Artist: Won Cha

Exhibition title: then wear, does our mind go?

Venue: LC Queisser, Tbilisi, Georgia

Date: April 8 – May 30, 2021

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and LC Queisser

LC Queisser is pleased to present then wear, does our mind go?, a solo exhibition of new works by Philadelphia-based artist Won Cha. This is Cha’s second solo exhibition at the gallery.

Cha describes his works as simultaneously existing within and constituting a “site.” Like the symbols collected from various cities, spaces, and archives that appear and transform across Cha’s installations, the artist’s sites are protean. There is a sense that the site has been constructed and deconstructed time and again that the site has traveled, picking up traces along the way that change the shape and texture of each incarnation.

In South Korea in the 1960s-1980s, a form of underground activist theatre called madangguk grew alongside the democratic Minjung movement, organized by and for mass society in resistance to a violent, oppressive and corrupt military government that was supported by the American occupying force. The madangguk were informal political theatre performances conducted during a time when any form of public protest was strictly prohibited. The locations of the performances changed regularly, and the performers were all amateurs, coming from the communities that these plays addressed. One example of a madangguk began with a celebration of traditional farming life and culture, followed by an enactment of the economic hardship farmers were facing. In the third part, the performers created three characters to embody oppressive forces that were at the root of this hardship. The first was dictatorship, played by a figure in an army officer’s uniform. The second was monopoly capital, played by the character of a wealthy businessman. And the third, called USA was the character of imperialism, white supremacy, militarism and exploitative multinational corporations. The three forces became frenzied and ecstatic, dancing with one another in an erratic intoxication. The performance culminated with the appearance of a shaman, also played by a community member. She would enter into a trance state in order to exorcise the three evil spirits. Performance studies scholar Eugene van Erven writes of this fourth act, “the shaman shouts in the middle of all this ecstasy: ‘We won’t pay rent! Stop the foreign imports! Let’s unite our divided country! Free the political prisoners!’ The audience gets up and follows the shaman, dancing behind her and repeating her words in chorus.” (1). These performances addressed a silenced immediate experience of desperation and oppression inside the space of the room, in the bodies of the actors and the audience. In this cathartic embodiment and release, energy spilled out from the theatre, unstoppable, onto the streets.

Cha’s practice, his relationship to the site, connects to the tradition of the madangguk. Inside the exhibition space, a psychic energy coalesces into physical form. Prior to this address, it had existed as a constant shrill hum, a repressed, indefinite swarm. In giving the swarm a shape, there is the opening for release, for action, for protection, for a powerful overflow.

The site at times exists in the space of the exhibition and at other moments in the space of the work itself. In his video work Dear Don, 2021, Cha delineates the space of a couple living in Philadelphia following the murder of Walter Wallace Jr. by police in October 2020. Pink-purple text comprising a letter from the artist to his partner is laid atop a collage of moving images. Video footage shot by Cha on a cell phone through an apartment window of police, lights flashing, approaching a car, as loud helicopter-like sounds overwhelm, sits next to two hands, holding and stroking one another with love. Two sharp still images are paired, one showing a hospital visitor ID and a polaroid of the partner, and another N95 masks for sale on the street. We see footage of fireworks exploding in the night sky. Next, there are still images of the interior of a bedroom, two pairs of shoes on the floor sitting alongside footage taken from the sidewalk of the ultra-bright lights police use to flood the street at night.

In the site of this film, as happens elsewhere in Cha’s work, the personal and the familial become deeply intertwined with the historical, the archival, and the political. Lines draw outwards from specific experiences to connect to historical events, figures, structural conditions, methods for survival, sources of joy to create a dense web full of nodes rich in intersecting complexity. The text of the letter contains these nodes. It describes the specific challenges the couple faces as the state actively neglects the healthcare needs of the partner’s father after suffering long-term effects from COVID-19. This then leads us to the nervous systems of the couple and a sense that a finite resource, something that keeps us alive, is being depleted. We as viewers connect the conditions of the past year, the COVID-19 pandemic, the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on communities of color, along with the uprisings across the US for the Black Lives Matter movement and the violent backlash from police and military forces, to what Cha refers to in describing the space the couple exists within. But far past the events of 2020, Cha draws a line to his childhood, watching his mother live within conditions in which she had to extend herself far beyond her limits in order to survive. The depletion the letter discusses, the effects of pushing past one’s limits, the effects of living within conditions in which survival is intransigently threatened, clearly transcend recent history. There is a sense again of the traveling of a disembodied swarm across time. The site of the film becomes a body that holds the space of the couple through an assault, it becomes an insulation around the bedroom, a deepening of the well of this precious, drained resource.

Next to the film on the floor is a small altar painted in red, blue, green, white, yellow and black, a color scheme that appears across the exhibition and that is entwined with traditional Korean shamanistic practice. On the wall hangs a shaman’s shirt, painted in the same colors as the altar. Long strips of a painted American flag hanging from the sleeves. Shamans would use these specific colors to evoke chaos and liberation when exorcising oppressive forces. Cha’s partner’s hoodie is collaged into the body of the garment. With the zipper undone, we see Eldridge Cleaver’s visage collaged into a traditional Korean shamanistic drawing of a god. These shamanistic deities have always changed over time, evolving and transforming to meet current needs and conditions. These drawings are not seen as depictions of the gods but as incarnations, existing as the god themselves.

The film concludes with footage of fireworks reversed, imploding into a center, beginning bright and disappearing into a core. The text over top reads, “my mom would say / jjung sheen/ up suh/ alot/ that/ means/ out/ of/ mind/ but where/ does the mind go?” As the shaman in the madangguk cut through to another world in order to exorcise the demons of dictatorship, monopoly capital, and imperialism, there is a sense in the room that a similar cutting is taking place. This time, not to exorcise but instead to find and reclaim, to find and fortify the lost mind. This search is an act of love, as the protection the film offers the couple is also an act of love.

With each assembly, disassembly, and reassembly of a site, new forms, colors, characters, gods, symbols, nodes are created. They join a living vocabulary that Cha’s artistic practice continually draws upon as material for protection, for exorcism, for visiting, for fortifying, for survival, for love, for construction.

– Marina Caron

[1] Van Erven, Eugène. “Resistance Theatre in South Korea: Above and Underground,” TDR (1988-), Vol. 32, No. 3, MIT Press, Autumn, 1988, pp. 156 – 173.

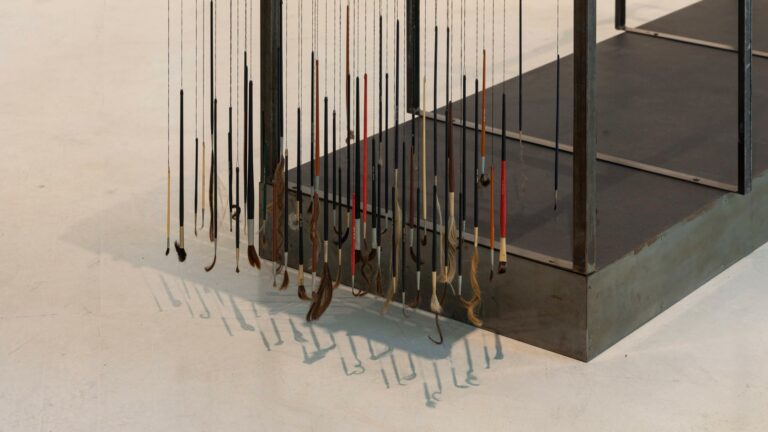

Won Cha, then wear, does our mind go?, 2021, exhibition view, LC Queisser, Tbilisi

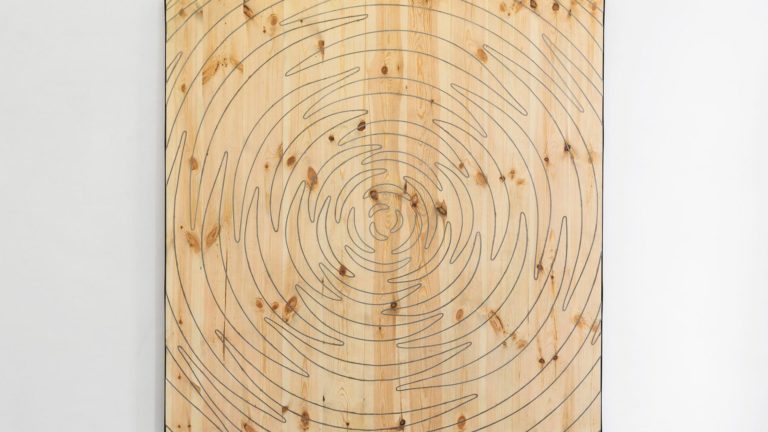

Won Cha, Offering, 2021, Wood, plastic, paper, paint, print, cloth, rubber, nails, 246 x 244 x 13 cm

Won Cha, Offering, 2021, Wood, plastic, paper, paint, print, cloth, rubber, nails, 246 x 244 x 13 cm

Won Cha, Offering, 2021, Wood, plastic, paper, paint, print, cloth, rubber, nails, 246 x 244 x 13 cm

Won Cha, Offering, 2021, Wood, plastic, paper, paint, print, cloth, rubber, nails, 246 x 244 x 13 cm

Won Cha, then wear, does our mind go?, 2021, exhibition view, LC Queisser, Tbilisi

Won Cha, then wear, does our mind go?, 2021, exhibition view, LC Queisser, Tbilisi

Won Cha, where do you start and I begin, 2021, Mixed Media, 80 x 43 x 20 cm

Won Cha, then wear, does our mind go?, 2021, exhibition view, LC Queisser, Tbilisi

Won Cha, then wear, does our mind go?, 2021, exhibition view, LC Queisser, Tbilisi

Won Cha, Gate of souls, 2021, Wood, metal, chain, plastic, paper, paint, lightbulbs, 264 x235 x 80 cm

Won Cha, then wear, does our mind go?, 2021, exhibition view, LC Queisser, Tbilisi

Won Cha, then wear, does our mind go?, 2021, exhibition view, LC Queisser, Tbilisi

Won Cha, Eshmaki, 2021, Ink on cloth, plastic, 86 x 83 cm

Won Cha, then wear, does our mind go?, 2021, exhibition view, LC Queisser, Tbilisi

Won Cha, then wear, does our mind go?, 2021, exhibition view, LC Queisser, Tbilisi

Won Cha, Quitschi, 2021, Acrylic on cloth, 189 x 167 cm

Won Cha, Quitschi, 2021, Acrylic on cloth, 189 x 167 cm

Won Cha, Fold your cloth, 2021, Cloth and acrylic on plastic, 26 x 78 x 57 cm

Won Cha, Dear Don, 2021, Digital video file, 394 secs

Won Cha, Dear Don, 2021, Digital video file, 394 secs