What the Olive Branch Has Seen

Curated by Àngels Miralda

Verde que te quiero verde

Verde viento, verdes ramas.

El barco sobre la mar

Y el caballo en la montaña

Green, how I want you green.

Green wind. Green branches.

The ship out on the sea

and the horse on the mountain.

–Federico García Lorca

An eternal conversation blows through the olive branches of doubled landscapes[1]. Across the knobbed bark of grandmother’s hands, leaves like sharp fingers shading a ripening fruit. Every September, bitter and hard, little black diamonds melt into gold. With a lifespan of thousands of years – trees have drunk centuries of carefully watered soil. Planted and tended by ancestors whose names we no longer remember, but who still play with your hair in the autumn breeze. A symbol of peace – they say – and one who cannot move, cannot be displaced, cannot but stand still and be.

The village where my great-grandfather was born is in the hills that overlook Cartagena, where the sweetest oranges fall into the salted sea. Out of the yellow earth scorched by sun and the fine Saharan sand; almonds, carob, strawberry, grape, fig, and olive. Yellow summers, and green winters spark a power of recognition, presence, and distance.

More than 800,000 olive trees have been uprooted by Israeli forces following the massacres and forced expulsion of the Palestinian people since 1948[2]. It is said that Al-Badawi, an olive tree that lives near Bethlehem, is 4,000 years old[3]. These trees have become a symbol of the peace and resistance of the Palestinian people who risk continuous attacks from illegal settlers in order to save their harvests. Time does not heal but increases the intensity of destruction including the severity of the events in 2023[4]. The trees are an extension of the land and its people, they anchor communities to soil, making them physical and symbolic targets for annihilation. Farmers regularly find that their trees have been uprooted, burned, stolen, or vandalised[5].

Environmental degradation is not a symptom, but policy[6]. The importation of foreign pine trees by the Israeli state caused acidification of the soil. In turn, desertification took hold in an already arid region. The walls built to stop human movement also restrict the natural migration paths of animals who carry pollen and seeds, now cut off from access to their feeding grounds[7]. We also form part of a symbiotic network of soil, seeds, and livestock in which artificial political boundaries play no part. Jumana Manna’s film Foragers follows the Palestinian elders who are patrolled, controlled, and stopped from clipping wild plants, a continuous practice of cohabitation of territory since Neolithic times that promotes the healthy growth of edible and medicinal plant life[8].

Some of the state-sanctioned uprooting has been done for the purpose of building new roads to connect illegal settlements[9]. These roads serve to cut access further between villages as well as farmers from their orchards. New impositions of farming methods include monoculture techniques rather than a mixture of orchards, foraging, and mixed crops that work in tandem with the soil for renewal of nutrients and disease-resistance[10]. Shells and bombs that do not hit infrastructure still lead to long-term consequences for life in affected areas. It is unknown what contaminants and chemicals are inside of Israeli and American weapons, some compounds such as white phosphorus produce multi-front forest fires and seep into groundwater[11].

Parallels in our landscapes have always been found. In 1963 Pier Paolo Pasolini visited Palestine with the hope of finding filming locations for Il Vangelo Secondo Matteo (1964). The film was ultimately filmed in Southern Italy – a parallel landscape with geological and aesthetic similitude. Pasolini lamented that the Israeli settlements resembled the new suburbs of Rome, while the occupation marked the Palestinians with misery[12]. No matter the angle of the camera, it was unable to avoid scenes that testified to the militarised borders and omnipresence of colonial capitalism[13].

One of the recurring references in the work of Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish is Federico García Lorca[14]. Both poets wrote of the deep bonds between people and their landscapes while speaking of injustice and political repression. Lorca actively fought against the historical erasure of Arabs in the Iberian peninsula through references to the prose of Andalusi authors[15]. Darwish, a refugee since childhood, yearned for Al-Birwa – his place of birth that existed only in his memory.

In opposition to Pasolini’s “heretical orientalism”[16] it is possible to find Palestine under the shade of an olive tree as a symbol calling out for anti-colonial internationalism. Rather than searching for landscapes untouched by the scars of omnipresent occupation, it is possible to feel the trees shake due to distant vibrations and the ghosts of checkpoints under the sun’s rays. This landscape belongs to all seeds that drift in the wind and thrive in this climate, a shared recollection of familiarity summoned by closed eyes imagining something called home. Images, archives, and histories emerge from the interconnected region between Central Asia, Southern Europe, and North Africa. History flows outside of pacted borders and artificial segregations, whose hands are busy with the same action of picking, gathering, pickling, pressing.

لو يذكر الزيتون غارسهُ

لصار الزيت دمعا!

If the olive trees knew the hands that planted them

Their oil would become tears.

–Mahmoud Darwish

Notes:

[1] Thank you to my neighbour Aida Qasim for the conversation about Darwish and Lorca.

[2] Raja Shehadeh, “The Uprooting of Life in Gaza and the West Bank,” 26 October 2023. The New Yorker. Link

[3] Noor Ibrahim, “Olive Groves in the West Bank Have Become a Battleground. That’s Why Volunteers Come From Around the World to Help at Harvest Time” Time, 1 November 2019. Link

[4] Bárbara Ayuso, “Los últimos palestinos que resisten en el olivar: “Los colonos tratan de quitarnos la comida sobre la mesa”” 17 November 2023. Link

[5] Amira Hass, “5,000 Trees Vandalized in Palestinian West Bank Villages in Less Than Five Months” Haaretz, 10 May 2023. Link

[6] Mazin B. Qumsiyeh and Mohammed A. Abusarhan, “An Environmental Nakba: The Palestinian Environment Under Israeli Colonization”, Science Under Occupation, Volume 23. Spring 2020. Link

[7] Vanessa O’Brien, “Animal migration,” 11 February 2012. Link

[8] Jumana Manna, “Where Nature Ends and Settlement Begins” E-Flux Journal, November 2020. Link

[9] The Israeli Information Centre for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, “Some 1,000 Olive Trees Uprooted to Build Bypass Road on Azzun Village Land” 5 February 2017. Link

[10] Carolina S. Pedrazzi, “In the West Bank, Israeli Settlers are Burning Palestinians’ Olive Trees” Jacobin. 11 October 2023. Link

[11] Middle East Monitor, “Report on Long-term Effects of Israeli White Phosphorous,” 20 February 2014. Link

[12] SouthSouth, “Pasolini Filming Palestine,” 15 April 2010. Link

[13] “The shots of Jerusalem surrounded by barbed wire are particularly compelling. As Pasolini’s voiceover expresses awe at the natural beauty of these surroundings, the camerawork displays the indignities of everyday life for Palestinian inhabitants. As seen above, the camera zooms in and out of a shot of birds perched on top of barbed wire, in and out and in and out, a syntactical repetition of a sublime and sordid reality.” ibid.

[14] Mahmoud Darwish, Unfortunately, it was Paradise, University of California Press. 2003. (pg. Xvi Introduction) The first citation of the book are Lorca ‘s phrases “pero yo ya no soy yo / ni mi casa es ya mi casa).

[15] “In the Shadow of Lorca” (https://www.latinolife.co.uk/articles/shadow-lorca) Including 12th century poet Ibn Khafaja’s poetry about the fall of Valencia.

[16] Luca Caminati, “Orientalismo eretico: Pier Paolo Pasolini e il cinema del Terzo Mondo” Bruno Mondadori. 2007.

January 17 – February 7, 2024

Inas Halabi

We Have Always Known the Wind’s Direction, 2019-2020

HD video and sound, single screen, Arabic with English subtitles, 11:57 min

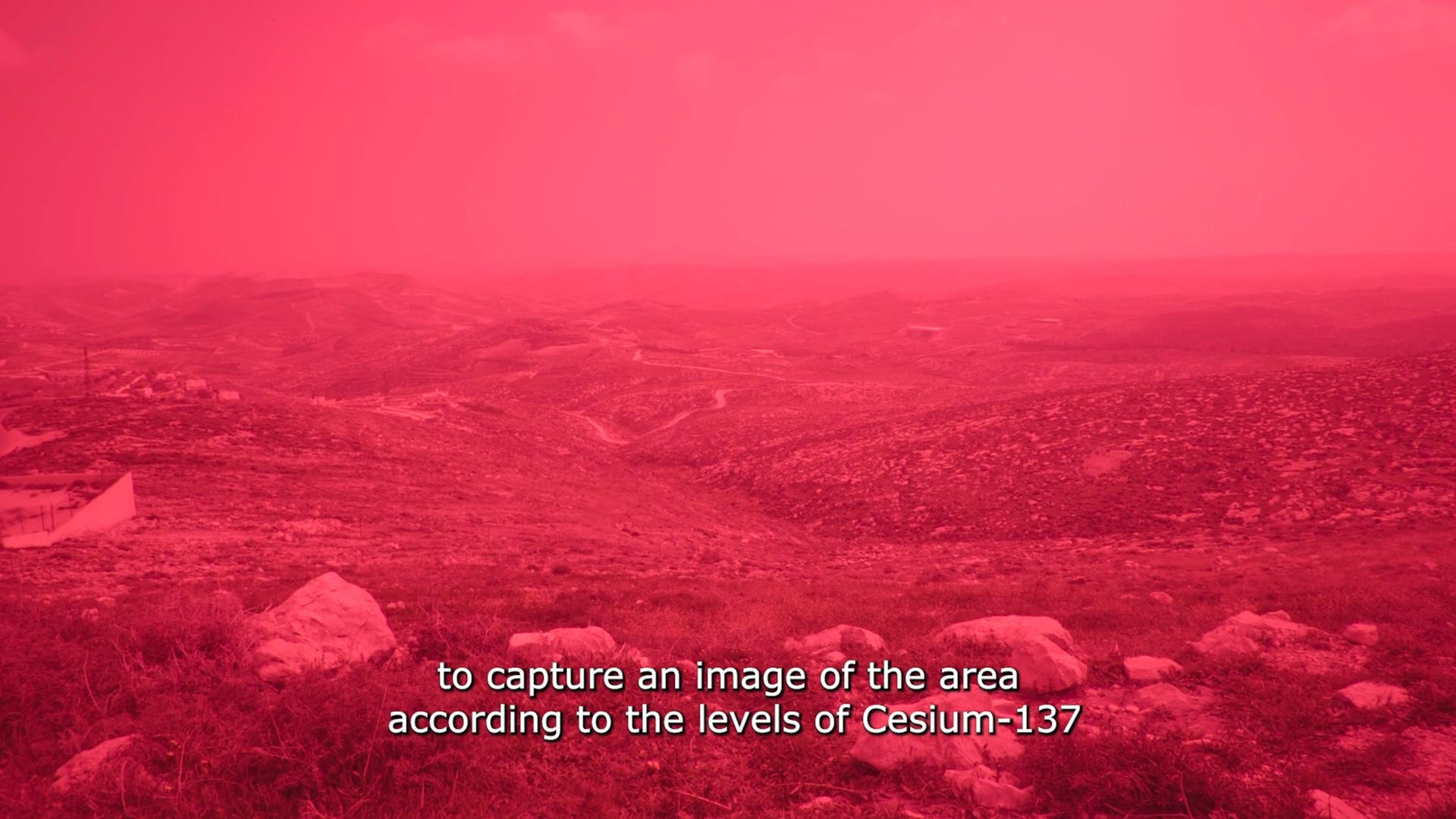

Since the 1960’s, records exist about the state of Israel’s purchases of nuclear equipment and experiments, yet, it has never clarified its nuclear capacities[1]. Dimona is a secret facility just south of the West Bank city of Hebron. At this station, illegally imported material has been used and atomic tests carried out without the necessary international inspections[2]. Before the extent of health problems from nuclear material was known, Israeli espionage and theft of materials took place on US soil[3]. To this day, these actions are met with total impunity by the international community. Due to the presence of multiple radioactive isotopes around the city of Hebron and other areas in the West Bank, it is believed that nuclear waste and other toxic bio-hazardous materials have been dumped for years into Palestinian territory[4].

In 2021, Palestinian Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayye called for a probe into waste sites of electronic and nuclear material as noticeable adverse health effects had been noted in nearby populations[5]. No conclusions have been reached from this probe, and Israel continues to restrict access to international committees[6]. According to Dr. Mahmoud Saadah, the only places in the world with higher concentrations of Cesium-137 than the Palestinian West Bank are Chernobyl and Fukushima.

Inas Halabi’s We Have Always Known the Wind’s Direction (2019-2020) is a filmic investigation into the people and landscape swathed in lethal uncertainty. Although it is not possible to confirm the location or contents of Israeli dump-sites, it is possible to detect the levels of toxic compounds such as Cesium-137 at various sites. Together with Dr. Khalil Thabayneh, Inas Halabi travels over the landscapes of Palestine’s West Bank adding red filters to the camera to reflect the detected levels of the poisonous compound. The film’s focus on an invisible subject reflects on the notion of invisibility and the systemic network of power and control in the region. The film constructs a methodology for addressing the un-filmable but imperative necessity to document the human and environmental catastrophe unleashed in the region.

Inas Halabi (b.1988, Palestine) is a visual artist and filmmaker. Her practice is concerned with how social and political forms of power are manifested and the impact that overlooked or suppressed histories have on contemporary life. She holds an MFA from Goldsmiths College in London and completed the De Ateliers artist residency in 2019. Recent exhibitions and screenings include Hot Docs Film Festival, Toronto (2023), de Appel, Amsterdam (2023), Showroom London (2022), Europalia Festival, Brussels (2021), Silent Green Betonhalle, Berlin (2021); Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (2020); and Film at Lincoln Center, USA (2020). She lives and works between Palestine and the Netherlands.

Àngels Miralda (1990) is an independent writer and curator. Her recent exhibitions have taken place at Something Else III (Cairo Biennale); Garage Art Space (Nicosia); Radius CCA (Delft), Tallinn Art Hall (Estonia), MGLC – International Centre for Graphic Arts (Ljubljana), De Appel (Amsterdam), Galerija Miroslav Kraljevic (Municipal Gallery of Zagreb), the Museum of Contemporary Art of Chile (Santiago), Museu de Angra do Heroísmo (Terceira – Azores), and the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art (Riga). Miralda wrote for Artforum from 2019-2023 and regularly publishes with Terremoto (Mexico City), A*Desk (Barcelona), Arts of the Working Class (Berlin), and is editor-in-chief of Collecteurs (New York).

Notes:

[1] Julian Borger, “The truth about Israel’s secret nuclear arsenal,” The Guardian, 15 January, 2014. Link

[2] “Israel refused to countenance visits by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), so in the early 1960s President Kennedy demanded they accept American inspectors. US physicists were dispatched to Dimona but were given the run-around from the start. Visits were never twice-yearly as had been agreed with Kennedy and were subject to repeated postponements.” ibid.

[3] Scott C. Johnson, “What Lies Beneath,” Foreign Policy, 23 March 2015. Link

[4] POICA, “Report about Nuclear Radiation in South Hebron” 3 October 2008. Link

[5] The Cradle, “Palestinian PM urges probe into Israel’s improper disposal of toxic waste in the West Bank,” 8 December 2021. Link

[6] Anas Abu Arqoub, “Is waste from Israel’s nuclear programme poisoning Palestinians?.” The New Arab, 30 June 2015. Link

Inas Halabi, ‘We Have Always Known the Wind’s Direction’, 2019-2020. Film still. 11:57 min, Courtesy of the artist

Inas Halabi, ‘We Have Always Known the Wind’s Direction’, 2019-2020. Film still. 11:57 min, Courtesy of the artist

Inas Halabi, ‘We Have Always Known the Wind’s Direction’, 2019-2020. Film still. 11:57 min, Courtesy of the artist

Inas Halabi, ‘We Have Always Known the Wind’s Direction’, 2019-2020. Film still. 11:57 min, Courtesy of the artist