Artists: Anne Collier, Cerith Wyn Evans, Yngve Holen, Sergej Jensen, Klara Lidén, Albert Oehlen, Andreas Slominski, Reena Spaulings

Exhibition title: grabt tiefer, ihr Schönen

Venue: Galerie Neu, Berlin, Germany

Date: November 4 – December 7, 2016

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Galerie Neu, Berlin

The garish colors, bizarre motifs and strange proportional relationships in digital collages from 1998 by Albert Oehlen herald a world run amok. Even today, twenty years later, the absurd pleas of Oehlen’s so-called ‘posters’, with their agitprop aesthetic, still irritate the viewer. At the same time, they could hardly be more pertinent: “dig deeper, you beauties, and you will get lucky.” “Hail Europe.”

Oehlen’s work provides the point of departure for a group exhibition at Galerie Neu that brings together older works with new pieces, some exhibited for the first time; together, this ensemble initiates associative, intersecting paths that circle around the theme of a destabilization of a seemingly stable, hegemonic value system.

Since 2004, Reena Spaulings has explored the fluid boundaries between art and the market. She has rigorously called into question the identity constructions and identifications that inhere in the art-market constellation. A mirror is held up to society. A garbage bag is waved back at the current, growing, global rise of nationalism.

Yngve Holen launches a new body of work here with his piece Platooning (2016). The sculpture builds on Holen’s investigations of contemporary relationships between man and machine, the fetishization of technology as status symbol, and the question of how high-end consumer technology products are distributed. The door of a van, sprayed in gleaming Lamborghini car lacquer, hangs on the wall like a hunting trophy. Gutted and exploited.

Across from Holen’s work is Sergej Jensen’s Geometric Nightmare (2007), which threatens to consume the entire length of the wall. Spindly white threads weave through the painting’s surface like a network of scars, holding the plane together. The monumentality of this abstract nightmare confronts the viewer with his or her own (well founded?) fears and bad dreams. The work offers neither a lifeline nor a solution.

The heads of the contorted naked women that appear in Anne Collier’s photographs Endpapers #1 (Photographing the Nude) (2016) and Endpapers #2 (Photographing the Nude) (2016) are cropped off. This depersonalizes the figures and objectifies them in one swoop. Collier deploys photography to investigate the question of how femininity has been framed in print and popular culture over the last few decades. She recontextualizes and thus reformulates the original context of an illustred book in order to create a narrative of her own. When does the staging of a nude, female body act as an expression of misogyny and when does it initiate liberation?

Andreas Slominski’s new work, Toilettenpapierhut (2016) continues the subtle and ambiguous exploration of the social values of rooms, objects, and identities that ran through his exhibition this past summer at the Deichtorhallen in Hamburg like Ariadne’s thread. This new work refers snarkily to the West German penchant for concealing rolls of toilet paper in crocheted containers.

At the same time, the pedestal supporting the work – itself a sculptural object, which positions a work in the exhibition context and also assigns it an increased value – is made out of pieces of a portable plastic toilet.

Klara Lidén has transformed a used wooden fence into a piece of furniture. She thereby conflates and confuses the boundary between interior and exterior, as well as the ideological separation of private and public space. The fence functions as a screen, behind which a seemingly private seating, or sleeping arrangement is nested. The structure of the fence, which is intended to prevent people from penetrating into private, supposedly inaccessible spaces, becomes relativized. Simultaneously, the work poses the question of who has access to specific spaces and how spatial boundaries (both small and large) are defined.

These considerations crystallize in Cerith Wyn Evans’ neon work. In white letters, the word TIX3 (1994) hangs above the gallery door. As an indication of an exit, however, the mirrored script is misleading: One would only be able to view the piece from the “correct” side if one had already exited.

Cerith Wyn Evans, TIX3, 1994, Neon, 14 x 34 x 2 cm

Sergej Jensen, Geometric Nightmare, 2007, Various fabrics, thread, 380 x 450 cm

Anne Collier, Endpapers #1 (Photographing the Nude), 2016, C-print, 126.2 x 180.34 cm

Anne Collier, Endpapers #2 (Photographing the Nude), 2016, C-print, 126.2 x 179.58 cm

Reena Spaulings, Untitled, 2005, Plasticbag, nylon fabric, aluminium, 90 x 152 cm

Yngve Holen, Platooning, 2016, Metal, car varnish, 220 x 265 x 32 cm

Andreas Slominski, Toilettenpapierhut, 2016, Wool, toilettpaper, plastic, rivet, plexiglas, 165 x 102 x 102 cm

Albert Oehlen, Europa, 1998, Computer print, 125.7 x 177.3 cm

Klara Lidén, Chaise Clôture, 2016, wood, concrete, metal, 199.6 x 203.2 x 85.6 cm

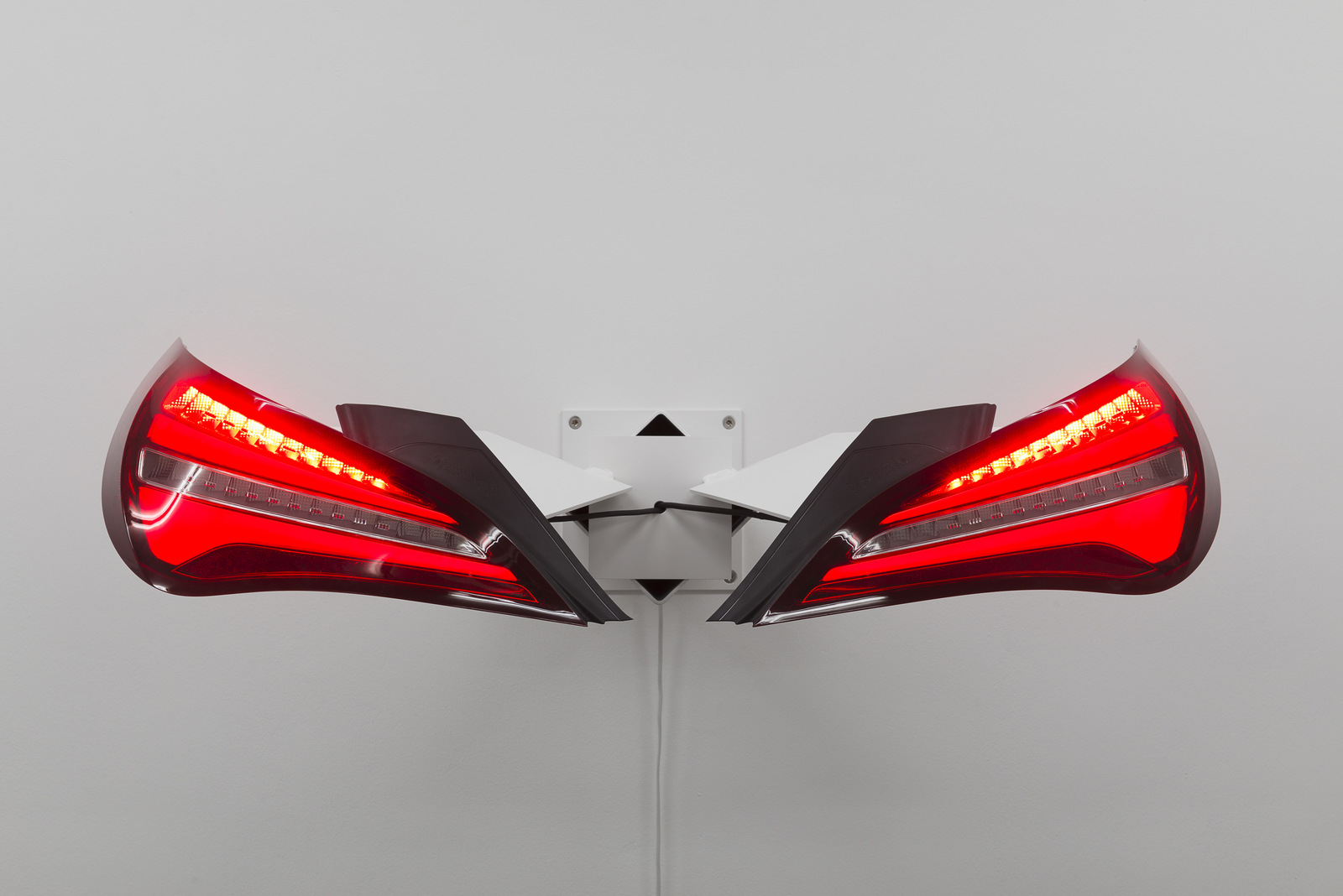

Yngve Holen, Hater Taillight, 2016, Autobus Headlight, Powder-coated steel, 28 x 105 x 90 cm

Yngve Holen, Hater Taillight, 2016, Autobus Headlight, Powder-coated steel, 28 x 105 x 90 cm