Artist: Beth Collar

Exhibition title: Bad Zeit

Curated by: Kristina Scepanski

Venue: Westfälischer Kunstverein, Münster, Germany

Date: October 28, 2023 – January 28, 2024

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Westfälischer Kunstverein

Fascinated by mystical and ritual objects, their inherent functions and putative powers, sculptor Beth Collar (b. 1984, Cambridge) is drawn to various forms of religious art. Unlike any other era, the Middle Ages in particular witnessed the use of sculptural representations to communicate, educate, threaten, emotionally affect and chastise. This potential to depict extreme emotional states, to invoke sympathy and empathy, is a key source of inspiration for Beth Collar’s practice as an artist.

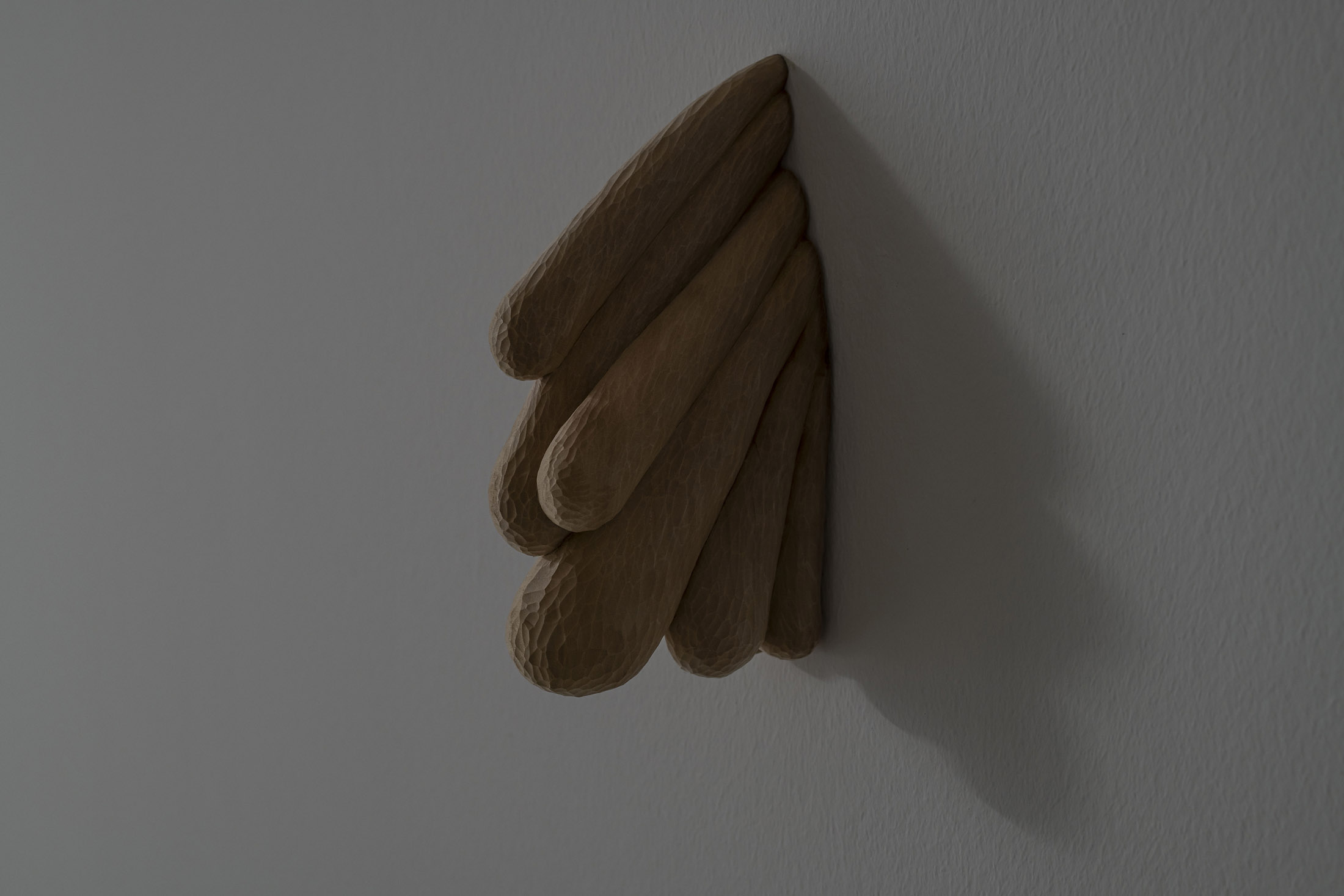

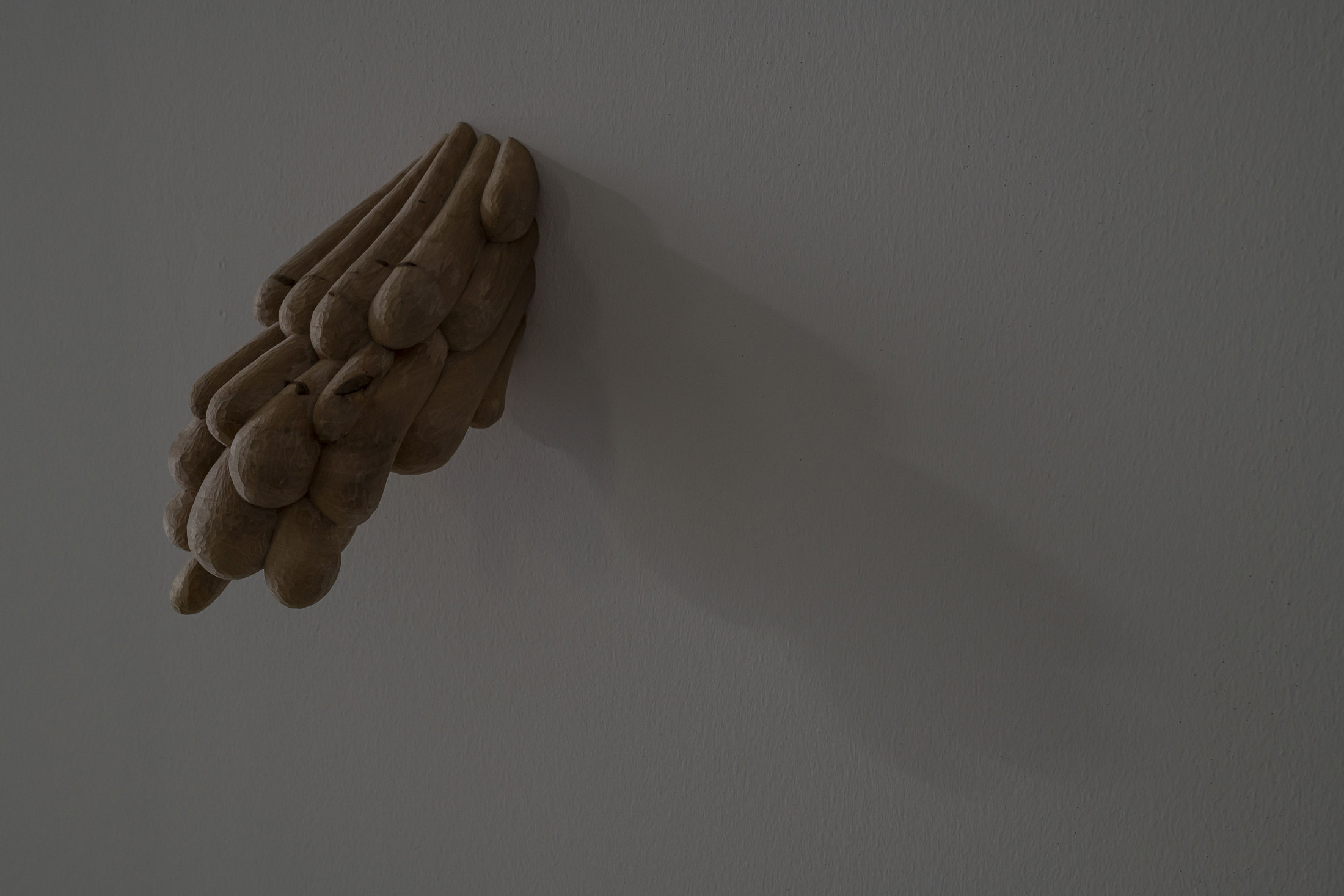

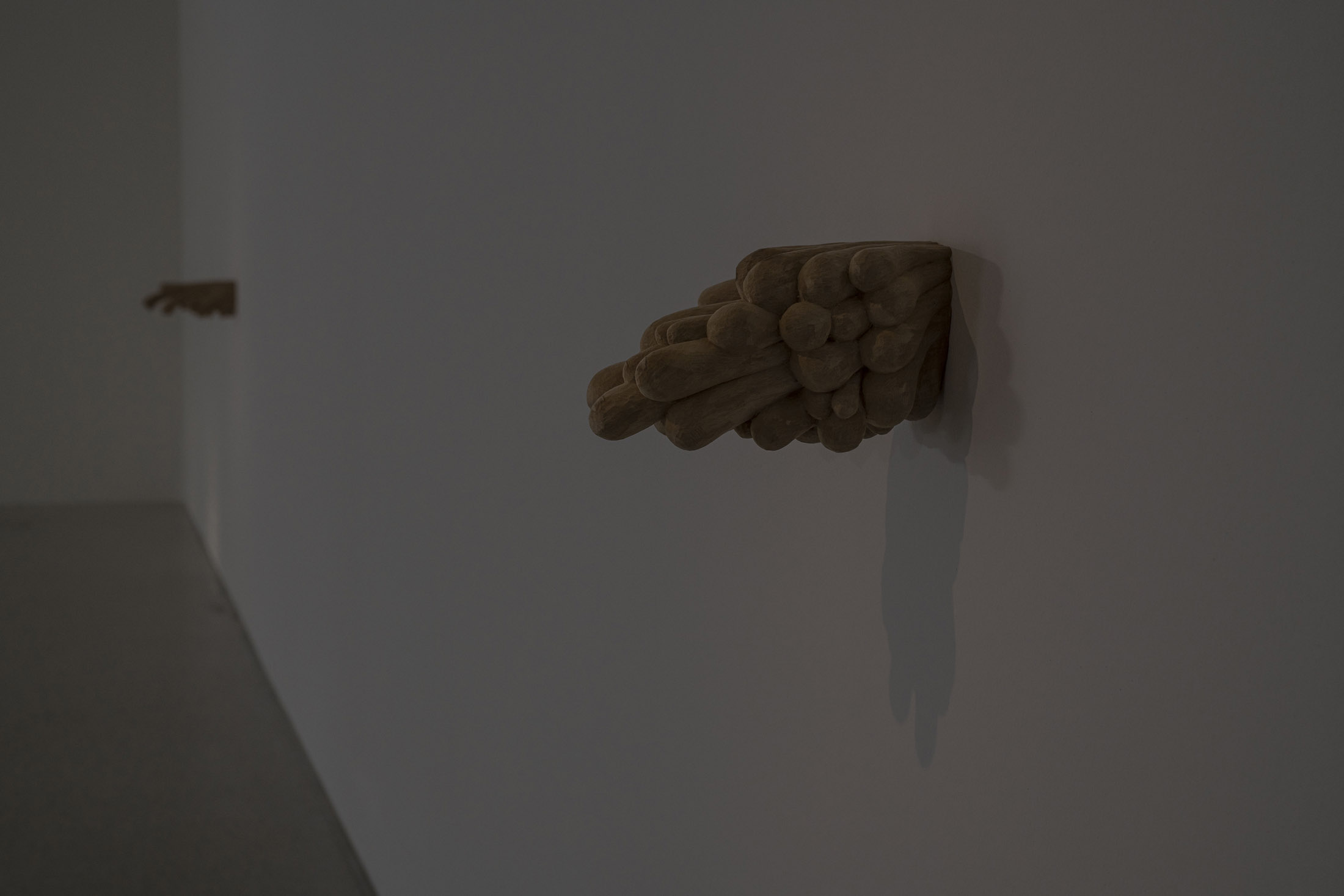

However, alongside the manifestly affective power of objects, the performative moment of their production, the learning and mastering of a (constantly new) craft, the painstaking and time-consuming effort necessary for an object to take shape, are also salient factors here. This is particularly evident in the series titled Spurts that effectively frames the large exhibition space. Since 2021, Collar has been hand-carving these intricate, coagulated, ossified “spurts” out of lime wood, a material that was used – primarily in northern Europe – to make ecclesiastical art objects.

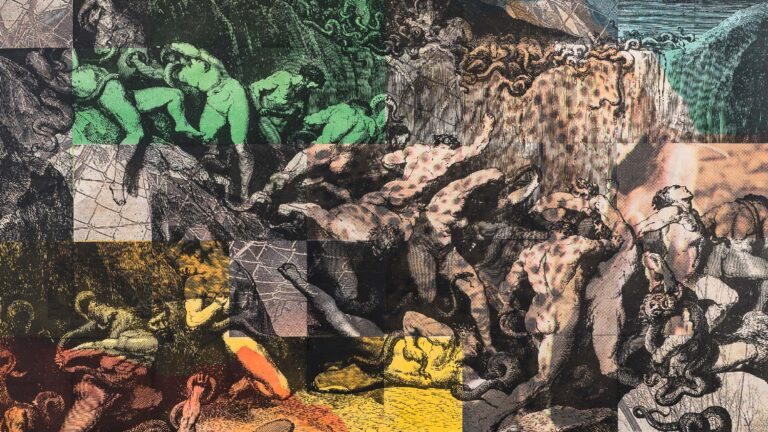

Formally speaking, she references a fourteenth-century Crucifixus dolorosus from Wrocław (Breslau), which can be seen today in the National Museum in Warsaw. This particular type of crucifix, which originated in the Rhineland and spread across Europe during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, is characterised by a Y-shaped cross representing the bifurcation of a tree trunk (aka a ‘tree fork’). The figure of Jesus is also – as the attribute in Latin suggests – racked in pain, presented with manifest wounds and twisted limbs. One element that particularly fascinated Collar about the Wrocław crucifix was the depiction of the blood emerging from the wounds as a thick, viscous coagulation of drops. She identifies the essence of the object’s expression and intention here – a formalisation of horror, violence and suffering, which she revisits in her Spurts series and invests with a wealth of connotations via the mode of the installation. The demands Collar places on sculpture and her desired effect exemplified here recall premodern times and do not necessarily sit with the attention economy of the contemporary art industry. She knows exactly how to analyse which means or forms have been used to trigger emotions in the viewer, especially in sacred and Classical art, breaking them down into their individual constituents and examining how these mechanisms, imbued with current themes, can have an impact in our present-day world.

In her reference to Christian artworks, there is a need for differentiation, especially when trying to understand Collar’s view of Münster. The Gothic forked crucifixes described above, in their explicit formulation and patent emotional intensity, represent the visual language of Catholicism. It was precisely representations of this kind – but also books and paintings – that fell prey to iconoclasm in the wake of the Reformation. Due to the history of the radical Reformation Anabaptists, these developments are part of collective memory, especially in Münster. Beth Collar, who otherwise often compares her hometown Cambridge with Münster, sees this as the most profound difference: she grew up in a wholly reduced iconographic environment shaped by Puritanism, so that for her these crucifixes also emphasise a void – i.e. the suppression of an expressive force – in the cultural history familiar to her.

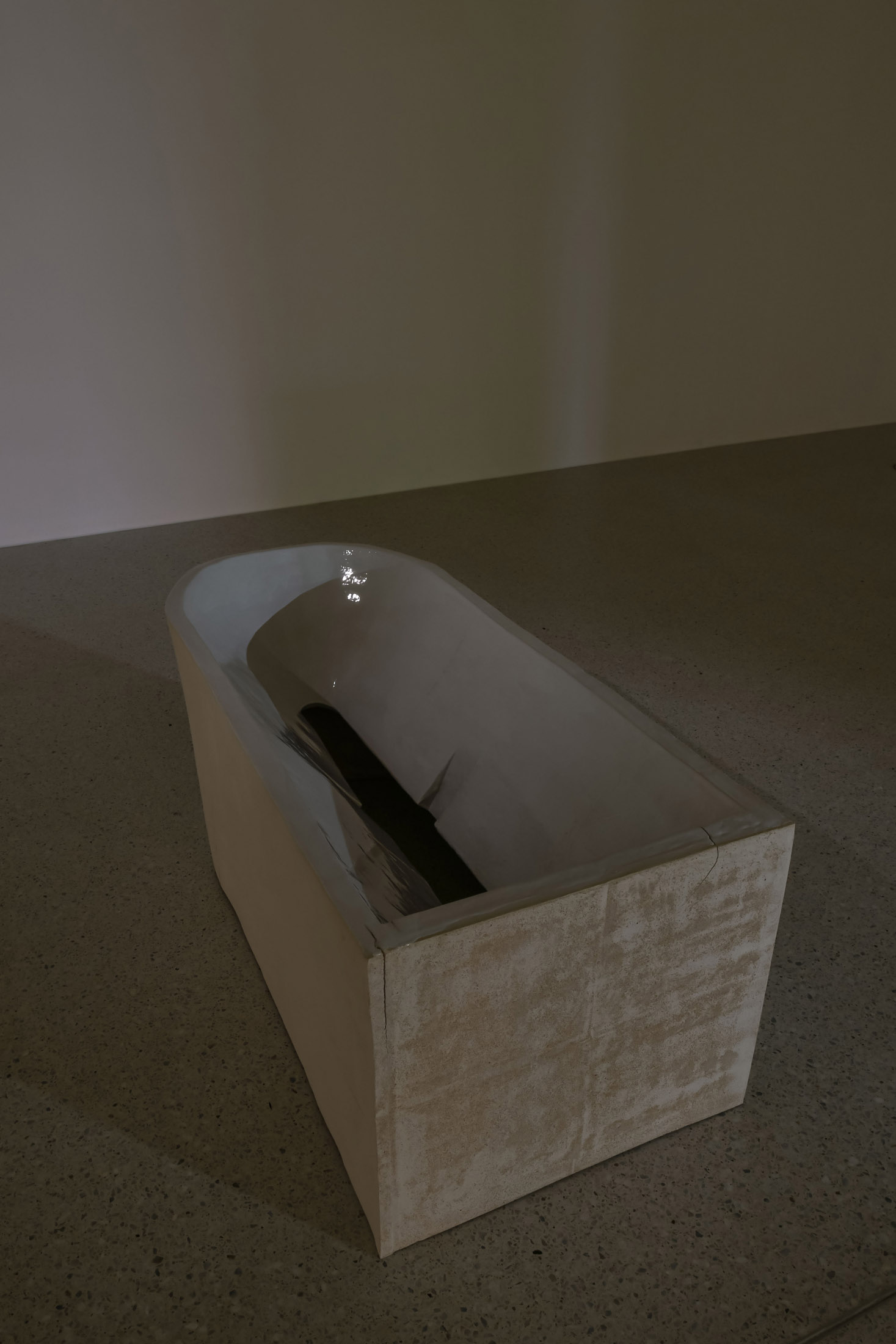

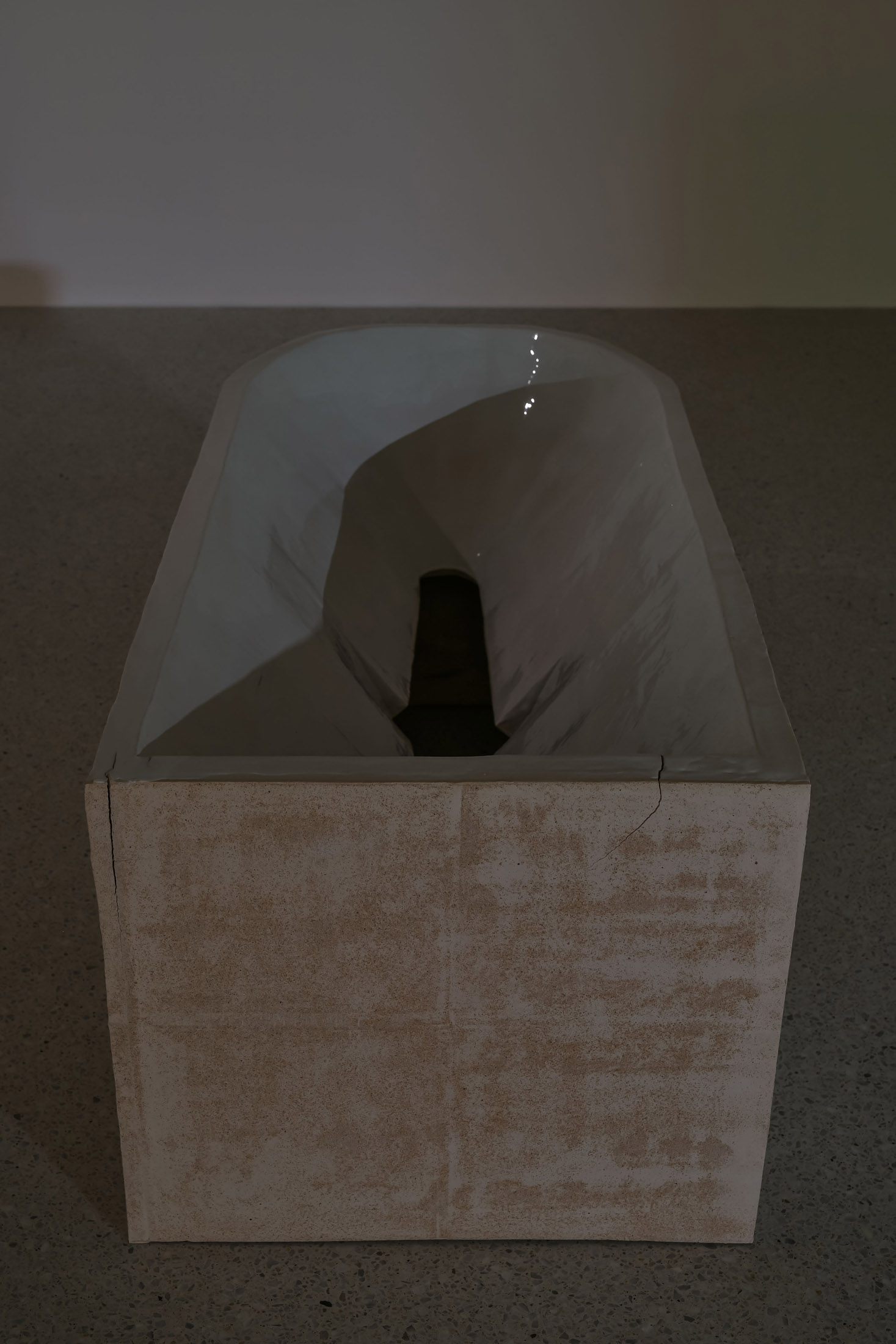

Although Collar usually works in small formats and in relation to the dimensions of the human form, one intention for the exhibition at the Westfälischer Kunstverein was to take the size of the space into account. The centrepiece, then, is a monumental ceramic sculpture, its production representing a remarkable feat of craftsmanship. It is reminiscent of a bathtub, but also recalls a medieval arrowslit. The artist spent several months in Rome, where she studied the traces of Classical Etruscan and Roman civilization and researched the numerous public drinking fountains, the basins of which are often made out of recycled sarcophagi. Occasionally, sculptural elements representing a human body could still be seen in these troughs. A container that served to transport and store a body, and which now is full of water – coffin and bathtub, both adapted to the dimensions of the human body, are not dissimilar in form. The arrowslit, which can be seen when one leans over the object, also encompasses a human body. It conceals him and affords protection so that he can shoot arrows at assailants without sustaining injury. At the same time, however, the position of the person shooting the arrows is highly defensive, since he is in an enclosed and thus otherwise unsafe space: if his place of retreat were to be captured, the supposedly protective space would become a trap. The feeling of safety is exposed as an illusion when one zooms out and looks at the larger context. This core work of the exhibition Bad Zeit reveals one of the associative chains typical of Collar’s practice, which are invariably catalysed and intellectually mobilised by emotions and affects. Even the bath, which encompasses the entire body and connotes immersion, may not always be a blessing, but is interwoven with feelings of vulnerability, complex cultural and religious/historical motifs, such as absolution and baptism.

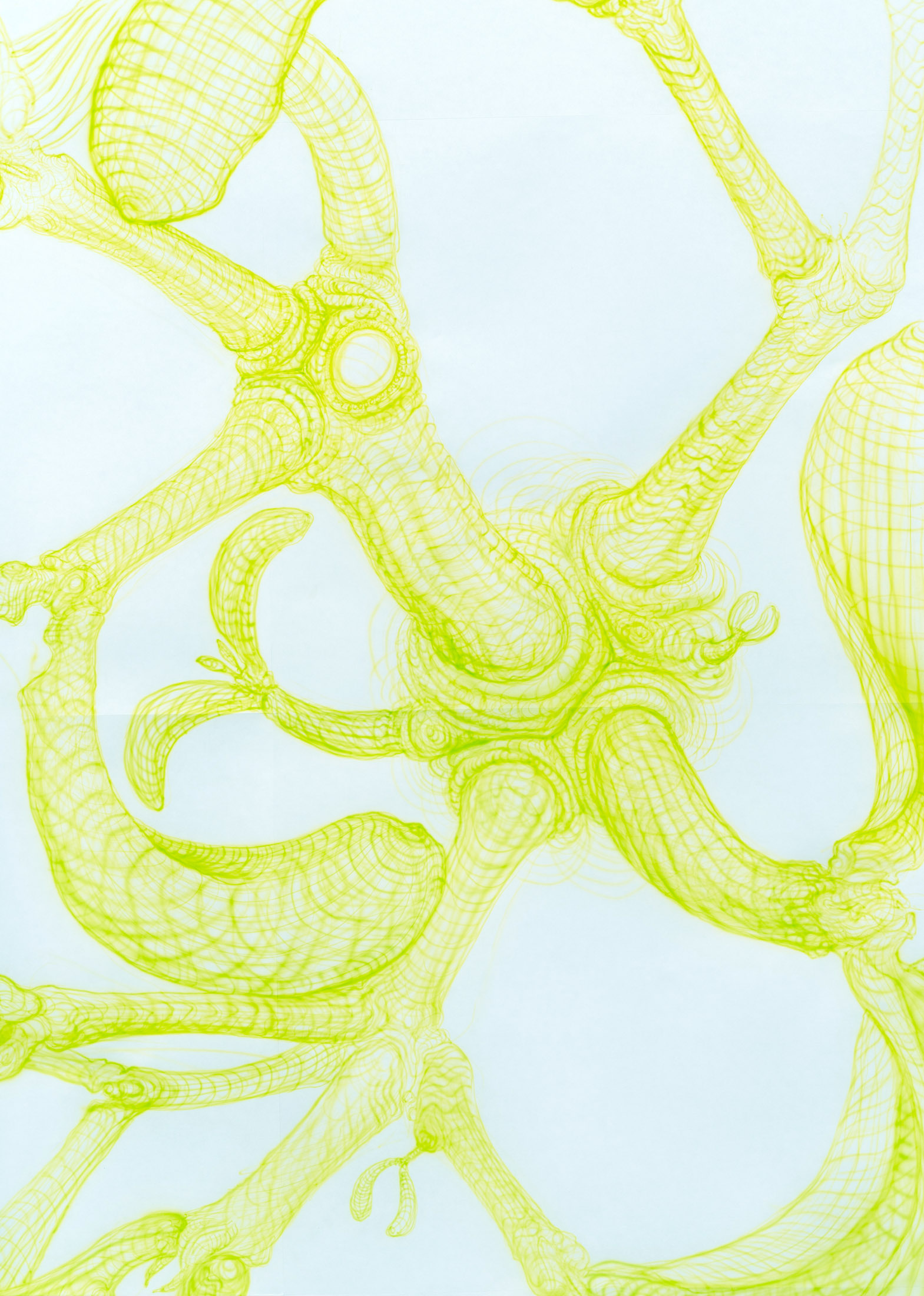

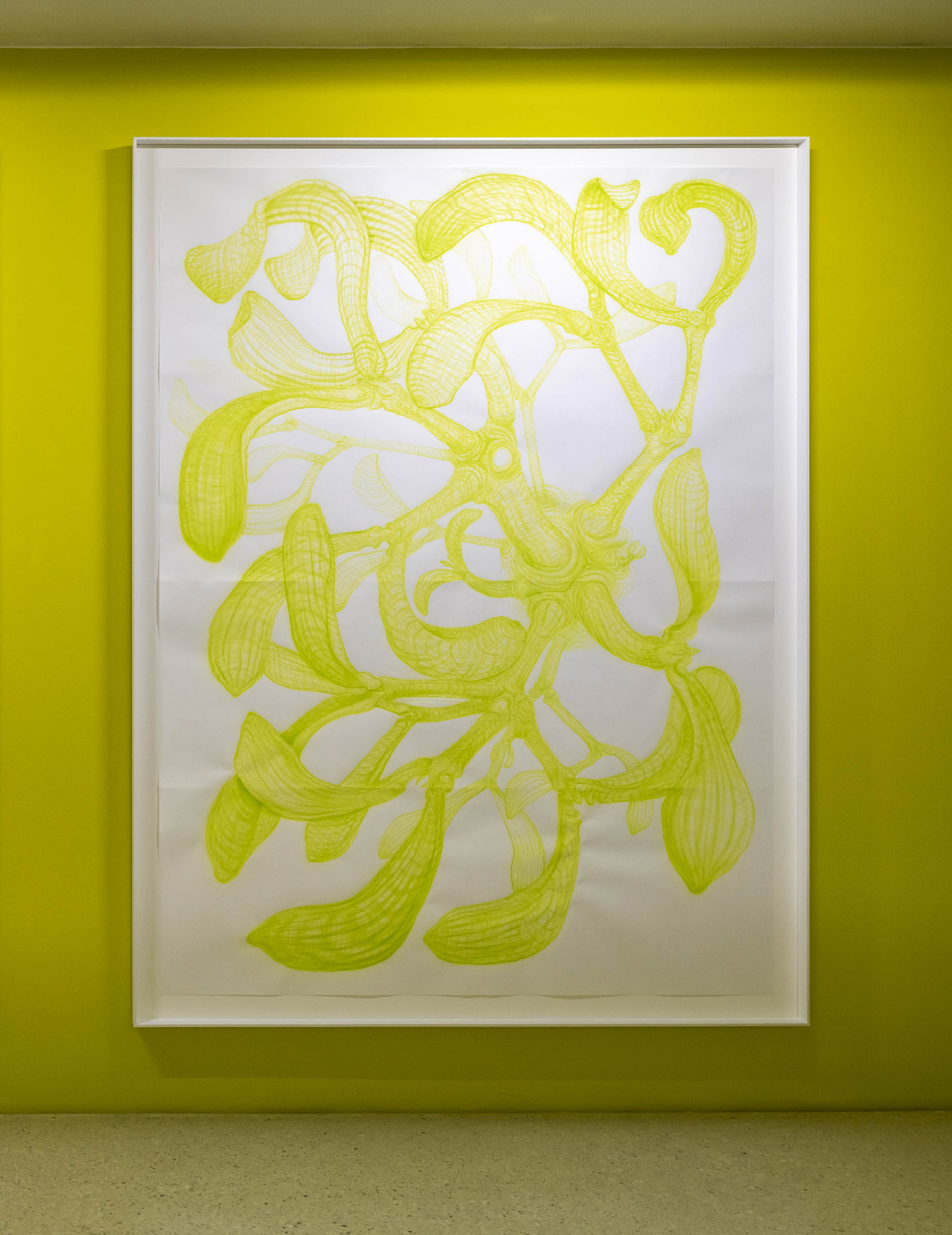

In keeping with these multifaceted references, the large exhibition space is deliberately sparsely lit, thereby further accentuating the aggressive effect of the the glaring light illuminating the adjacent cabinet. The colour of the walls elides here with the tone of the five huge drawings depicting various stages of the mistletoe’s life cycle. Collar uses the monumental size of the drawings, the elision of colour in the room with the drawings and the extreme lighting to create an inhospitable atmosphere: a forensic laboratory, a chapel where false gods are worshipped. Mistletoe, for most of us a harmless, familiar, even benign appurtenance of the contemplative Christmas season, is in fact a parasite that lives on and off other plants, consuming them until they eventually die, which also entails the mistletoe’s own demise: a malevolent economic strategy with an outcome that hasn’t been thought through – for Collar, an image that echoes our modern-day strategies for living, and so the title Primordial Yuppies is commensurate here, too.

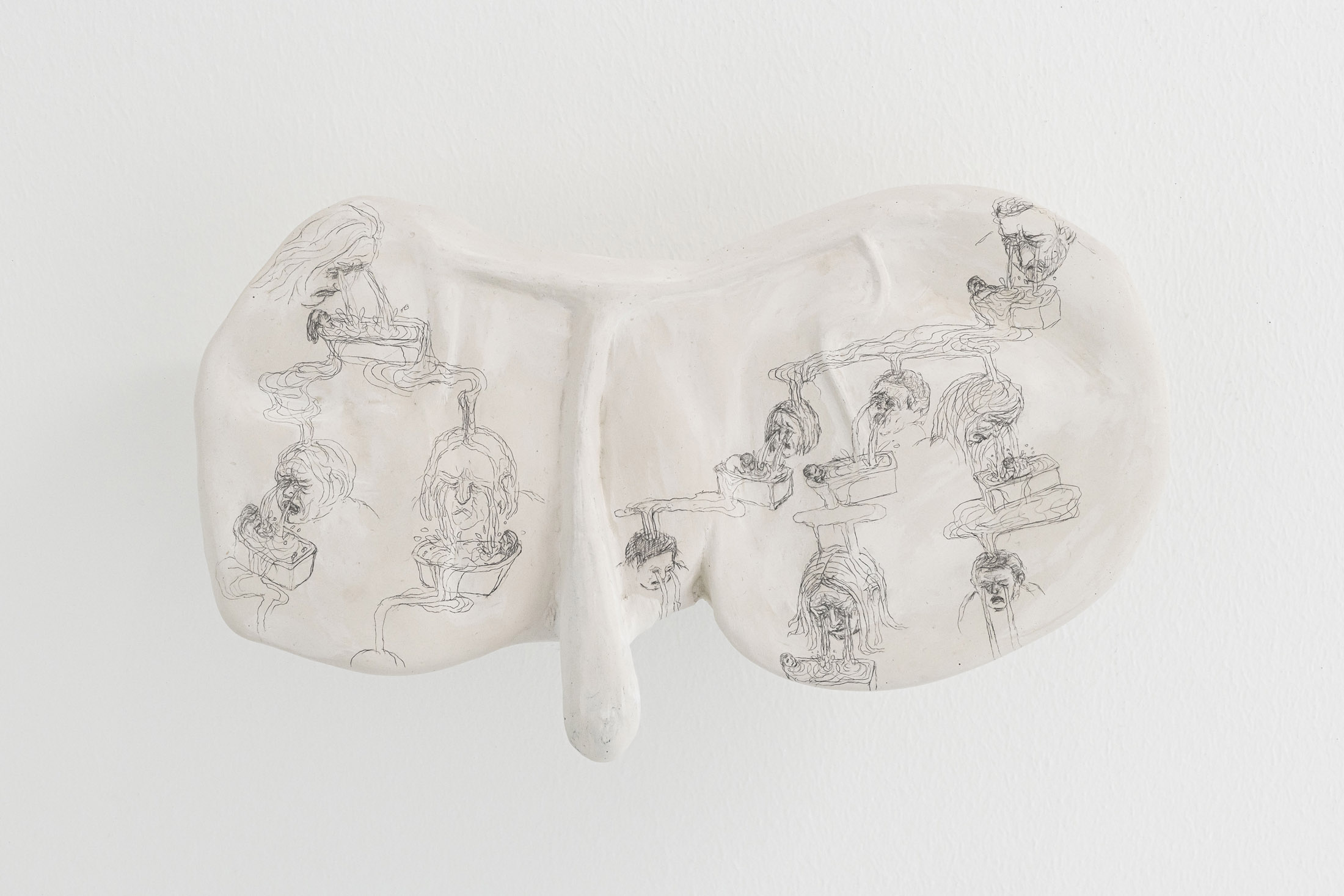

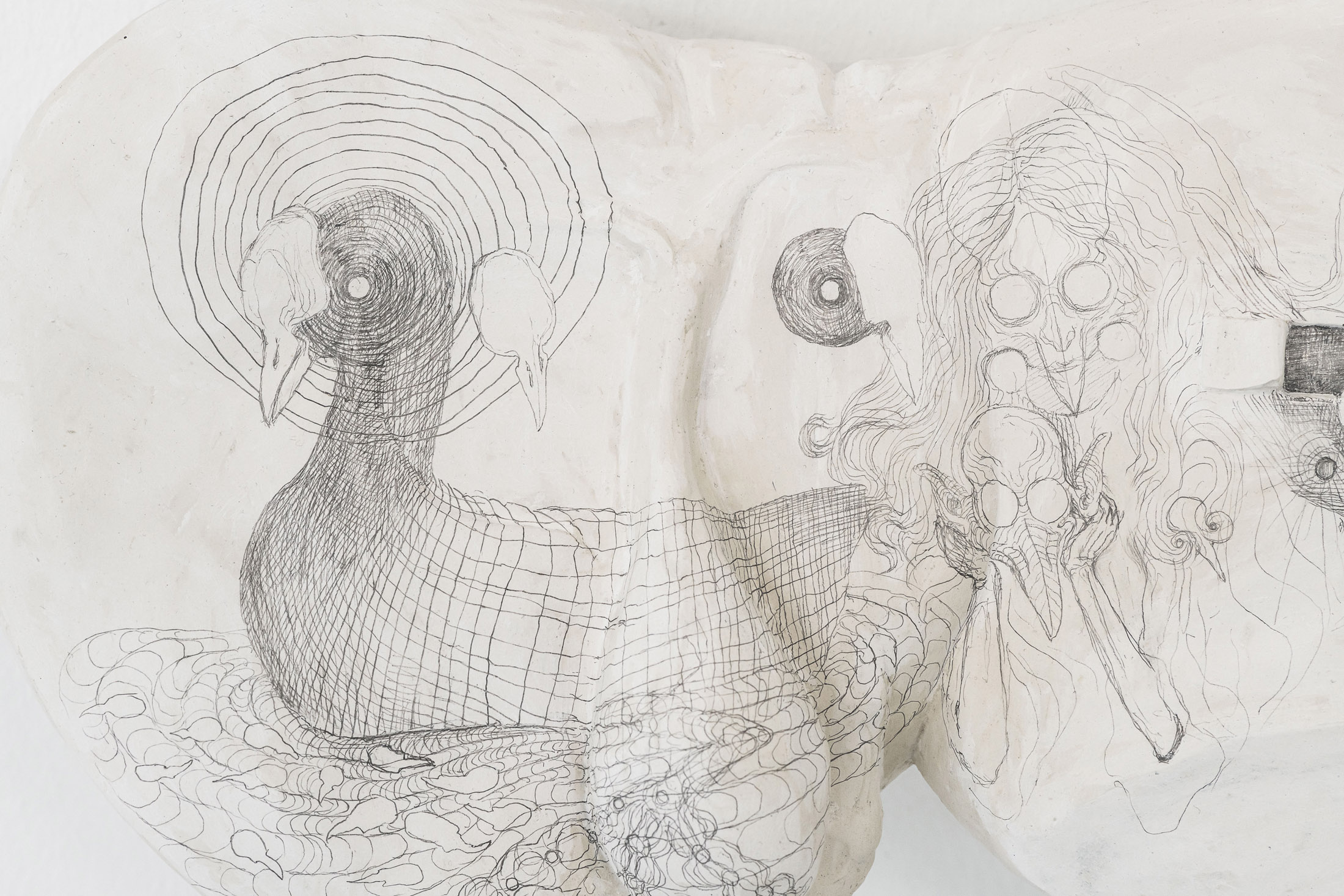

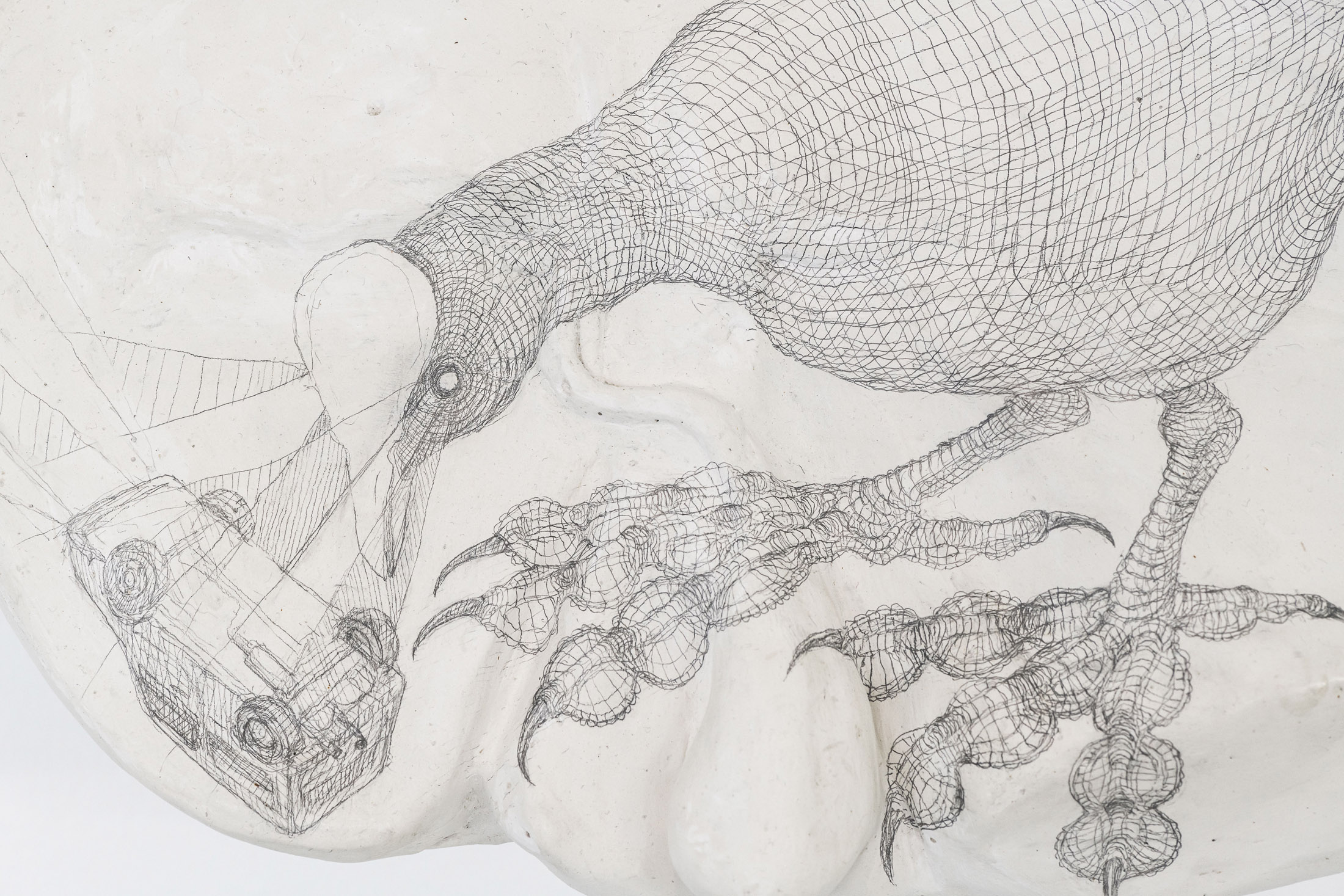

Beth Collar presents another series in the foyer, which is illuminated by natural daylight. There are five ceramic sculptures on view, variations of the same initial form: a liver in rear view with a tear-shaped gall bladder. In Etruscan culture, the spreading of entrails played an important role. Livers of sacrificial animals, such as sheep, from which the haruspex gleaned portents, omens and insights, were used for this purpose. Evidence of this is provided by excavated objects, such as the ‘Liver of Piacenza’ or various votive artefacts depicting body parts. As was customary in Classical times, one can also try to glean meaning in the livers that Collar fashions from these templates. She uses the white ceramic sculptures like the blank pages of a book, transferring drawings from her sketchbooks onto them, thus providing the exhibition with a narrative element that can be read more directly – very much in the spirit of the Haruspex. In addition to the bath and drinking fountains, there are two other groups of motifs: exhausted medieval peasants and a waterfowl. The coot, a common waterfowl with a black body, white markings on the head and red eyes, harbours – in a similar way to mistletoe – a secret behind its harmless appearance. It kills its young according to its assessment of available food. Here, too, a whole web of associations can be spun: the supposedly caring mother bird, with skull-like markings and red eyes, kills her offspring in a water bath. Thus, Bad Zeit (bath time) is most definitely a bad time.

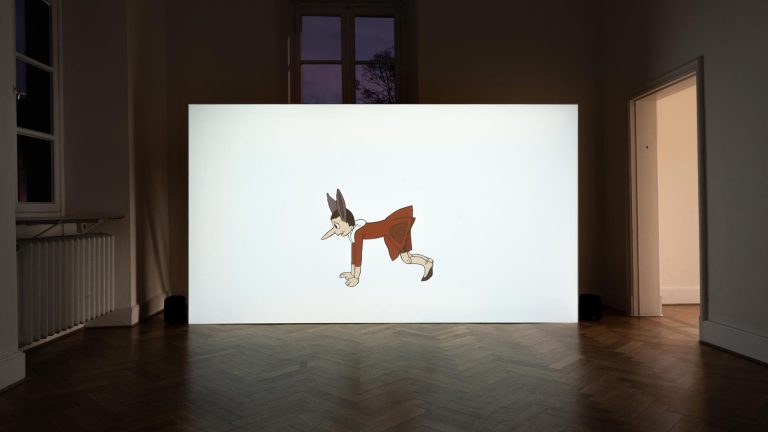

In addition, all of these different objects and series of works are framed by the short video shown in the large exhibition space. Its flickering quality markedly influences the lighting in the space; it refers to the ceramic sculptures in size; its sound accompanies visitors through the exhibition. In the video, Collar assembles visual material she shot in preparation for this exhibition. It is a kind of visual diary, a sketchbook, in which we can identify formal and thematic references that flowed into the making of the exhibited works. However, this is hard work and frustrating, as the images flicker almost uninterruptedly and are accompanied by a scratchy, droning sound. Collar’s phone camera has been faulty for years; its ability to focus, to deliver a stable image is compromised. And thus we become witnesses to pitiful attempts to discern something solid, definitive and resilient among the flickering images. We try to do it ourselves, endeavouring to block out the noise and the background disturbance to discern the one, salient truth, reliable facts and – at best – a modicum of intelligibility. But why should this be easier for us today than it was for the Etruscan Haruspex?