Artist: Gili Tal

Exhibition title: For the Sake of Those Who Would Discriminate Between Hallucinations

Venue: Galerie Buchholz, Berlin, Germany

Date: June 19 – August 15, 2020

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Galerie Buchholz Berlin/Cologne/New York

I was going to write about how this is all about streets. And the way that new ones seem to just appear, as if from nowhere. Which they do, and always have. All that being as it may, I think it’s more about photography again, or particular genres of it, like the commercial ones from the world of real estate, which for that matter covers art exhibition photography as well, and the way that both of these deploy various dramatic tropes such as the recessive effects of vanishing points. Bourne of single-point perspective, techniques like this are also broadly familiar from the world of cinema, where a plunging view point effectively draws the viewer into the frame. But in terms of commercial photography, such means have at least one other convenient side-effect at their disposal, like the added value begot by the new-found sense of dynamism that’s now inhered in the picture.

Or failing that, at least what comes of the mere fact of a declaration, or communiqué, that it is indeed there to be found, even if you can’t quite make it out in terms of actual content.

Corridors have long been described as less spaces, more channels, of communication. On their way to somewhere else, people, things and messages pass through them, supposedly in both directions. Architectural theorist Mark Jarzombek has written at length on how from the 17th-century on the corridor became the organising structure of the modern large-scale edifice, public or private. Touching on notions of the ‘romance of connectivity’, he said that the corridor should be regarded as a ‘programme’ rather than a structure, since it ‘recodes’ the building which contains it with the terminology of couriered messages. In which case each opening off it might constitute an address, or even a url. This expectation of the acquisition of some kind of new knowledge upon finally crossing the desired threshold can’t help but imbue such spaces with a particular emotional latency, even if, or precisely when actually, its actual delivery is deferred because said threshold simply multiplies and becomes the next one along in the queue.

When I said this is more about commercial photography, it could be better to be specific and write about how it probably stemmed more from the latter kind that I mentioned, art exhibition photos, and looking at them online. Plucked out from their feed and spread out to appear en-masse, what presents itself in the end is a series of endless hallways. A panorama of frozen white interiors shot at achingly austere angles, their signalling that they want to transmit a piece of information outwards finds a gap where that information should be and leaves nothing much more than a roll-out of walls and slightly mournful perspectives. What is posed as an outward move reaches in. But then, corridors have always had a sort of tension at heart. Variously vaunted for both their utopian potential to connect, or opposite one for opening unto a private occluded world where before there was none, they’ve been given credence for their mysterious interplay of open and closed meanings1. It’s maybe possible for said interplay to keep on going. There’s been enough written on arcades etc and their bleeding of indoor and outdoor space, and what that does. But in terms of the reality, when looking down a new street just appeared, it’s hard not to notice that its traffic tends to be moving one way.

-G.T.

[1] I am referring to the transformation of domestic interior architecture that occurred across 18th-century Northern Europe, where the appearance of the corridor in the houses of the bourgeoisie meant that rather than traverse the house from one room to the next, tangential hallways now circumvented them to create a new kind of privacy for the affluent.

Where would I be without you?

When I drew back the curtains I couldn’t see out, as there are shutters on the outside made up of wooden slats. There is a mechanism for raising them that is hidden behind the curtain, but it’s broken. I check the bedroom, it’s the same. I check the bathroom, there is no window. In the kitchen there is a frosted window above the sink.

It doesn’t open, but along the top there is a small vent. I climb onto the counter to look through, there’s no blind, just a wall.

I ring my mother to tell her about the problem and she asks if it was like that when I viewed the flat. I tell her that I think I viewed it at night. She advises that I call the building manager. I ask if she could do this, as I don’t like talking on the phone. She calls them, then she calls back. They’ve disabled the shutters whilst they do maintenance work, it’s for the good of the building and it shouldn’t take more than a week.

It’s been three. I call back. I tell her I need some natural light, as it’s not healthy. I tell her to tell whoever that if they don’t sort it out soon I’m going to take a hammer and smash holes in the shutters. My mother tells me that would be bad for the building. I tell her this is bad for me. She suggests a SAD lamp.

Another five days pass, I ring again. She tells me they said it would be ready yesterday. Annoyed I reply that it’s not. She tells me I’ve become unhealthily obsessed with the building and encourages me to pay more attention to the city inside my head, as that is where the architecture of possibility resides. I tell her I’ll do my best.

Four days later a man comes round to tell me that the problem they were having was due to the varnish. The maintenance team rolled them up too early and its clogged up the mechanism. So now they had to strip it all back and clean out all the sprockets and cogs, which they’d almost done. He apologised for the inconvenience and I told him it was fine, I’d got used to it.

Another week passes and I ring my mother. She tells me I better not be ringing to complain about the blinds, I wasn’t, I was just ringing to see how she was. At the end of the conversation she informs me that they’d finished cleaning the mechanisms and they were going to turn the power back on tomorrow. I repeated that that was not why I was ringing.

Three more days pass, I’ve heard nothing so I’ve ignored the blinds and got on with other things. At noon the maintenance man comes round to ask if the blinds are working. I tell him I don’t know as I’ve not tried them. He encourages me to give them a go, I tell him I’m too busy.

Another week goes by, my mother calls and asks why I didn’t open the shutters for the maintenance man. I tell her I didn’t want to, I’d got used to living without natural light. She tells me to stop being silly, as everyone needs natural light. I tell her I have my lamp, even though I didn’t actually buy one, but still she seems unconvinced.

Over the next few months various people concerned with the management of the building contact me to ask me to open the blinds. I refuse, I’ve bought curtains and have employed coloured lighting to create an oasis of calm. My mother tells me my luminous interior sounds unhealthy and that the building management have become suspicious. I tell her that that’s their problem.

More months pass and due to unnecessary pressure regarding my tenancy I’m made to agree that someone can come round and test the blinds. A maintenance man arrives for the event, along with my mother. It’s the first time she’s visited and on entry she wastes no time, going straight for the curtains. Once drawn she turns the small key, a loud clattering noise alerts us that the shutter works, and tantalisingly it slowly moves up to reveal a wall.

I catch a look of concern on my mother’s face before we go into the bedroom where the same ceremony ensues. She pulls back the curtains, turns the key and the blind stutters up to reveal yet another almost impossibly close wall. I follow them into the bathroom where there is no window. Finally we arrive in the kitchen where the maintenance man alerts us to an ingenious latch on the inside of the window frame. He releases it and despite me telling him that there really was no need, he slides up the frosted window, to reveal what I already knew.

-Oliver Corino, 2020

Gili Tal, “Inward Looking”, 2020, painted steel, raw steel, plexiglass globes, electrical components, light bulbs, 300 x 144 x 35 cm, 249 x 120 x 33 cm; “Windows”, 2020, digital print on canvas, 130 x 135 cm, installation view, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin 2020

Gili Tal, “Windows”, 2020, digital print on canvas, 130 x 135 cm

Gili Tal, “Inward Looking”, 2020, painted steel, raw steel, plexiglass globes, electrical components, light bulbs, 300 x 144 x 35 cm, 249 x 120 x 33 cm, installation view, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin 2020

Gili Tal, “Inward Looking”, 2020, painted steel, raw steel, plexiglass globes, electrical components, light bulbs, 300 x 144 x 35 cm, installation view, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin 2020

Gili Tal, “Inward Looking”, 2020, painted steel, raw steel, plexiglass globes, electrical components, light bulbs, 290 x 144 x 35 cm, 282 x 144 x 35 cm; “Blinds”, 2020, digital print on roller blind, 5 x 130 x 7.5 cm, installation view, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin 2020

Gili Tal, “Blinds”, 2020, digital print on roller blind, 5 x 130 x 7.5 cm

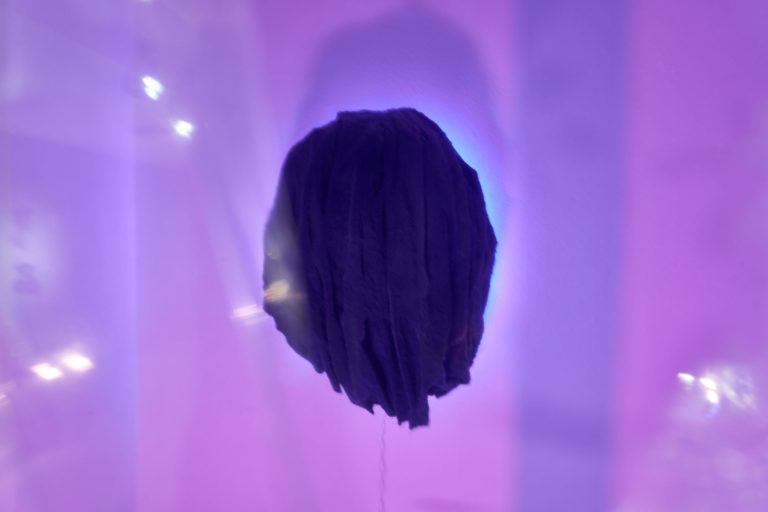

Gili Tal, “For the Sake of Those Who Would Discriminate Between Hallucinations”, installation view, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin 2020

Gili Tal, “For the Sake of Those Who Would Discriminate Between Hallucinations”, installation view, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin 2020

Gili Tal, “Windows”, 2020, digital print on canvas, each 130 x 135 cm, installation view, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin 2020

Gili Tal, “Windows”, 2020, digital print on canvas, 130 x 135 cm

Gili Tal, “Windows”, 2020, digital print on canvas, 130 x 135 cm

Gili Tal, “Windows”, 2020, digital print on canvas, 130 x 135 cm

Gili Tal, “For the Sake of Those Who Would Discriminate Between Hallucinations”, installation view, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin, 2020

Gili Tal, “Inward Looking”, 2020, painted steel, raw steel, plexiglass globes, electrical components, light bulbs, various dimensions, installation view, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin 2020

Gili Tal, “Inward Looking”, 2020, painted steel, raw steel, plexiglass globes, electrical components, light bulbs, various dimensions, installation view, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin 2020

Gili Tal, “Inward Looking”, 2020, painted steel, raw steel, plexiglass globes, electrical components, light bulbs, various dimensions, installation view, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin 2020

Gili Tal, “Blinds”, 2020, digital print on roller blind, 5 x 130 x 7.5 cm, installation view, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin 2020