Artists: Keith Boadwee & Club Paint

Curated by: Smallville

Venue: Smallville Espace d’art contemporain, Neuchâtel, Switzerland

Date: June 7 – 29, 2019

Photography: All images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Smallville

The squeak of rubber on waxed concrete tears Feti away from his endless digressions. The curator mechanically follows the robot’s caterpillar tracks to a room where works are stored under the designation provocative twenty-first century painting. At the entry to the section on the new rebels movement, a box made of giant sequoia wood located next to crates containing the major works of Soufiane Ababri and Andrej Jubravsky is opened by the techni-cal assistant’s multifunctional arm with a few gestures of superhuman precision. In the blink of an eye, its articulated metallic arms, capable of crushing a bodybuilder’s phalanxes with ease, spread twenty or so paintings in various formats by American artist Keith Boadwee out on the ground like frisbees.

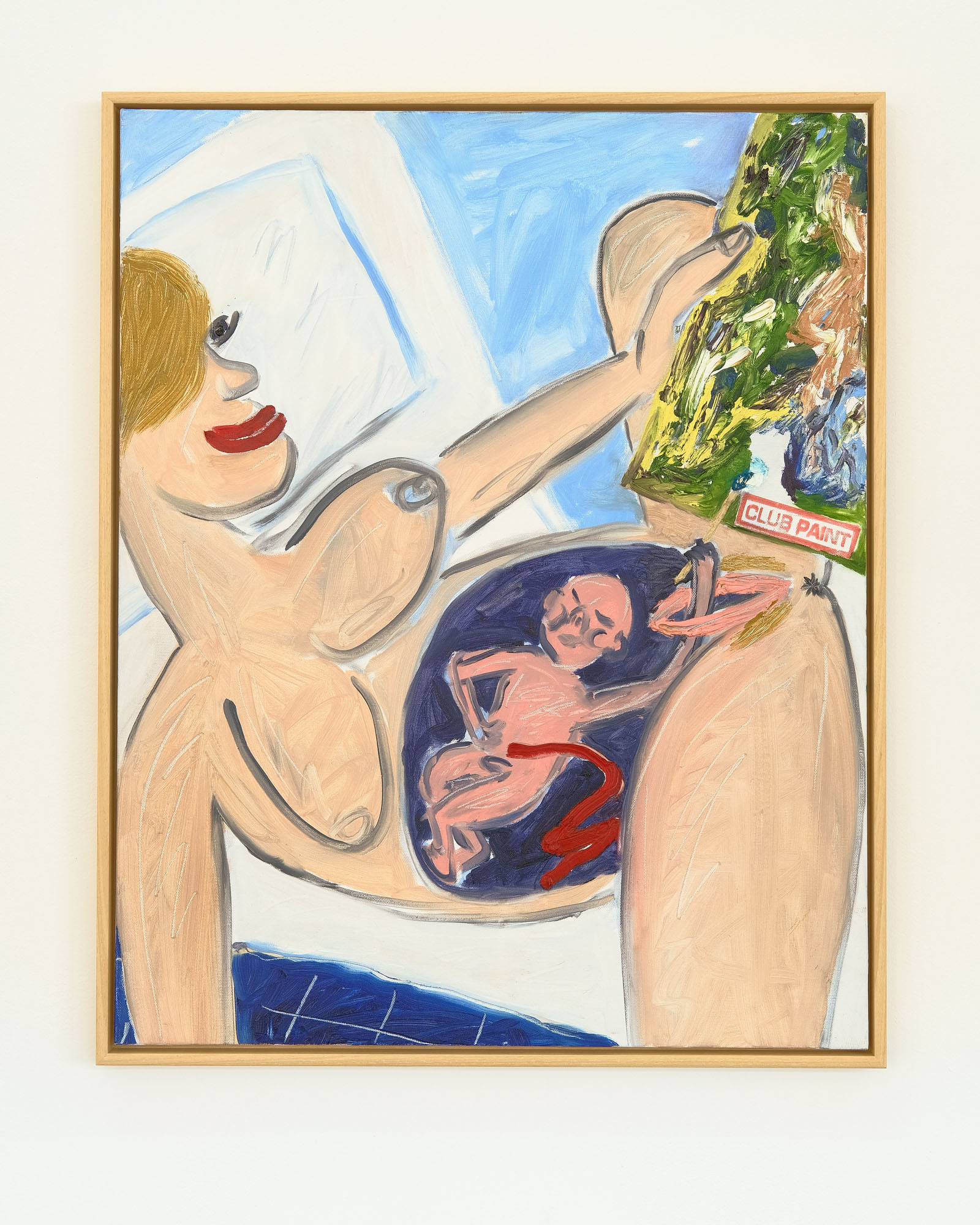

Born in 1961 near a US Navy base in Meridian, Mississippi, Keith Boadwee’s fame began with his “homoerotic” photography work. Considered a master of transgressive art, capable of spraying paint out of his anus far before anyone else and, though fascinated by digestive residue and more largely by wild (to say the least) sexuality, his pictorial work displays fast, confident, nearly virtuosic gestures, with an almost moving, childlike spontaneity.

Feti makes his choice quickly. He opts for completing the annex room with a remarkable me-dium-format painting. It contains a golden, shimmering cyprinid, swimming through the kind of aquarium that has long been illegal and greedily drinking urine that’s happily being projec-ted from a circumcised penis.

For a certain number of specialists, this painting with a blue background is not part of the artist’s personal production but displays the hallmarks of disciples of the legendary group of figurative painters known as CLUB PAINT.

This is of little importance to the curator Ben Salem. It’ll do plenty well to get people talking, even today. He can already see the vultures of the neo-anti-speciesist league, powerful lob-byists within the Union, throw an exasperated fit over it.

It’s the big day, and the acid rain will likely soon give way to the aurora borealis. Brawndo will flow. The much-anticipated opening, which will make a big impression and dominate conver-sations, takes place tonight. The endless limp and pompous official speeches will begin around 6:30pm. The presence of high society types is expected. In particular, the immortal Ragnar Kjartansson, the great grandson of Zurich artist Fabian Marti, the many successors and heirs of the sculptor Dafino, the cryogen-frozen remains of actor Ryan Gosling, Gany-mede’s smart fungus Lord Runing Clam, and most of all Klaus’ nice round butt cheeks are all awaited at the start of the evening in the Pinacoteca’s stucco-decorated buffet hall.

-Renaud Loda, 2019

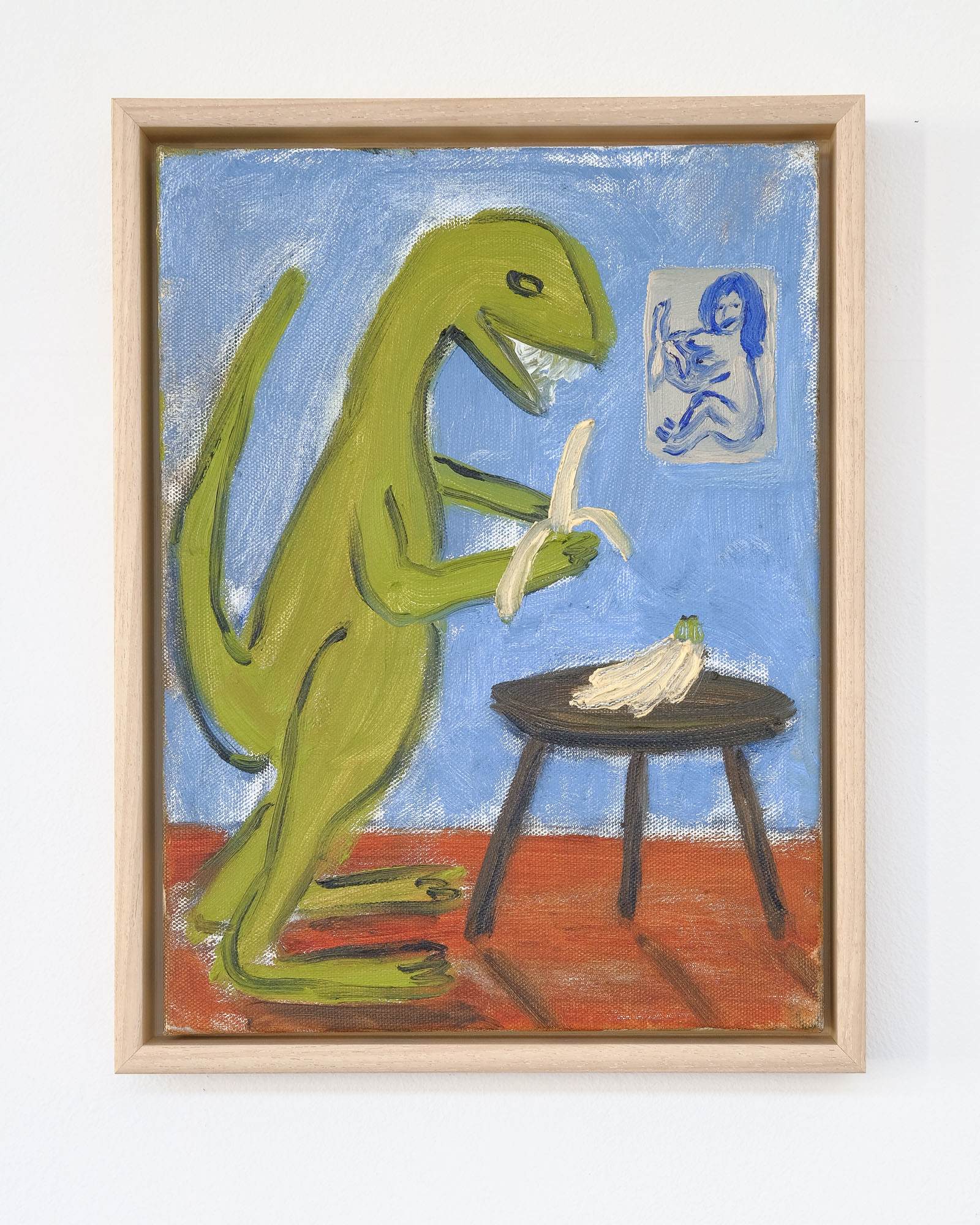

I can’t forget the first time I saw a painting by Keith Boadwee and Club Paint. A poodle tears a pain-ting with its docile, useless jaws, its fur a kinetic, frenetic set of scribbled lines. The painting is called French Revolution. It is a funny painting, full of permission and delight. But it also keyed me into a fact of Boadwee’s painting that is not a joke. French Revolution, like many of Boadwee and Club Paint’s works, takes the piss out of Painting writ large, but its grammar is derived from that same tradition. It is at once a study and commentary on the history of painting, and an utterly new take on what the medium can be and do. His approach includes both deep irreverence and the permission which is-sues therefrom, and an almost deranged devotion to craft.

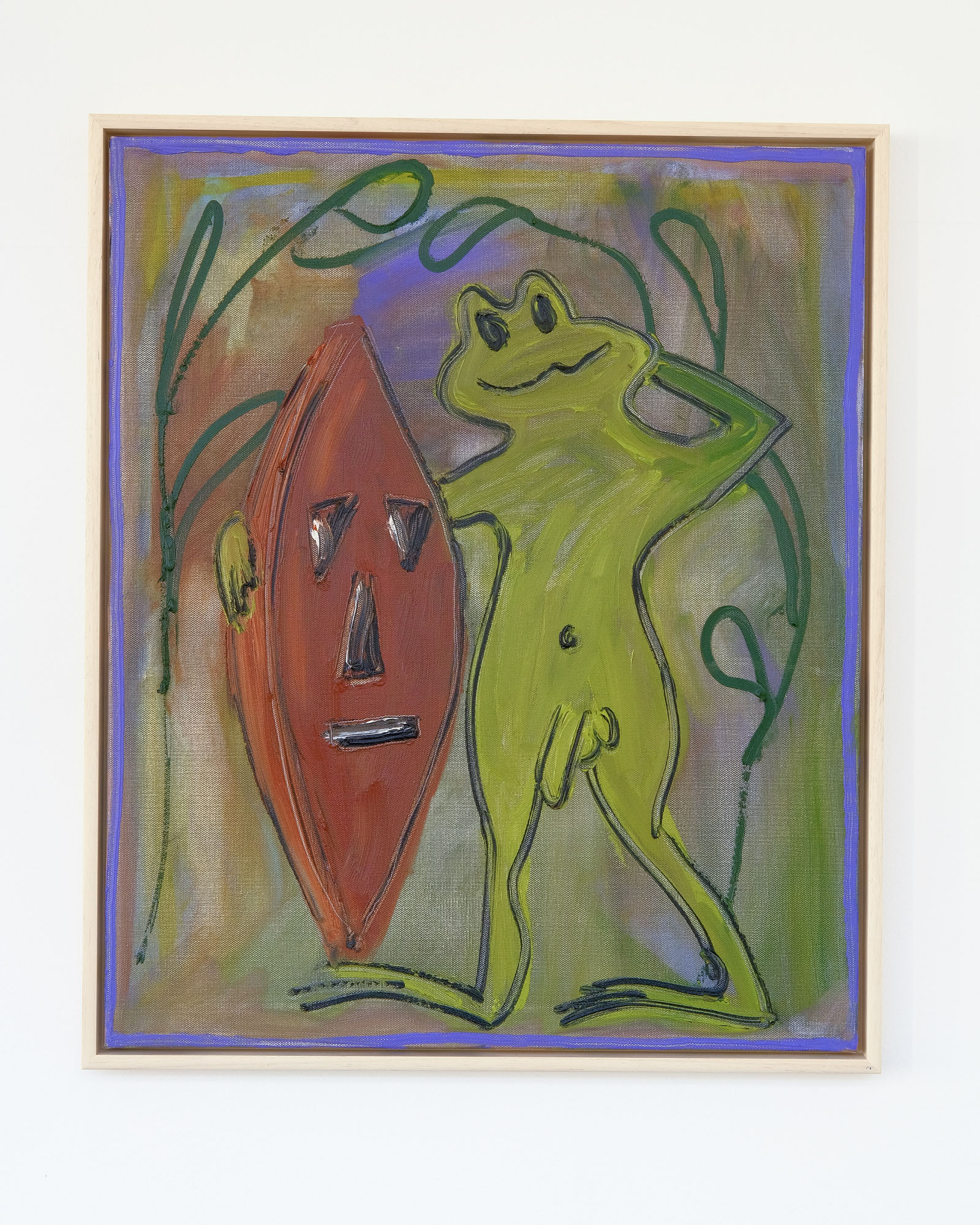

This attitude, in Boadwee’s hands, is tremendously productive. He manages to return to the same imagery and themes over and over and yet each picture feels like a surprise. An incomplete list of what you’ll regard in this book: a cock pissing into the open mouth of a fish in a bowl, several water creatures smoking cigarettes, a person shitting into an open piano, a prancing toilet, a whole cor-nucopia of turds, cocks, animals and fruit. What connects them, for me, is a dual sense of liberation and loneliness. I’m referring to the immense, unforbidden pleasure of looking at a crab at the bottom of the sea floor, huffing plumes of smoke from a cigarette; a horse fisting another horse; a human figure fucked from behind by a big bird. These paintings are shameless, both in their candor and in how they court our affinity. But these works are, at the same time, full of pathos.

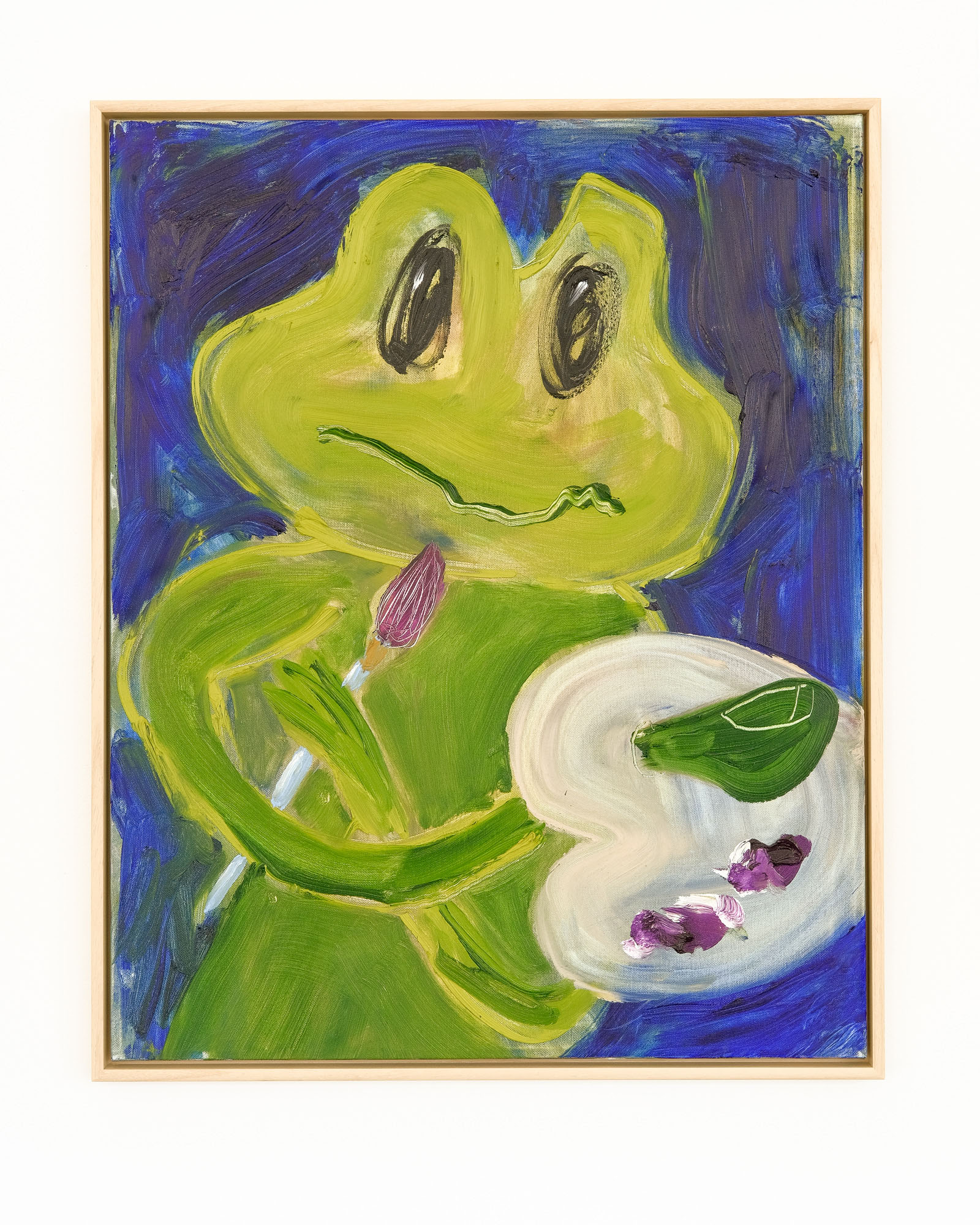

Country Sad Palette Man links the practice of painting with this pathos, showing a palette whose vivid globs of paint make the shape of a frowning face. It’s an abject image of the despair common to ambition, and yet its existence is a refusal to concede to a simple depression. Fish Smoking A Ciga-rette (Purple) portrays a fish swimming in a bowl against purple background, calmly smoking. I don’t want to project—smoking alone is one of the great pleasures of this hellworld. But it underscores the solitary life of the pet fish, whose pastures are, of necessity, oppressively narrow. If Boadwee’s work can’t simply love the history of painting, it suggests that painting can be one of the human activities that make life worth living. Like a good fuck, a laugh, a cigarette. Even sadness, as a strong feeling that proves we are alive to experience it.

These paintings are in some sense about the love of painting. A love, like all loves, that manifests in different forms, ranging from the desperate to the serious to the silly. In Happy at Huffin House, a smi-ling frog brandishes a palette, clearly caught in the middle of what is an activity of pleasure. Like how you stand around and look at painting and think about something as immense and meaningless as color. I warn against reading these paintings as allegories. Of course, as a communist drama queen, I want to read Old Glory, in which a naked figure extends hips and legs to the air with an American flag in his ass, as a condemnation of our country’s wicked dominion. Maybe? But in Boadwee’s paintings, almost anything can go into an ass. A frog’s fingers, a horse’s hoof, a nicely-shaped banana.

The body’s holes are full of meaning. What goes in and what empties from within are at once the zones of our greatest pleasure and our most disturbing products. That’s the world, I mean. Keith Boadwee’s sensibility is expansive: witty and courageous, gross and sublime. Like the world, it contains a catalogue of delights and nightmares. It’s a world made better, more livable, more itself, by the fact of these extraordinary paintings.

-Brandon Brown, 2019