Artist: Bea Schlingelhoff

Exhibition title: PAX

Venue: Kunsthaus Glarus, Glarus, Switzerland

Date: June 30 – November 10, 2019

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Kunsthaus Glarus

Revealing the structures that define our political and social realities is a focus of Bea Schlingelhoff’s (b. 1971, lives and works in Zurich) artistic practice. In so doing, she refers directly to the specific exhibition venues revealing the power relations at work there. For the exhibition in the Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast Bea Schlingelhoff has developed an artistic intervention – PAX – that addresses both the history of the museum as well as specific museum exhibits. Starting point is the «Military and Weapons in Glarus» section of the collection. This collection of military paraphernalia features a plethora of weapons, uniforms, and other objects collected by the Historical Association of the Canton of Glarus and from 1946 until the 1990s by the Museum des Landes Glarus. The collection has been presented in a permanent exhibition for more than twenty years in a separate building – a former carriage house connected to the museum’s inner courtyard. Bea Schlingelhoff is interested in the presence of these objects: what do they tell us and why are they collected? Are they still utilitarian objects or merely decorative exhibits? Why are they aimed directly at the viewer? How old do objects have to be to merit being in a museum? The artist intervenes in the existing presentation by removing all the plexiglas cases that seal off the mostly life-sized vitrines in order to protect the objects and safeguard visitors. As an exhibition amenity, the vitrine is linked to the historical genesis of the museum institution: in churches it once served to enshrine sacral objects, such as relics; later, this functional furnishing established a footing both in the private realm for storing souvenirs and valuable objects as well as in the museum arena, for instance with dioramas representing history and the present. Vitrines isolate, frame, protect, sublimate, and domesticate. They create presence; aspects of political or social realities are legitimized and conveyed. The vitrine is both a predecessor of and a metaphor for the museum – a miniature model of the museum per se. In the collection of military paraphernalia, it also creates a separation barrier between the visitors and the potentially dangerous exhibits. It creates a distance, a framework, and neutralizes the violent and power-wielding objects.

Now the weapons are surrendered to the visitors and beg to be touched. The potential proximity to the military paraphernalia here makes their fetish character immediate and obvious. The objects exude a presence but are still taken out of service. But the museum disarmament is deceptive: new safeguards again make the exhibits – most are from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries but some of the most recent additions are contemporary – untouchable objects and deny them their original use. Legal provisions must be abided by when storing and presenting them, even when these visible security procedures render them now completely useless. Intervening with the existing exhibition Bea Schlingelhoffs exhibition poses questions concerning political and historiographical representation: Which objects do the museums fetishize? Which histories and stories are told? How does a weapons collection differ from a collection of paintings? Is the decommissioning of these original utilitarian objects in museum vitrines and on walls a symbolic upgrading or a disarmament? The exhibition does not provide clear answers, but functions by juxtaposing certain aspects. The PAX poster quotes the Berlin Apell, an East German peace manifesto from 1982. At the European epicenter of the Cold War, this call for disarmament demanded a lasting peace in response to the shifting phases of war and peace that shaped twentieth-century Europe. The end of the Cold War sapped the urgency of the peace movement at the time. It appears almost frighteningly historical even when armed conflicts have simply moved to other regions of the world. When peace movements are reignited in response to such confrontations – for instance during the invasion of Iraq in the 2000s – they sometimes convey the impression of being trapped in a pop-cultural gesture. Not only the framing of the rainbow banner evokes this – like the PEACE or PACE flags of the 2000s that adorned souvenir shops, flag shops, fashion shows, and urban balconies – but the invitation card citing the cover of Blondie’s album Heart of Glass could also be read as a reference to this connection. Homage is also paid to the seductive aesthetics and the literary language of anti-war poems which are available for reading on the Kunsthaus Glarus website as an extended part of the exhibition.

The other component of Piece of Glass takes place in the temporary exhibition spaces. The plexiglas cases from the vitrines are positioned together in the center of each room under the existing, ceiling-mounted lighting systems. At first glance, we seem to find ourselves in the back rooms of the opulent museum building where the display cases have been placed for storage. Are they ready to be installed or are they no longer in use? Arranged in illuminated «arenas», the plexiglas cases are almost transformed into minimalist sculptures. The patina of usage – dust and scratches, traces of dirt, and the inscriptions – matches the idea of an artwork made out of industrial materials supposedly deprived of all forms of individual or artisanal artistic authorship. But here it is only a casual quote of such an – often too serious – aesthetic. The inscriptions on the cases still tell a fragmentary story. At the same time, they almost become opaque objects that reflect back the viewer’s image in reverse. The once private rooms are left in their original state. Only the warm, domestic lighting has been replaced by the artificial lights of the museum: bright daylight LED tubes and spots.

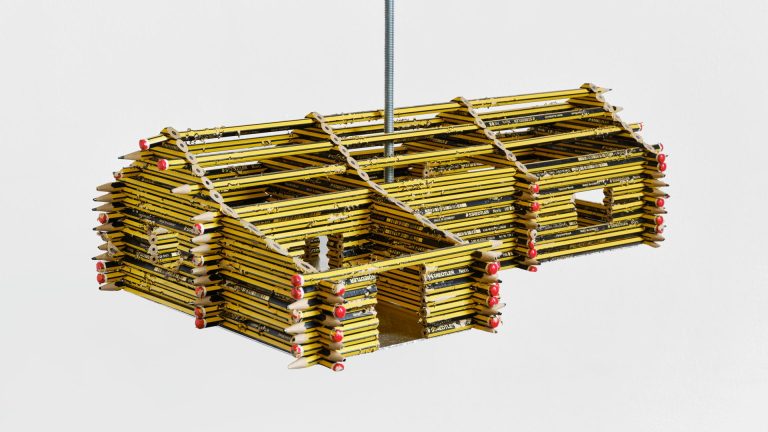

The Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast not only houses the historic collections of the canton, the protected landmark and opulent building – built between 1642 and 1648 – is itself already museal. The building once served as the private residence of the Glarus guards officer Kaspar Freuler (1595-1651) and was built with funds he could amass from his European wartime dealings. For several centuries, Freuler Palace was owned by the family of the descendants of Kaspar Freuler. In 1946, the museum of the canton opened in the former residence building, thus providing a permanent venue for the collection of the historical society. A halberd was the first object in the museum’s inventory. It is not a coincidence that such an exhibit marks beginning of the history of the collection given the emphasis on historical collections at that time: weapons formed the centerpiece of many historical collections. But the link between collection activities and weaponry is also the central focus in an indirect way: art collections often originated with means acquired militarily. A link between these two economies – art and warfare – with their own sets of rules and conditions of production can be traced to the present day. In addition, both art and warfare are understood as crafts whose function, under various auspices depending on their historical conditions, stand back behind aesthetics or form. In the collection of military paraphernalia, for example, halberds, whose sole function is as representative jewelry, represent wealth and power akin to paintings and portraits. The catalog of the military history collection describes the mercenary system as a craft. Just as precise in both craftmanship and history is the detailed relief of the Battle of Berezina, which took the creators of the exhibition a long time to produce.

Divided into two parts, the exhibition features two titles: PAX and Piece of Glass not only refer to the exhibition’s formal structure, but also suggest two possible readings. On the one hand, PAX asks, for instance, what role such a collection plays in the context of the peace movements of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Can a “disarmament” of the military paraphernalia collection help to facilitate a different narration of these objects? On the other hand, Piece of Glass is not least about questions of artistic production and authorship. Which structural and economic conditions of the institutions become part of the artistic production process? What role can the artist take today in relation to social and political issues? The merging of local and historical contexts with contemporary art is always tied to temptations and burdens alike. The hope that art will be able to provide a new perspective on what is already known precludes the opportunity to assimilate a historical context or contribute to appealing gaps in historiography. These two, at-times-conflicting perspectives and interests do not always intersect. This working relationship – between commissioned work and carte blanche – brings ambivalences along with it: art becomes decoration or, in turn, the context is used for other purposes and “performed.” This exhibition was created neither in the artist’s studio as a commission nor on the basis of thematic guidelines, but is instead the result of a complex negotiation process. Accordingly, the work is produced not only by the artist, the exhibition is the result of numerous participants: on the one hand of (artistic) wage labor and the conceptual contributions of all those involved including the two curators of the institutions, the collection manager, but on the other hand of the Glarus cantonal police. Almost the entire production budget for this exhibition goes to covering this involvement. Also part of the exhibition – on view in the special exhibition spaces – is the artist-authored Wimminfesto, which advocates for gender equality in art institutions. Bea Schlingelhoff has used this text in all of her exhibitions since 2017, which is not least also an exploration of the possibilities of political languages, whereby the contracting parties are free to sign it or propose amendments. The font designed by the artist from Anne-Marie Piguet is used for the layout. The also tongue-in-cheek intervention in the existing collection, which as a gesture may provoke and annoy or gratify at first glance, not only opens up various possible narratives about war and peace, but also shows what the collected object can be beyond its static persistence.

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, detail; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, detail; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, detail; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, detail; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, detail; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, detail; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, detail; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, installation view; photo: Gunnar Meier

Bea Schlingelhoff, Museum des Landes Glarus Freulerpalast: Bea Schlingelhoff – Piece of Glass, 2019, detail; photo: Gunnar Meier