Artists: David Douard, Erin Jane Nelson, Flannery Silva, Fran Sharp, Liam Osborne, Maggie Lee, Matt Hinkley, Matthew Linde, Max Brand, Spencer Lai, Trevor Shimizu, Win McCarthy, Zac Segbedzi

Exhibition title: CABIN FEVER CREATURE

Curated by: Centre for Style

Venue: Centre for Style, Melbourne, Australia

Date: October 9, 2015 – January 31, 2016

Photography: images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Centre for Style

A Pompeiian fancy

Michael Spooner

…I was surprised the figures were left barefoot.

Email correspondence, Michael Spooner to Matthew Linde, 1 October 2015

Intro

This text attends to the textures of a life carried across two separate but convergent exhibitions both under the signature ‘Centre for Style’ carried by Matthew Linde’s presence. The first exhibition is a collective work entitled Atrophy Amphitheatre and is an invited inclusion in the Lurid Beauty exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria that examined the influence of Surrealism on Australian art. The second exhibition collects a number of works by local and international artists in the backyard of Matthew Linde’s studio and residence in Fitzroy entitled Cabin Fever Creature.

My intention is not to effect a reconciliation of one exhibition with any other, but to invest in a contingent set of relations. Act 1 positions the shadow of another history that may steward the reader’s advance. Act 2 constructs an archaeology of sorts prompted by, and subsequently applied to, the NGV work. Act 3 is the disclosure by this author of a theatre of mysteries in Fitzroy.

Act 1: Gradiva, be still.

In Lucien Freud’s apartment in Vienna, located above the foot of his analytic couch, is mounted a plaster cast of an ancient Greek fragment depicting a female figure stepping forward, the advancing foot flat and the following foot elevated at the heel. It is suggested that Freud had seen the original fragment in the Museum Chiaramonto during a visit with his brother in 1902 to the Vatican Museum, but it wasn’t until a second sojourn to Rome in 1907 that he went about acquiring the plaster cast described as ‘Gradiva’. His interest in the relief carving was predicated on the 1902 German publication of Wilhelm Jensen’s novel Gradiva, a Pompeiian Fancy; the author prompted by a Munich copy of the Vatican Gradiva. Freud’s interest would be cemented in his 1907 essay Delusion and Dream in Jensen’s Gradiva that addressed phantasms, repression and the mechanisms to uncover them as mirrored in the literary work of Jensen.

Jensen’s novel concerns an archaeologist named Norbert Hanold who falls in love with the ancient relief of Gradiva and thus acquires a plaster copy. He constructs for himself a rich mental picture of her history in the ancient Roman city of Pompeii. This history becomes a delusion, until finally he witnesses her death and possible preservation under ash during the cataclysmic volcanic eruption of Vesuvius. When the haunting image of the young girl from the stone relief appears in the street in front of his house, it leaves him in crisis and he endeavours to travel in mutiny against it, eventually finding himself in the famed site of Pompeii. His delirium continues to place her amongst its ruins when he meets a young woman who appears much like the young woman of his delusions. He proceeds to follow and meet with her a number of times during which she reveals that she speaks German, that her name is Zoe, that she has knowledge of Hanold’s house and that her father is a professor of zoology. With the convergence of this information it dawns on Hanold that the young woman that he has been hallucinating about and now walks in the ruins of Pompeii, is his childhood love Zoe Bertgag, a name that in German also constructs the action of walking. The revelation reconciles her appearance with the image of the Gradiva. They proceed to fall in love and are married.

Freud’s analysis shows how the clinical process is mirrored in Zoe’s actions as she goes about uncovering Harnold’s unconsciously transferred and repressed love for her to the sculpture of Gradiva. Both Freud and Jenson made much of Gradiva’s foot as a consequence, its angle of inclination and its exposure from behind the drapery. In turn much has been written regarding the ideas contained within these commentaries covering everything from feminine transference, heterosexual salvation from homosexual desire and to the unsurprising exposure of European anti-Semitism. And not unexpectedly – given the focus on the unconscious – Gradiva becomes a motif for the Surrealists after the 1930 rupture instigated by Andre Breton. She is first illustrated in the work of Salvador Dali as both muse and erotic provocateur and is named explicitly in the title of Breton’s gallery “Gradiva” in Paris that secured her title prominently with, but above the inscribed names of other surrealist muses; and in the startling painting of her by André Masson that displays her as a fantastical eviscerated heroine.

Act 2: Spitting through dirt and debris

Atrophy Amphitheatre presents a panoramic mise-en-scène along a length of wall broken by a recess and further expressed by a plinth at its base. Across both are arranged items of clothing, recognisable furnishings and associated debris. The initial effect is one of a theatre of rag-pickers. Their toil is collected against a miserable but chocolately backdrop that through its texture does not hide its theatrical efficiency, an effect further emphasised by the deep teal curtains that drop at its edges and frame the material remains of the work. The depth of the plinth is such that it cannot carry all the artefacts and thus corbels and shelves expand the territory of the wall. Further objects such as a flag (Virgina Overell) are hung deus ex machina while the mechanisms for others are exposed, such as an engorged basket strung from a hang-man’s arm (Liam Osbourne). A bed of awakening detritus (Zac Segbedzi) succumbs to the gallery floor.

The spectacle invests in a number of tropes. The most obvious are figures intimated by vacant clothing, the material endowed with their secret daily lives (Blake Barnes). The second is a collection of wrought-iron garden chairs and a table across which two of the vacant but animated spectres conspire. Wire frames at once bed-head and garden edge with naïvely wrought detail confine each of the figures to their place on the wall; one is perceptibly caged, realising bird and conspirator (Natasha Havir Rose Smith); another is held in a corner (Grace Anderson). Smaller artefacts such as a collapsed pair of shoes in red silk (Alison Pyke) and indistinct composites of fabric add to the production of a visible coherence across the wall. The exception is several pieces of debris that present nervously from under one of the shelves (Matt Hinkley), seemingly ready to evade any scrutiny. Rectangular reliefs of brickwork cast in paper and hair (Joshua Petherick) float on the wall surface and divulge the contingency of the vertical plane. With patches of wandering text (Jason Matthew Lee) and a number of en-vogue works on canvas (Josey Kidd-Crowe & Quintessa Matranga), these elements lend the wall some conviction. Nonetheless the impression is one in which the work has been denied a floor.

Thus the wall’s theatricality appears uneasy in the context of the wider gallery show. This understanding is evidenced when the work does momentarily take to the floor, but self-consciously hugs the wall and in the excess of the curtains that falls off the plinth edge, in spite of the carpet that is rolled at the back preventing it from doing the same. This is perhaps less mindful when the curtain rail projects forcefully beyond the edge of the return wall into the space of the gallery and in the strip of pre-install wall left white that bizarrely separates this work from the adjacent work of theatre designers Loudon Sainthill and Hein Heckroth.

The contested terrain between floor and wall, between the experience of one work and that of another – an awareness that things might have spilled out had they been given the opportunity – makes legible the authority of the ‘gallery show’ invitation and importantly discloses the capital that ventures the ‘work (of art, of fashion, of…)’. The hinted genealogy of this collective work alongside the appearance of small ruptures quantifies the aggregation of mummification, museumification and spectacle that emphatically structure the reparation of value.

Nevertheless utmost attention has been paid to the location of each artefact in spite of the difficult pulchritude implied by their material construction. In particular a square of paper tissue rests beneath a floral frog (Kate Meakin), a spiked implement used to secure the stalks of flowers during their arrangement. A single metal rod replaces the stalk, atop which balances a bloom of rolled and knotted fabric given the impression of two phantom limbs. The image is intensely erotic, at once both carefully protected and fearful. In another detail the metal ‘balcony’ that holds the two conversing figures in place (Blake Barnes) is secured over and through the rug that delineates their small theatre. In doing so it exposes an uncertain edict to the matrix of event and artefacts. Protruding from the vertical plane is a metal glove mould that extends towards the end of a straggling wire lasso (Susan Jacobs). It is perhaps a self-conscious inclusion in the context of a show on surrealism in that it recalls the hands of Orpheus that pass through the mercury mirror into the underworld in search of Persephone. Nevertheless I imagine that it gives weight to the greater work as a counter monument – stapled to the wall it attempts and achieves to do nothing – it doesn’t even scratch an itch.

In-spite of the scene that is presented, the material language and nostalgic legibility of items, Atrophy Amphitheatre should not be appreciated as a work of Victorian pathos. Instead, the contrivance realised from the proximity of artefacts, objects and materials is a lithic apparatus. It accomplishes no-less-than the mineralization of all matter that inhabits it. At once shop display, diorama and the half-life of a ruined metropolis, Linde and his contemporaries present the lucid spectacle of an immobilized life, the iconography of bohemian existence regulated and exhausted.

Act 3: The Villa of the Mysteries

The journey from my apartment to Cabin Fever Creatures – a 15 minute walk – and my subsequent enchantment, takes me through the unfolding history of Melbourne, ‘out the back’ along well-worn service lanes and behind edifices of Victorian and Edwardian terraces in various states of gentrification. It is still daylight outside, but a grey pallor casts nothing into relief. Everything could be mistaken for being flat. Earlier in the day I’m informed it is supposed to rain. Now outside, it threatens to.

At the exhibition it is apparent that there is no real discretion in this primitive space of presentation, in the backyard of a terrace house that spills out into a branch of service lane behind and by which I arrived. I invest easily in the marginality of the presentation, framed by the aggregation of half realised architectural forms that drop from the back of the two storey terrace and erode the backyard, but it is quite at loggerheads with the main game seen earlier in the morning at the NGV.

On a shelf in a loosely realized but unfinished cabin lies a crudely drawn plan that establishes the extent and the potential of relations between individual works. Names designate the location and consequently the authors (or owners) of things that hang from the walls and ceiling or shuffle across the floor. From other conversations I quickly establish that there is a diverse geographic difference of production.

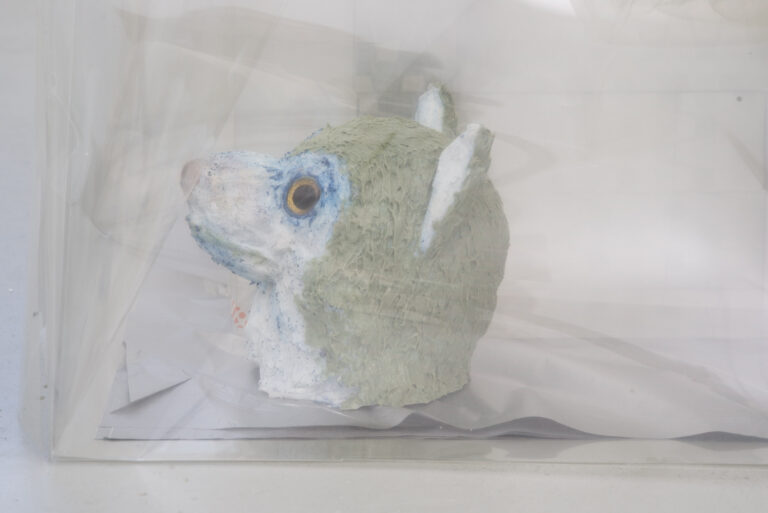

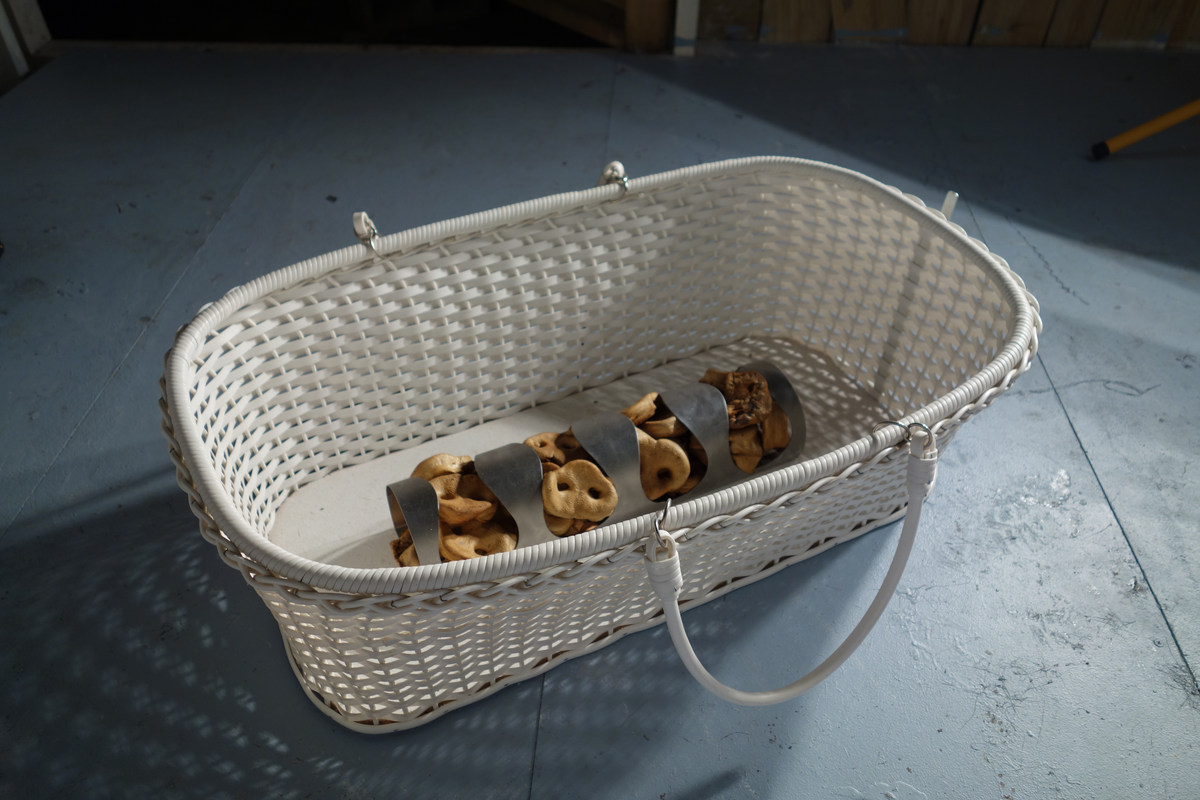

The barely realised floor contains a series of over-sized knuckles conceived by wrought and torn layers of plastic membrane (Max Brand), an abject loaf of pig snouts in a basket (Spencer Lai), and a domesticated totem with uncertain and distressed facial features (Win McCarthy). An almost carnal photograph of a young woman purposely ensnaring herself in a barbed wire fence (Flannery Silva) draws my eye to the corner of the space. From the ceiling hang delicate floating debris, taunting me yet again (Matt Hinkley). These works constitute the foundation for my strongest reactions, particularly the basket and eventually the totem. They move beyond their fabrication, and muffle the typical interrogation of motifs.

Through a small opening into an adjacent space a viscerally wrapped figure straddles a porcelain plinth (Liam Osbourse). A corridor between plot boundary and cabin wall is room enough for a projection of onerous party photographs laced with an exposing flash (Trevor Shimizu). A sketch (Fran Sharp), a mouth cast in the process of swallowing or spitting up (David Douard) and two wall hangings produced independently of each other (Erin Jane Nelson & Zac Segbedzi), bare out some other deferred considerations , but they are held limply in my memory.

The work is dissimilar to each other, more so than the earlier family portrait at the NGV, nevertheless they collectively mobilize some half-reflected persona that does not quite overcome their individual display. It is this utter surprise, and the unnerving sense of these ‘things’, these creatures of bliss and the crepuscular production they slip out from that is so vastly troubling. This haunting cabin and the mysteries contained within remind us of what is hidden, what is overlooked and that can only ever be murmured. What the exhibition suggests is the sudden alchemical transmutation of an inanimate world – particularly at odds with the sedimentation of being at the NGV. Both shows do situate everything we fear to celebrate from the subconscious made up from the very materials that burden our homes, that sit in our backyard, and that clothe our lives hugging the continental edge. But here under a growing darkness the works conceive a communal performance that is genuinely mythic.

With the number of people now increasing in the backyard space there is a vehement sense of territory. The group do not reflect the viewing public as per the NGV show but constitute the spatialization of social relations and epistemological connections that alone can ennoble a fever which these strange things can inhabit. Amongst the bizarre opulence of the backyard and the intimate animism of the most cogent works, any resistance to our individual phantasms withers away.

The frayed edges of this dream pass across the bluestone lanes of Fitzroy. It starts to rain and I take my leave, listening to the soft murmurings of people beyond the walls. Drawn by inclined drains and outlined by half- realised walls my ignoble path back home takes on the apocalyptic calm of a future Pompeii. Against this coincidence of place I am mindful that I walk in the shadow of Gradiva.

Michael Spooner is a lecturer in the Architecture & Urban Design program at RMIT University, Melbourne. His writing, design and teaching projects can be viewed at www.thexhausted.com

David Douard, Sans titre, 2015

David Douard, Sans titre, 2015

Erin Jane Nelson, Experiment on yourself, we’re free’, 2015

Flannery Silva, Roue 67, 2015

Flannery Silva, Roue 67, 2015

Fran Sharp, hot piss, 2015

Liam Osborne, The Outhouse, 2015

Matt Hinkley, 2015

Matt Hinkley, 2015

Max Brand, Untitled, 2015

Max Brand, Untitled, 2015

Max Brand, Untitled, 2015

Spencer Lai, device, 2015

Spencer Lai, device, 2015

Trevor Shimizu, Club, 2002-2012

Trevor Shimizu, Club, 2002-2012

Trevor Shimizu, Club, 2002-2012

Win McCarthy, Untitled, 2015

Win McCarthy, Untitled, 2015

Zac Segbedzi, why wasn’t i told, 2015