Artist: Augustas Serapinas

Exhibition title: February 13th

Venue: Emalin, London, UK

Date: April 5 – May 18, 2019

Photography: Plastiques / all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Emalin

Emalin is pleased to present February 13th, Augustas Serapinas‘ second exhibition at the gallery.

Augustas Serapinas (b. 1990 in Vilnius, Lithuania) lives and works in Vilnius. He completed his BFA at the Vilnius Academy of Arts. Upcoming exhibitions include May You Live In Interesting Times, 58th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia (Venice, IT. 2019). Exhibitions include Waiting For Another Time, Apalazzo Gallery (Brescia, IT. 2018); Where is Luna?, CURA Basement (Roma, IT. 2018); Blue Pen, David Dale Gallery (Glasgow, UK. 2018); Give Up The Ghost, curated by Vincent Honoré, Baltic Triennial 13 (Vilnius, LT. 2018); Everything Was Forever, Until it Was No More, RIBOCA1 Riga Biennial of Contemporary Art (Riga, LV. 2018); How To Live Together, Kunsthalle Wien (Vienna, AU. 2017); Four Sheds, Fogo Island Arts (New-foundland, CA. 2016); Housewarming, Emalin (London, UK. 2016); Phillip, Lukas & Isidora, SALTS (Basel, CH. 2015).

February 13th

Caroline Elbaor

With “February 13th,” the second exhibition by Lithuani-an-born-and-based Augustas Serapinas at Emalin in London, the artist brings -―quite literally―- a group of snowmen whose journeys eponymously began on the date of the exhibition’s title. The snowy statues were built by anonymous children in Vilnius, after which they were plucked from playgrounds, loaded in a van and driven to the United Kingdom, where they now rest comfortably in a freezer at the gallery.

Any romantic will fall prey to anthropomorphising the-se figures; it doesn’t help that when discussing the project with Serapinas, he is quick to mention that February 13th is also the snowmen’s “birthday.” Yet, upon further analysis, perhaps a sen-timental reaction is indeed the artist’s original intent: by drawing upon relatable childhood motifs, Serapinas has once again infused the physical installation with deeply human histories, thus creating a work that positions the personal as an object of art in itself.

In her 1993 text, La révolte intime, Julia Kristeva defined the medium of installation, claiming that “in the place of an ‘ob-ject,’ [installation] sought to place us in a space at the limits of the sacred, and asked us not to contemplate images but to com-municate with beings.” Kristeva’s interpretation of the artform was near-prophetic when considering it in relation to Serapinas’ career thus far; his investigation of both physical and metaphorical spaces for communication elevates human connection to a hallowed status, lending itself to the air of vulnerability inherent in all of his works.

This sense of the vulnerable is particularly poignant in the case of “February 13th”―a project which is, at its core, about childhood, addressed by way of the youths that created the snow figures, or as Serapinas phrases it, the snowmen’s “origin of kids.” Admittedly, the concept of displaced Lithuanian snowmen and snowballs situated in a London gallery may first conjure associ-ations with spectacle or the absurd. The element of silliness, ho-wever, is self-aware; like a mischievous youth himself, Serapinas furtively snatched the snowmen from their playground posts during the school day, presumably later leaving their makers bewildered as to where their handiwork could have gone while they were in class.

During our conversations, we were often distracted by the impulse to dream up imaginary situations surrounding the snow-men’s absence. Because Serapinas remains hesitant to ascribe spe-cific narratives within his work, I mistook these talks for shared daydreaming, only realising later that his suggestion that the snow-men had actually been “saved” was a weighty statement disguised behind a playful veneer. The logic for this scenario was centred around the statues’ characteristic ephemerality, and argued that supplanting the dangerous outdoors for the safety of a cooling unit eliminated threats posed not only by natural forces, but also by the hands of the youths themselves, who often (somewhat inexplicably) demolish their own creations, or those belonging to schoolyard rivals. (It is important to note that one of the snowmen in the exhibition is, in fact, ‘destroyed;’ of equal relevance is that this presentation is true to the fashion in which Serapinas first found it.)

At its simplest, the “rescued snowmen” argument ultima-tely boils down to the idea of preserving by removing. It is true that the snowmen were spared a fate in which they would have melted (or otherwise) soon after their February 13th birth date. As a result, the snowmen that were transported from Lithuania to the United Kingdom do not serve as a final product in themselves; rather, they take on a near-symbolic status. Like a souvenir, they are the representations of human experience and interaction, th-rough which the tangible objects we see are a result―a memento, or a scar.

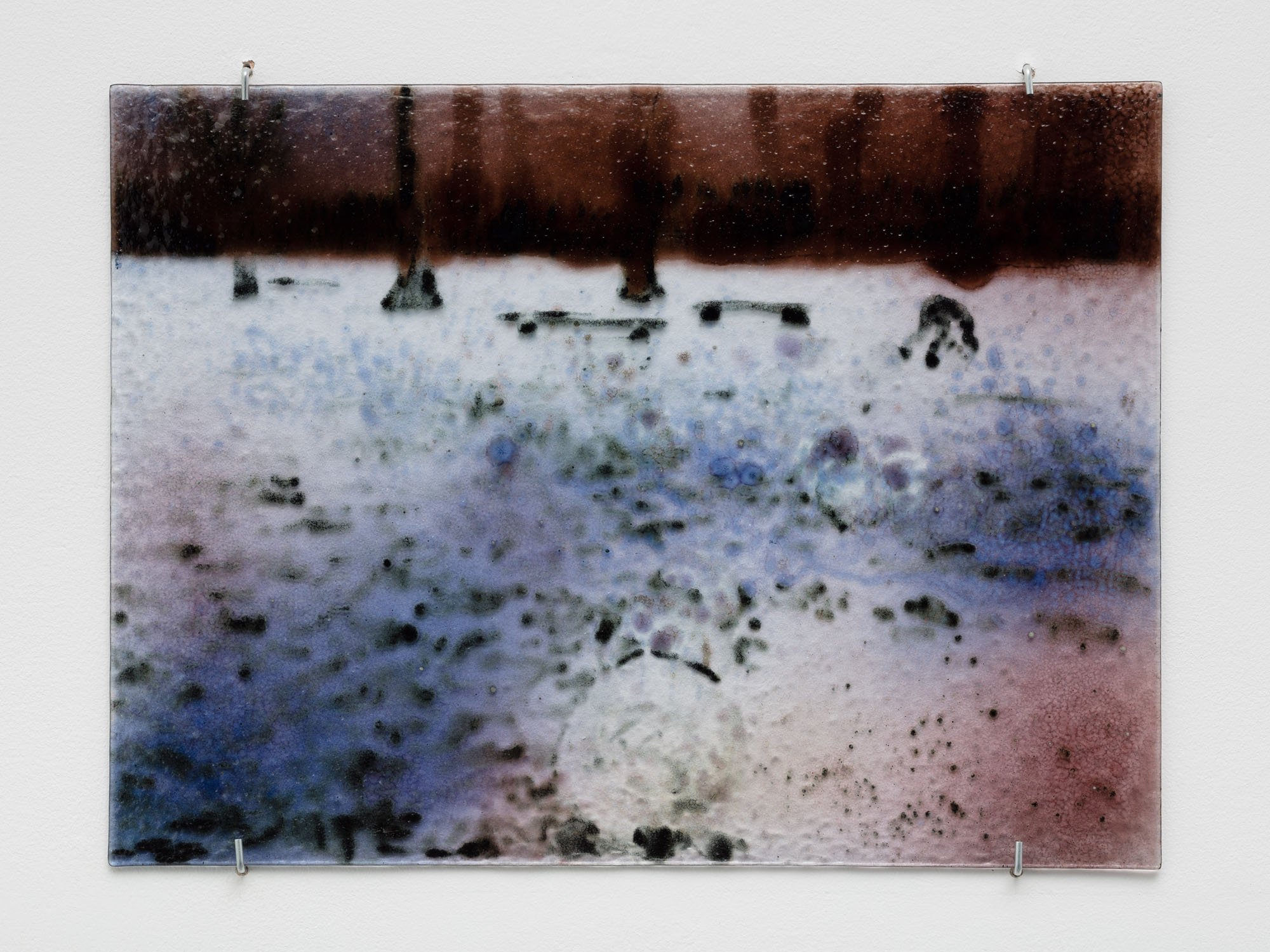

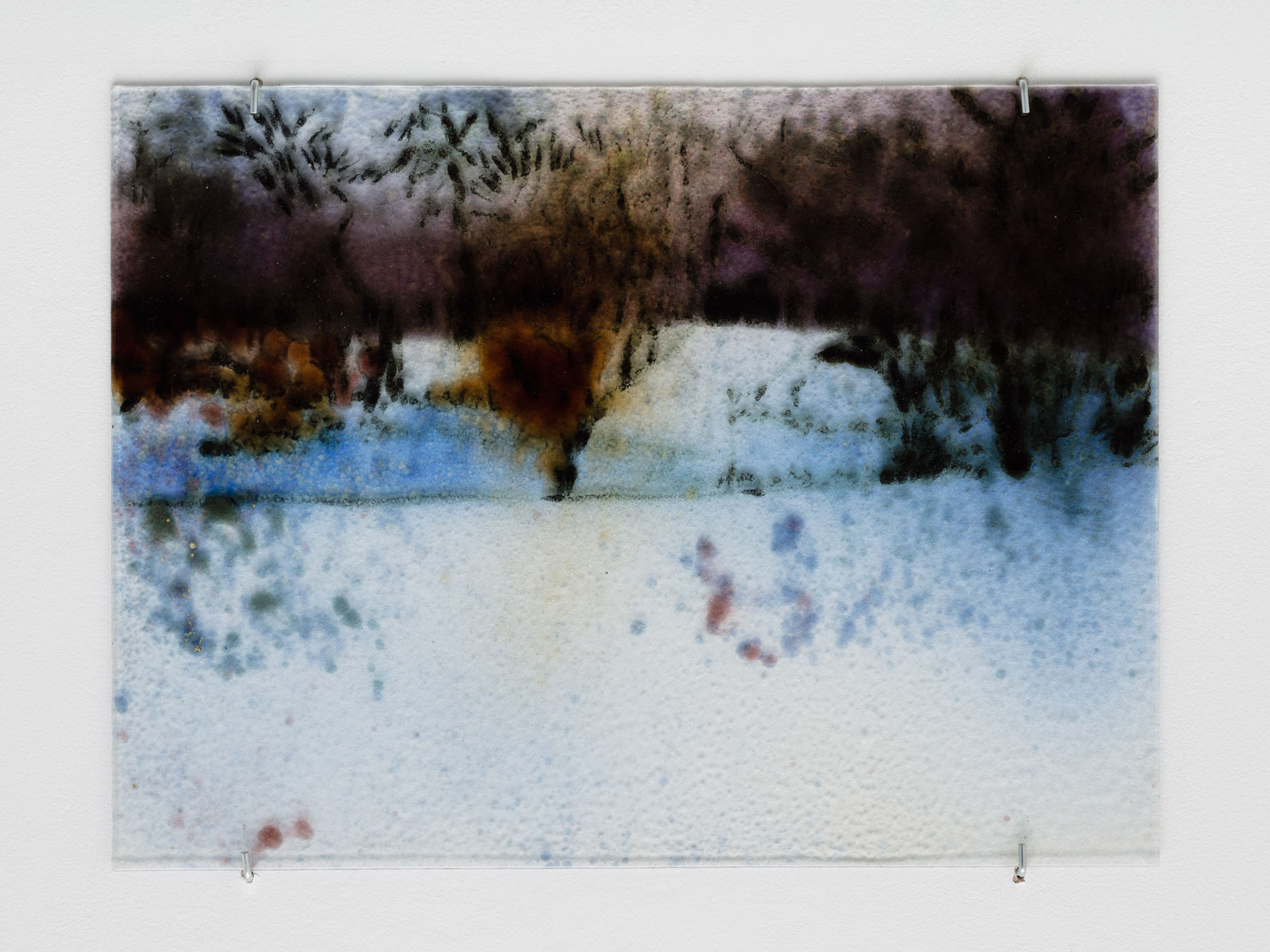

In addition to the frost-filled presentation in Emalin’s exhi-bition space, Serapinas also produced a series of painted glass objects, on view in the gallery’s office, that function alongside the snowmen. Each piece portrays a landscape set within his native Lithuania during wintertime, and according to the artist, depict the various locations from which the motley crew of snowmen and accompanying snow items were sourced. With these works, Sera-pinas excels in navigating the divide between context and narrative: although (we assume) that the images on the glass are of existing places, they are also veritably picturesque, reminiscent of illustra-tions in a storybook, taking on an otherworldly quality, and leaving one with ample space to project one’s own narrative.

When I asked Serapinas about these drawings in relation to the project overall, he replied that it was important for the audience to understand that the snowmen “are coming from so-mewhere.” Listening to the recording of our exchange, I notice he repeats this phrase several times. Such insistence upon this theme of individual histories refers back to the humanisation of the art object (in this instance, imputing the snowmen with a background). More importantly, Serapinas’ emphasis upon acknowledging that these hominal forms “are coming from somewhere” stems from the artist’s emphasis on the intimate and personal.

“From my perspective, it could be nice,” Serapinas remar-ked when discussing the children’s potential reaction to the missing figures, “because maybe they thought that the snowmen walked away.” Only a child would suggest or believe such a fantastical explanation for the snowmen’s disappearance, and for most people, recognising that fact in adulthood inevitably provokes a longing for one’s days of innocence and seeming simplicity. The artist’s deft employment of nostalgia as a tool for connecting the audience to both a commonality with fellow humans and to their individual selves speaks to the gravitas and tenderness at the crux of the installation; like falling in love, the story of one’s childhood is a painfully personal yet highly common experience that constitutes the human experience at large. As such, in keeping with Kristeva’s theory, Serapinas’ snowmen are less a sculptural installation than a means of effectuating communication, both with other “beings“ as well as one’s own self.

Augustas Serapinas, February 13th, 2019, exhibition view, Emalin, London

Augustas Serapinas, February 13th, 2019, exhibition view, Emalin, London

Augustas Serapinas, February 13th, 2019, exhibition view, Emalin, London

Augustas Serapinas, February 13th, 2019, snowmen and snow from Lithuania, dimensions variable

Augustas Serapinas, February 13th, 2019, exhibition view, Emalin, London

Augustas Serapinas, February 13th, 2019, exhibition view, Emalin, London

Augustas Serapinas, February 13th, 2019, exhibition view, Emalin, London

Augustas Serapinas, February 13th, 2019, exhibition view, Emalin, London

Augustas Serapinas, February 13th, 2019, exhibition view, Emalin, London

Augustas Serapinas, February 13th, 2019, exhibition view, Emalin, London

Augustas Serapinas, February 13th, 2019, exhibition view, Emalin, London

Augustas Serapinas, February 13th (1,2,3,9), 2019, each stained glass, 31.5 × 42 cm

Augustas Serapinas, February 13th (1), 2019, stained glass, 31.5 × 42 cm

Augustas Serapinas, February 13th (2), 2019, stained glass, 31.5 × 42 cm

Augustas Serapinas, February 13th (9), 2019, stained glass 31.5 × 42 cm