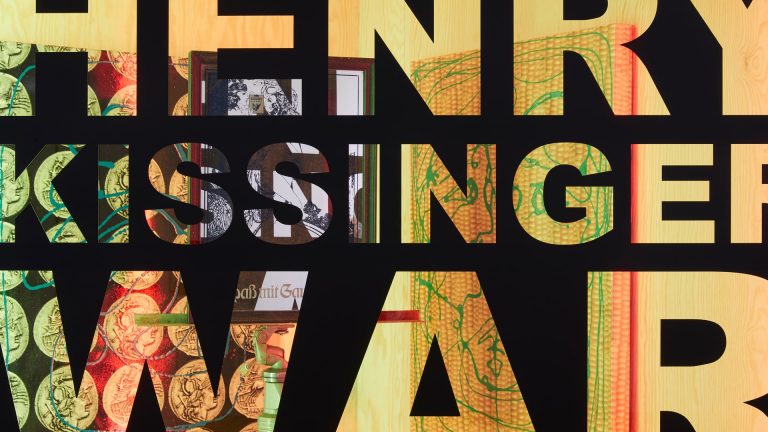

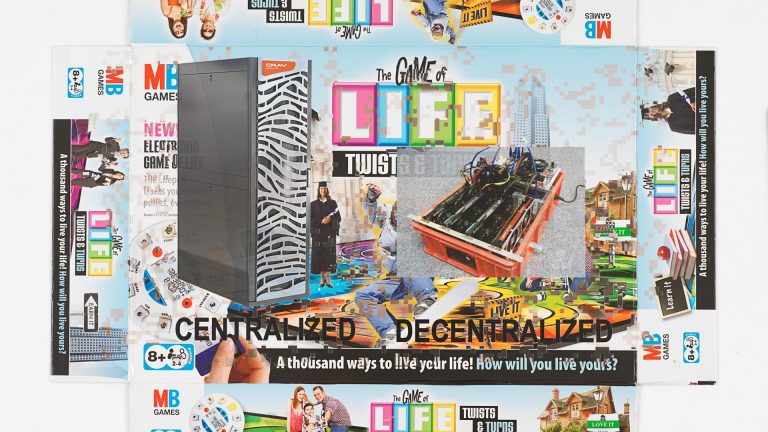

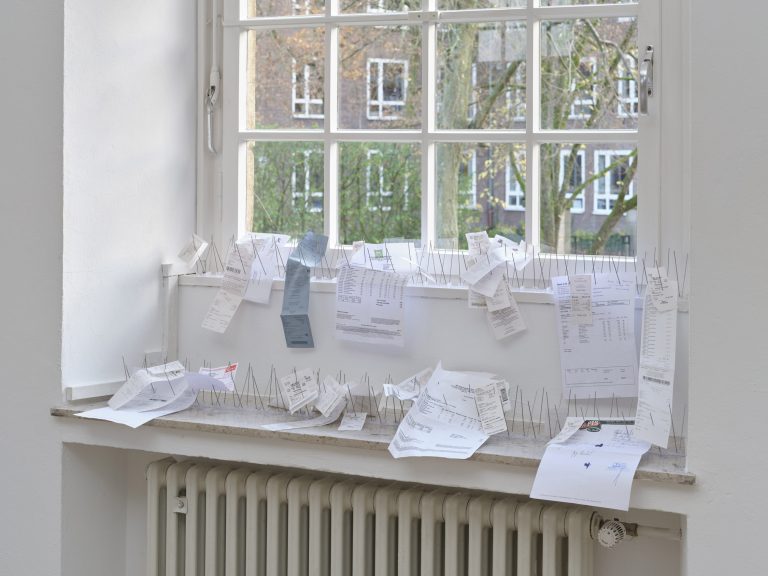

Artists: Maximiliane Baumgartner, Herbert Fiedler, Marieluise Fleißer, Heike-Karin Föll, Stefan Fuchs, Karolin Meunier, Ariane Müller, Sophie Reinhold, Monika Rinck, Daniela Seel, Anne Speier, Jasmin Werner, Alex Wissel

Exhibition title: Ein Pfund Orangen

Curated by: Philipp Reitsam

Venue: Kunstverein Ingolstadt, Ingolstadt, Germany

Date: June 28 – August 1, 2019

Photography: Marc Doradzillo / all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Kunstverein Ingolstadt

A Pound of Oranges, which was more of a luxury good in the 1920s than it is today, symbolizes a short relief and comfort, as well as an unnamed „girl’s“ attempt to reach self-determination and thus happiness. It is about a young woman who craves to be appreciated by her ex-boyfriend, who has lost interest in her. On the one hand, he openly brushes her off, on the other, he doesn’t refrain from using violence to satisfy his desires. This young woman is convinced that she needs a husband, a master to raise her social status and to fulfill the material wishes her friends, who often seem more like competitors, and the protagonist are longing for. She is simply unaware of a possible deeper meaning to life and has always been a dependent person who needed sup-port.

A Pound of Oranges metaphorically shows a failed attempt to brighten up one’s life or to make it at least bearable by the false illusion of superficial admiration. Needless to say, the oranges and all the great dreams of apparent affluence don’t cure the young woman’s depression. Her ex-boyfriend, whose character remains blurry and intangible due to his indifference and distan-ce to his “girlfriend“ and her fatal material and emotional dependence on him, doesn’t offer any way out of her sense of confinement and her impotence to develop freely in a hostile social and economic environment, where women aren’t taken seriously, but put down and humiliated. The main character’s final wish is to break free from this corrupted society. To her, committing sui-cide is the only escape from the deadlock: “It would be a never-ending story for her, no, she had to put a violent end to it. The prospect of the free decision to leave this world in order to go to a place where those compulsions and restrictions give way to the happy life of a little girl gave her hope and solace. The mere thought of it seemed to sparkle. It didn’t matter how to reach that goal and the easiest way to achieve it was to jump out of the window.“

Without admitting it, this woman, who pictures herself holding a photo of her lover in her arms while jumping to her death (“maybe he would realize the truth then“) yearns for her natural self to be respected without having to meet the expectations of others all the time. She wants the people to understand what she really feels (and allow real feelings and emotions to develop first devoid of the pressure of conformity).

Marieluise Fleißer tells the story of the female protagonist’s failure in a world that doesn’t allow real communication between men and women because of rigid and senseless customs that mustn’t be questioned. These patriarchal habits systematically objectify women. The author’s highly subjective style reflects the main character’s psyche but still shows a straightforward and direct homeric quality. Thus, the reader can identify with her internal conflicts and mental struggles, which are insurmountable from her point of view. Consequently, the reading expe-rience is much more compelling and unsettling than an accurate reflection or convincing ex-planations of the ideological traps and vicious circles she is caught in would be. Reading the book today provides a lot of food for thought: In times of (supposed) equality, Tinder, Instagram, the #MeToo-movement and neo-liberal capitalist individual “freedom“, the competitiveness of which transcends all areas of human life: Have human relationships grown to be more mature than they were ninety years ago?