I’ve found it useful to approach this exhibition with a negotiation between two similar terms: restraints and constraints. In some online course notes for a molecular physics class at the University of Oregon, I found:

“The seminal difference between a constraint and a restraint is that a constraint is an absolute restriction imposed on the calculation, while a restraint is an energetic bias that tends to force the calculation toward a certain restriction.”

In a way all painting could be said to deal with the absolute restrictions of static figures caught in oxidizing pigmented oil or acrylic emulsion. But Bailly-Borg’s figures in this exhibition do not seem to lament their confinement– struggling to escape their restraining substrates– so much as they seem to ecstatically writhe within their confined quarters. Oftentimes under restraint, one writhes all the more ecstatically. But to say that Carlotta’s reproductions in pencil are writhing in expressive intensity might not be the most accurate of characterizations.

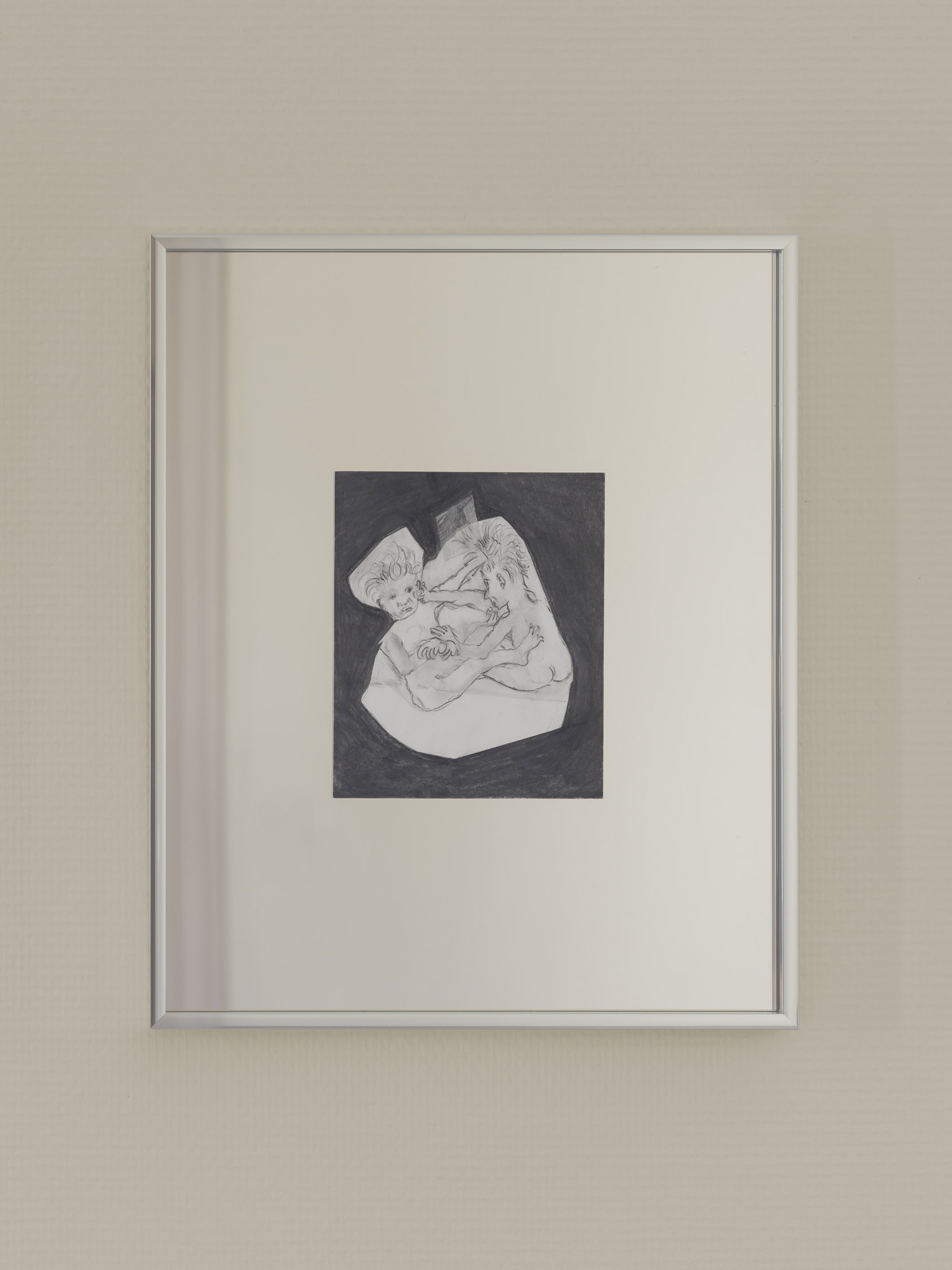

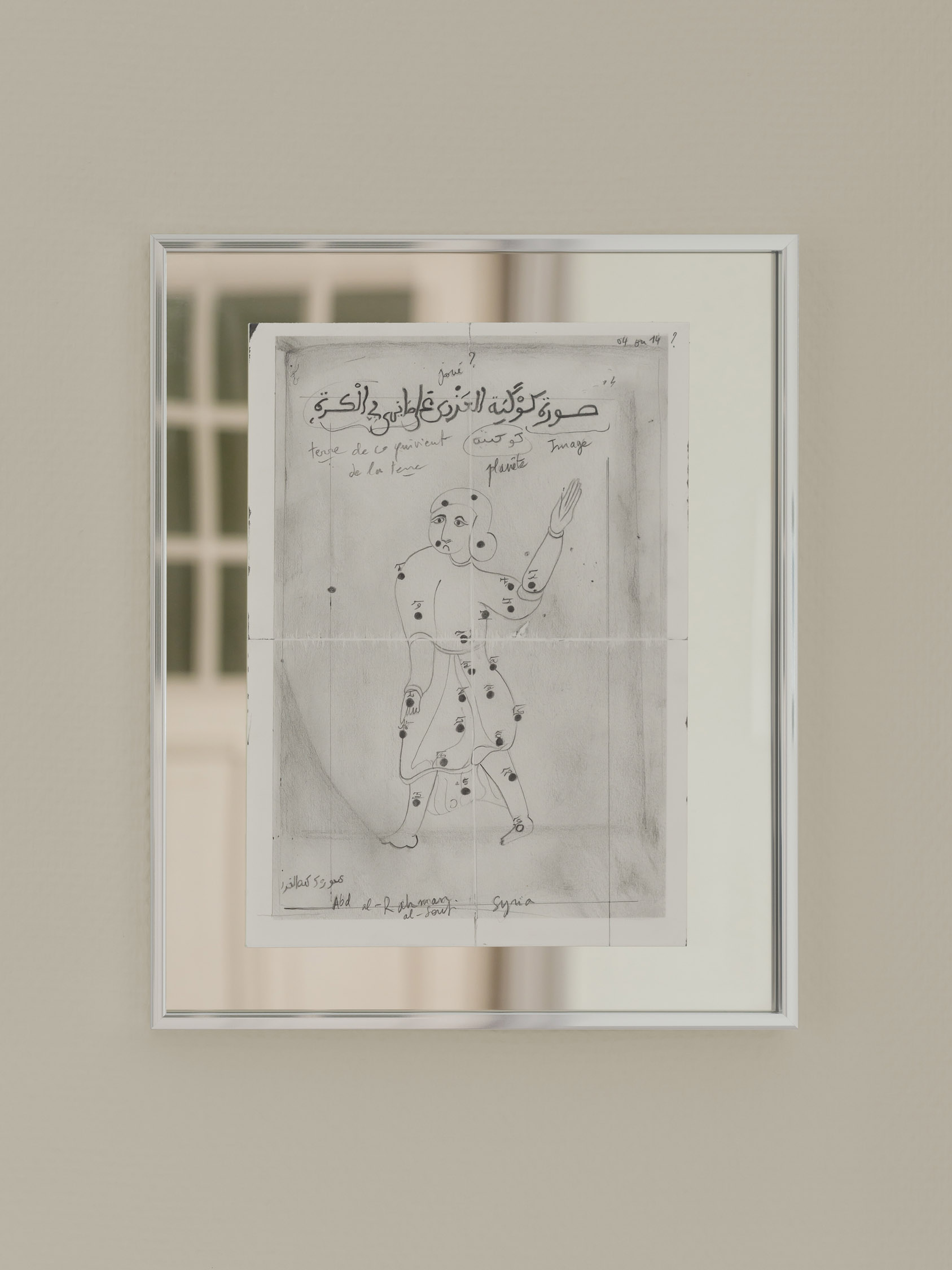

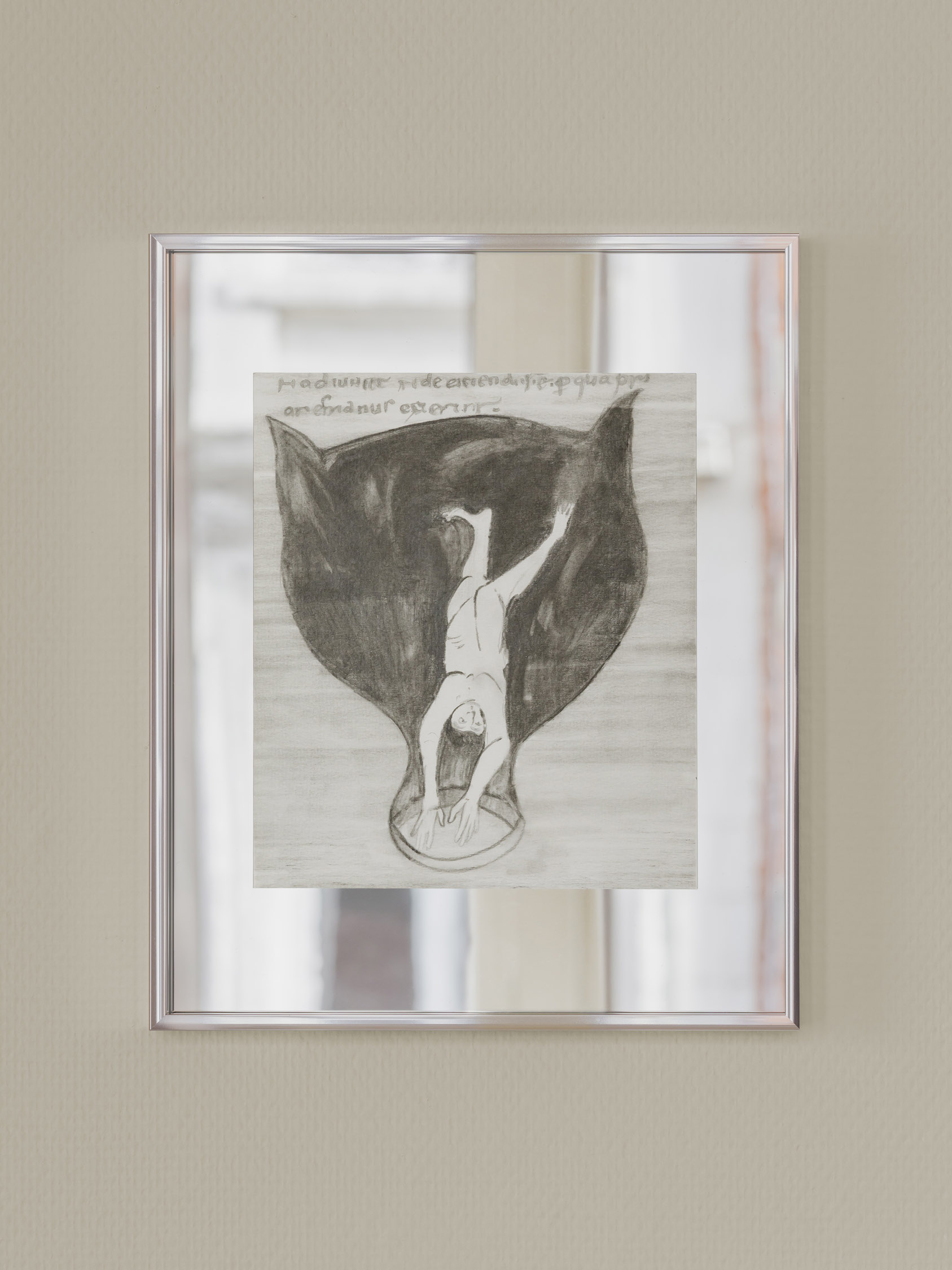

And so in Bel Étage the artist offers us two castes: the first being the painted and sandblasted figures which seem to adapt to their given contours, their imposed restraints; and the second being the 7 mirror-framed renderings in pencil, each constrained to a reproduction from an eclectic array of original sources. There is a Breugel; there is a drawing found by the artist on the street; there is a diagram taken from a 10th century book of astronomy from the Abbasid Empire; there is an image of taxidermied yogic frogs; there are others. It goes without saying that Carlotta is skilled with a pencil and an eraser, yet it is precisely these images’ emphasis on mimetic accuracy that seems to diminish the relevance of any formalist critique. In fact, the simple strangeness of their mirror frames has an effect which likens these works to footnotes or references. Here I think of a more historical version of Joselit’s “network painting,” one that substitutes the representation of a social sphere of influences for a constellation of genealogies. However, it would be neither fair to the artist nor the exhibition’s visitors to see this show through the pictorial frame of a moodboard, a sampling of sources of aesthetic inspiration.

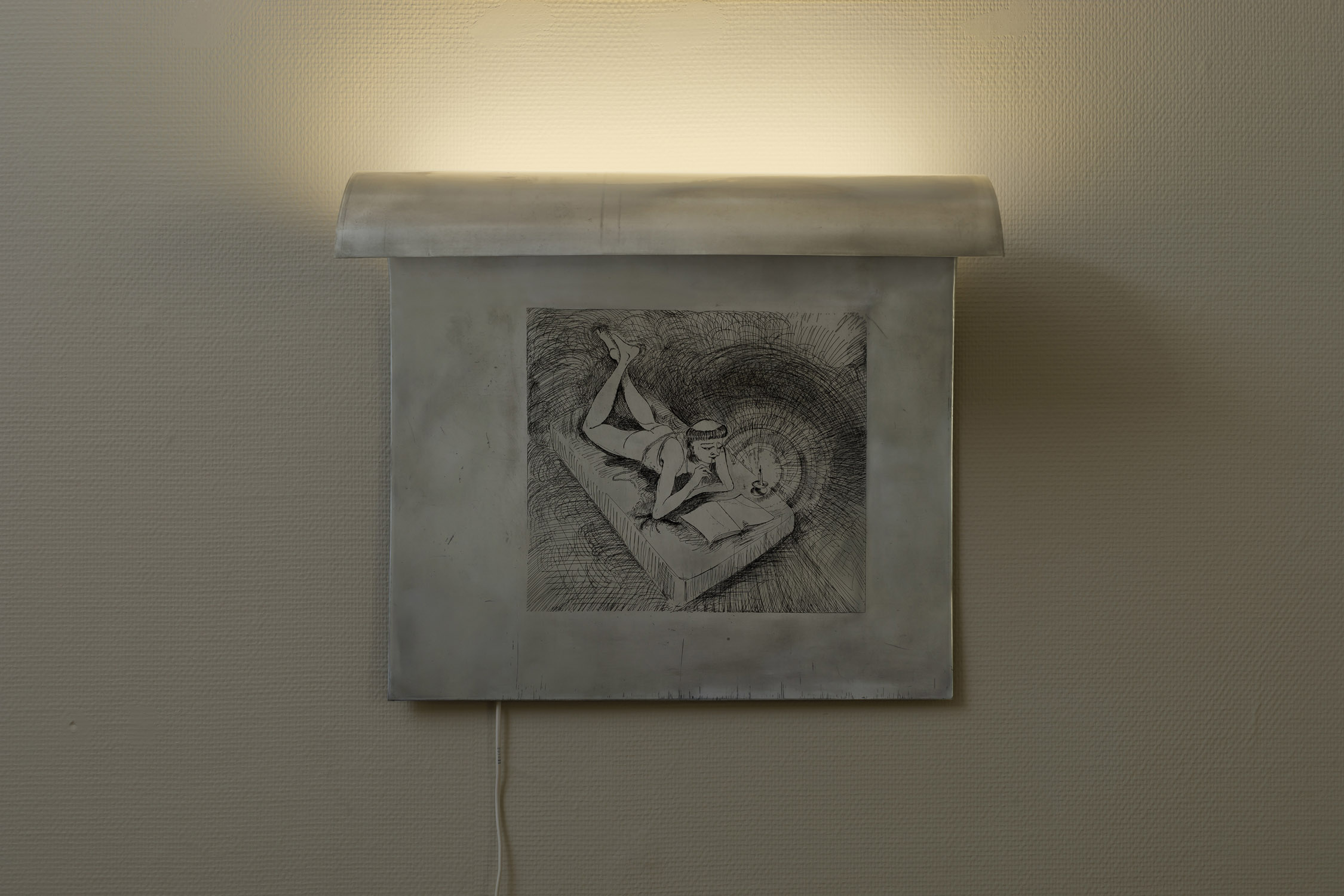

This is because there is an additional caste within Bel Étage, a third; a room dedicated to a single work, itself entitled Bel Étage: a curved etching plate of a young monk, laid out in his monastic cell, journaling by candlelight. Monks have appeared in Carlotta’s work before, as the focus of a body of work depicting medieval monastic copyists and their assumed lurid sensualities. The interest then seemed to be based on a psychedelic dissonance between two contingent types of reproduction: the knowledge that the copyists literally reproduced as a matter of their vocation; and the sexual reproduction that was forbidden to the celibate scribes. The implication being that the precision and concentration necessary to the copyist’s textual reproduction was only possible by the ban on their sexual reproduction. Today, when appreciating the illuminated manuscripts of the middle ages, one can forget that these sublime objects were usually one edition among several. The copyist monks that painstakingly (re)produced these ornate documents by hand had no such intentions of something as obtuse as originality; their purposes were far more practical. There is a similar practicality in Bailly-Borg herself channeling the long forsaken copyist in producing these facsimiles.

What are we to do with the fact that the only works in Bel Étage that do not feature restrained figures are reproductions which are impossible to see without seeing ourselves in their mirrored frames? In 2024, might it not be an apt observation that originality could be conceived of as an absolute restriction imposed on artists? Nonetheless, the interaction between these two classes of work: the originals– the pieces on glass, the paintings that conform to their architectural niches; and the reproductions– simulacra in mirrored frames– is perhaps best understood as analogous to the negotiation between an artist’s response to the restraints of historical derivation, versus the artist’s response to the contemporary constraints of the absolute impossibility of originality. It is from this straight jacket that we see ourselves in Bailly-Borg’s mirrors– imitations, duplicates of ourselves; versions of some long-lost original character-type.

Yet artists, like most humans, are famously adaptable, and this artist has offered us a line of flight from the gauntlet of originality. To borrow again from a medieval lexicon, there is a third estate; a third category; the third caste which is classified only by what it is not. We find this in the architectural bel étage, the floor which is defined by its in-betweenness– existing only through the fact that it is not one of the two lesser floors which bound it from above and below. We find this in Bel Étage where artworks, not unlike ourselves, are restrained between original and copy; constrained by architectures and histories imposed from without. This line of flight figures most directly in Bel Étage: the copyist monk who is not copying– who is (re)producing from no source– but we find this image etched into a printing plate, a component of mechanical reproduction, the material of his obsolescence.

Ryan Cullen, Brussels, September 2024