Artists: Brandon Ndife & Diane Severin Nguyen

Exhibition title: Minor twin worlds

Venue: Bureau, New York, US

Date: February 22 – March 24, 2019

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Bureau, New York

Bureau is pleased to present Minor twin worlds, a two-person show featuring the photographs of Diane Severin Nguyen and sculptures by Brandon Ndife. The exhibition suggests an adjacent reality, at once speculative and conceivable. The works – though seemingly grounded in familiar, everyday objects and so-called faithful modes of representation – are suffused with a sense of instability and unraveling. Both artists propose systems which are out of balance, where the built human structure is overcome with the non-human. The artists will be exhibiting together for the first time, having recognized a similar set of interests in their work while at Bard College, where they will each complete their MFA this summer. What follows is their dialogue.

DSN: I remember two summers ago when we first came in contact with each other’s practices, there was this immediate recognition of working around the “found object”. What initially felt like an optimistic starting point to bridge our different mediums, the very idea of an “object” began to destabilize over time for both of us, and I can’t decide if our work is coping with the failure of such a category or if it became warped by the specific objects we decided to enter.

BN: What also struck me at first glance was that we were grappling with a journalistic moment in our work. What I mean by that is witnessing and documenting a transition from something recognizable to a strange, fleeting stage of creation, or destruction. We were both interested in the state of “in-between” that can be expressed as physical tensions that we keep coming back to: slow, dripping, dried, frozen, growing, oozing, propagating… Beyond descriptors, these are irresolute states of being which precede much of my sculptural practice.

DSN: Of course, the “journalistic” takes on a really specific meaning within photography; it’s quite inseparable from the violent history of capturing “source material”. The more I accepted my complicity within this lineage, the less an object could just “stand in” (for me or even itself) and be left unscathed. We had to merge; in the way that light fractalized and split our surfaces, burned them, or how the curve of macro glass could exceed the boundaries of our bodies; the optical vocabulary has flesh to it, a concurrent physical aftermath and world-building impetus. My compositional impulse is to make these terms confront one another. For instance, I’m always arranging these evasive wetnesses, which want to speak with the liquid properties of the photographic medium.

BN: Right, in the same way you’re working with your depicted subject but also its inseparability from the medium itself – for me, what contains and houses these destabilized objects is just as important. Everyday things like tables, countertops, cabinets and other basic armatures prop up and become in themselves, the object. A lot of these structures are often built and appropriated from a recently discarded original. Linking or “mapping” opposing sources of material. My days revolve around walking right alongside what I end up including in my sculptures. I find myself snapping mental notes on wayward debris and organic material, oblivious to one another. Perhaps this is what we mean by a journalistic moment?

DSN: Yeah, this traversing of “common” spaces, knowing they can be just as unreliable as they are accessible, in the way an image can shift in social meaning and value depending on who/what is containing it. The mass-produced furniture you employ sculpturally was never built to last but distributed widely nonetheless. The excess of the image, or of a surplus crop does not necessarily feed the bodies or the land that it is excavated from. Though we can’t help but sometimes grieve the loss of an origin point, by re-routing the refuse and tethering the elements to one another, we might propose a new type of life form, one that thrives relationally.

BN: Exactly. The process wedges its way in between this found/made binary we contend with and sort of sets out tendrils, branching out towards other complex possibilities. A hierarchy of what is and maybe what isn’t typified becomes less absolute, less comprehensible when tasked with engineering an environment with no origin – a landscape with unpredictable and indefinite actors and physical boundaries.

DSN: I do like the idea of our practices sharing a certain way of waiting, working from a suspended body of sorts. Not to be mistaken for passivity – waiting can be a hyper-alertness to an environment which is prone to shifts, or even collapse. It’s a precarious position, but one that heightens your attention and pulls you toward overwhelming intimacies. It is unsettling at times, starting out with a material or an object or an idea that is so close to you, and eventually letting go of its given name, which distorts prior access points. It can be hard to tell if this is an act of self-negation or a deeply protective gesture, to reject full comprehension, even to oneself. Of course, it’s almost impossible to empty something of its desire or pain, least of all our own subjectivities.

Uncontrollably so, we are individuals transmitting histories, and there is no linearity to these residues. This haphazard hybridity of the ordinary moment and the potential moment, it can speak to a boundless self, but also a traumatized one.

BN: Right, and this discomfort is where the speculation occurs, the non-place that gets imaged despite looking right at a thing. Complicating our continuity, hybridity has always been more prone to mutation.

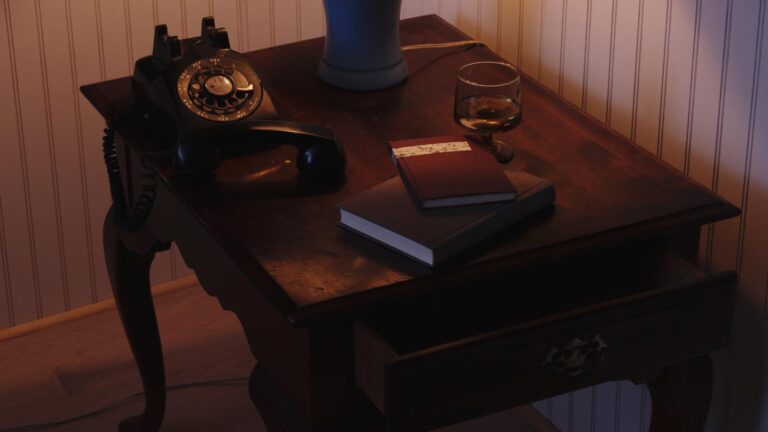

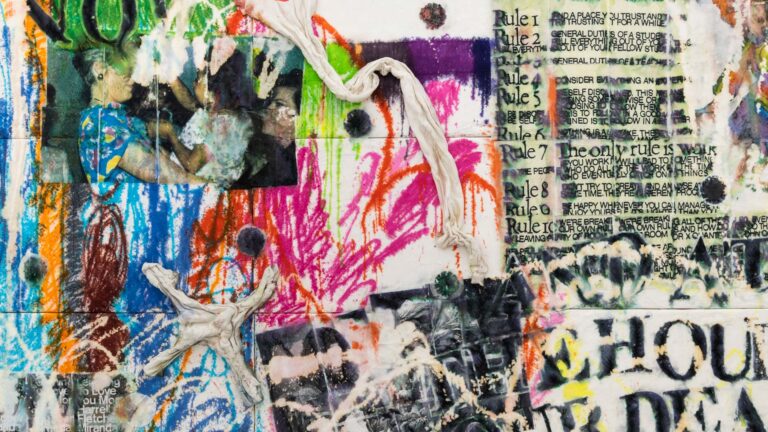

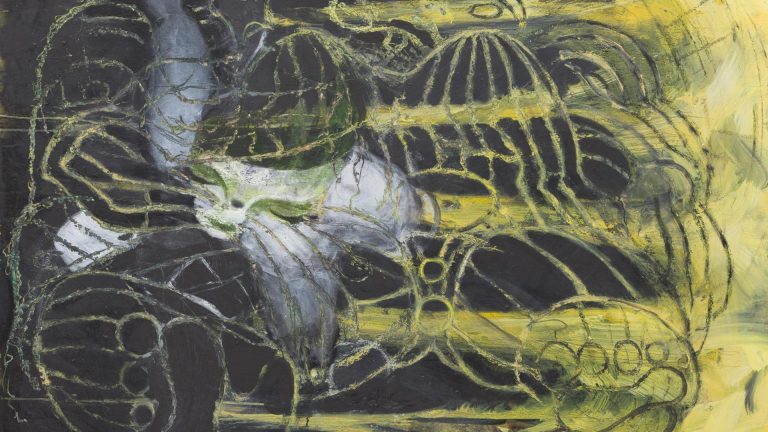

Brandon Ndife & Diane Severin Nguyen, Minor twin worlds, 2019, exhibition view, Bureau, New York

Brandon Ndife & Diane Severin Nguyen, Minor twin worlds, 2019, exhibition view, Bureau, New York

Brandon Ndife & Diane Severin Nguyen, Minor twin worlds, 2019, exhibition view, Bureau, New York

Brandon Ndife & Diane Severin Nguyen, Minor twin worlds, 2019, exhibition view, Bureau, New York

Brandon Ndife, Arid cabinet, 2019, MDF, cast hydrocal, earth pigment, oil paint, hemp, pigmented resin, insulation foam, 29 × 31 ¼ × 24 ½ in.

Brandon Ndife, Organ, 2019, MDF, aluminum sink, PVC tubing, insulation foam, pigmented resin, earth pigment, hemp, 34 ¼ × 28 × 25 ¼ in.

Brandon Ndife, Free or reduced Lunch, 2019, MDF, PVC tubing, insulation foam, pigmented resin, earth pigment, hemp, 40 × 21 ½ × 26 ¼ in.

Brandon Ndife, Nest I, 2019, Fiberglass, aluminum duct, hemp, earth pigment, resin, oil paint, 94 × 14 × 13 in.

Brandon Ndife, Nest II, 2019, Fiberglass, aluminum duct, hemp, earth pigment, resin, oil paint, 91 × 11 × 10 in.

Diane Severin Nguyen, Colonizing Hearts, 2018-2019, LightJet C-print, aluminum frame, 15 × 22 ½ in.

Diane Severin Nguyen, Impulses in-sync, 2018-2019, LightJet C-print, aluminum frame, 15 × 10 in.

Diane Severin Nguyen, Breakthrough Sunrise, 2018-2019, LightJet C-print, aluminum frame, 15 × 10 in.

Diane Severin Nguyen, Swept by the tributary, 2019, LightJet C-print, aluminum frame, 15 × 22 ½ in.

Diane Severin Nguyen, No Feeling Is Final, 2019, LightJet C-print, aluminum frame, 15 × 22 ½ in.

Diane Severin Nguyen, Time-lapse cathedral, 2019, LightJet C-print, aluminum frame, 15 × 10 in.

Diane Severin Nguyen, Shallowed Spectrum, 2019, LightJet C-print, aluminum frame, 15 × 10 in.

Diane Severin Nguyen, Between Two Solitudes, 2019, LightJet C-print, aluminum frame, 15 × 10 in.

Diane Severin Nguyen, Reversible Destiny, 2019, LightJet C-print, aluminum frame, 15 × 10 in.