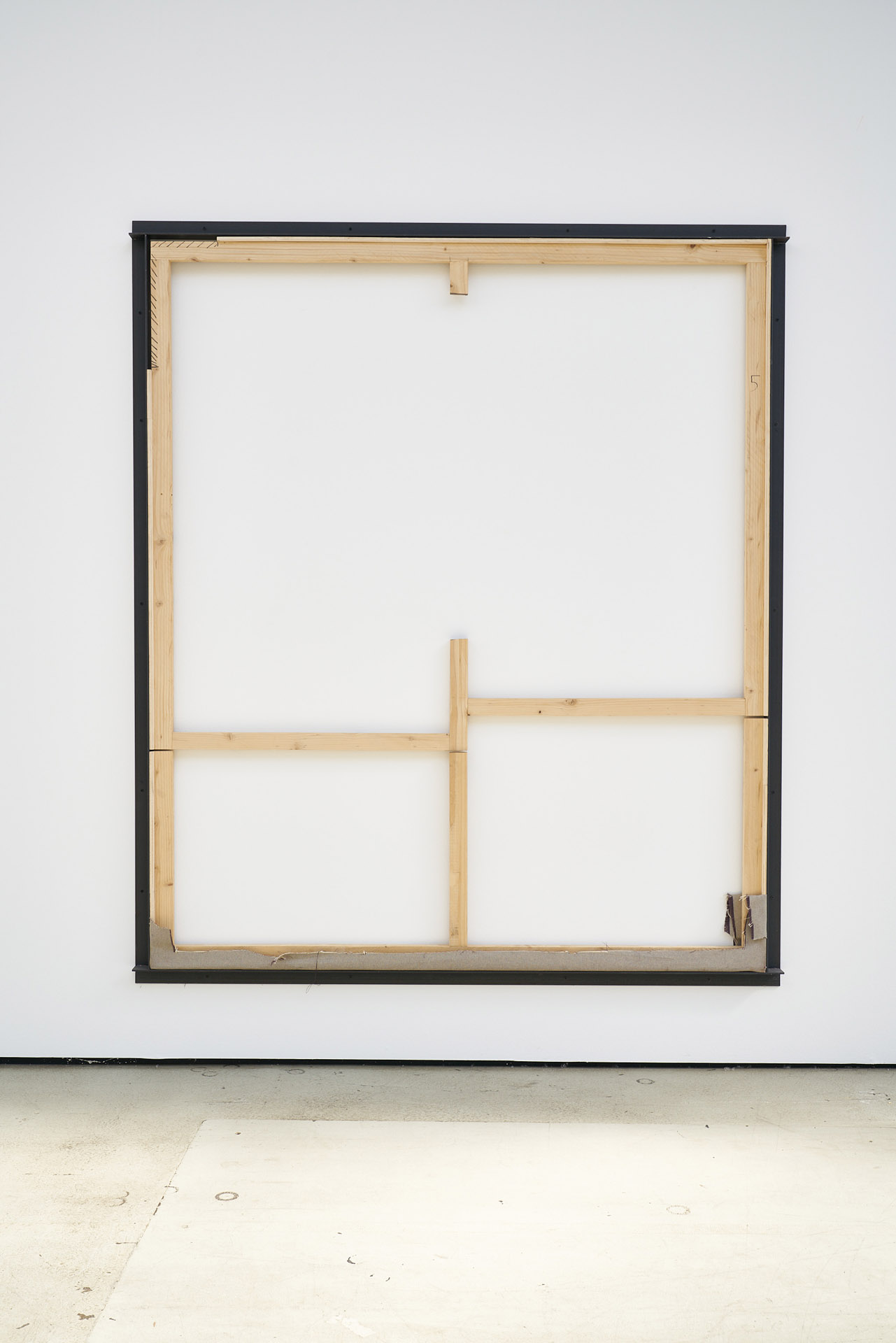

Jonathan Binet makes a radical cut of a different kind when he cuts a canvas from the stretcher frame in order to expose the latter together with the lath cross – in other words, the basic structure of the classical panel painting. In the view of the wall module behind it and its own ‘behind’ (the ‘edge of the picture’ gives a view into the front area of the exhibition space), there is a suggestion of a nesting of levels that is distantly reminiscent of the diagrams which Alfred North Whitehead once used to explain (meta)physical relationships of extension (cf. Whitehead: Process and Reality). To explain his elusive ideas of three-dimensional space, he used the image of the Russian matryoshka. This epistemological bottomless pit follows the same logic as the phenomenon of a ‘doll in a doll’ or a ‘picture in a picture’, also known as mise en abyme or the Droste effect. Every attempt at justification brings to light umpteen new grounds; every fall to the ground can uncover a new cosmos.

-Anna Sinofzik

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Michail Pirgelis

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Dash Snow

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, June Crespo

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Lindsay Lawson

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Julie Villard & Simon Brossard

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Julie Villard & Simon Brossard

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Julie Villard & Simon Brossard

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Michail Pirgelis

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Michail Pirgelis

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Michail Pirgelis

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Michail Pirgelis

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Michail Pirgelis

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Lindsay Lawson

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Lindsay Lawson

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Jonathan Binet

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Jonathan Binet

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, 2021

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Johanna von Monkiewitsch

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Johanna von Monkiewitsch

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Jonathan Binet

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Jonathan Binet

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Jonathan Binet

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Jonathan Binet

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Jonathan Binet

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Dash Snow

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Dash Snow

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Dash Snow

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Dash Snow

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Dash Snow

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Dash Snow

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Michail Pirgelis

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Michail Pirgelis

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Michail Pirgelis

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Michail Pirgelis

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Michail Pirgelis

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Michail Pirgelis

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Michail Pirgelis

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, June Crespo

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Julie Villard & Simon Brossard

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Julie Villard & Simon Brossard

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Julie Villard & Simon Brossard

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Julie Villard & Simon Brossard

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Lindsay Lawson

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Lindsay Lawson

Installation view grounded at Berthold Pott, Cologne, Lindsay Lawson