Traces of everyday experiences over the course of a year, memories of school days, deceased friends or family members, or traces of aging on the skin: in her exhibition, Spuren (Traces), Yoriko Seto brings together works in which she interweaves everyday experiences with memories through her drawings, reflecting on her family, her upbringing in Japan, and her growing older in Germany. These traces come together to form a mosaic of experiences, memories, and reflections on life and its passing.

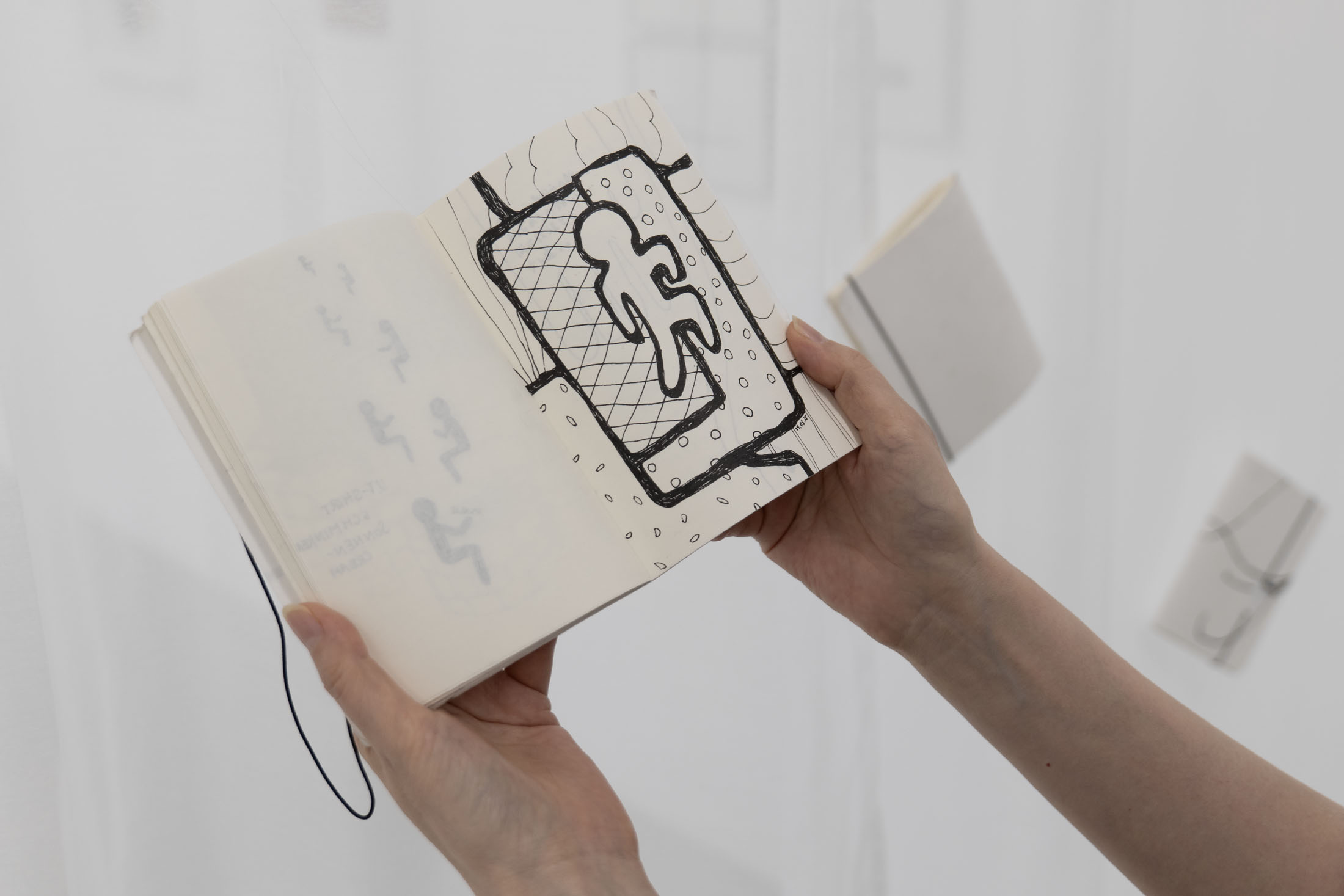

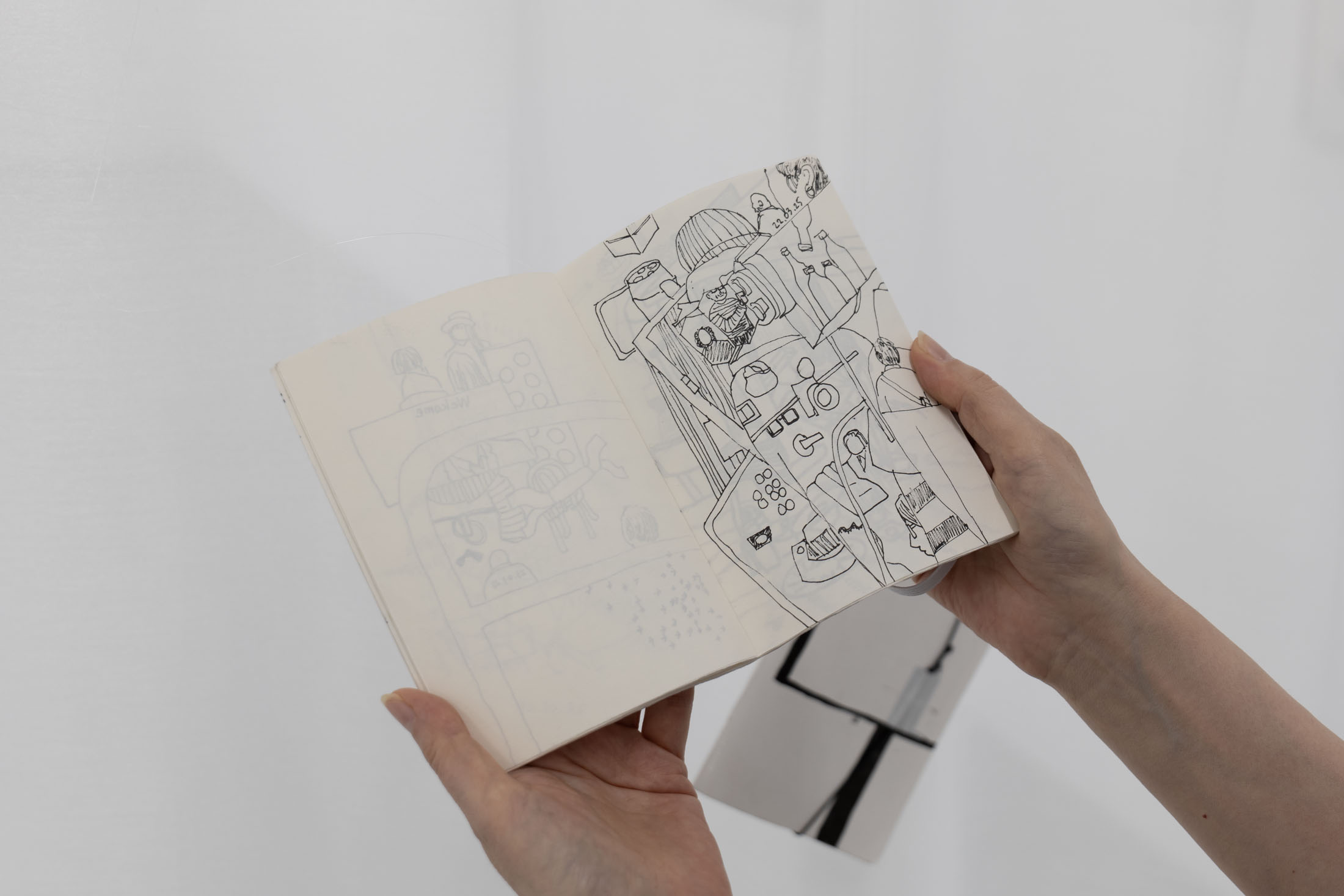

Drawing forms the basis of Seto’s artistic practice. Since 2017, she has been keeping regular drawing diaries to record her personal experiences. By capturing seemingly mundane things such as casual scenes, thoughts, and observations in her drawings, Seto quietly resists forgetting. In Spuren, she presents last year’s drawing diaries. The originals hang on thin threads in the room and can be leafed through. In addition, reproductions of the drawings can be purchased in an artist’s book compiled for the exhibition during the artist talk on 1 February 2026. Seto uses this practice of compiling, sorting, and reproducing as a form of reflection on the past year. For her, the drawings in the sketchbooks are also a kind of unit of measurement for (passing) time. Publishing them in turn offers the artist the opportunity to share her time with others.

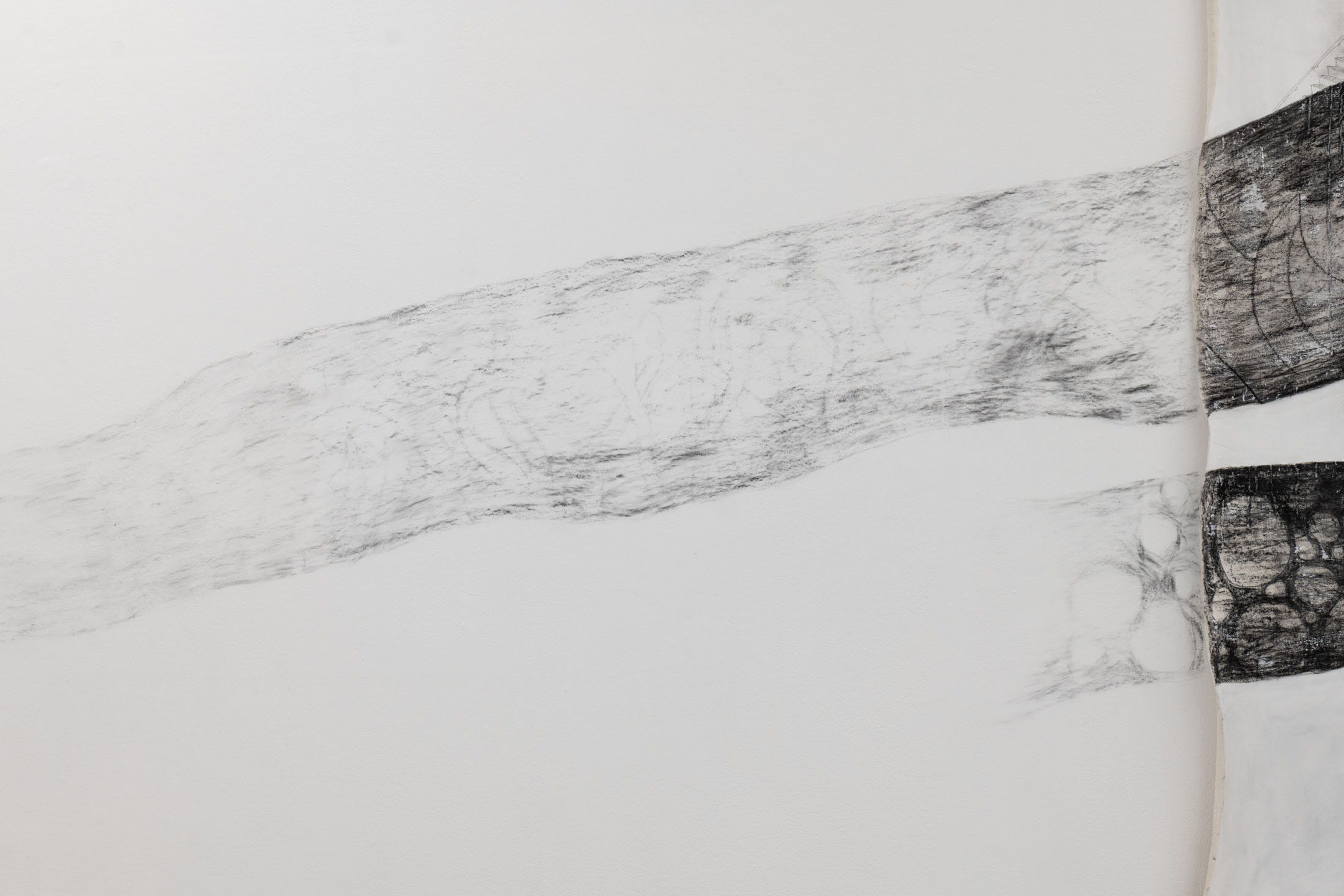

Seto not only draws her current thoughts and experiences, but also uses drawing as a form of remembrance: initially abstract lines give rise to fragments of memories of her friend and aunt, who passed away last year. Seto weaves these fragments of memory into meter-long charcoal drawings in a creative process lasting several months. Seto is just as interested in the traces of memory as she is in the traces of charcoal on the drawing surface.

The drawing Du brauchst nicht zu antworten (You Don’t Need to Answer) (2025) shows large, branch-like structures that cross the piece of fabric serving as the ground several times and extend beyond its edges onto the wall. Playfully drawn feet, kidneys, and contact lenses can be made out in the branch-like structures. Between them are further small drawings of everyday moments over blurred, illegible lines of Japanese text. These lines of text are excerpts from texts written between the artist and her recently deceased aunt.

Seto weaves these fragments of memory into a tribute to her aunt. Similar to memories, the elements remain partly shadowy, partly abstract, overlapping and refusing to be clearly defined.

The drawing nacheinander (one after the other) (2025), which is over seven meters long, also presents various symbols, some abstract, some concrete: branch-like structures, paths, open doors or windows, geometric shapes and surfaces, abstract shapes and lines reminiscent of hair, a large cup, and several drawings of feet and legs – as seen in the work Du brauchst nicht zu antworten. (2025). Here, Seto interweaves her memories of visiting her friend in the hospital before she died with her memories of her aunt. What images emerge as memories when a person has passed away? Drawing becomes a process of remembering. Below the drawing Du brauchst nicht zu antworten. (2025) and at the bottom edge of the drawing nacheinander (2025), a narrow border of charcoal dust accumulates as a trace of the creative process. Just as not every impression returns clearly in the process of remembering, the charcoal trickles uncontrollably onto or next to the drawing surface. It leaves vague traces that can no longer be traced back completely.

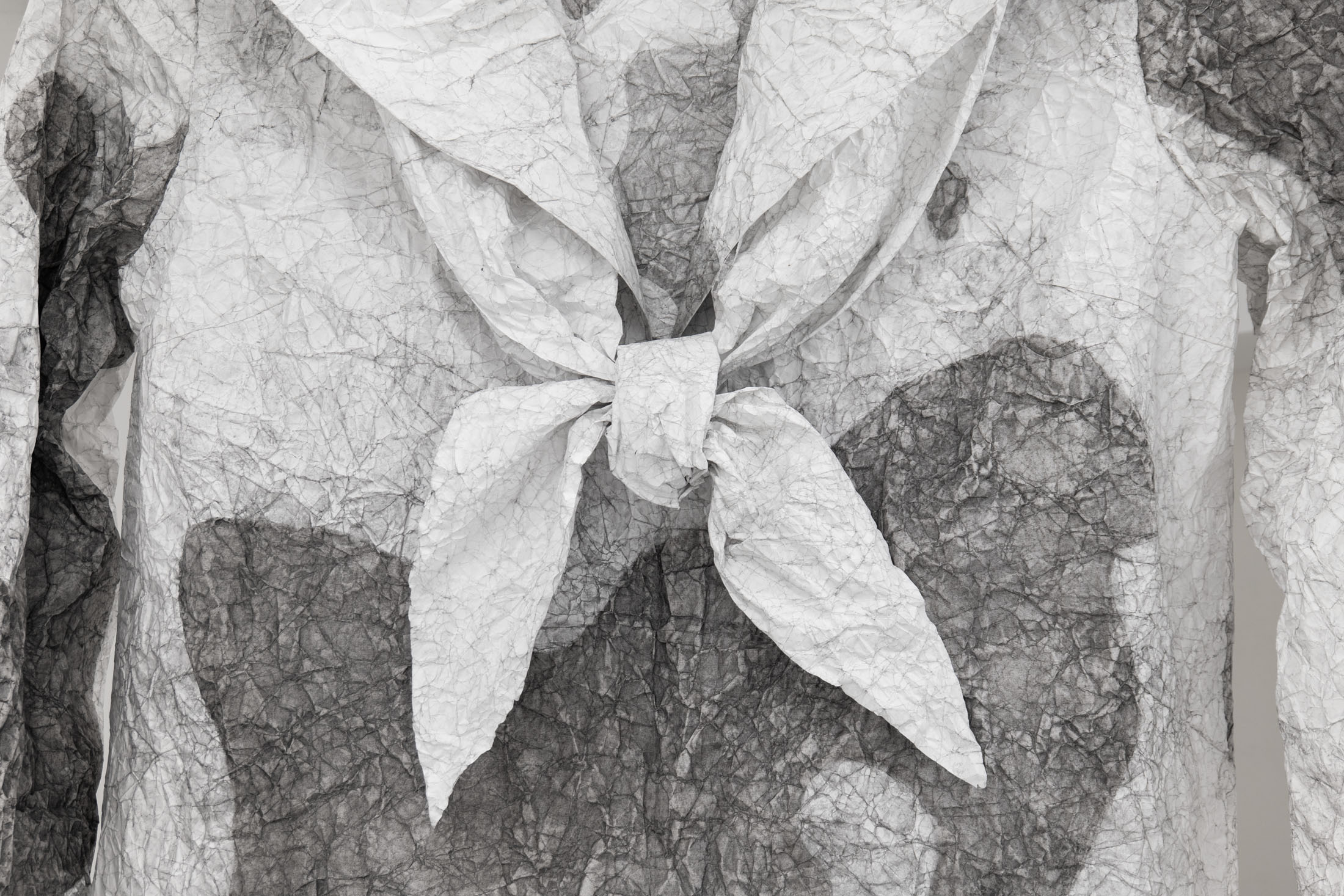

The installation, uni (2025) – an oversized Japanese school uniform (seifuku) made of paper onto the back of which an animated film is projected – also arose from the combination of traces of memory and everyday observations. In this large-format installation, Seto works with memories of her school uniform, which she wore as a young girl in Japan, and adds her reflections on growing older. In Japan, seifuku are based on the design of military and naval uniforms from the Meiji era, making it immediately apparent which school the students belong to. At the same time, they create uniformity within the group, concealing social differences and individuality. Seto connects these demands for uniformity with social beauty standards, such as flawless skin without wrinkles or age spots, which she encounters in the process of growing older. To create the paper seifuku, Seto transferred pigment spots from her skin and that of her friends onto large-format paper. The artist enlarged the skin spots, which were actually only a few millimeters in size, to almost one meter in her drawings. She then crumpled up these drawings and tried to smudge the spots away by rubbing the paper together, similar to how she and her friends treat the spots on their skin with bleaching creams and lasers. The seifuku made by Seto defies the demand for uniformity with its folds and stains. She gives the uniform, a symbol of uniformity, an individual character.

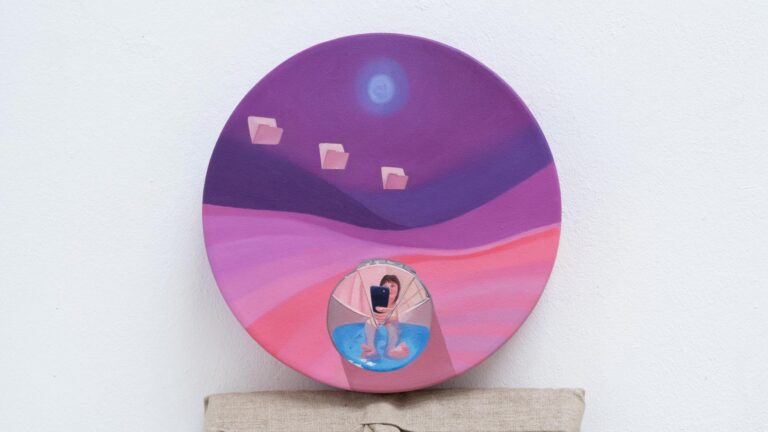

Seto transferred this examination of social beauty standards and questions of social conformity and belonging into an animated film. In a group of identically drawn figures, a single one is given a pattern of dark spots of descending particles. This figure is taken out, its spots are removed, and it is reintegrated. But the falling flakes give her a new pattern – an endless cycle of conformity and the blossoming of the extraordinary.