Artist: Yuri Pattison

Exhibition title: the engine

Venue: The Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin, Ireland

Date: December 16, 2020 – July 31, 2021

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and The Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin

The Douglas Hyde Gallery is delighted to present a solo exhibition by Yuri Pattison, whose work in the last 10 years has addressed the impact of digital technology on both infrastructure and everyday life. Utilising video, sculpture, and online platforms it explores the political, material and social consequences of the rapid development of technology. His works move across platforms and materialities, connecting off- and on- line spaces. Having exhibited extensively internationally at an early stage in his career, this will be Pattison’s first solo exhibition in a major institution in Ireland.

In time.

The engine is a metaphor that surrounds us, as present in the bodies of airplanes and cars as in the search engines used to access information, to the relentless grind of the systems of capital, the realities generated by these forces, and the possibility of the emergence of new realities when these systems fail. ‘the engine’ exposes the connections between how the virtual world informs material reality, the ways in which ideas formally explored through acts of simulation and modelling in gaming – the exhibition’s title alludes to ‘game engines’ which create the internal architecture of video games – are also applied to real world circumstances.

The exhibition comprises a series of newly commissioned artworks in an altering and immersive installation that spans across the two levels of Gallery 1. At the centre is sun_set pro_vision (2020-2021), an ongoing work which generates a sun simulation against an abstracted seascape in real time presented across five large video wall screens positioned on dexion (i) support structures. The central screen is a top down view of the ocean, while the four surrounding screens present views from the angles “true” north, south, east, and west. The sun simulation recalls the multiple associations of sunsets and sunrises across histories- from longstanding pagan or religious rituals, to the dawning of a new age, often heralded in marketing campaigns. The seascape is illuminated by an accelerated version that matches the sun’s movement in Dublin.

The image on each screen is rendered live by a game engine, with variations of every aspect- colours, waves, movement and atmospheric thickness – influenced by data fed from an environmental air quality monitor, called the uRADMonitor. (ii) This altering seascape is a modelled reality; mirroring, abstracting and heightening unseen aspects of the physical world. The greater the volume of carbon dioxide, micro-particles, radiation and other pollutants recorded within the uRADMonitor, the more spectacular a scene is rendered. The everchanging rich violets and piercing yellows that can be displayed at any given moment recall the mesmerising and multi-instagrammed sunsets seen in heavily polluted metropolises around the world in recent years; the “beauty” of how polluted our world is becoming and how the infatuation with the new creates a collective blindness. Significantly, the title of the work, ‘sun_set pro_vision ’ refers to a known legal clause that specifies a particular law will cease to have effect on a specific date. ‘Sunsetting’ is a term often used in professional technology circles when a feature or website is phased out in software lifecycles. Both of these denominations lead us to envisage time as being ‘up’, and, in turn, towards the unsustainability of our modern world.

Within ‘the engine’ there is an echo from the recent past, Dublin’s ill-fated Millennium Clock – also known as ‘the time in the slime.’ Placed in the River Liffey in March 1996 to count down the seconds to the millennium, it was removed due to technical difficulties just 5 months later. Here the Millennium Clock is resurrected in Dublin Mean Time (2020), now counting up in seconds from 1st January 2000. The title of the sculpture recalls a more distant past, the 36 years (1880 – 1916) of local Coordinated Universal Time (successor to GMT) offset for Dublin during the early days of Standardisation. This historical measure serves as a counterpoint to the futility of the Millennium Clock, counting down its own irrelevance and representing the hopes and fears at the close of the 20th century.

Throughout the galleries a series of LED lights dim and illuminate over a period of time. It’s always golden hour somewhere (2016 – 2021) is an ongoing light installation that utilises modified colour adjustable panels programmed to simulate the ‘golden hour’ light known to photographers and cinematographers to produce a particularly photogenic version of reality.

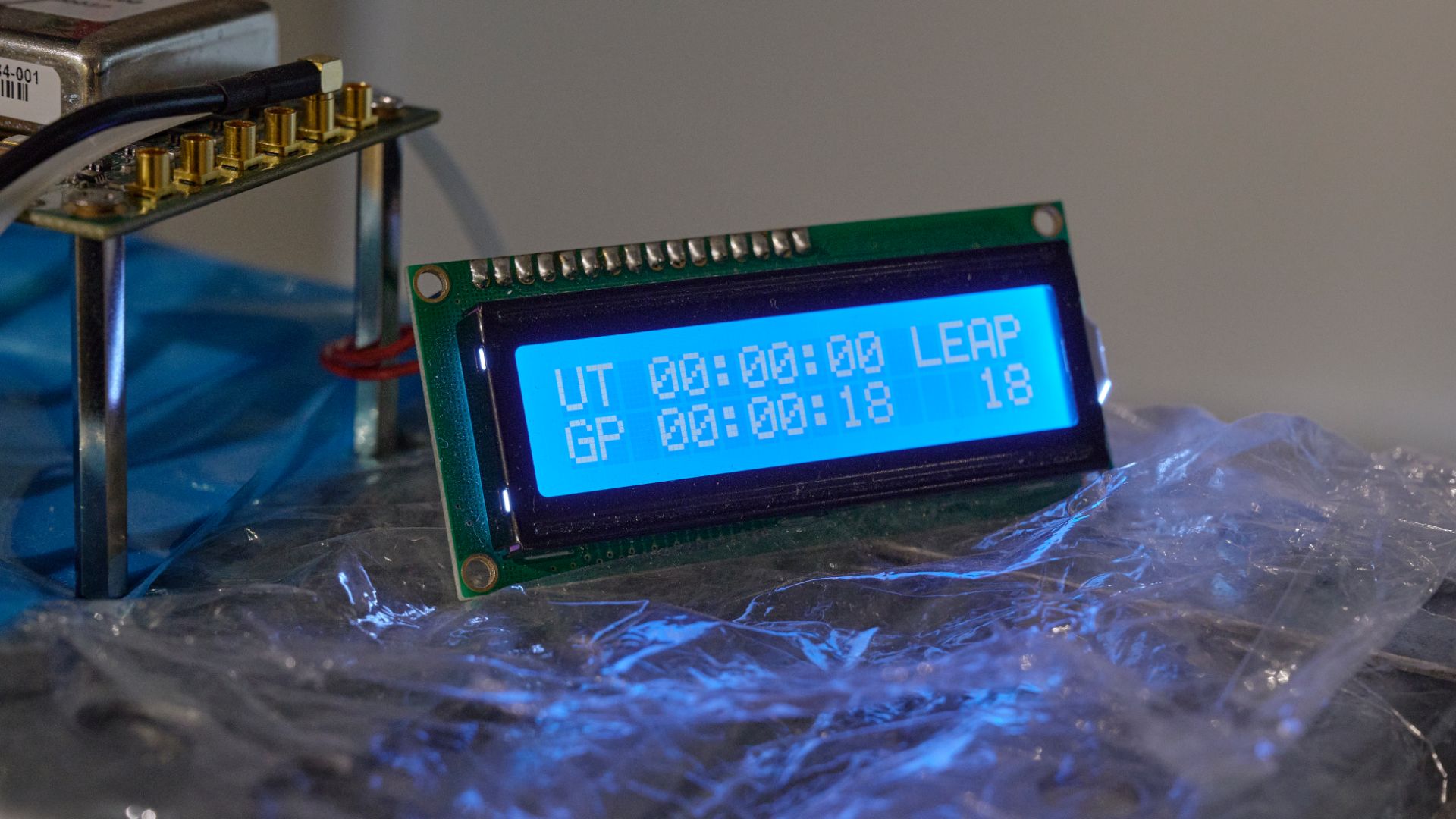

The beat pulsating from the sonic sculpture True Time Master (2019-2020) through the whole of the exhibition is from the Chip Scale Atomic Clock (CSAC). The CSAC is a miniaturised realisation of the highly accurate atomic clock that was developed by the US Defense Department’s infamous DARPA (Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency) for use in satellites, military drones, shipping, data centres and for telecommunication. This precise global time is the standard that controls our modern life, from digital computing and communications to financial activities that are faster than the operation of human consciousness. It is a clock without a face or a sound. Using the clock’s frequency, Pattison has worked with a former technician from the Royal Observatory Museums in Greenwich to make it audible through a Chinese counterfeit McIntosh MC275. The MC275 is an amplifier synonymous with US technological and cultural power in the 1960s; its uncanny reproduction evokes the current anxieties surrounding Chinese geopolitical dominance and technology (for example, 5G). (iii) These newly translated sounds are further amplified throughout the gallery by a series of PIR insulation panels. These are fitted with transducers also acting as visual ‘bounceboards’ to reflect the shimmering colours of the sunset.

The clocks in these two works Dublin Mean Time (2020) and True Time Master (2019-2020) exist in different tenses. While the Millennium Clock referenced in the former was the digitisation of a countdown clock as a projection of the past into the future, the CSAC only exists in the present. Its now audible beat exposes the idea of “true” time passing, and with it the computer and the internet as the new engines driving this forward. True Time Master (2019-2020) makes perceptible the links between global navigation, military conquest, extraction of natural resources, finance and trade. The CSAC is a direct descendant of the ships’ clock which drove the first wave of European conquest, True Time Master (2019-2020) is an exercise in exposing the colonial ties of everyday time-keeping.

In the complementary work Chip Scale Atomic Clock promotional video (NVIDIA Super SloMo + waifu2x rework) (2020), the promo video for the CSAC is slowed down echoing a recent viral trend in which songs are slowed down by 800% to 24 hours. Using machine learning software to predictively create and interpolate new video frames from the video’s existing timeline. The action points to the possibilities of alterations in perceptions of time – and history – through the proliferance of artificial intelligent technologies.

This newly commissioned body of work considers our shifting relationship with time; how networked technology has re-orientated our sense of it, and, in turn, changed our perceptions of reality. Its resonance is all the more acute with the events of the last year, where time has been reshaped on a mass scale, and words like “blursday” (referenced in the work of the same name positioned at the entrance of the gallery) are coined to describe the phenomenon of perception of days folding into one another.

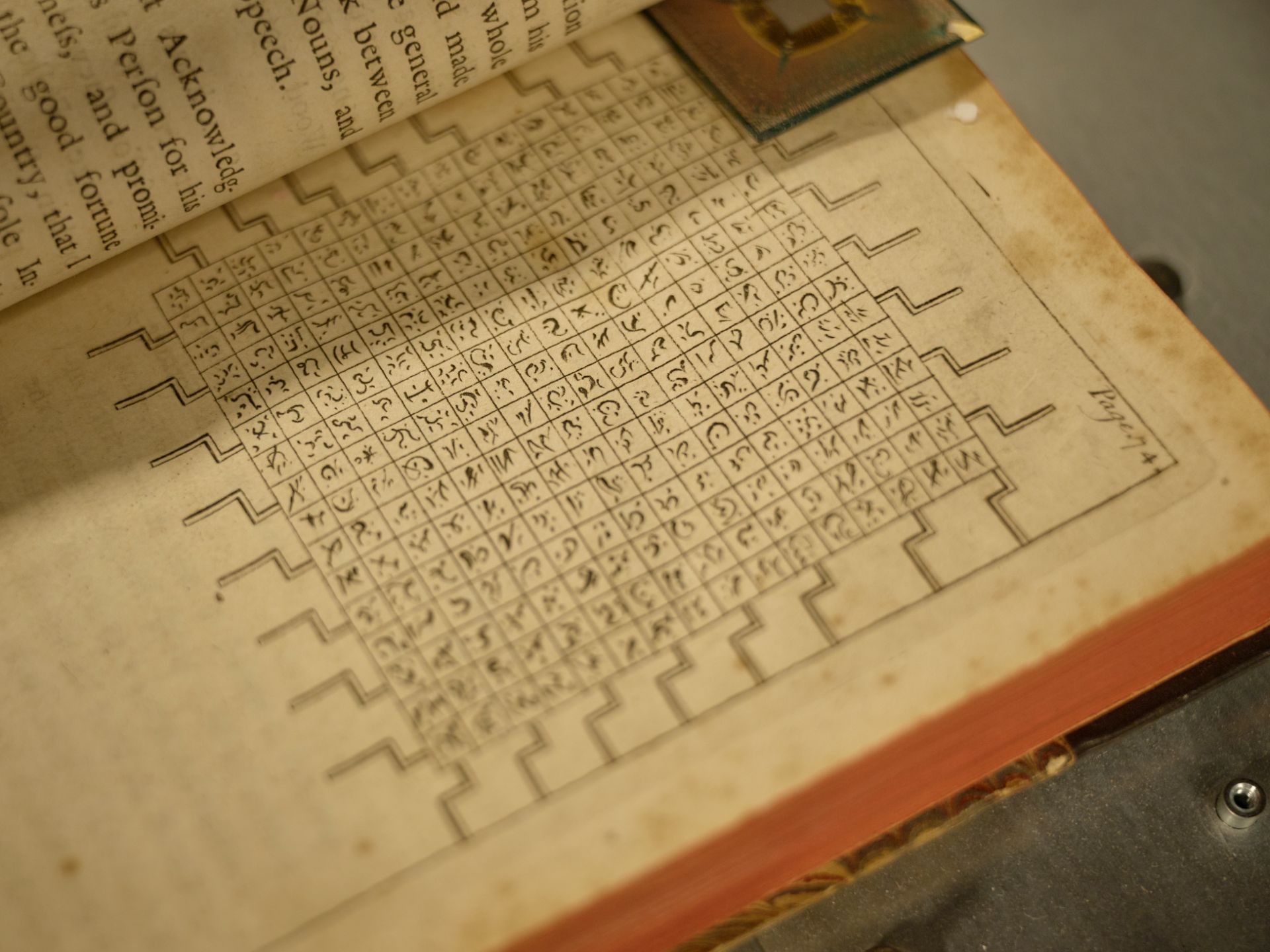

A final allusion to note in the exhibition’s title is ‘The Engine’ as depicted in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726), possibly the earliest description of a computer-like device in literature. This ‘Engine’ appears within a chapter that describes a technology obsessed society who’s misplaced endeavours have not led to any improvement to the lives of its ordinary citizens. This connection provides a reminder that artificial intelligence is inescapably predicated on human intelligence, a reminder that those modelling the future create the realities that we live in. We build the engine as it builds us.

(i) Dexion, a lightweight, easily transported material that was developed in the middle of the 20th century in Britain. Dexion became a protagonist in narratives of British soft power deployment during its early years, particularly as a means

of facilitating disaster relief. Pattison’s use of the material is inscribed with a technological melancholia; yesterday’s technologies of tomorrow have fallen into a present day abeyance, rendered all but obsolete by discourses of austerity and capital generation that sneers at the (paternalistic) idealism of the Post-War zenith of Keynesian welfare-capitalism.

(ii) It is part of a networked system developed to independently monitor environmental conditions and air pollution initiated against the backdrop of multiple disastrous environmental cover-ups and rising climate change denial. Over 300 units monitor conditions across the globe outside of official information channels feeding the date into a live map. Values of openness and accessibility pervade in a real- time presentation of environmental conditions for everyone to see.

(iii) These counterfeits (of normally US manufactured amplifiers, once accessible but now considered luxury items that appeal to American baby boomer generation’s nostalgia) are aimed at the middle class Chinese domestic market.

Yuri Pattison (born Dublin) lives and works in London. Recent solo exhibitions include “to-do, doing, d̶o̶n̶e̶”, mother’s tankstation limitded, London (2019), “Trusted Traveller,” KunstHalle St. Gallen (2017), “sunset provision”, mother’s tankstation limited, Dublin (2016-17), “user, space”, Chisenhale Gallery, London (2016), “Architectures of Credibility”, Helga Maria Klosterfelde Edition, Berlin (2015) and “Free Traveller”, Cell Projects, London (2014). Pattison is the recent recipient of the Frieze Artist Award 2016.