FLORIN MITROI: CH. I: WINTER

Curated by Erwin Kessler

The most discreet and decent Romanian artist, Florin Mitroi, left the most indiscreet and violent work. What to do with it? Should we hide it, ignore it, classify it as a pathology? Shall we burn it? This seems like the preamble to a scandal, not a revelation. And yet it is about the most electrifying revelation of Romanian art in the last 30 years.

Between 1961 and 2002, Florin Mitroi was a professor at the Nicolae Grigorescu Art Institute in Bucharest. During the first 15 years, he engaged (like any serious and harmless artist of the time) in that modernist routine called “contemporary art”, producing pleasant works, dealing with tolerable subjects, having zero impact on life – a mere intellectual decoration. It was the ideal recipe of any impostor, who professionally claimed the vocation to reach, precisely, the pension. Florin Mitroi was a typical citizen without attributes in the communist system.

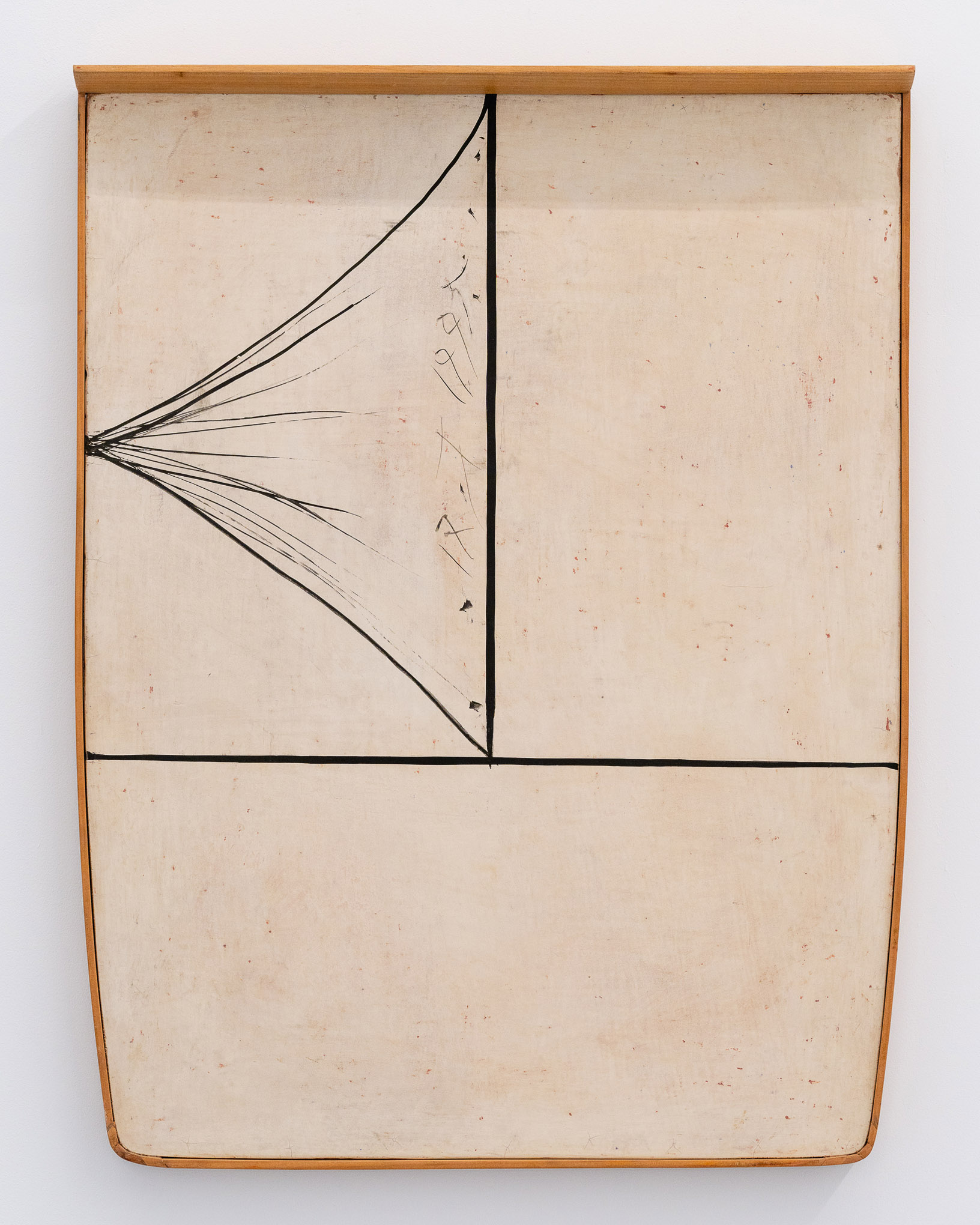

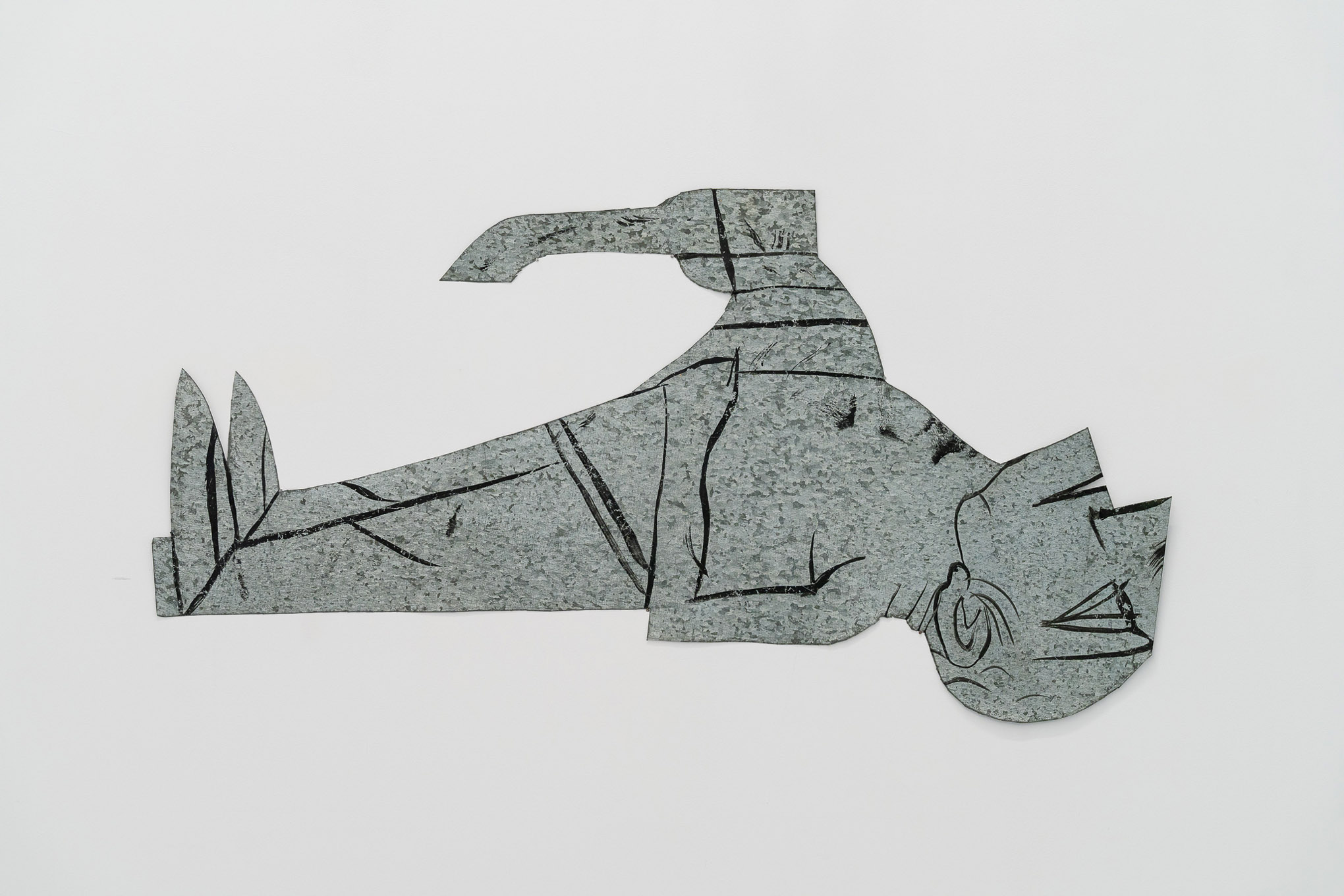

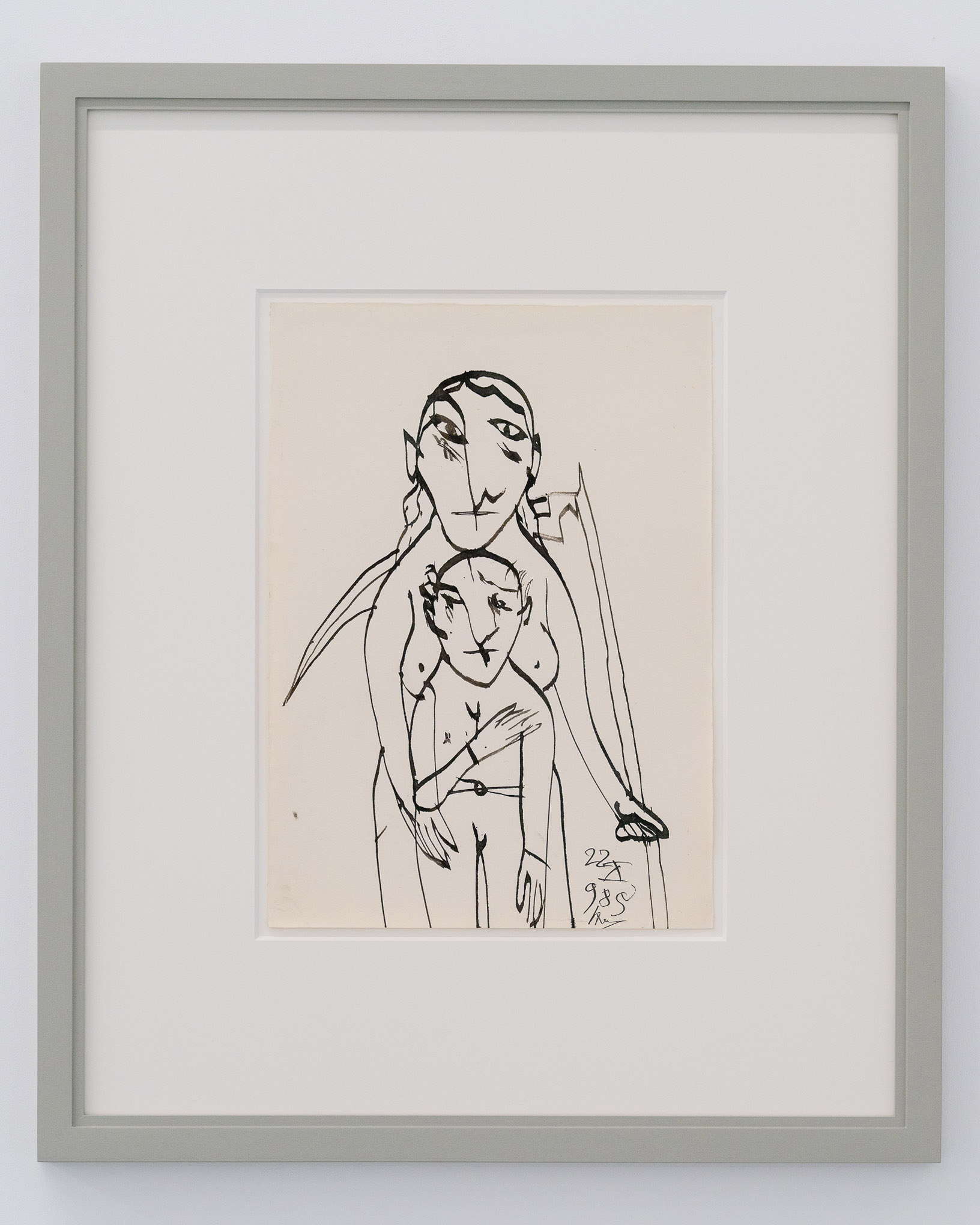

But suddenly, exactly 50 years ago, starting from the winter of 1974 and until his disappearance, in April 2002, Florin Mitroi continuously produced thousands and thousands of works (over 8000) in which the central theme was death, his own death, a perpetual suicide assisted by fatal eroticism. Figures representing the artist with a noose around his neck, with a knife thrust into his rib or an axe crushing his head and chest, or mercilessly courted by naked women with sagging breasts and sharp scythes, proliferated in his compulsively dated works, like a diary of one’s own (con)damnation. Later, to the daily spectacle of his own anguishes, the artist added a legion of witnesses and torturers – foolish figures and sick, corrupt characters, stirred up by philistinism and hatred, by cunning hypocrisy or felonious carelessness. No biographical circumstances explain this somber turn. The artist was neither sick, nor pursued by the communist Secret Services, nor in love, nor unemployed. His parents had not died, and his son was to be born. Everything was as it should be.

In flagrant opposition and total, formal and moral disagreement with his contemporaries, but especially in contrast to the superficial progressivism of the numerous neo-avant-garde artists of the time, Florin Mitroi turned to the most retrograde artistic techniques possible, from painting on wood to tempera painting on glass, like the icons made by peasants of yesteryear. Florin Mitroi’s retrograde technical choice was entirely consistent with his exclusive option for the most reactionary and indigestible iconography, for death and sex – themes forbidden during communism and snubbed now, in full consumerism.

The immediate effect of this major thematic, technical, formal and moral turn of Florin Mitroi in 1974 was the refusal to exhibit. He created and kept his work in solitude and secrecy. No one, not even his family or the students, had any idea about what the artist was doing in the atelier, where he spent his whole life, day by day, from morning to night. In his case, exhibiting was equivalent to self-display – that’s why Florin Mitroi’s only solo show took place in 1993, an acte manqué for which he never managed to forgive himself.

Florin Mitroi: Ch. I: Winter, at Ars Monitor, the first of a series of four, is, from the start, illegitimate. Illegitimate in relation to the artist, to his discretion and mystery, but also to the incredible complexity of his work. Like any exhibition, it is a dissection, a beheading. But it is not illegitimate in relation to the intimate quests of each of us. 50 years ago, Florin Mitroi chose to be self-harming in order not to be a traitor. Making such a choice at the present time is even more difficult than in 1974. The temptation to consider that all evil leads to good is much greater in consumerism than in communism.