Artists: Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff

Exhibition title: German Theater 2010-2020

Venue: Fri Art Kunsthalle Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland

Date: September 5 – November 8, 2020

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Fri Art Kunsthalle Fribourg

Note: Exhibition guide is available here

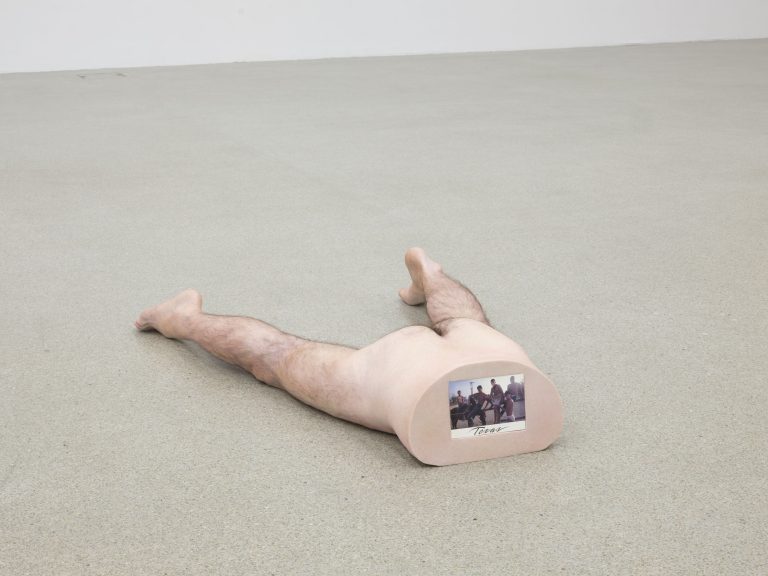

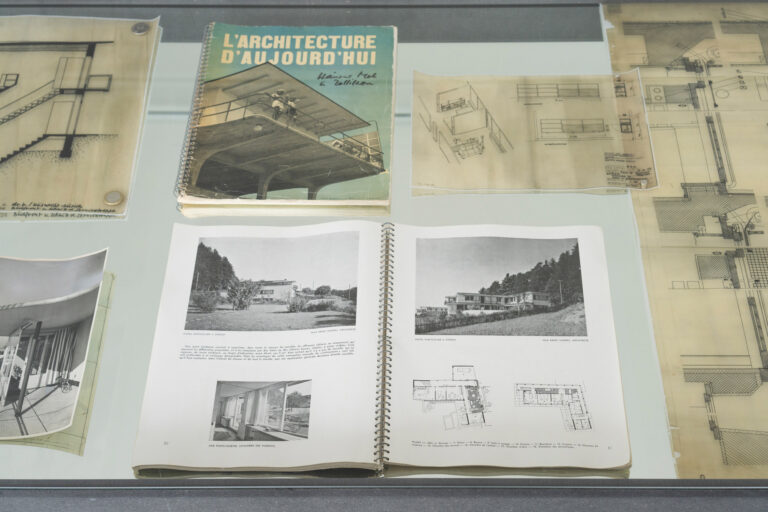

Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff started their collaboration as undergraduate students at The Cooper Union, a small private Lower Manhattan university specializing in engineering, architecture, and fine arts. One of their earliest works in the exhibition, FUKNAB, 2010 (room 6), included a number of choreographed performances that tested, in the campiest fashion, the architectural boundaries of the university’s hugely expensive New Academic Building (i.e. the NAB part of the FUKNAB equation). As a direct result of this urban expansion scheme, along with other poor financial decisions made by the institution’s board, The Cooper Union began to charge admission fees for the first time in its 130 year-old history. The FUKNAB performances involved other students directly impacted by these structural changes, as well as an extended network of friends living in the city. Simultaneously to these scored communal events, Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff began to develop a body of photographic works. The earliest of these pictures in this show (Scheißdreck,2010) was taken after one of their performances at Berlin’s Universität der Künste, which Henkel attended as an exchange student, and which Max Pitegoff crashed, alongside half–a–dozen artists enrolled in various programs of different schools. The photo is of a note written in broken German by Mathieu Malouf, a French–Canadian artist, that asks the Universität der Künste’s janitorial staff to not clean up the mess they had left behind.

These early works carry the seeds of the numerous interfaces the artists would orchestrate throughout the decade in Berlin, where they relocated in 2011. There, the artists would run a string of bars and theaters, where they staged over 40 collaborative theatrical performances. These included plays at New Theater, which they opened in 2013, as well as a number of formal productions in the Grüner Salon of the Volksbühne, the “People’s Theatre”, Berlin’s iconic theatre located on Rosa–Luxemburg–Platz. Their latest project is called TV, a bar that, in its off-hours, functions as a film studio where Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff are currently shooting a sitcom titled Paradise.

Whether a drink, a play, or a sublet, Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff score and choreograph social interactions among artists, teasing the limits of what might define a creative community, however fictional it may be. Their works continuously perform what Benjamin H.D. Buchloh famously called “allegorical procedures” – in that they are infused by, and constantly refer outward to the culture in which they were created. The political framework that conditions the limits of their communal freedom and its eminently fragile autonomy is directly addressed in their plays and performances. Their output aimed at exhibition spaces – which includes most of their photographic work – espouses a viewpoint that is largely peripheral to their community organizing, painting a deadpan picture of the economic scaffolding that sustain such communal exchanges. Following FUKNAB, no direct documentation of their live staged events was made public.

By the turn of the 21st century, Berlin had reinvented itself as an international capital open to a new generation of artists coming from every corner of the world. Yet, in the early 2010s, around the time Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff moved to Berlin, this new metropolis’s laid–back–tech–triumphalism had begun to give way to malaise. Rising rents, the progressive loss of DIY spaces and the growing precarity of their peers, became an integral part of their day–to–day reality. Their work thus yields a wry and bitter–sweet portrait of the German capital in the last decade. Contrarily to the previous generations of self–reflexive artists, the narrative horizon of their work is no longer tied to specific art–historical accounts (i.e. the rise of contemporary art institutions or its markets, the dissolution of the field’s purported autonomy into pop culture at large, or into the immateriality of the Internet, etc.), but immanent to an autopoietic economy of sharing.

Text: Fabrice Stroun and Nicolas Brulhart