Artists: Frédéric Bruly Bouabré and Serge Attukwei Clottey

Venue: Burning in Water, New York, US

Date: May 2 – July 17, 2017

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Burning in Water, New York

Burning in Water is pleased to present Frédéric Bruly Bouabré & Serge Attukwei Clottey. The exhibition pairs drawings by the late Ivorian artist Frédéric Bruly Bouabré (1923 —2014) with recent sculptures by the Ghanian artist Serge Attukwei Clottey (b.1985). Although separated in age by over 60 years, both artists employ prosaic materials to develop distinct visual languages. In the works on view, traditional and regionally-specific West African motifs are harmoniously juxtaposed with symbols and texts that represent both the global and the the universal. The unique lexicons developed by both Bouabré and Clottey reveal dually systemic methodologies of materiality and language to investigate a broad array of subjects including the historical, spiritual and political.

Bouabré and Clottey shared an affinity for producing highly iterative series of works that employ the repetitive use of material and form with incremental variation to construct intricate dialogues that are simultaneously expansive and highly-nuanced. The two artists also both integrated semantics into their work, parsing and recombining words and characters from disparate languages to introduce additional dimensions of meaning.

Born in Zépréguhé, a region of French Colonial West Africa, Frédéric Bruly Bouabré became one of the first individuals from the region to learn French and was trained by the colonial government to work as an administrator. Prior to his passing in 2014 at the age of 91, Bouabré spent decades working as a civil servant in Senegal and the Ivory Coast. Over this period, Bouabré developed his own style of drawing, typically utilizing card stock that was widely available in government offices.

In 1948, Bouabré had a revelatory spiritual experience that he described as a “magnificent sunlit vision.” He adopted an additional name, Cheik Nadro (The Revealer), and his drawings became infused with spiritual and religious themes. Bouabré began to employ his artwork as a means of philosophical, historical and spiritual inquiry. Thereafter, he used his drawings, frequently created as large series with common visual elements, as a method of investigating an astonishing array of topics, including regional African history, the role of Africa in the global political and economic system, astronomy, folklore and indigenous religious and cultural practices.

Bouabré created a number of large series of drawings addressing specific topics, such as the Museum of African Faces, which resides in the permanent collection of the Tate in London. Among his most ambitious series was a study of semantics in which the artist laboriously attempted to translate the oral tradition of his own ethnic group, the Bété, into a written, linguistic system. Through over 1000 drawings that combined glyphic representation and text, Bouabré elaborated a syllabary of the Bété language utilizing 448 pictograms corresponding to phonemes.

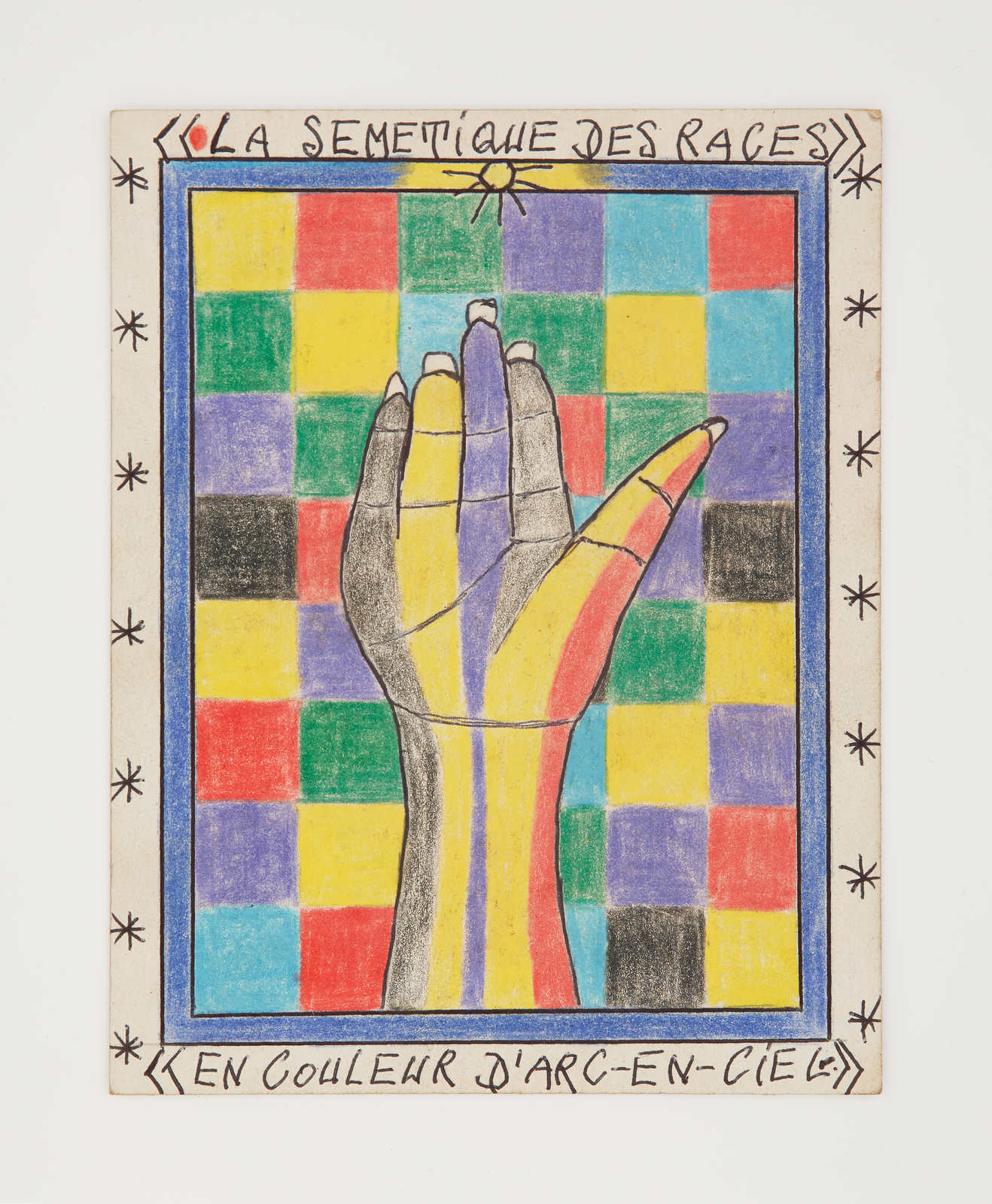

The current exhibition features drawings from three distinctly representative bodies of work: Celeste Lune (Celeste Moon), L’Homme Suspendu Par Les Couleurs (The Man Suspended by Colors) and La Semantique des Races (The Semantics of Race). In keeping with his expansive spiritual and philosophical approach that stressed universal inter-connectivity, Bouabré termed his later drawings to be part of an overarching body of work entitled World Knowledge. The individual and iterative series serves as granular elements that when viewed en masse, form a vastly intricate ontological system. Bouabré’s approach collapses a range of seemingly dichotomous categories: mystic vs. empirical; pictographic vs. semantic; traditional vs. modern; specific vs. universal; epistemological vs. descriptive.

Born in Accra, Ghana several generations after Bouabré, Serge Attukwei Clottey shares with his predecessor an affinity for utilizing modest, common materials to create probing artworks. Employing what he terms the “powerful agency of everyday objects,” Clottey also uses historical and traditional elements to create artworks that are grounded in a spirit of broad inquiry. Where Bouabré tended to focus on spiritual, linguistic and philosophical subjects, Clottey’s work pivots more towards socio-political concerns. Both artists, however, strongly maintain practices that, at their crux, have an overriding concern with the explication of complex systems. In the works on view, Clottey articulates an array of themes that include global trade and inequity, resource allocation, international migration, political corruption and collective memory.

Clottey spent four years studying painting in Ghana, where the curricular materials were mostly old art history textbooks that exclusively addressed the European painting tradition. A fellowship in Brazil introduced him to highly divergent approaches to materiality, abstraction and representation. A subsequent introduction to the work of fellow Ghanian artist El Anatsui inspired Clottey to employ prosaic materials to create artworks that evoke traditional West African forms while simultaneously confronting current global economic and political concerns.

Although he works in an array of modalities including performance, sculpture, installation and photography, Clottey consistently uses shards of plastic shorn from the “jerrycans” that are ubiquitous throughout Accra as a material. These plastic containers are used to import industrial materials such as cooking oil into Ghana, most commonly from China. In Ghana, the cans are re-used for other purposes, principally storing and transporting water. Clottey has used plastic from these containers, which are also known “Kufuor Gallons” in reference to the former president who presided over Ghana’s slide towards water scarcity, as his indexical material for 15 years. Clottey terms his approach in the corpus of work as “Afrogallonism.”

With regard to subject matter, Afrogallonism’s primary tier of reference is to issues surrounding access to suitably potable water as a requisite factor for community health and development. The prevalence of the jerrycan in Ghana is illustrative of the widespread scarcity of safe water. Having been initially used to transport oil or other chemicals, the jerrycans are actually not suitable for storing drinking water. The jerrycans thus imply the threats of environmental degradation and toxicity. Moreover, their sheer number poses a larger environmental problem due to the need for mass disposal. The symbolism of the jerrycans therefore alludes to a paradoxical quagmire of globalism, whereby nations like Ghana are simultaneously constricted by both resource scarcity and the toxic ramifications of industrial over-production.

In his Afrogallonism works, Clottey has re-iterated the use of jerrycan plastic in a myriad ways, including large-scale performances mounted on the streets of Accra by the performance collective GoLokal, which Clottey founded. The current exhibition features four examples of Clottey’s wall sculptures, which hang like textiles or tapestries. The reference to textiles is reinforced by the patterning of the plastic tiles and hand-painted elements, but the plastic segments retain indelible signs of ware and usage. The visual reference to Dutch wax textiles evokes issues of mercantilism, cultural appropriation and gender identity, with the later theme poignantly addressed in Clottey’s acclaimed performance piece My Mother’s Wardrobe.

Clottey’s engagement with trade points to the artist’s own personal and familial history in addition to the broader topics associated with globalism, as trade has been an intrinsic element in the historical identity of the Clottey clan. The artist’s ancestors traded meat and alcohol which they imported into the coastal region of Labadi via sea. A large sign in the artist’s studio features the name of his great-great-grandfather who developed the family’s coastal trade, Nii Tetteh Nteni. In the local Ga language, Nteni translates to “liquor,” and in later years the family transported alcohol for trade in yellow jerrycans.

Fragments of text and characters in multiple languages are painted onto the the plastic tiles of the Afrogallonism wall sculptures. Chinese characters allude to the origin of the jerrrycans, while the diversity of languages situates the work within the context of international trade and globalism. The abbreviated textual elements and symbols also function enigmatically; suggesting encoded or disrupted messages.

As elaborated by Clottey, Afrogallonism simultaneously employs multiple viewpoints: historical, descriptive and proscriptive. Conceptually, Clottey’s concept of Afrogallonism is congruent with the broader tenets of Afrofuturism, wherein water — particularly as regards its availability and pureness — is a key recurring theme. The artist views his treatment of the subject as not only illustrative but also provocative: “Afrogallonism is about pushing back to the West what they left behind.”

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré (b. circa 1923, Zépréguhé, West Africa; d. 28 January 2014, Abidjan, Ivory Coast). A pioneering West African artist, Frédéric Bruly Bouabré created a series of drawings reflecting over a half century. Bouabré’s work first gained widespread international attention in the seminal Magiciens de la Terre exhibition staged at the Centre Georges Pompidou and Grande halle de la Villette in Paris in 1989. In 1992, his work was featured in the Out of Africa show exhibition by the Saatchi Gallery in London, and subsequently presented at the 1993 Venice Biennale. A two-artist show featuring Bourabré’s work alongside that of Italian artist Alighiero Boetti was featured at the DIA Center for the Arts in New York and the American Center in Paris in 1993. Major solo exhibitions of Bouabré’s work have been mounted by the Ikon Gallery in the UK and the Musée Champollion in France. The artist’s Museum of African Faces series is in the permanent collection of the Tate Modern. Bouabré was again featured in the Venice Biennale in 2013.

Serge Attukwei Clottey (b. 1985, Accra, Ghana) lives and works in Accra, Ghana. Clottey earned a diploma in fine arts from the Ghanatta College of Art and Design in Ghana and has completed multiple fellowships abroad. He currently works in a variety of media including performance, photography and sculpture. For the past 15 years, he has produced his Afrogallonism series. His performance piece My Mother’s Wardrobe was the inaugural show at Ghana’s first contemporary art space, Gallery 1957. His work has been exhibited at Kampnagel Hamburg (Hamburg); The Mistake Room (Los Angeles); University of Museum of Contemporary Art (Amherst, MA) and the Goethe Institute and Alliance Francais (Accra).

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Untitled, 2008, Ballpoint and colored pencils on cardstock, 9 × 6 1/4 in, 22.9 × 15.9 cm

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Untitled (Une Charitable Main 1), 2000, Ballpoint and colored pencils on cardstock, 7 1/2 × 6 in, 19.1 × 15.2 cm

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Untitled (Une Charitable Main 2), 2000, Ballpoint and colored pencils on cardstock, 7 1/2 × 6 in, 19.1 × 15.2 cm

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Untitled (Une Charitable Main 7), 2000, Ballpoint and colored pencils on cardstock, 7 1/2 × 6 in, 19.1 × 15.2 cm

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Untitled (La Sémantique des Races), 2000, Ballpoint and colored pencils on cardstock, 7 1/2 × 6 in, 19.1 × 15.2 cm

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Untitled (L’homme Suspendu XXI), 2011, Ballpoint and colored pencil on cardstock, 7 1/2 × 6 9/10 in, 19.1 × 17.5 cm

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Untitled (L’homme Suspendu XXIII), 2011, Ballpoint and colored pencil on cardstock, 7 1/2 × 5 9/10 in, 19.1 × 15 cm

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Untitled (L’homme Suspendu XXVI), 2011, Ballpoint and colored pencil on cardstock, 7 1/2 × 5 9/10 in, 19.1 × 15 cm

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Untitled (Celeste Lune/Egyptiens), 2012, Ballpoint and colored pencil on cardstock, 7 1/2 × 5 22/25 in, 19.1 × 14.9 cm

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Untitled (Celeste Lune/Burkinais), 2012, Ballpoint and colored pencil on cardstock, 7 1/2 × 5 22/25 in, 19.1 × 14.9 cm

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Untitled (Celeste Lune/Americains), 2012, Ballpoint and colored pencil on cardstock, 7 1/2 × 5 22/25 in, 19.1 × 14.9 cm

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Untitled (Celeste Lune/Japonais), 2012, Ballpoint and colored pencil on cardstock, 7 1/2 × 5 22/25 in, 19.1 × 14.9 cm

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Untitled (Celeste Lune/Syriens), 2012, Ballpoint and colored pencil on cardstock, 7 1/2 × 5 22/25 in, 19.1 × 14.9 cm

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Untitled (Celeste Lune/Bresiliens), 2012, Ballpoint and colored pencil on cardstock, 7 1/2 × 5 22/25 in, 19.1 × 14.9 cm

Serge Attukwei Clottey, The Night Before, 2016, Plastics, wire and oil paint, 41 × 26 in, 104.1 × 66 cm

Serge Attukwei Clottey, Fades Chinese Print, 2016, Plastics, wire and oil paint, 30 × 38 in, 76.2 × 96.5 cm

Serge Attukwei Clottey, Outdooring day, 2016, Plastics, wire and oil paint, 22 × 22 in, 55.9 × 55.9 cm