Artist: Caroline Bachmann

Exhibition title: 58 av. J.-C.

Venue: Kunsthaus Glarus, Glarus, Switzerland

Date: March 15 – August 23, 2020

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Kunsthaus Glarus

Judith Welter

History

The panorama of the Jura between the Rhine and Rhone extends over ten canvases. 58. av. J.-C. (2020), a historical painting devoid of people. Twelve fires are a testament to the civilization of Switzerland’s distant history: they represent the twelve cities set ablaze by the Helvetians. Julius Caesar describes this in De bello gallico, his accounting of the Gallic Wars, which started in the same year. The past is an invention. Caroline Bachmann references Caesar’s literary vision, between fact and fiction, projecting the fires of the Helvetians’ burning cities—according to this account they burned their settlements before the exodus to the west—onto a vast landscape situated before a ridge of hills. Based on a meticulous study of topology and lighting conditions, the artist has created a panorama depicting today’s Swiss border. The glow of the sunset indicates the Battle of Bibracte, which led to the defeat of the Helvetians by Caesar. Caroline Bachmann’s paintings often reference the geographical and historical context of her immediate surrounds. In her work, (art) historiography always takes on a conceptual significance. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, women were considered physically unsuitable for mastering the highest of all genres, historical painting. The paintings had to be monumental in order to unite invention and facts in a credible way; painting therefore required a feat of physical strength reserved primarily for male artists. 58. av. J.-C. takes up the impressive dimension of the panorama without being overpowering. Exhibition viewers populate the deserted historical painting, returning it to the context in which it was created: the present. Without the title that provides the date, we might read it today as a dystopian scene of a post-apocalyptic future.

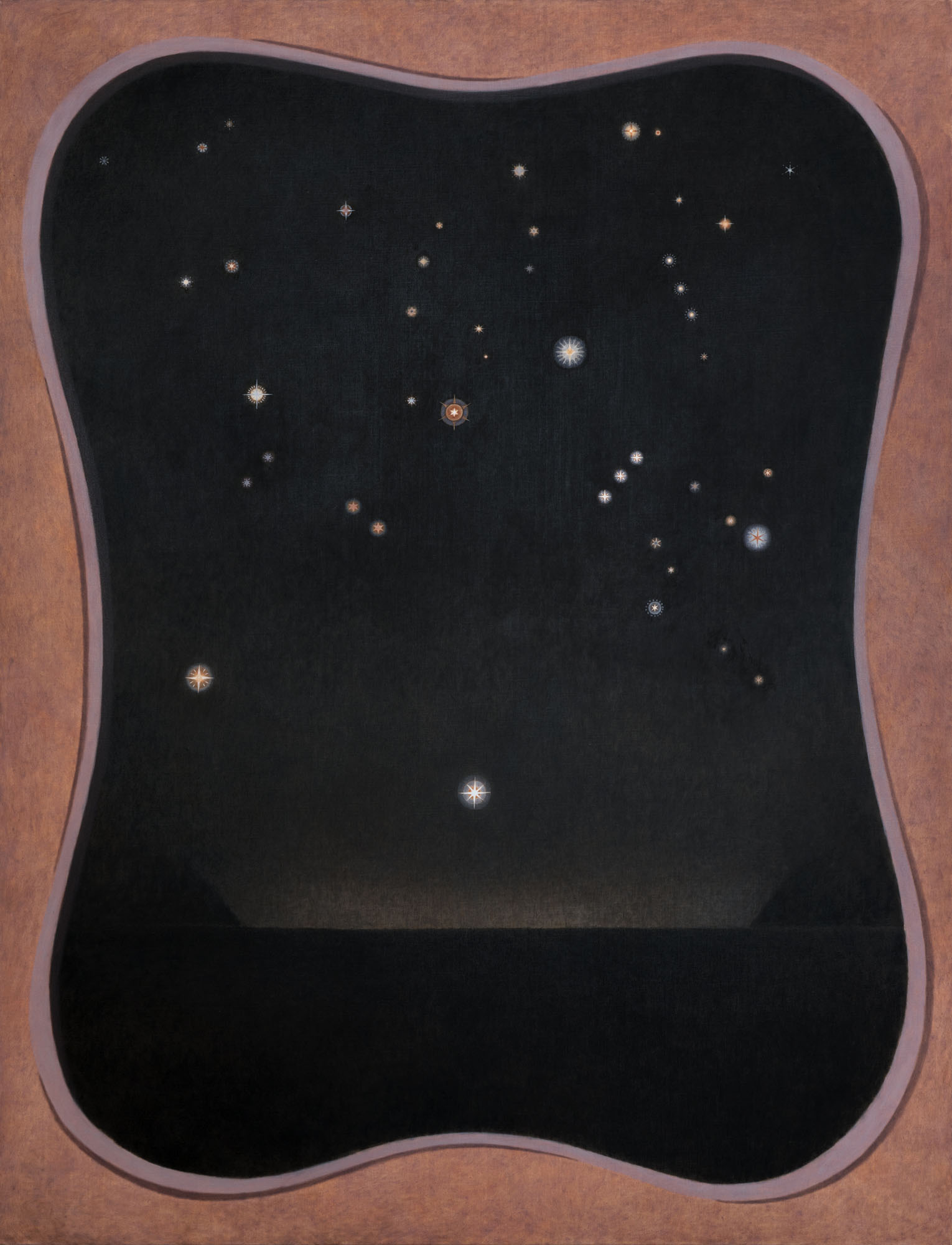

Landscapes

The present as a temporal and conceptual element is also central to other Caroline Bachmann landscapes. The titles of the works describe the themes depicted: Double arc-en-ciel (2019)—a double rainbow on the horizon of Lake Geneva. Lever de soleil nuages gris (2019), a sunrise shrouded in gray clouds. They all deal with the same subject: the panorama of Cully, where the artist lives and works; the view of Lake Geneva and the Rhone Valley on the opposite side, over which towering mountains rise. At night and early in the morning—it is still dark or the sun is about to rise—Caroline Bachmann observes the weather and lighting conditions. Always following the same procedure, the artist captures her specific view of the landscape, the lake and the mountains in the form of a pencil sketch. During her observations, she pays attention to the lighting and weather conditions as well as all elements visible from her vantage point: clouds, fog, the moon, and waves as if they were characters in a scene. In the studio, Caroline Bachmann paints the settings relying on the sketches and her memories of the mood. The act of contemplation, a topos of plein air painting as well as painting’s history of reception, leads to a kind of standardized exercise in viewing. Later this is transferred into landscape views in a similarly standardized and meditative process—creating oil paintings takes time and patience. Caroline Bachmann’s work is not just about seeing and perceiving. Images have a social, narrative, and political function that resonates continuously. Despite a clear reference to a history of landscape painting, beginning with artists who traveled through the Swiss Alps in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in order to create various views of the Alps and the weather, up to the symbolistic (dream) landscapes of the twentieth century, it would be too simplistic to view Caroline Bachmann’s paintings as a continuation of this art-historical lineage. A lineage, by the way, which has left clear traces on the Glarner Kunstverein collection, which for a long time was characterized by popular and generally backward-looking landscape motifs. Over one hundred years before the Glarner Kunstverein’s founding in 1870, Zurich artist Conrad Meyer was purportedly one of the first to reproduce the Swiss Alps in large-format panoramas and detailed views of the Klöntal landscape. What’s seductive about Caroline Bachmann’s landscapes is that they are also based on similar generic and at times cliched notions of nature that have been made into art under various pretexts in history, in addition to their emphasizing of an already mediated, digitized image of landscape. Capturing a significant mood or instant is experiencing a renaissance not only in art today but also in everyday life as a supposedly unique, i.e. “authentic” image-product created without filters for social distinction and distribution. Caroline Bachmann’s painted frames, which border the image on canvas—this is also an art historical quoting of the work of the American painter Louis Michel Eilshemius—illustrate how we see today: by means of a standardized, albeit free “frame,” depending on the medium. The edges of the screen, of the interface, the framed viewfinder of the digital camera, the elegant black edge of the mobile phone, the image and its technology are seamlessly fused; or even our view of the landscape through the train, plane, or car window. This technologized and constantly shared seeing and collecting of landscapes and moods as well as their utilization—imagery under the auspices of acceleration—stand in contrast to Caroline Bachmann’s paintings, for instance, in the meditative and slow nature of their creation. These are mysterious images that demand a physical presence, capture time, and at the same time elude all temporality. Caroline Bachmann’s works are nourished by generic notions of landscape as well as characterized by individual and personal experience.

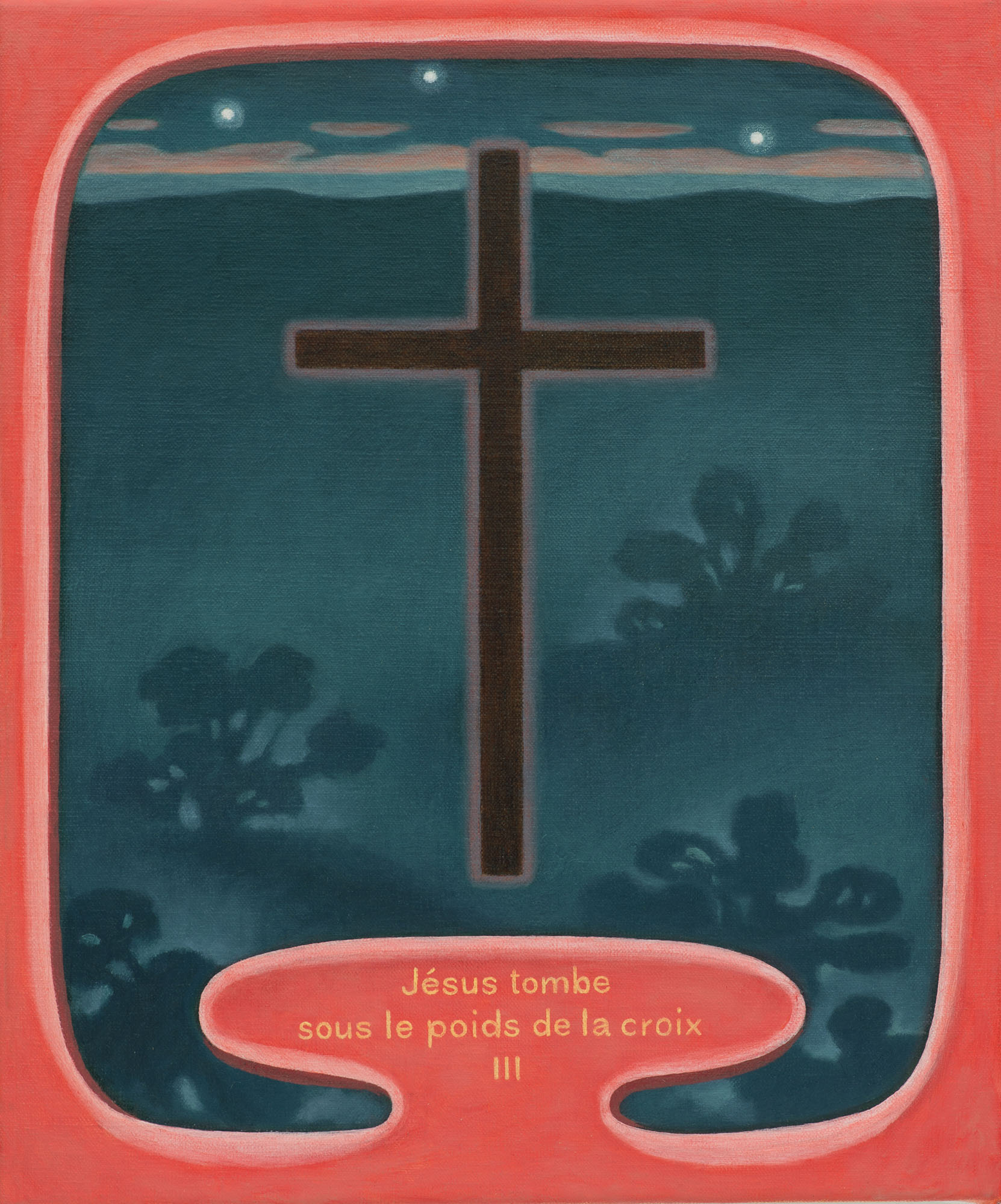

Stations of the Cross

Similar to historical paintings devoid of human protagonists, Caroline Bachmann’s Chemin de croix (2018) does entirely without figures. Rather than a typical account of the Stations of the Cross, which, in the Catholic tradition, tells the history of Jesus from his condemnation to his interment, scenic and daytime lighting and color moods are employed here to create a narrative. The fourteen small-format paintings are all based on the same formal framework: a monumental cross in the center of the image and an associated original text in an identical frame. The stations mark the transition from deep night to day, from the highest point of the sun to its lowest—atmospheres familiar to us from long hiking days beginning before sunrise. Colors cannot yet be made out in the twilight. Similar to the reverent, ritualistic walking associated with the Stations of the Cross, Caroline Bachmann’s repetitive experimentation with various painting genres has a potentially therapeutic character: the mastery of the genres and associated practice is equally a precise and clear, as well as intellectual, practically scientific, but also physical activity. Caroline Bachmann’s Chemin de croix is also about visualization: the beginning of the peregrination (here the first of the Stations of the Cross) is at night. Without recognizing anything, we set out on our way into the landscape, but also into the day. With intensifying light, the ever-brightening landscape increasingly separates itself from its horizon. The horizon also becomes a figure that leads through the narrative: while the image is directed only towards the earth at the beginning, the cycle ends in heaven. The horizon line moves lower and lower towards the bottom of the image to the benefit of the ever-burgeoning sky. Placed front and center, the cross plays with the economy of attention in the image, while the text serves to remind one of the narrative.

Flowers

Naturalness and artificiality intersect in the typology of the still life. The flower still life occupies a special place within this genre. It is ascribed a decorative, edifying significance. The true-to-nature level of accuracy demanded of it is nevertheless always a form of painting about the historical function of painting and its complex task of imitating nature. As a sublime motif of transience, but with domestic and profane attributes, the flower still life is not least linked to gender-specific role models in painting. Caroline Bachmann’s white flowers seem strangely lifeless, as if interested in exaggerating their function as a vanitas motif. They are not unlike a painting in the collection of the Glarner Kunstverein created by the painter Ottilie Roederstein (1859–1937), the first female artist to be included in the collection and who is currently being “rediscovered.” In addition to two portraits—the commissioners were also the donors—the Glarner Kunstverein is in possession of a small flower still life, a gift in gratitude for a stay with her patrons.

Portraits

In historical portrait galleries, the important historical actors are mainly men. Caroline Bachmann has been working on a cycle of portraits of women for several years. All of them are artists from Caroline Bachmann’s immediate surrounds. The frontal portraits depict the persons before scenic, ornamental backgrounds. They are both personal and general in nature. The portrait demonstrates how every painting is also an invention, a subjective view of the individual. It is projection, vision, a point of view.

Caroline Bachmann’s paintings oppose a rigid hierarchy of genres in painting that is bound not least to gender images, without didactically dismantling them. Rather, the categories serve as models, as adopted classifications: religious images, portraits, still lifes, landscapes; a keyboard leading away from the conceptual image in her earlier works.

Caroline Bachmann, Lever de soleil nuages gris, 2019, oil on canvas, 80 x 80 cm. Photo: Gunnar Meier

Caroline Bachmann, 58 av. J.-C., 2020, installation view. Photo: Gunnar Meier

Caroline Bachmann, 58 av. J.-C., 2020, installation view. Photo: Gunnar Meier

Caroline Bachmann, 58 av. J.-C., 2020, installation view. Percée ciel bleu, 2019, oil on canvas, 30 x 24 cm / Lac vert et nuages gris, 2017, oil on canvas, 30 x 24 cm / Vague grise, 2018, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 cm. Photo: Gunnar Meier

Caroline Bachmann, 58 av. J.-C., 2020, oil on canvas, 10 parts each 80 x 80 cm. Photo: Gunnar Meier

Caroline Bachmann, 58 av. J.-C., 2020, installation view. Marie José Burki, 2017, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 cm / Emilie Ding, 2019, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 cm / Vidya Gastaldon, 2015, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 cm. Photo: Gunnar Meier

Caroline Bachmann, Pleine lune lac jaune, 2016, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 cm. Photo: Gunnar Meier

Caroline Bachmann, 58 av. J.-C., 2020, installation view. Chemin de Croix I, 2018, oil on canvas, 40 x 33 cm / Ciel étoilé I, 2019, oil on canvas, 170 x 130 cm. Photo: Gunnar Meier

Caroline Bachmann, 58 av. J.-C., 2020, installation view. Chemin de Croix V–I, 2018, oil on canvas, je 40 x 33. Photo: Gunnar Meier

Caroline Bachmann, 58 av. J.-C., 2020, installation view. Chemin de Croix XII–III, 2018, oil on canvas, je 40 x 33. Photo: Gunnar Meier

Caroline Bachmann, 58 av. J.-C., 2020, installation view. Photo: Gunnar Meier

Caroline Bachmann, 58 av. J.-C., 2020, installation view. Photo: Gunnar Meier

Caroline Bachmann, 58 av. J.-C., 2020, installation view. Photo: Gunnar Meier

Caroline Bachmann, Reflet nuages noirs, 2019, oil on canvas, 80 x 80 cm / Loupe, 2018, oil on canvas, 80 x 80 cm. Photo: Gunnar Meier

Caroline Bachmann, Double arc-en-ciel, 2019, oil on canvas, 170 x 130 cm / Vent d’ouest, 2016, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 cm / Lune vaudère avec cadre, 2015, oil on canvas, 80 x 80 cm / Bise avec nuages roses et noirs, 2017, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 cm. Photo: Gunnar Meier

Caroline Bachmann, Tulipe perroquet, 2018, Öl auf Holz, 40 x 30 cm / Iris blanc, 2019, Öl auf Holz, 40 x 30 cm / Camelia blanc, 2017, Öl auf Holz, 40 x 30 cm / Ciel étoilé I, 2019, oil on canvas, 170 x 130 cm. Photo: Gunnar Meier

Caroline Bachmann, Lever de lune, 2017, Öl auf Holz, 40 x 30 cm / Lune halo orange avec cadre, 2018, oil on canvas, 80 x 80 cm / Lune reflets bleus avec cadre, 2015, oil on canvas, 80 x 80 cm. Photo: Gunnar Meier

Caroline Bachmann, Lac vert et nuages gris, 2017, oil on canvas, 30 x 24 cm

Caroline Bachmann, Ciel étoilé II, 2019, oil on canvas, 30 x 24 cm

Caroline Bachmann, Chemin de Croix I, aus Chemin de Croix, 2018, oil on canvas, 40 x 33

Caroline Bachmann, Chemin de Croix III, aus Chemin de Croix, 2018, oil on canvas, 40 x 33

Caroline Bachmann, Chemin de Croix XIV, aus Chemin de Croix, 2018, oil on canvas, 40 x 33

Caroline Bachmann, Loupe, 2018, oil on canvas, 80 x 80 cm

Caroline Bachmann, Double arc-en-ciel, 2019, oil on canvas, 170 x 130 cm

Caroline Bachmann, Lune vaudère avec cadre, 2015, oil on canvas, 80 x 80 cm

Caroline Bachmann, Bise avec nuages roses et noirs, 2017, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 cm

Caroline Bachmann, Iris blanc, 2019, oil on wood, 40 x 30 cm

Caroline Bachmann, Lune halo orange avec cadre, 2018, oil on canvas, 80 x 80 cm