Artists: Michael Van den Abeele, Ruth Angel Edwards, Gretchen Lawrence, Lulou Margarine, Dani & Sheilah ReStack

Exhibition title: Slow Dance (2)

Curated by: Luca Beeler & Richard Sides

Venue: Stadtgalerie Bern, Bern, Switzerland

Date: April 8 – May 6, 2023

Photography: Studio Mussano / all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Stadtgalerie, Bern

Slow Dance is composed of sixteen scenes, consisting of four different rooms in four exhibitions over a period of six months. During this time, the exhibition spaces remain structured by two walls, each with a functioning door. Instead of providing an overview, they offer passages. Slow Dance could describe the attitudes of a person in conversation as they attempt to provoke reactions in other people. Here, what slowly comes into focus is the political implications of subliminal choreography.

Slow Dance (2) grows out of an ongoing conversation around the convergence between the specificities of exhibition making and installation. The artworks and objects cohabiting within the structure of the exhibition form an interconnected logic that mirrors living in constant relationship with various active temporalities and timescales. How we encounter the material world is at once a form of compromise whilst simultaneously an experience of precarious accumulation. Scale, growth and history confuse our sense of ideology. Organic rhythms zoom out from media realities.

A chicken crosses the street and walks over to me. It tells me that dinosaurs never really died. It’s an old chicken, I can clearly see that. I can see the age around its beady eyes. “Look closely at my legs,” the chicken says. “my three toes, look at the skin, the leather. Don’t you recognize it? Dinosaurs never died – the chicken says – we just grew smaller and smaller, until insignificant like everything that gets older. But it’s OK, there’s no need for drama. you don’t need to dig or look for a better hidden truth or meaning, or bones -let alone to bring those bones back to life… no need to bring dinosaurs back to life because… we never really died, did we”… The chicken looks around, as if to show and assure me that it is a part of this world, standing in it, here and now. “We just slowly evolved”, the chicken continues, “into something more modest and feathered and maybe less favorable -But we never died.” Besides age I can see kindness in its eyes. I look for a voice that isn’t too hurtful or arrogant, and I tell the chicken that I don’t care about any of that. “You do not matter” I tell the chicken. “Look around you. Look at all the misery, can you do that- people are not happy, they suffer, and your tale, your personal biology, it doesn’t bring hope, it doesn’t inspire. The thing that does actually matter, the only thing of interest, is the resurrected dinosaur. I am glad we met, now I can forget you.” Michael Van den Abeele, 2021

Recording interactions and activities from the viewpoint of a first person perspective alludes to playing video games. In recent times (through the popularity of the GoPro and wide-angle consumer cameras) the internet has flourished with content shot this way: extreme sports, banal daily activities, urban explorations and car dashcam sightings of meteors entering the Earth’s atmosphere. Could it be only a matter of time before technology can see into the human brain to record sensory input as transactional experiences?

“Strange Days”

In the 1970’s, the artist Margaret Raspé made a helmet which allowed her to attach a camera to her head and record from her line of sight during various domestic activities. Similarly – but from a different kind of domestic situation, the lockdown in London (enforced during Covid-19) – RUTH ANGEL EDWARDS made the video Trip in Me (2020) as a reflection on urban malfunction and daily routine. Soundtracked by her own DJ mix of Drum & Bass, mashups and mechanical sounds. The video develops from a “line of sight” perspective, starting with morning routine; showering, eating breakfast on the roof of her home and deciding on what outfit to wear, all before venturing to the streets where she pulls wheelies through Central London as part of a bicycle gang. A remixed version of J-Lo’s Waiting for Tonight heightens the activities as it becomes clear this is found footage cleverly spliced as the daring protagonist actually wears the same black coat as Edwards. “Don’t liberate me, I’ll take care of that”.

After running several red lights the cyclist dismounts and visits a friend who has access to a roof in Central London. They change into skater clothes and have a cup of tea. She pets the dog. The music breaks down temporarily (we are back in Edwards’ head) before kicking in once again with Seeka’s Dialogue as she runs off the edge of the roof, clambering over metal air ventilation systems and decommissioned chimneys. Once again, the suspension of disbelief lags until it becomes clear the parkour experts are urban edgelords who upload their activities to youtube/twitch/you-name-it. The video functions as an alchemical realisation of a desire to escape or to take a trip, offering up residual material of the experience for others to watch.

Spirals are active and wind outwards from a single point as a continuous curve. They can be found in nature; usually the most desirable fossils are spirals. The central part of a spiral is a sort-of vortex. Whirlpools and tornadoes propel themselves as spiralling energy. People project different moods onto spirals, they are psychedelic and mystical, and they can be conceptualised as either going up or down. The Downward Spiral is an iconic album by Nine Inch Nails and could be read as the epitome of existential dread. Trent Reznor, the creator of Nine Inch Nails, famously recorded the 1994 album in the house in which Sharon Tate was murdered by the Manson Family. He later disclosed that he regretted buying the house and felt it was insensitive to exploit her death as a drive for his doomy creativity. In conceptual art history Robert Smithson’s earthwork, Spiral Jetty (1970), is one the most notable artworks to use the shape. Installed “permanently”, but vulnerable to change by way of water levels, the intervention deals with an elemental timescale and looks at the world outside of human experience.

GRETCHEN LAWRENCE’s spiral, My Spiral (2022), fills the room with her geometry. The walls and the floor are utilised as planes onto which black paint is applied to create a large-scale spatial installation. Her spiral fills the floor and flips the room’s axis to envelope the walls. Two spaces on the surfaces are developed – black space and white space. This could be thought of as positive and negative space or, that which is and which is not, both coiling and existing simultaneously. Within the installation an assemblage sculpture is also installed, consisting of personal effects, or found objects that loosely associate to lived experience. Here, the crudely named energy drink Pussy is glued to a Jewel cd case and a digital camera. What could be reminisced here is the inventive teenage hedonism when acquiring alcohol was not possible and drinking too much caffeine was the high of the times. Consuming psychology and developing psychology can be sometimes linked when thinking about the teenager.

My Spiral places the onlooker within a spiral, something of a simulation or unexpected experience in the physical world. Something between a dream, or hallucination, and the set of a club in which music videos are filmed.

In 1858 the dinosaur was a relatively new discovery. In this year, the Great Exhibition in Crystal Palace, London displayed renderings of what a dinosaur might look like for the first time; built in clay and cast in cement. Over time an understanding of what dinosaurs looked like has changed and continues to do so; there is no existing visual observation to draw from other than commissioned impressions believed to be realistic.

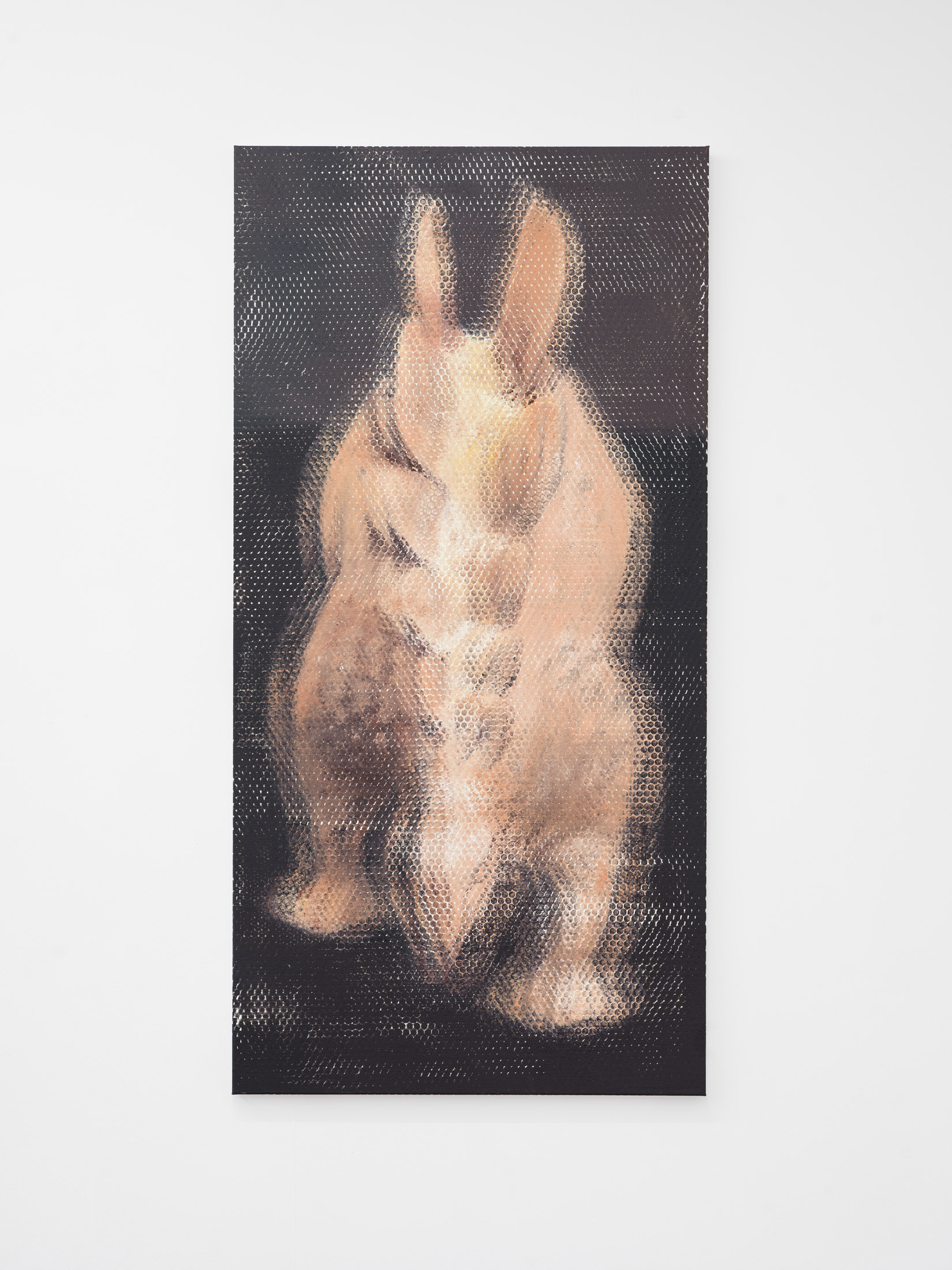

MICHAEL VAN DEN ABEELE thinks about dinosaurs quite often. Since 2014 he has been painting them and in 2017 started to paint them (based on close-up shots of toys) on bubble wrap before grafting onto the canvas, two or three times depending. The painted dinosaurs are transferred during this process, but only what sits on top of the machine-arranged plastic bubbles. Through abstraction the image of creatures emerge as a moiré. The tradition of Op Art is alluded to and a rudimentary form of printing is invented.

In the video trilogy Feral Domestic (2016-2022) by DANI and SHEILAH RESTACK, the camera becomes an intimate, sensory part of the body. Ears underwater, muffled sound penetrates through different bodies. The artists extract a physicality from video that cultural and technological imperatives constantly act upon us to displace. Blood mixes with water. The microphone hits the floor. Strangely Ordinary This Devotion (2017), Come Coyote (2019) and Future From Inside (2022), among others, are about the possibility and impossibility of bringing a life into the world. They’re about magic and climate disaster.

“You just always wanna show these disgusting things, like some sort of perverse desire to gross us out,” Sheilah ReStack says off-screen, as the camera focuses on a white cat with its left bleeding ear hanging down, half torn off. “It’s not to gross us out, it’s reality, which is… gross. I mean I don’t even think it’s gross. I just think it’s… reality is brutal. Why won’t we show it?” retorts Dani ReStack.

A shared artistic practice of relationships and a constant negotiation between different realities is imbued with queer desire, beauty, humour and violence. People, animals and the environment are in multiple relationships of affinity and difference.

Together they form an organic mass of daughter, mother, artist, lover. Their feral domesticity is not an isolated one: pop songs, books they read to each other, films they watch, the women they are in contact with act as avatars for their interactions.

How can one claim that the clock is a cultural achievement, a product of capitalism, when it is so peculiarly linked to planetary movements? Clocks, watches and timers were all the rage during industrialisation. The factories had to produce and adjust to a regular rhythm and the state would follow. Now we have the internet where time feels fractal. The electric oven eclipsed the gas stove in the middle of the 20th century. Now, the domestic oven gets neglected by modern city dwellers and there is no internet connection to regulate and update its discrepancies with the world clock, the smart kitchen is still niché in 2023.

Time of Day (2017) is a photo series by LULOU MARGARINE. The images show the digital time on the display of an oven at various times – at night and during the day. The oven is the site of multiple constraints and controls. It is still there in the kitchen, at all times. The display changes with every minute, and the production of these images requires a rhythm that is asynchronous to leisure time and (unpaid) work structured by capitalism and its clocks. Lulou Margarine seeks it out at any time of day, an uncanny attraction, like the insect attracted to the light on display. The clock runs in sync with the time of day and the level of natural light and describes a disparate state between natural and naturalised time. Domestic space functions as a mirror of the psyche with the far-reaching endeavour to structure time into measurable units.

Slow Dance (2), 2023, installation view, Stadtgalerie Bern

Slow Dance (2), 2023, installation view, Stadtgalerie Bern

Slow Dance (2), 2023, installation view, Stadtgalerie Bern

Slow Dance (2), 2023, installation view, Stadtgalerie Bern

Slow Dance (2), 2023, installation view, Stadtgalerie Bern

Slow Dance (2), 2023, installation view, Stadtgalerie Bern

Michael Van den Abeele, Dinosaur painting #15, 2017, Stadtgalerie Bern

Michael Van den Abeele, Dinosaur painting #17, 2017, Stadtgalerie Bern

Michael Van den Abeele, Dinosaur painting #16, 2017, Stadtgalerie Bern

Michael Van den Abeele, Dinosaur painting #20, 2017, Stadtgalerie Bern

Ruth Angel Edwards, Trip in Me, 2020, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Ruth Angel Edwards, Trip in Me, 2020, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Slow Dance (2), 2023, installation view, Stadtgalerie Bern

Gretchen Lawrence, My Spiral, 2022, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Gretchen Lawrence, My Spiral, 2022, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Gretchen Lawrence, My Spiral, 2022, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Gretchen Lawrence, My Spiral, 2022, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Gretchen Lawrence, My Spiral, 2022, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Gretchen Lawrence, My Spiral, 2022, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Gretchen Lawrence, My Spiral, 2022, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Gretchen Lawrence, My Spiral, 2022, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Lulou Margarine, Time of Day, 2017, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Lulou Margarine, Time of Day, 2017, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Lulou Margarine, Time of Day, 2017, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Lulou Margarine, Time of Day, 2017, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Lulou Margarine, Time of Day, 2017, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Lulou Margarine, Time of Day, 2017, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Lulou Margarine, Time of Day, 2017, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Slow Dance (2), 2023, installation view, Stadtgalerie Bern

Dani & Sheilah ReStack, Come Coyote, 2019, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Dani & Sheilah ReStack, Come Coyote, 2019, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Dani & Sheilah ReStack, Come Coyote, 2019, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Dani & Sheilah ReStack, Come Coyote, 2019, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Dani & Sheilah ReStack, Come Coyote, 2019, Stadtgalerie Bern, installation view

Slow Dance (2), 2023, installation view, Stadtgalerie Bern

Slow Dance (2), 2023, installation view, Stadtgalerie Bern

Slow Dance (2), 2023, installation view, Stadtgalerie Bern

Slow Dance (2), 2023, installation view, Stadtgalerie Bern

Slow Dance (2), 2023, installation view, Stadtgalerie Bern