Artists: manuel arturo abreu, James Bantone, Jason Hirata, Deborah Joyce-Holman, Flora Leite, Gabriela Mureb, davi de jesus do nascimento, Yná Kabe Rodríguez Olfenza, Maya Quilolo, Sung Tieu, Wisrah C. V. da R. Celestino

Exhibition title: Cry Me A River

Invited by: Wisrah C. V. da R. Celestino

Venue: Simian, Copenhagen, Denmark

Date: Aug 26 – Oct 15, 2023

Photography: GRAYSC / All images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Simian, Copenhagen

Note: Exhibition’s booklet is available here

In the first part of The Object Relation, his fourth seminar, psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan introduces the imagery, the function, and the semiotics of a “hydro-electric factory in the middle of the current of a large river” to elaborate on a handful of concepts— among them and of particular interest here: reality and abstraction. Invested in demonstrating a need for a greater understanding of the relations between the symbolic and what we grasp as the physical realm, with the text, the author opens a space for reconsidering the semantic perception of things

A river can indeed be an object that affords countless allegories beyond its material composition and properties. It is a stream from which, although being a geographic feature, commonly enough instrumentality is offered for other-than-material narratives to be imagined. Yet, in the example given, Lacan focuses on how, on the contrary, the energy accumulated by the water flow through a power plant usually is defined by that solely.

In this debate, he intends to locate the point of analysis of an object such that it can touch a sort of abstract or, as he states, mythical notion of reality. A ground capable of trespassing signifiers like the station mentioned and, instead of ignoring them, negotiating with its emblems. Such symbolism, notably, does not coincide with fantasy. It (rather) acknowledges etymology, materiality, fiction, abstraction, and interpretation as components of reality. Within this territory, energy lies in capital, river, and work, as observed by Lacan, as much as in stillness, pause, silence, and laziness—like, for example, in the ontology introduced by Beyoncé in ENERGY (1).

CRY ME A RIVER brings to Simian a group of artists who, to address spirituality, violence, labor, and institutional critique, amplify the symbolism of objecthood with processes that invest in the sculptural potential of reinterpreting existing things. The exhibition includes works conceived in the last ten years by manuel arturo abreu, James Bantone, Jason Hirata, Deborah-Joyce Holman, Flora Leite, Gabriela Mureb, davi de jesus do nascimento, Yná Kabe Rodríguez Olfenza, Maya Quilolo, Sung Tieu, and Wisrah C. V. da R. Celestino.

The title of the show is borrowed from the homonymous song that, although composed and recorded by others before and after (2), was initially written to be sung by Ella Fitzgerald in 1955.

-Wisrah Villefort

[1] See ENERGY (2022) by Beyoncé. https:// genius.com/Beyonce- energy-lyrics

[2] Secondhand Songs lists 647 official recorded versions of Cry Me a River. https:// secondhandsongs. com/work/2158/ versions#nav-entity

Cry Me A River, 2023, exhibition view, Simian, Copenhagen

Wisrah Villefort, RENTAL/FATHER, 2023, One or more objects rented from the artist’s father, Variable materials and dimensions. Touching on movements such as conceptual art and institutional critique, yet questioning minimalism, Wisrah Villefort is deeply interested in investigating their agency and the lack of it within negotiations made with the agents that subsidize the existence of their work. While commenting on possession, property, and belongings, theory and practice are informed by the artist’s biography and experiences.

Wisrah Villefort, RENTAL/FATHER, 2023, One or more objects rented from the artist’s father, Variable materials and dimensions

Cry Me A River, 2023, exhibition view, Simian, Copenhagen

Gabriela Mureb, Machine #3: belt, 2013-2021, 0.75 hp electric motor, rubber belt, pulleys, inox clamps, galvanized steel shelving brackets, 40 × 140 × 30 cm. Machine #3: belt (2013-2021) is composed of a 0.75 hp, 1730 rpm electric motor, a rubber belt, and two pulleys with parallel axes. The motor, attached to one of the pulleys, starts the machine. The first movement of the engine, the rotation of its shaft, is transmitted to the pulley, which then pulls the belt, making it run at a speed of approximately 52.17 km/h, then moving the second pulley. The belt keeps spinning continuously in a loop around the pulleys. Every minute, the pulleys rotate 1730 times. The entire assembly measures approximately 40 × 140 × 30 cm. The most recent version of the work, now shown at Simian, was commissioned by the 5th New Museum Triennial.

Gabriela Mureb, Machine #3: belt, 2013-2021, 0.75 hp electric motor, rubber belt, pulleys, inox clamps, galvanized steel shelving brackets, 40 × 140 × 30 cm

Cry Me A River, 2023, exhibition view, Simian, Copenhagen

James Bantone, Chronic Oversharer, 2021, I S E custom made leather boots by Jazil Santschi, polyester thread, wood, zippers, acrylic, 80 × 30 × 44 cm each.

You know what? I don’t feel like being honest. And you know what’s fun? Being honest. What are you even talking about? Seriously, I’ve never met anyone else who thinks their own life is so fascinating. It’s exhausting. I mean, I wanted to fall asleep in my own vomit all day listening to you talk about how you bruise more easily than other people.

Are you for real? I am. Okay, well, people have been calling me self-centered since I was young, so it doesn’t really upset me anymore. You’ve got to come up with something more creative if you want to hit a nerve. Yeah,

it’s like it has no effect on you. And now it’s your turn. So we’re not avoiding our issues anymore? I actually wanted to do this at dinner.

Oh, my goodness. Can you just chill about dinner? That dish tasted terrible, and I want to erase it from my memory.

They have gone totally insane. Or maybe, just maybe, they’ve actually gone sane.

You all never listen to me. It’s like I’m invisible or something. Seriously, you have entire conversations right in front of me, like I’m not even there. And sometimes I wonder if my social anxiety is what’s holding me back from meeting people who would actually be right for me instead of a bunch of whiny nothings as friends.

Well, maybe they have a point. I mean, when was the last time we actually had any real fun together? It feels like it’s been ages.

That’s not true. Name one fun thing. This trip, if we had actually done anything I planned.

Oh, my goodness!

Hey, you know what? You should process what you just said. Because happiness is about appreciating what you have. Really? Is that some self-help nonsense? They go through a brief rehab stint, and we have to listen to all the nonsense they come up with.

You’re a cruel drunk, you know that? It’s crazy. Not to mention, you’re not even that intellectual.

Well, actually, they are. I’m going to stick up for them on this one. I’ve seen them read the newspaper on their phone. Then why, when I’m around them, do I feel like my brain is going to atrophy? I mean, seriously, they can be a little unstimulating.

“Unstimulating”? Are we in some period drama? Do I really want to be like you? Mentally unstable and miserable?

Whoa, whoa, whoa. When did we start with all of this name-calling? We didn’t start with the name-calling. They started with the name-calling. Um, I did not start with the name-calling. I started with your ridiculous idea of honesty, miss tan legs. I’ve never talked to you that way.

You know what? You are tortured by self- doubt and fear, and it is not pleasant to be around.

That’s really mean. It is mean. It’s really mean, what you just said. I’m sorry my heart was broken after that breakup. Well, we would have no way of knowing that because the only issues you ever talk about are your issues with me.

Seriously, we’ve known each other for a long time. I’ve been on this planet for a while,

and I’m not showing any signs of changing. Look, all you’ve ever done is talk about the fact that you are changing, that you want to change, self-improvement, all that stuff. So I get on board with it and what do you do? You disappoint me. That’s all you’ve done for the past couple of years.

Well, then maybe you should lower your expectations. I can’t lower them any further. Maybe you should try what I do. I don’t expect anything from any of you.

I’m so sick of all of you.

Cry Me A River, 2023, exhibition view, Simian, Copenhagen

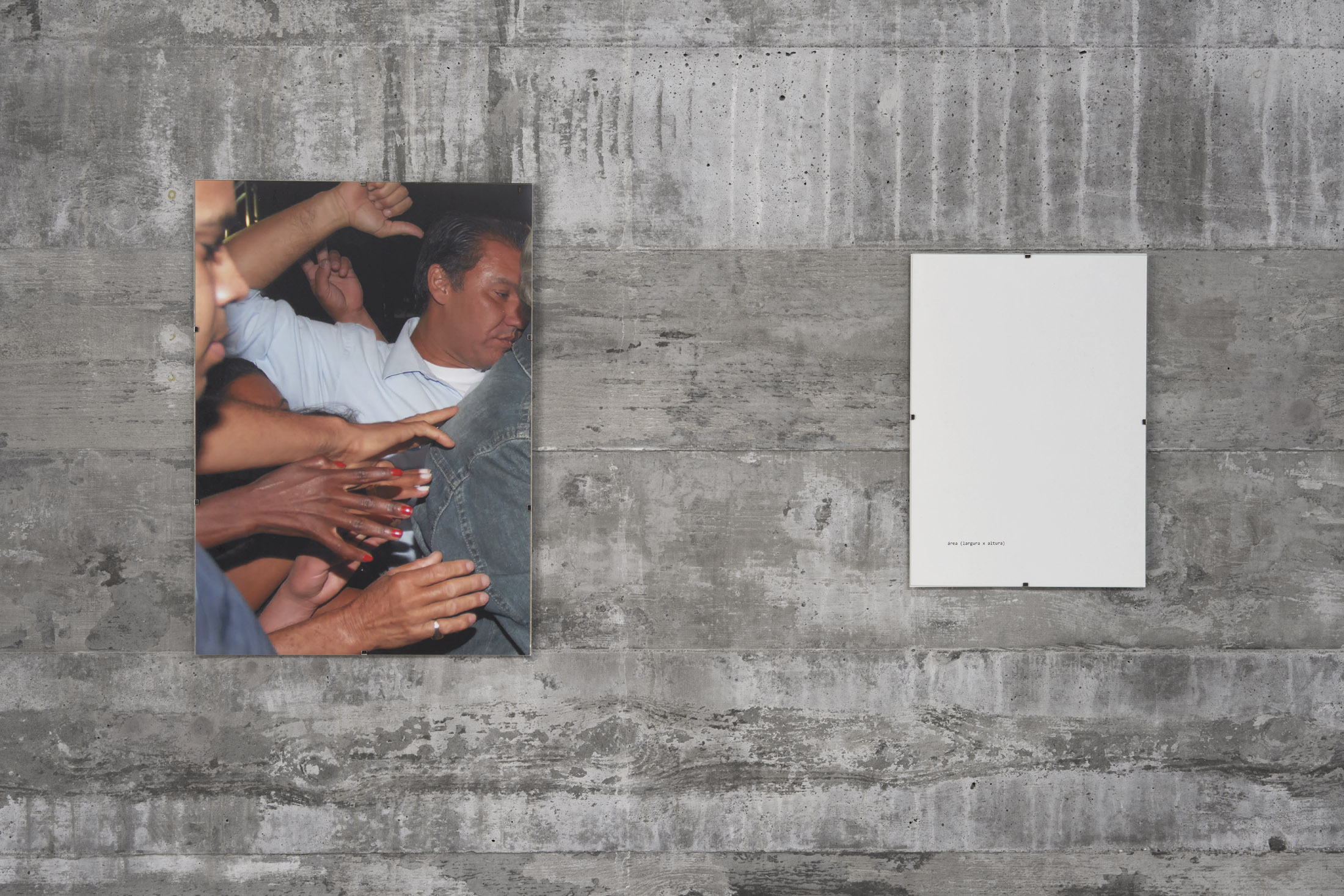

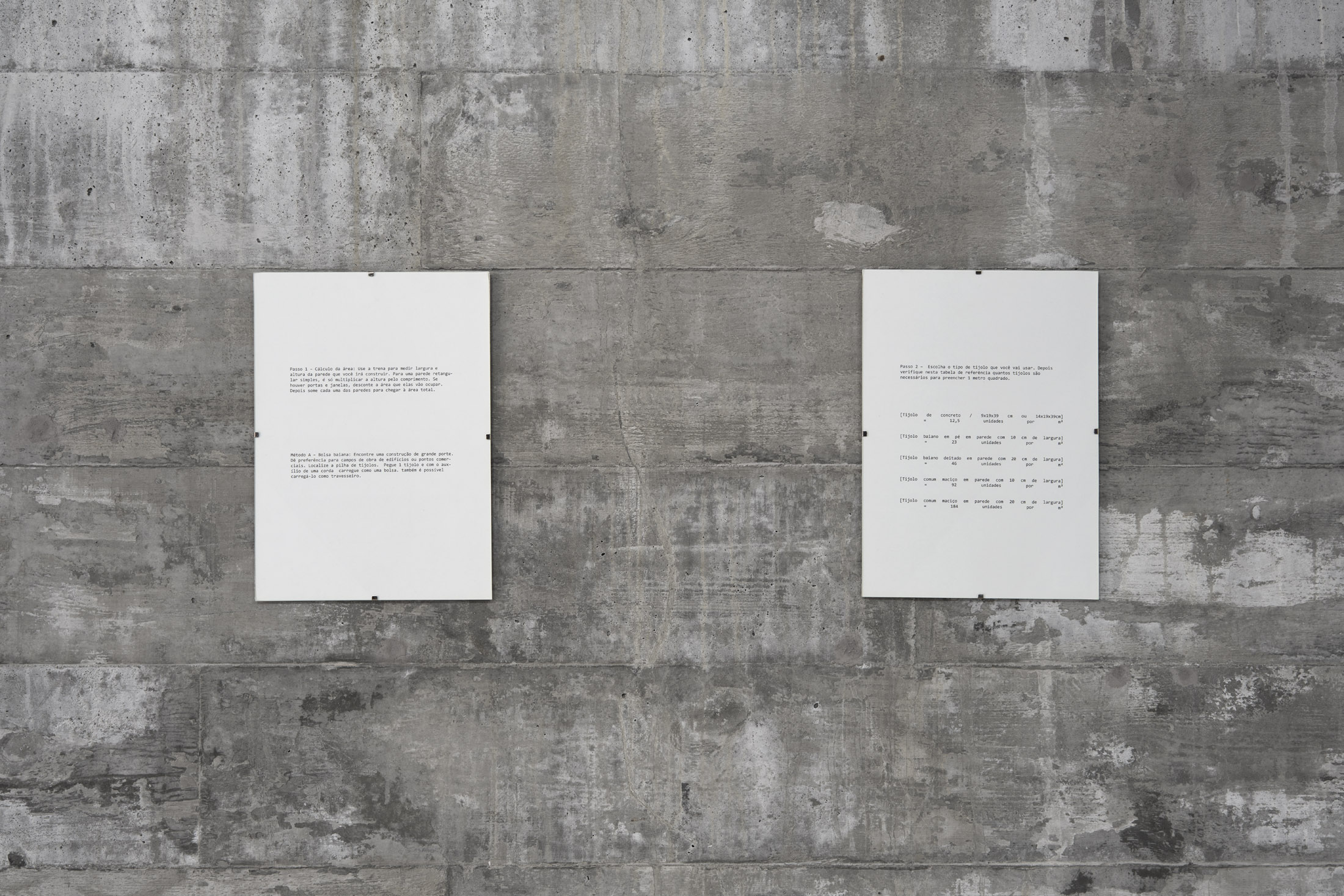

Yná Kabe Rodríguez Olfenza, Uma construção (Ou faltam paredes na casa das pariceiras), 2017, Variable materials and dimensions.

(Pipe) https://youtu.be/t5COc-wY1IE

(Page one)

Found photography

(Page two)

Area (width × height)

(Page three)

Step 1 – Area Calculation: Use a measuring tape to find the width and height of the wall you will build. For a simple rectangular wall home, just multiply the height by the length. If there are doors and windows, deduct the area they will occupy. Finally, add up each of the walls to get the total area.

Method A – Bolsa Bahia: Find a large building. Give preference to construction sites for buildings or commercial points. Identify the pile of bricks. Take one brick and carry it like a bag with the help of a cord. It is also possible to bring it as a pillow.

(Page four)

Step 2 – Choose the type of brick you are going to use. After, check in this reference table how many bricks are needed to fill one square meter.

[Concrete brick / 9 × 19 × 39 cm or 14 × 19 × 39cm]

= 12.5 units per m2

[Baiano brick standing on a 10 cm wide wall]

= 23 units per m2

[Baiano brick lying on a 20 cm wide wall]

= 46 units per m2

[Common solid brick wall, 10 cm wide]

= 92 units per m2

[Common solid brick wall, 20 cm wide]

= 184 units per m2

(Page five)

Method B – Platform Jump: To carry two bricks from the construction site for the land you want to build your home, use a strip of synthetic leather or other fabric and tie two bricks to each foot. Take the path firmly, with patience and caution.

(Page six)

A civilian (from the Latin civilis, genitive of civils, “citizen”), as of under the International Humanitarian Law, is a person who does not belong to the armed forces of their country

Yná Kabe Rodríguez Olfenza, Uma construção (Ou faltam paredes na casa das pariceiras), 2017, Detail, Variable materials and dimensions

Yná Kabe Rodríguez Olfenza, Uma construção (Ou faltam paredes na casa das pariceiras), 2017, Detail, Variable materials and dimensions

Yná Kabe Rodríguez Olfenza, Uma construção (Ou faltam paredes na casa das pariceiras), 2017, Detail, Variable materials and dimensions

Yná Kabe Rodríguez Olfenza, Uma construção (Ou faltam paredes na casa das pariceiras), 2017, Detail, Variable materials and dimensions

Cry Me A River, 2023, exhibition view, Simian, Copenhagen

davi de jesus do nascimento, colher de colher fumo e esgarçar piaba fresca ou cajado de caboclo d’água, 2023 Oar shovel, flood wood patching heron’s neck, 86 × 29 × 4 cm.

From the “águas guardadas” series.

The work births from the stick of a heron with the remains of an oar. The objects from the series “guarded waters” destroy themselves by their gathering in ravines, riverbanks, or water backyards. Pieces of watercraft, wooden bones, piranha, and saruê fossils compose the attempt at a presépio: vestiges of old fruits, green nets, and canoe dogs.

When I was born, in 1997, in the blaze of the northern region of Minas Gerais, Brazil – they baptized me with my father’s name: Davi de Jesus do Nascimento. I’m a curimatá riverside artist, a supporter of agglomerations, and an on-the-cuff writer. Conceived at the margins of the São Francisco river—the waterway of my life—I work collecting affections from the riverside ancestry and realize “almost-rivers” in the arid. I was raised alongside carranqueiros fishermen and washerwomen. The weight of carrying the river on my back drinks from the source of the first suns I cried in my life. To hold on to the humpback, the carranca has made me feel the power of the wind of my bent taboca on the tracing of the loose kite that went down the gongo-like snail envelopment spiral to the right heel as a snake, bait, fish, and rock.

manuel arturo abreu, mamajuana, 2021, Sacred roots, rum, red wine, honey, glass, saran wrap. Variable dimensions.

One of the first distilled spirits in the Americas, mamajuana is a Dominican spiced alcoholic infusion of rum, red wine, and honey with tree bark and herbs. The taste is similar to port wine and the color is a deep red. Dominicans describe its effects as medicinal, aphrodisiac, and more. The indigenous Arawak-speaking tribe among the First Peoples of Ayiti originally prepared a tea from the specific herbs that make up mamajuana; post-Columbian mixed islanders added alcohol to the recipe. During the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo, the sale of mamajuana was prohibited, except for those with a medical license.

Mamajuana was popularized as a local herbal medicine and aphrodisiac in the 1950s by Jesus Rodriguez, a native of San Juan de la Maguana. Materials for the brew differ regionally, but some common species include: Anamú (Petiveria alliacea), Anis estrellado (star anise, Illicium verum), Bohuco pega-palo (Cissus verticillata), Albahaca (basil, Ocimum basilicum), Canelilla (Cinnamodendron ekmanii), Bojuco caro (princess vine), Marabeli (Securidaca virgata), Clavo dulce (whole clove), Maguey (Agave spp.), and Timacle (Chiococca alba).

manuel arturo abreu, mamajuana, 2021, Sacred roots, rum, red wine, honey, glass, saran wrap. Variable dimensions

manuel arturo abreu, mamajuana, 2021, Sacred roots, rum, red wine, honey, glass, saran wrap. Variable dimensions

Cry Me A River, 2023, exhibition view, Simian, Copenhagen

Cry Me A River, 2023, exhibition view, Simian, Copenhagen

Sung Tieu, What Do You Let Go?, 2021, Plastic flower, polished and unpolished stainless steel. 66 × 48 × 5 cm.

Tieu’s work takes place at the intersection of her personal experiences, global history, and the cultural incursions of European art traditions. Her immersive installations result from her research of the dynamics of hegemonic globalized capitalism, working through and with spatial dislocation while paying heed to the cultural testimony of the Vietnamese diaspora communities in Germany. Through the personal lens of post- colonial identity and cultural membership, she upsets the status of objective narrative and of proof when science works at the service of sociopolitical agendas. While addressing social and cultural class divides in both contemporaneity and recent history, Tieu’s work foregrounds the ways in which evidence is manipulated in imperialist violence both of physical and psychological nature

Jason Hirata, Painted Square, 2021, Wall painting, Executed by Toke Flyvholm and Markus von Platen, Environmental dimensions.

Painted Square consists of a pictorial intervention which alters the proportions of a surface, bringing it to a square. The position and the color of the work are the result of a negotiation with its commissioner.

The piece was conceived at Fanta-MLN as a permanent installation on the floor that exceeded the temporary nature of the artist’s exhibition From Now in Then (2021). Similarly to the other works in the show mentioned, the piece considers the space-time structures that constitute the experience of a work and an exhibition, trying to expand them through a reflection on the conditions that precede and follow their manifestation in a space

Flora Leite, Reconciliation, 2014, Shell, water, basin and main components of sea water diluted in proportions equivalent to marine average (magnesium sulfate, potassium chloride, calcium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, sodium chloride), 10 × 40 × 40 cm.

Reconciliation derives from a desire to accommodate nature within culture, commerce, and daily life. Through salts and other products bought in supermarkets and pharmacies, the work chemically mimes seawater, creating an allegedly ideal habitat for a seashell. The supposedly natural element of the work, the seashell, is dead—in fact, more a fossil than an animal, of which the missing mussel is its mold— and many of its kind are also available to be bought from souvenir shops in any country with a coastline. A type of do-it-yourself conchology is especially endeared by those whose kitschy taste can be traced back to the Victorian-Era aquarium mania of the 19th century, to the conchylomania of the 17th century, to curiosity cabinets of the Renaissance—which birthed museums themselves. Seashells also structure the indecipherable Sambaquis of the Brazilian Southern coastline; a peculiar array may decorate our grandmothers’ homemade picture frames; some are even kept inside mason jars, usually collected on a trip full of walks on the beach. The seashell—or rather, its usage within stuff and amidst our things— reminds us that throughout the history of our objects, some part of nature has become kitsch in itself

Deborah-Joyce Holman Thicc and Slippery, 2020, Ink on human teeth, wire, aluminum, mirror, 7 × 7 × 7 cm.

With Thicc and Slippery, 2020, the artist explores biological matter as hard evidence while shedding light on the anachronism of DNA and other parameters it carries, such as the determination of gender assigned at birth or geographical origin of an individual, while reality in its unpredictability constantly trips them. By writing words in ink on teeth from their friends, Holman alludes to the dimension of teeth as a signifier, a linguistic code. They play on the ambivalence of this organic medium that can both communicate and conceal meaning, opening possible readings which are not limited to their genetic contents.

This reflection is nurtured by a long legacy of teeth being used as social signifiers in many cultures across the world for centuries: from the Mayans who replaced them with jade stones to the contemporary grillz. By intervening directly on teeth, the artist questions the way in which identity is read, in a poetic attempt at making sure our bones retain some of our agency once we have long passed away. With this work, Holman explores, in particular, the intersections of queerness (and its suggested mobility) and Blackness (and associated immobility) in the European context.

(Text by Caroline Honorien, 2021)

Cry Me A River, 2023, exhibition view, Simian, Copenhagen

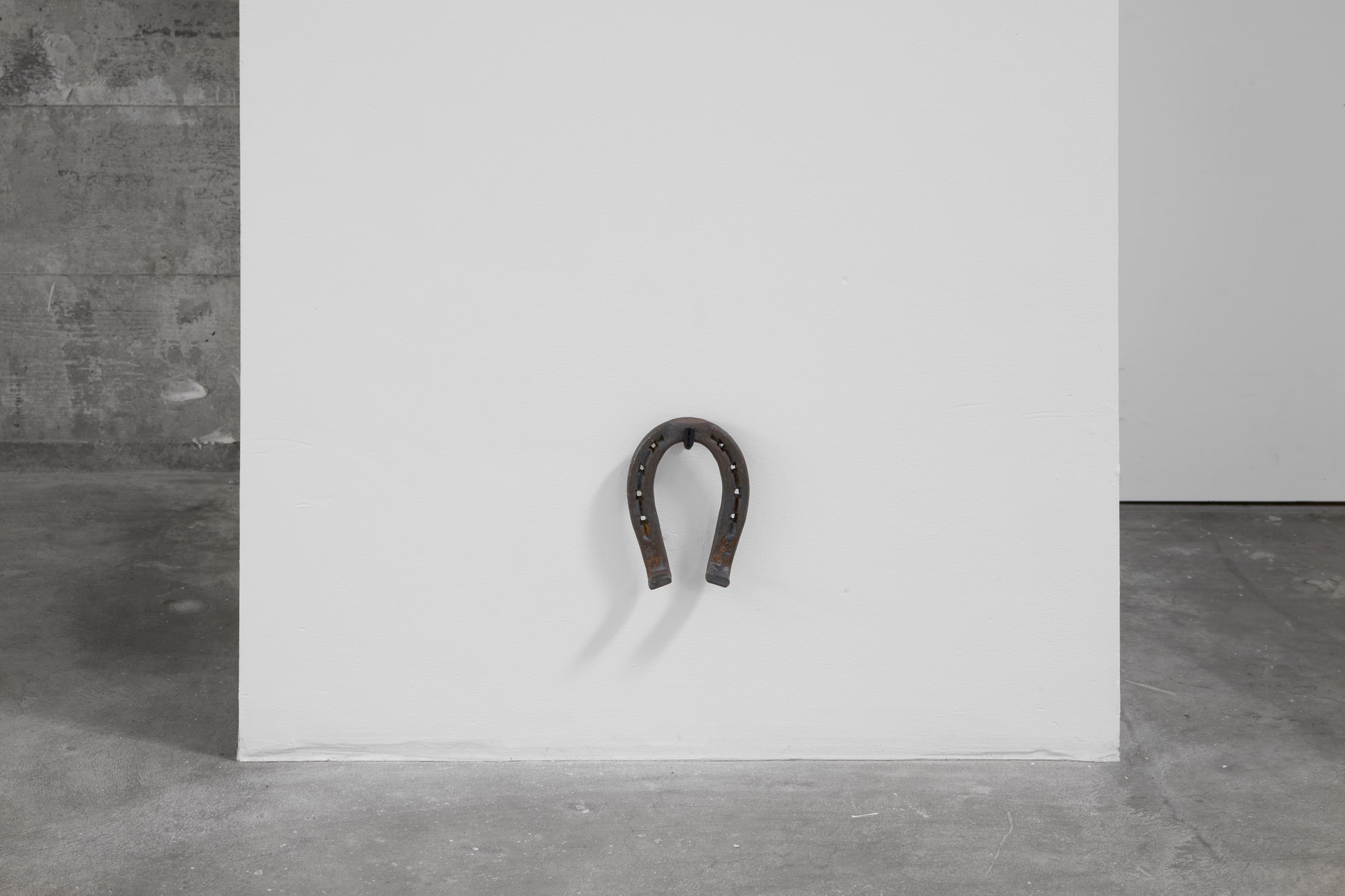

Maya Quilolo, SORTE, 2023, One horseshoe used by an animal hung alongside each doorway, Variable materials and dimensions.

In a river bend, luck and bad luck cross the head passage. Those who cross the bridge used to know the secret of the river that flows both ways. Is the exhibition space a mandinga field?

Maya Quilolo, SORTE, 2023, One horseshoe used by an animal hung alongside each doorway, Variable materials and dimensions

Maya Quilolo, SORTE, 2023, One horseshoe used by an animal hung alongside each doorway, Variable materials and dimensions

Gabriela Mureb, Machine #3: belt, 2013-20210, 75 hp electric motor, rubber belt, pulleys, inox clamps, galvanized steel shelving brackets, 40 × 140 × 30 cm